The Kid Gets Out of the Picture at the GSD

The vocabulary of early nineteenth-century picturesque landscape architecture is almost entirely alien to contemporary ears. Clumps, lumps, masses, groups, belts, hollows—these are a few of a vast catalog of objects that once belonged to design and have long since been absorbed into colloquial ubiquity. While the disciplinary meaning of these terms requires historical recovery, the project around which they were organized is entirely familiar. In the simplest terms, the picturesque was intent on reforming the real material of landscape and buildings to operate “in the manner of a picture.”

The ambition to make the world more picture—like, for all its intuitive simplicity, was actually a complex operation that required the invention not only of new ways to plan and design, but also new ways to theorize relationships between design and its audience. As an act of design, the picturesque used objects and techniques that would bring real material closer into line with the medium specificities of painting and drawing. Clumps, groups, and masses, for instance, can all be read as ways of clustering together trees and landforms so that they are more readily analogous to the way paint is applied to canvas.

The ambition to make the world more picture—like, for all its intuitive simplicity, was actually a complex operation that required the invention not only of new ways to plan and design, but also new ways to theorize relationships between design and its audience. As an act of design, the picturesque used objects and techniques that would bring real material closer into line with the medium specificities of painting and drawing. Clumps, groups, and masses, for instance, can all be read as ways of clustering together trees and landforms so that they are more readily analogous to the way paint is applied to canvas.

Design’s audience, too, was engaged through traditionally pictorial devices. Scripted paths and viewpoints separated scenery into foregrounds, middle grounds, and backgrounds like the depth of a picture plane. New discourses of visual consumption were developed to rationalize and describe the “tastes” of scenes with a high degree of precision.

“The Kid Gets out of the Picture”—with a nod toward Hollywood’s desire to “stay in the picture”—revisits the catalog of picturesque nouns with a different goal in mind. Is it possible to return the moment when the picture became the instrument for the reformation of design and re-emerge with something different? The purpose is not so much to bemoan the relationship between design and the culture of picture- or image-making; we take that as immutable and here to stay. The purpose is instead to simply work for a while in the opposite direction. Perhaps elements of the picture can find their way out into space. What spaces, organizations, and forms of life are possible in this catalog of nouns?

For this exhibition, we take clumps as our point of departure. In William Gilpin’s drawings of the late eighteenth century, clumps are dense, heterogeneous assemblies of trees, rocks, bushes, sometimes even sheep and clouds. A selection of these can be seen on the rear wall of the library. To navigate the drawings in a literal sense would mean walking through a field of things freely distributed in section. Being under, on top, or alongside, would happen simultaneously in an overflowing of prepositional relationships. “Things” here are important. Clumps are not just composed of some primordial base material, but agglomerations of identifiable, known “things” packed together in close association. Remarkably, despite all of the possible affiliations with categories of objects in contemporary art and architecture (the assembly of heterogeneous parts, the emphasis on known “things,” the atypically formed) clumps resist categorization. Clumps are not collages. Clumps are not intricate assemblies of continuously differentiated parts. Clumps are not difficult wholes. Clumps are not classical unities. Clumps are not socially didactic, teachable moments.

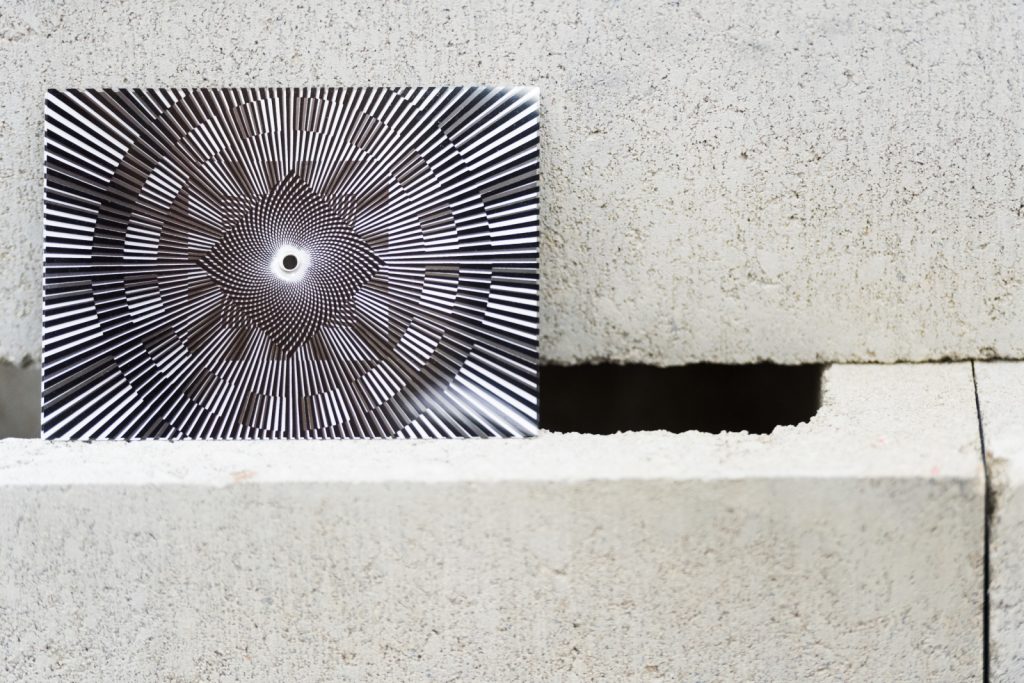

The clump in the center of the library gathers the work of four contemporary practices in a single agglomeration. It is a smaller version (a model, in a sense) of a sister installation currently on view at Materials & Applications in Los Angeles. The large plaster “blankets,” the piles of CMU, and the galvanized steel culverts are the work of The Los Angeles Design Group (LADG) and assistant professor Andrew Holder. The draped material here is reminiscent of recent digital experimentation in the modeling of landforms but is assembled together with elements of actual landform infrastructure like concrete block and storm water management devices. Jason Payne, associate professor at UCLA and principal of Hirsuta, supplied a version of the fake rocks common to picturesque landscapes. Here, the rock in question is actually of scale model of an actual asteroid called “Ida.” Andrew Atwood (GSD ’07 and assistant professor at UC Berkeley) and Anna Neimark (GSD ’07 and faculty at Sci-Arc), Principals of First Office, contributed a primitive Dolmen re-rendered as a stack of boxes. Andrew Kovacs (lecturer at UCLA) and Laurel Broughton (lecturer at USC) created benches integrated with trees and synthetic parts of trees.