Design agency—the creative representation of big ideas—lies at the heart of Joanne K. Cheung’s (MArch ’18) work. A degree candidate in the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Master in Architecture program and a Fellow at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, she believes that art and design have a special capacity to shape how people see, and thus understand, complex issues.

“The world contains so much information, but people can’t see what’s not directly in front of them,” Cheung says. “Designers have the unique ability to show people things that don’t exist yet—like sending postcards from the future.”

When a designer’s task is to represent things that don’t yet exist, technologies that enable direct, embodied experiences can be particularly exciting. Across her work as a designer and an artist, Cheung has paid particular attention to how technology shapes perception, and specifically how the tools people use to see influence what they understand to be true or possible.

Last fall, Cheung collaborated with a group of GSD students on a virtual reality installation, entitled “Beach,” in which visitors could experience Harvard landmarks in a post-climate-change world (“Visit Widener Beach!” read one poster, with the iconic Widener Library set behind an advancing tide).

“The disaster drama is a familiar Hollywood trope. I find that the way the media dramatize the apocalypse acts as a distancing mechanism, to make it feel like it’s not directly connected to us, like it’s outside of our world,” Cheung says. “It makes natural disasters feel like a choice. In ‘Beach,’ we didn’t use the post-apocalyptic narrative. Instead, we showed the negative-sum outcome of climate change in a positive light, as a sunny beachfront. We wanted people to see the future in the context of their familiar, everyday life. Climate change isn’t a movie you can walk in and walk out of. It’s a continuation of our present.”

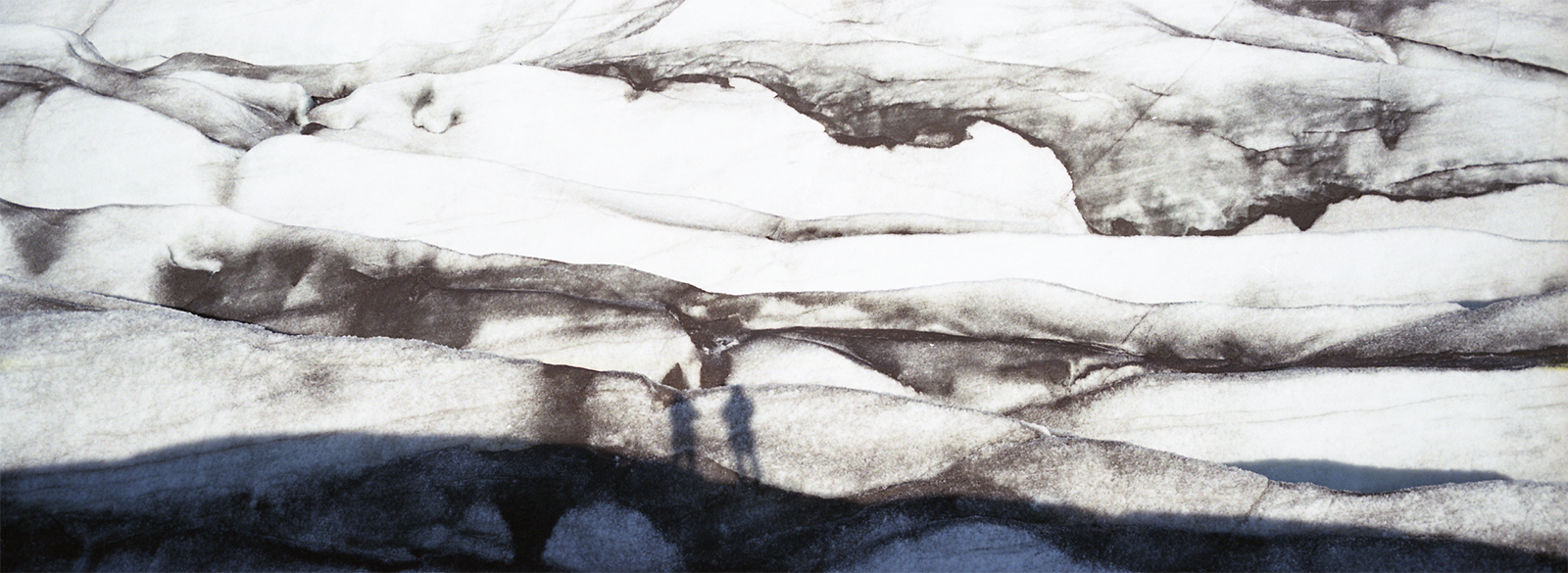

While visiting Iceland last summer—particularly, when confronted with the Svínafellsjökull glacier (a spur of the iconic Vatnajökull glacier, Europe’s largest)—Cheung faced a similar consideration: how might we represent the landscape in a way that would contextualize discourse around climate change? Is the first-person perspective enough for understanding a whole system, especially when that system is always changing?

“No single perspective can accurately represent something as complex as climate change. It’s a species-scale responsibility,” Cheung says. “We have to collectively take it on and represent it using tools from all of our disciplines, as scientists, policy-makers, activists, writers, artists, designers… We have to try everything.”

With these themes in mind, Cheung collaborated with researchers at the Iceland Glaciological Society, Icelandic Mountain Guides, and Harvard’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences to create a series of 360-videos of the Svínafellsjökull glacier.

Poetic representation is as important as scientific representation, Cheung feels—so while in Iceland, she traveled the coastline of the entire island nation and grew sensitive to its unique place, geographically and figuratively, within the climate change debate.

As an island nation, Cheung notes, Iceland has a landmass that is directly shaped by rising seas. This shifting seashore, in turn, changes the horizons one can view from the beach—literally changing how and what a person can see.

“I’ve always been fascinated by the fact that the horizon is an imagined separation and is highly subjective, depending on where you look from,” Cheung says. “Climate change directly shapes our perception of the horizon as the sea level changes the very contour of the island. For me, the horizon is also a metaphor for the limits of human perception. What we take to be the vanishing point is but the farthest point we can see.”

Experimenting further with poetry and perception, Cheung juxtaposed photographs of the horizon against poems by the Icelandic poet Stefán Hördur Grimsson. Cheung had been curious about Grimsson’s work for a while; despite not being able to read Icelandic, Cheung nevertheless felt emotional resonance from his texts, and sought ways to experience these poems visually if not textually.

In juxtaposing Grimsson’s poems against photos of the Icelandic landscape, Cheung found an avenue for the imagination—a way to “read” the land as we might read text. This approach—image as text as image—evokes Cheung’s first language, Chinese, in which characters are literally images.

Inversely, this staging pushes viewers to wonder, perhaps, what meaning they might be unable to grasp from an image, or what information or narratives are hidden therein.

“It drives a lot of my thinking behind landscape, because landscape is always text, is always landscape,” Cheung says. “And that relationship becomes really interesting when we consider the way computers perceive the world. What are the things that we take for granted when we look at a photograph? And what are the things the computer sees? What’s lost when we try to translate between human vision and computer vision?”

These observations from Cheung’s Iceland trip amounted to an art exhibition, entitled “Horizon,” and continue to inspire her current work on civic architecture and democratic participation.

“Recently I became enamored with a legal principle called ‘public trust doctrine’ that adds another layer to the metaphor of the horizon,” Cheung muses. “The principle holds that some resources in the world should always be held in trust for public use rather than private ownership.

“The seashore is an example of this type of resource: the space affected by the ebb and flow of the tides couldn’t be owned as private property because it’s already being used by the ocean. If we take the ocean as a metaphor for knowledge, then the seashore is where we come into contact with that knowledge. We have to be able to freely play in the waves.”

Or, as Cheung posed to the Harvard Gazette: “I’m a designer. It’s part of the job to think about the future.”

All images and video courtesy Joanne K. Cheung

Funding for Cheung’s Iceland project was provided by the Harvard Office for Sustainability’s Student Grant Program.

Project credits for “Beach”: Yaqing Cai, Joanne K. Cheung, Yujie Hong, Cindy Hu, Namju Lee, Jiabao Li, Jenny Shen, Jiho Song, Kally Wu