A Team of Harvard Researchers Develop a Prototype for a More Efficient and Eco-friendly Air Conditioner

Continuing a trend from this summer, September 2023 was the hottest September on record, according to scientists at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies. As climate change increases global temperatures, world cooling demands are expected to triple by 2050. While globally accessible and cheap to manufacture, conventional air conditioners still rely on wasteful mechanical vapor-compression methods and dated technology to cool and dehumidify air, making them one of the largest consumers of energy in industrialized countries. In response to these inefficient products and rising temperatures, an interdisciplinary team from Harvard is developing Vesma, a refrigerant-free, eco-friendly cooling solution suitable for all climates. In late August, their durable, low-cost, low-energy system was installed and tested in real-world conditions at HouseZero, headquarters for the Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities (CGBC).

Vesma combines two innovative systems with imposing names: cold Superhydrophobic Nano-Architecture Process (cSNAP) and vacuum membrane dehumidification, often called “DryScreen.” By using just water, this advanced evaporative cooling technology can pre-treat and dehumidify the input air, further maximizing its cooling capability and allowing it to be used in a wide variety of climate zones around the world. A version of the DryScreen prototype will be installed at Druker Design Gallery as part of the exhibition Our Artificial Nature: Design Research for an Era of Environmental Change, on display from November 13 to December 21, 2023.

Early testing showed that Vesma effectively cooled indoor air in extremely hot conditions and could one day replace traditional vapor-compression coolers with a much more sustainable option. Jonathan Grinham, Assistant Professor of Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), is one of the team leads working on Vesma. Grinham shared some test results with Joshua Machat, assistant director, communications and public affairs, at the GSD.

An interdisciplinary team from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Sciences (SEAS), Wyss Institute , and the GSD are behind the Vesma project. Could you explain the importance of this collaborative process?

The built environment and anthropogenic climate change are a deep causal loop. Designers need to untangle complex systems to re-think or even unlearn much of what we do, especially concerning a century-old way of conditioning interior environments. How we do this requires expertise across many fields. The GSD, Wyss, and SEAS faculty have cultivated a collaborative environment over the last decade or more. It has also had many different phases. Much of our early success came from translating problems. We found many interesting new technologies in the sciences looking for applications— solutions without the right problem. For example, the nanoscale barrier layer coating that allows indirect evaporative cooling in cSNAP was initially commercialized for waterproofing, anti-fouling, and other surface treatments. Not cooling. Or, in the case of the membranes for vacuum dehumidification, the engineering team built up expertise in making smart membranes for filtration; we simply asked if it could work for dehumidification. Spoiler: it doesn’t. But the expertise was on hand to quickly pivot to materials that were becoming more readily available and better suited for water capture. Today, the collaboration is in a different phase. Team members have a much better understanding of each other’s working methods and the value of collaborating. There’s far less of a “take and translate” mentality and more “yes and”: each side is better anticipating how this critical work benefits from other points of view.

The recent Vesma prototype was installed for two weeks in late August at HouseZero. Have you been able to conduct any early analysis from the collected data?

The team is thrilled with our early results. The field study goal was to prove we could effectively deliver refrigerant-free cooling in any climate using our novel vacuum membrane dehumidification and indirect evaporative cooling technology. We showed that the combined technologies, now named Vesma, can provide comfortable cooling more effectively than a typical vapor compression air conditioner. One way of proving this is by looking at the ratio of thermal energy removed to the electrical energy input or the coefficient of performance (COP). Vesma’s COP is above that of a typical air condition (COP > 4) and, under certain conditions, much, much higher. However, with any optimal system, we have to ask where things are less optimal. Vesma’s breakthrough is cooling using only water. The next big question was how much water the system uses for evaporative cooling. Throughout the study, we show that during certain conditions, the dehumidification system captures more water out of the incoming air than is used for cooling it. This is radical. However, on hot, dry days, we may only capture around 25 percent of the water we use for cooling. Finally, Vesma has a few ways of providing a thermally healthy environment. We can sensibly cool, we can dehumidify, and we can control the fresh air supply. We tested a half-dozen configurations to show we have several design degrees of freedom when providing a regenerative and effective cooling system. We’re excited to dive deeper into the data and see how to optimize for more human-centric cooling.

Is it possible for Vesma technology to be integrated into existing evaporative coolers in a cost-effective manner, especially with more industrialized systems?

This is somewhat a question of “market fit.” Our experience is that the building industry is a tough market to fit. Choose your “they” in the industry, but “they” have been doing things the same way for quite a while and making incremental improvements along the way. Vesma, and a few other companies we admire are disrupting the building cooling industry. We could integrate it into the existing system, but there is little appetite for it, especially when 50 percent of the market revenues are service contracts. Instead, we are targeting a cooling design that is a new or retrofit package for light commercial buildings (think replacing roof or wall units, not necessarily the mechanical penthouse). And not using refrigerants makes us even more disruptive. When it comes to market fit, it means we don’t have to sell through typical refrigerant-certified installers. Theoretically, any plumber, contractor, or handy owner can install Vesma because you just need to add water.

The water repellency of duck feathers is an inspiring phenomenon in nature that effectively insulates and cools various waterfowl. Can you explain the connection of down feathers and Vesma?

When we think about “new” materials, we think about a tiny fraction of society’s material history. The reality is that nature has evolved more beautiful and effective materials than we could ever design. For example, evaporative cooling is one of society’s first air conditioning methods used by “ancient” Egyptians and Persians. It’s a refined form of sweating, the same process that helps humans and other animals cool themselves through the phase change of water. In the case of duck feathers, whether contour or down, inspiration comes from the unique microstructures that enhance the bulk material’s performance. The contour feathers on the outside of the bird have a microstructure that locks the feather’s barbs together. This, combined with the duck’s own oils, which are worked into the feathers, creates waterproofing. In the case of cSNAP, we self-assemble a layer of alumina nanostructures on the ceramic and then functionalize them with an alkyl-group (oil-like compound) to make areas of the heat exchanger super hydrophobic and water-rejected. At the same time, other areas of the ceramic remain porous and hold the right amount of water for evaporation. Together, these dry and wet areas allow for powerful indirect evaporative cooling.

On the other hand, down feathers use small structures at the correct scale to trap air and create an insulating (and buoyant) layer. We think about the correct scale but do the opposite for both cSNAP and DryScreen. We design every feature in the system with tools like computational fluid dynamics to enhance heat and mass transfer. Effectively, we are trying to find geometry that promotes heat or vapor diffusion while limiting the energy needed to flow air across it, fitting form to flow. Typically, this means we are designing hierarchical structures with large surface areas—something closer to an elephant’s ears or a toucan’s beak.

Early refrigerants such as chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) have been phased out for environmental reasons and hydrofluorocarbons (HFC) have their own problems. It might be several years until a product like Vesma is on the market. In the meantime, what advice do you have for consumers who are seeking an environmentally friendly cooling unit?

Today’s HFCs have massive global warming potential (around 2000 times a single molecule of CO2). These chemicals typically leak before, during, and after an air condition system’s lifetime. The data are staggering. Societies’ global use of cooling (all cooling, not just buildings) has the potential to release many years’ worth of anthropocentric emissions by 2050; some say at least 60 Gtons of CO2e. For this reason, the Kigali Amendment outlines the gradual phase-out of HFC. This will likely happen with natural or organic refrigerants that have all been patented by the same slow-moving “they” mentioned above. Society found a good reason to phase out CFC, skin cancer. We are hopeful we can do it again with HFC. In the meantime, heat pumps using improved refrigerants are a good place to start. However, it can be more complex. As we rightfully push for more electrification, we must back it up with a larger and cleaner energy grid.

What is the greatest technological hurdle as this project advances and seeks project support and investment?

It’s exciting to say we know where most of our hurdles are. While we are in the very early productization phase, our collaborative team has driven Vesma’s discovery to an advanced level of development. The cSNAP indirect evaporative cooling unit was prototyped using industrial ceramic manufacturing with partners Gres Aragon in Spain. We have scaled up the barrier layer from a few square centimeters to many square meters (when you start designing something at the nanoscale, that’s more than ten orders of magnitude!). The bio-based polymers used in DryScreen have been tested and sourced with the industry. For the most part, the next phase of Vesma’s technical development will optimize the system-side design and integrate thermal controls (AI anyone). On the system side, we can certainly improve the vacuum pump; we expect three- to four-fold COP improvements using ready-to-ship pumps. On the thermal controls side, we are excited to distill enhanced thermal performance and optimal energy design into a single degree of freedom, simply asking the user, “Are you comfortable?”

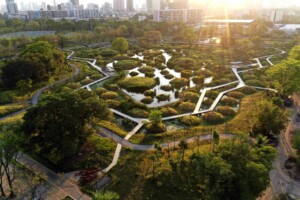

Kongjian Yu Wins 2023 Cornelia Hahn Oberlander International Landscape Architecture Prize

The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) has named Beijing-based landscape architect Kongjian Yu (DDes ’95) the winner of the 2023 Cornelia Hahn Oberlander International Landscape Architecture Prize , a biennial honor that includes a $100,000 award and two years of public engagement activities focused on the laureate’s work and landscape architecture more broadly.

Yu recently delivered the Sylvester Baxter Lecture at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), “Adaption: Political, Cultural, and Ecological Design—My Journey to Heal the Planet.” His guiding design principles are the appreciation of the ordinary and a deep embrace of nature—even of its potentially destructive aspects, such as flooding. Yu’s thinking about “ecological security patterns” helped shape environmental protection efforts throughout China. And his promotion of the “sponge city” concept, which uses landscape to capture, filter, and store rainfall for future use and reduce flood risks, helped to spur the Chinese government to launch an ambitious sponge city campaign across the country and has gained global attention.

Named in honor of the late landscape architect Cornelia Hahn Oberlander (BLA ’47), the Prize awarded by the TCLF is bestowed on a recipient who is “exceptionally talented, creative, courageous, and visionary” and has “a significant body of built work that exemplifies the art of landscape architecture.”

The international, seven-person Oberlander Prize Jury selected Yu from among more than 300 nominations from across the world. In naming the 2023 winner, the Oberlander Prize Jury Citation noted of Yu, he is a “brilliant and prolific designer … [who] is also a force for progressive change in landscape architecture around the world.”

“He lives and breathes his conviction that landscape architecture is the discipline to lead effective responses to the climate crisis,” said TCLF President & CEO Charles A. Birnbaum.

Gary R. Hilderbrand, Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture and Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, adds that Yu is the “all-time greatest spokesperson for landscape architecture in China—a nation that needs environmental rescue on a colossal scale.”

Yu is Professor and founding dean of Peking University College of Architecture and Landscape, and founder and design principal of Turenscape . His projects have won numerous international design awards, including 14 ASLA Excellence and Honor Awards and seven WAF Best Landscape Architecture of the Year Award. Yu is also the author of over 20 books and more than 300 papers and is the founder and chief editor of the internationally awarded magazine Landscape Architecture Frontiers. Yu was elected International Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2016 and received the IFLA’s highest honor, the Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe Award, in 2020, which celebrates a living landscape architect whose “achievements and contributions have had a unique and lasting impact on the welfare of society.”

The Cultural Landscape Foundation, founded in 1998, is a 501(c)(3) non-profit founded in 1998 to connect people to places. TCLF educates and engages the public to make our shared landscape heritage more visible, identify its value, and empower its stewards. Through its website, publishing, lectures, and other events, TCLF broadens support and understanding for cultural landscapes.

The Forest for the Trees (and the Birds, and the People, and the Planet)

As we continue to face the twin crises of rapidly accelerating climate change and biodiversity loss, city leaders and city residents are especially feeling the heat. The increasingly desperate need to radically cool cities is becoming widespread news , and the appointment of chief heat officers in cities as widespread as Athens , Miami, and Freeport, Sierra Leone , is a testament to the urgency of the issue. Many factors contribute to both the climatic challenges and the loss of biodiversity in cities (including, simply, the construction of buildings and streets), but one solution stands out: trees.

Trees are known for their inherent ability to provide shade, and therefore to cool the environment. In many cities generally, and especially in urban neighborhoods with predominantly Black, Brown, multi-ethnic, and socially vulnerable communities, the pervasive lack of a healthy tree canopy contributes to soaring temperatures and negative public health outcomes. This is just another way in which lower income, racially and ethnically diverse communities (often referred to as “environmental justice communities”) are impacted more significantly by the multiple effects of climate change.

The absence of trees also contributes to an increasing loss of ecosystem biodiversity and wildlife habitat, which in turn has detrimental effects on the environment as a whole (both in cities and beyond). And, with few or no trees in urban spaces, we reduce the opportunity to sequester carbon, to clean the air and the soil, to mitigate stormwater flooding, and to sustain healthy habitats for birds and other creatures–all critical functions of trees in healthy ecosystems–thereby exacerbating both the effects of climate change and the impacts of social and racial inequities.

Boston and Cambridge, along with many cities around the world, have recently developed their own urban forestry master plans to reverse these negative effects. They are creating new urban forestry divisions and leadership that will oversee implementation–including both care of existing trees and cultivation of an expanded tree canopy specifically adapted to tough urban environments. In many other places, like Los Angeles, city governments are partnering with educational institutions, non-profit organizations, and professionals to develop metrics-based, neighborhood-specific plans for the most impacted communities, from both environmental and social standpoints. In Dallas–Fort Worth, the non-profit group Texas Tree Foundation has been raising philanthropic dollars to fund and oversee the installation of tree plantings, advise on urban forestry plans in various cities in the region, and set up new training opportunities in the green labor force for those coming out of prison and looking to gain new skills and move on with their lives. Additionally, new “microforestry” efforts (also known as Miyawaki Forests) that dramatically increase species biodiversity in very small urban footprints are finally making their way from around the world into American cities and even into news coverage by the New York Times .

Most recently, as of the last week in September, Cambridge has its first urban forestry demonstration project at Triangle Park, in the Kendall Square neighborhood. The project is one of three small urban parks–two on “leftover” or underutilized parcels of land–that is meant to dramatically increase the amount and type of open space available to residents and workers in this part of the City. (My firm, Stoss Landscape Urbanism, was commissioned in 2016 to design both Triangle Park and the nearby Binney Street Park, which will open in 2024 as a park for dogs and people, while another Cambridge firm, MVVA, was commissioned to design the third park, Toomey Park, as a community gathering space and play area). Triangle Park in particular, was designated to embody the principles of the City’s urban forestry plan–in part as a test, in part as a demonstration–of this new commitment to trees, biodiversity, and innovative maintenance techniques tailored to this new mission.

“The design of this project was guided by the City’s Urban Forest Master Plan and includes significant tree plantings and canopy growth in the Kendall Square area,” said Public Works Commissioner Kathy Watkins. “It also allowed us to try some new approaches for how we think about open spaces and planting trees in the City. As the trees and plantings grow in over time, this unique park will provide an incredible shaded space in the heart of Kendall Square for residents and visitors to enjoy.”

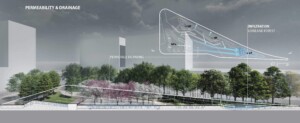

The site itself is small (three-quarters of an acre) but complex. At various times in his history, it was a tidal mud flat at the mouth of the Charles River, a fueling station, a parking lot for trucks, a dumping ground for urban debris, and an empty traffic island. It continues to be surrounded on all three sides by vehicular traffic–to the east and north by busy and noisy four-lane arterials, and to the west by a smaller connector street with an active retail/restaurant frontage. All this presented a series of challenges for transforming a compacted site with urban fill and contaminated waste to a healthy and thriving ecosystem that could support the growth of trees, shrubs, and groundcovers, and become the new center of the nearby community. These are challenges that were ultimately overcome by an extensive and collaborative team comprised of landscape architects, ecologists, arborists, maintenance specialists, environmental engineers, and others that are a combination of both city staff and hired consultants.

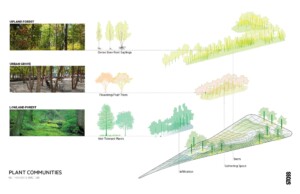

The design responds to these conditions and seeks to create a new space for trees and people to intermingle in a dense urban neighborhood. A berm along the eastern edge of the park marks the eastern edge of the site and screens the traffic and noise from Edwin Land Boulevard, allowing for elevational differences that enhance both social and environmental opportunities. On the back and top, it is planted with a variety of native upland trees and plant species (shagbark hickory, black oak, hackberry) in dense thickets that are designed to grow rapidly and to allow for natural competition and succession–an innovation in urban parks like this, one that requires an intense level of ongoing care and maintenance for which the City has committed resources and expertise. The inner side of the berm is inscribed with terraced lawns and linear seating walls, creating a welcoming and active social edge at the heart of the space–perfect for socializing, sunning, or reading. On the north, a lawn slope and stage are backed by woodland varieties and border forest floor (including American hornbeam, American smoketree, arborvitae, Eastern hayscented fern); these, too, screen out some of the noise and visuals of the nearby traffic but also create distance from the street to allow for more casual sunning, play, and performance activities. The very south end of the site–where the triangle comes to a very sharp and dramatic point, the earth is excavated to collect the site’s stormwater (a kind of green infrastructure stormwater “sponge”) and is overplanted as a lowland forest of Dawn Redwoods and a variety of birch species with an understory of ferns and witch-hazel. This feature even twenty years ago would have been non-existent, as conventional engineering techniques would have relied on pipes and infrastructure to flush the water away; here, instead, we deliberately retain the water on site into order to create ecological diversity and an environmentally healthy space. Finally, the central plaza–designed with a dramatic but abstracted parquet floor motif and rendered in white and black gravel–is populated with a combination of multi-stem River Birch and Kentucky Coffeetrees, which will provide a unique and richly shaded and flexible setting for people on scattered cafe table and chairs.

In all, the park includes almost 400 new tree plantings and introduces 15 new tree species to the collection of eight trees and four species already on site. This is quite remarkable on a site that measures just over three-quarters of an acre with a variety of spaces reserved for people and activities!

In a burgeoning neighborhood with very low levels of open space and urban canopy, this small city forest is impactful–and the social and environmental benefits will continue to grow and intensify over time, just as the trees themselves grow and take on wonderful shapes and characters. Equally important as these direct effects, the project is intended to serve as a test case and model for how the City of Cambridge implements its Urban Forestry Plan –and how cities across the country and around the world can benefit from what we learn moving forward. More tests and demonstrations like this are needed–so that we can collectively see how these projects mitigate and reverse the effects of climate change and biodiversity loss we are seeing now–and how cities can re-tool their own staffs and maintenance practices in order to better cultivate and care for these leading-edge, research-in-practice projects.

Curry J. Hackett and Gabriel Jean-Paul Soomar Win the Radcliffe Institute Public Art Competition

Harvard Radcliffe Institute recently announced Curry J. Hackett (MAUD ’24) and Gabriel Jean-Paul Soomar (MArch II/MDes ’24) winners of the biennial Radcliffe Institute Public Art Competition . The duo won for their innovative proposal titled HOLD, a 30-foot-long U-shaped enclosure designed to symbolize the spaces Black communities construct for themselves, nodding to the screened porches of the American South while acknowledging the cargo holds of slave ships. The artwork is expected to be unveiled at the Susan S. and Kenneth L. Wallach Garden on Brattle Street in May 2024.

The competition offers Harvard students an opportunity to showcase projects at the intersection of art, landscape design, and structural architecture. Participants compete for a prize that includes funding for the construction of the artwork and mentorship throughout the development and installation process.

HOLD is designed to be “an outdoor experience that acknowledges and celebrates the complicated relationship Black folks maintain with enclosure,” the artists said in a statement . The structure will serve as a reminder of the various ways in which Black mobility has been restricted (redlining, incarceration, slavery) while also calling to mind the spaces Black communities build for themselves (the Black church, the front porch, the hair salon)—spaces which signify safety and embrace. Hackett and Soomar intend for HOLD to be a gathering place for events and classes—a place “for Black students and underrepresented students across campus to find space and create space for themselves.”

This public art installation is the first for Soomar and the fourth for Hackett, although Soomar has seen his work exhibited at such notable institutions as New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Venice Biennale Architettura 2023. Hackett was also a shortlist candidate for the 2022 Wheelwright Prize.

The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University—also known as Harvard Radcliffe Institute—is one of the world’s leading centers for interdisciplinary exploration. We bring students, scholars, artists, and practitioners together to pursue curiosity-driven research, expand human understanding, and grapple with questions that demand insight from across disciplines. For more information, visit www.radcliffe.harvard.edu .

Adam Longenbach Receives 2023 Carter Manny Award Citation of Special Recognition

Adam Longenbach, a doctoral candidate in Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Urban Planning, was recently honored with a Carter Manny Award citation of special recognition from the Graham Foundation . He is also a 2023–2024 Graduate Fellow in Ethics at the Edmond and Lily Safra Center for Ethics and a 2023 Harvard Horizons Scholar.

Established in 1996, the Carter Manny Award program supports the completion of outstanding doctoral dissertations on architecture and its role in the arts, culture, and society. The only pre-doctoral award dedicated exclusively to architectural scholarship, it recognizes emerging scholars whose work promises to challenge and reshape contemporary discourse and impact the field at large.

In his dissertation “Stagecraft / Warcraft: The Rise of the Military Mock Village in the American West, 1942–1953,” Longenbach investigates the mid-twentieth-century entanglement of wartime policies, government agencies, private sector collaborations, and mass media technologies that led to the rise of military “mock villages.” His work connects this history to the ongoing production and operation of mock villages by militaries and police forces around the world, questioning what it means to replicate the built environment for the purpose of enacting violence in and against it.

Before coming to Harvard, Longenbach practiced for nearly a decade in several design offices, including Olson Kundig Architects, Allied Works Architecture, and Snøhetta, where he was the director of post-occupancy research. His writing can be found in Thresholds, The Avery Review, and Log, among others.

Martin Bechthold, Holly Samuelson, and Amy Whitesides Receive Project Funding from the Salata Institute Seed Grant Program

The GSD’s Martin Bechthold, Holly Samuelson, and Amy Whitesides are among the grant recipients of the first Salata Institute Seed Grant Program, launched in April to enable new interdisciplinary research in climate and sustainability. The program will support 19 faculty members working across seven Harvard Schools with funding for projects ranging from exploring a new, algae-based building insulation material to researching the carbon footprint of AI-driven computing.

Martin Bechthold, Kumagai Professor of Architectural Technology and Co-Director of the Doctor in Design Studies Program, is co-principal investigator on a project with Jennifer Lewis of the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. The team will research and develop a proof of concept for a carbon-negative insulation material made from microalgae, a cost-effective way to reduce buildings’ energy consumption and emissions.

Holly Samuelson, Associate Professor of Architecture, is the principal investigator on a project researching how architects can prioritize saving heating or cooling energy by analyzing the potential benefits of revising glass requirements. The optimal glass properties depend on not only building type and window orientation—variables already lumped together in today’s broad-brush building codes—but also properties of evolving heating systems and electricity generation.

Amy Whitesides, Design Critic in Landscape Architecture, is the principal investigator studying how forests play a crucial role in mitigating climate change. Agroforestry may offer means to diversify and protect lands that face encroachment and climate threats and often support lower-income communities. In support of the project, Whitesides will bring together landscape architects, planners, foresters, farmers, municipalities, and land management specialists.

Announcing the Harvard GSD Fall 2023 Public Program

The Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) announces its Fall 2023 schedule of public programs and exhibitions. Many of the season’s initiatives reflect on the relationship between design and the public good. Pritzker Architecture Prize recipient Shigeru Ban will present a lecture on balancing architectural practice and social engagement (September 19). Angela D. Brooks, housing justice advocate and president of the American Planning Association, will deliver the Rachel Dorothy Tanur Memorial Lecture (November 1). Featuring keynote speakers Germane Barnes, Renata Cherlise, Nina Cooke John, and Bryan Mason, the fifth biannual Black in Design conference (September 22–24), explores the multidimensionality of “The Black Home.” Rethinking the space of law and punishment is the focus of the Carceral Landscapes symposium (October 12–13), co-organized by the GSD and the Institute to End Mass Incarceration at Harvard Law School.

The program launches on September 12 with a release event for Harvard Design Magazine #51: “Multihyphenate,” featuring guest editors Sean Canty, Assistant Professor of Architecture, and John May, Associate Professor of Architecture, both from the GSD, and Zeina Koreitem, design faculty at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc). The associated exhibition Multihyphenation will be on display at the Druker Design Gallery August 30 through October 9, 2023.

The climate emergency provides an urgent touchstone for other programs, including the exhibition Our Artificial Nature: Perspectives on Design for an Era of Environmental Change (opening October 26). The presentation will spotlight research conducted at the Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities . In tandem with the exhibition, the GSD will host Carson Chan, curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, who will engage GSD faculty in a conversation about past design speculations, current research, and practice. Kongjian Yu, Professor and Dean, College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, Peking University, will lecture on ecological urbanism (September 14), and Tomás Folch, Design Critic in Landscape Architecture at the GSD, will discuss water in Andean cities (November 3).

The complete public program calendar appears below and can be viewed on Harvard GSD’s events calendar. Please visit Harvard GSD’s home page to sign up to receive periodic emails about the School’s public programs, exhibitions, and other news.

Fall 2023 Public Program

Multihyphenation

Exhibition associated with Harvard Design Magazine #51: “Multihyphenate”

Druker Design Gallery

August 30–October 9

Harvard Design Magazine #51: “Multihyphenate,” issue launch with editors Sean Canty, Zeina Koreitem, and John May

Frances Loeb Library

September 12, 12:30pm

Kongjian Yu

Sylvester Baxter Lecture

September 14, 6:30pm

Shigeru Ban, “Balancing Architectural Works and Public Contributions”

September 19, 6:30pm

Black in Design 2023: The Black Home

September 22–24

Tickets available through the conference website

Irma Boom and Remment Koolhaas, “Bookmaking”

September 27, 6:30pm

Michele De Lucchi, “Earth Stations: Future Sharing Architecture”

September 28, 6:30pm

Anita Berrizbeitia, “The Blue Hills: Charles Eliot’s Design Experiment (1893–1897)”

Frederick Law Olmsted Lecture

October 10, 6:30pm

Carceral Landscapes

Symposium

October 12–13

This event is co-organized by the GSD and the Institute to End Mass Incarceration at Harvard Law School

David Gissen in conversation with Sara Hendren

Loeb Lecture

October 17, 6:30pm

Manuel Salgado, “City Making”

Jaqueline Tyrwhitt Urban Design Lecture

October 24, 6:30pm

Our Artificial Nature: Perspectives on Design for an Era of Environmental Change

Exhibition

Druker Design Gallery

October 26–December 21

Angela D. Brooks

Rachel Dorothy Tanur Memorial Lecture

November 1, 6:30pm

Tomás Folch, “Hydraulic Geographies: Atlas of the Urban Water in the Andean Region”

Kiley Fellow Lecture, Room 112 Stubbins

November 3, 12:30pm

Lina Ghotmeh, “Living in Symbiosis–an Archeology of the Future”

November 6, 6:30pm

Pier Vittorio Aureli, “The Longhouse”

November 9, 6:30pm

Catherine Mosbach, “Design is a Language being Receptive being in Motion”

Aga Khan Program Lecture

November 14, 6:30pm

Opening of Our Artificial Nature: Perspectives on Design for an Era of Environmental Change

Thursday, November 16, 6:30pm

Conversation co-organized by the GSD and the Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities and moderated by Carson Chan, Director, Emilio Ambasz Institute for the Joint Study of the Built and Natural Environment, MoMA

All programs take place in Piper Auditorium, are open to the public, and will be simultaneously streamed to the GSD’s website, unless otherwise noted.

Registration is not required, unless otherwise noted. Please see individual event pages for full details and the most up-to-date information.

Welcoming 2023–2024 Pollman Fellow Tosin Fateye

The Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) is pleased to welcome Tosin B. Fateye as the Pollman Fellow in Real Estate and Urban Development for the 2023–2024 academic year.

Fateye is a lecturer at the Redeemer’s University, Ede, Osun State, Nigeria. Having completed his Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Estate Management (Real Estate Investment and Finance option) at the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria, he holds BSc and MSc degrees in Estate Management at the same University. He teaches and carries out research in the areas of real estate investment appraisal, property development and finance, and sustainable real estate. Fateye is an International Real Estate Business School (IREBS) Foundation Scholar, a corporate member of the Nigerian Institution of Estate Surveyors and Valuers (ANIVS), a member of the African Real Estate Society (AfRES), and a Registered Estate Surveyor and Valuer (RSV). Fateye’s writings have been published in real estate trade journals, and two of his conference papers have won IREBS/AfRES Best Paper Award in the Real Estate Investment and Finance, and Valuation categories in 2018 and 2021 respectively.

Fateye’s research focuses on real estate investment performance measurement using econometric models. While his previous works focused on assessing property investment performance using underlying market fundamental and technical analyses, he is interested in exploring the behavioral finance approach to evaluate real estate pricing dynamics for comprehensive and optimal investment decision-making.

One of the fellowships and prizes administered by the GSD’s Department of Urban Planning and Design, the Pollman Fellowship was established in 2002 through a gift from Harold A. Pollman. It is awarded annually to an outstanding postdoctoral graduate in real estate, urban planning, and development who spends one year in residence at the GSD as a visiting scholar.

The Black in Design Conference 2023 Receives Graham Foundation Grant

The Black Home , Black in Design Conference 2023, organized by Dora Mugerwa, Michael “MJ” Johnson, Kai Walcott, Tobi Fagbule, and Sean Canty, has been awarded a grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts . The Black in Design conference recognizes the contributions of the African diaspora to the design fields and promotes discourse around the agency of the design professions to address and dismantle the institutional barriers faced by Black communities.

The fifth biannual conference takes place September 22–24, 2023. This edition explores the multidimensionality of the Black home, which the organizers characterize as “a literal structure that shelters, as a reflection of culture and traditions, and as spaces that are not entirely physical.” Through keynote panels, workshops, and conversations, conference participants will develop a broader understanding of the Black home as part of “an effort to reinforce the ideals of Black communities living across the country and larger diaspora so that we can plan for its future.”

Founded in 1956, the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts makes project-based grants to individuals and organizations and produces public programs to foster the development and exchange of diverse and challenging ideas about architecture and its role in the arts, culture, and society.

Jingru (Cyan) Cheng Wins Harvard GSD’s 2023 Wheelwright Prize

Fellowship to support Cheng’s research proposal, an examination of the critical role of sand in human communities and the built environment.

Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD) is pleased to name Jingru (Cyan) Cheng the winner of the 2023 Wheelwright Prize , a $100,000 grant to support investigative approaches to contemporary architecture, with an emphasis on globally minded research. Her project, Tracing Sand: Phantom Territories, Bodies Adrift, focuses on the economic, cultural, and ecological impacts of sand mining and land reclamation. From airports to beaches and river basins to hydroelectric dams, sand is a humble material that has a fundamental role in the built environment and human communities. Supporting modern cities and modern life, sand is a key component of concrete, glass, asphalt roads, and artificial land. However, by dredging underwater systems and channels, sand mining erodes riverbanks and disrupts ecosystems. Colossal amounts of sand are mined and moved to shape one habitat while destroying another.

The Wheelwright Prize will fund two years of Cheng’s research and travel, including visits to airports in Singapore, beaches in Florida, rivers in the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, and rural immigrant communities in China. Investigating how sand is mined and used in these diverse sites, Cheng will conduct interviews with key stakeholders and research design decisions, procurement routes, contractual relations, financing, regulations, and policies. She also plans to develop educational and public programs, and a multi-media archive that will be open access and made available for the affected communities, activist groups, and associated researchers.

“The proposal of Tracing Sand is the convergence of my different lines of work so far, the teachings that made me an architect, and the life experiences that made me. I see architectural materiality as an active, tangible force driving and shaping long chains of consequences and dependencies. It draws surprising connections between sites, communities, and ecologies. Winning the Wheelwright Prize affirms that the questions I’m after are part of the larger quest of architecture today, at a time of intensified social injustice and ecological crisis,” Cheng says. “As a travel-based design research award, the Wheelwright cannot be more fitting for this rather audacious proposition: to follow sand is to trace architectural materiality through supply chains and ecosystems. It is to learn through embodied experiences the entangled flows of people, life forms, matter, and the built environment across scales. Understanding how interconnected and interdependent we all are is fundamental today. I believe architecture provides a material wayfinding through this almost incomprehensible entanglement—and offers possibilities to transform it.”

“In his book The World in a Grain (2018), American-Canadian journalist Vince Beiser underscores why sand affects each and every one of us: ‘It is to cities what flour is to bread, what cells are to our bodies: the invisible but fundamental ingredient that makes up the bulk of the built environment in which most of us live.’ Cyan Cheng’s Wheelwright proposal takes Beiser’s claim one step further: sand underpins our built environment, but also our global economy,” says Sarah M. Whiting, Harvard GSD’s Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture. “Tracing together material evidence, technological expertise, labor practices, and corporate reach, Cheng’s study has breadth that makes it relevant to every community across the globe, and specificity that promises to reveal hitherto unknown repercussions of this fragile resource.”

Jurors for the 2023 prize include: Noura Al Sayeh, Head of Architectural Affairs for the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities; Mira Henry, design faculty at Southern California Institute for Architecture; Mark Lee, Professor in Practice of Architecture at Harvard GSD; Jacob Reidel, Assistant Professor in Practice of Architecture at Harvard GSD; Enrique Walker, Design Critic in Architecture at Harvard GSD; and Sarah M. Whiting, Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture at Harvard GSD.

“Tracing Sand examines an increasingly ubiquitous material that is at the base of the production of land and architecture by following its sourcing and consumption, unveiling the increasing entanglement of matter and site, as well as the livelihoods affected by its extraction,” observes Noura Al Sayeh, Head of Architectural Affairs for the Bahrain Authority for Culture and Antiquities. “By dissecting the complexity of material supply chains and the complicity of architecture in the destruction of natural environments, Cyan’s research bridges opposing sites and actors, from extraction to consumption, local communities to stakeholders. Through a multi-media approach and an in-depth analysis of the guts of hypermodernity, the proposal aims towards a comprehensive shift in the value system of architecture.”

The Wheelwright Prize supports innovative design research, crossing both cultural and architectural boundaries. Winning research proposal topics in recent years have included the potential of seaweed, shellfish, and the intertidal zone to advance architectural knowledge and material futures; how spaces have been transformed through the material contributions of the African Diaspora; and new architecture paradigms for storing data that can reimagine digital infrastructure.

Cheng was among four distinguished finalists selected from a highly competitive and international pool of applicants. The 2023 Wheelwright Prize jury commends finalists Isabel Abascal, Maya Bird-Murphy, and DK Osseo-Asare for their promising research proposals and presentations. Jingru (Cyan) Cheng follows 2022 Wheelwright Prize winner Marina Otero, whose Wheelwright project, Future Storage: Architectures to Host the Metaverse, is currently in its travel-research phase.

About Jingru (Cyan) Cheng:

Jingru (Cyan) Cheng works across architecture, anthropology, and filmmaking. Her practice follows drifting bodies—from rural migrant workers to forms of water—to draw out latent relations across scales, confronting intensified social injustice and ecological crisis. Cheng received commendations from the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) President’s Awards for Research in 2018 and 2020. She is also a 2022 Graham Foundation Grantee. Her work has been exhibited internationally as part of Critical Zones: Observatories for Earthly Politics at ZKM Karlsruhe, Germany (2020–2022), the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism (2019), the Venice Architecture Biennale (2018), among others, and is included in the Architectural Association’s permanent collection. Cheng holds a PhD by Design and MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design (Projective Cities) from the Architectural Association (AA), and was the co-director of AA Wuhan Visiting School (2015–2017). She co-led the MA architectural design studio Politics of the Atmosphere (2019–2022) and currently teaches an interdisciplinary module across all schools at the Royal College of Art in London.

About the 2023 Wheelwright Prize Finalists:

Isabel Abascal: Mother Architecture: Shaping Birth

Isabel Abascal is a Mexico City–based architect and writer. In 2015, she founded the architecture studio LANZA Atelier, along with Alessandro Arienzo. From 2015 to 2017, Abascal was the Executive Director of LIGA, Espacio para Arquitectura, a platform dedicated to the dissemination and discussion of Latin American architecture. There, she curated myriad exhibitions, and co-edited the book Exposed Architecture, published by Park Books. She has also contributed to publications such as DOMUS, Avery Review, Arquine, Wallpaper*, and the UNAM Journal, among others. Abascal studied architecture at the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, the Technische Universität in Berlin, and at the Vastu Shilpa Foundation in Ahmedabad, under Balkrishna Doshi.

Maya Bird-Murphy: Examining Architectural Practice Through Alternative Methodology and Pedagogy

Maya Bird-Murphy is a designer, educator, and the founder of Mobile Makers, an award-winning non-profit organization bringing design and skill-building workshops to underrepresented communities. She was selected by Theaster Gates and the Prada Group as an Experimental Design Lab awardee, featured as one of 50 people who shape Chicago in Newcity Magazine, and received the 2022 Pierre Keller Prize at the Hublot Design Prize ceremony in London. In 2018, she was named as an AIGA Design + Diversity Conference National Fellow. The same year, she was featured in The American Institute of Architects’ (AIA) Emerging Professionals Exhibition 2018 for Mobile Makers. Bird-Murphy attended Ball State University and received an MArch from Boston Architectural College.

DK Osseo-Asare: Bucky in Africa: Remembering the Chemistry of Architecture

DK Osseo-Asare is a Ghanaian American designer who makes buildings, landscapes, communities, objects, and digital tools. He is a co-founding principal of the transatlantic architecture and integrated design studio Low Design Office (LowDo), based in Austin, United States, and Tema, Ghana. He holds an appointment in Humanitarian Materials at the Pennsylvania State University, where he directs the Humanitarian Materials Lab, a transdisciplinary research lab architecting materials for human welfare. He is a TED Global Fellow; member, Ghana Institution of Engineering (GhIE); and received AB in Engineering Design and MArch degrees from Harvard University, with a focus on kinetic architecture and network power.