“A crash course in loving”: Oana Stănescu remembers Virgil Abloh

“I have been refusing to put words down, afraid they might make real something none of us is anywhere close to accepting: Virgil Abloh, the architect, fashion designer, possible prophet, exquisite DJ, eternal collaborator, and brilliant friend, husband, father, and son, has died after privately battling a rare, aggressive form of cancer for over two years.

We had known each other for years, and worked together on too many projects to count when I invited him in 2017 to give a talk to our small student cohort of the Core 3 design studio at the GSD. Before we knew it, we got calls from the administration, asking: “Is Virgil Abloh giving a lecture? High school students have been calling to ask if they can attend.” Well, they didn’t just attend, they showed up, hours early, lining the walls of the GSD for what was, for many, their first lecture. And with that, all sorts of people whose lives would otherwise unlikely intersect, filled the lecture hall to the brim. No other single voice was able to connect with youth in the past troublesome decade the way Virgil did, and he did so naturally, because he was youth incarnate. The rest is living history. The talk became the GSD’s most watched lecture, followed by Incidents, the instantly sold-out transcript of the lecture, which was ultimately translated into Japanese.

Last summer—that 2020 summer—he wanted to see what we could do to bring architecture schools closer to the streets. We had been trying for years, in various ways, to cross what felt like a disconnect between the profession and education, between skill and purpose. Within two months, we created a seminar at the GSD in collaboration with the Stanford Legal Design Lab, where law and architecture students were working together, addressing the real-time changes the justice system was undergoing due to the pandemic. Virgil noted, “That invisible hand of design is why this course exists, because it’s often easy to say, ‘Hey, that’s not our responsibility,’ but ultimately, our human responsibility is to make it so that everyone can understand the basic premise of design, which is the basic premise of helping people.” It takes an incredible amount of work and luck for all the stars needed for this project to align, but Virgil liked aiming for the stars. And time and time again, he was able to reach for new heights, with his vision, his humbleness, and a generosity of resources.

The first grieving email I received last Sunday was from a former student: “I can’t explain how powerful it was to witness a Black designer speak so directly to us young people.” Virgil meant so many things to so many people: I keep thinking of him as a glue that held people together, the conduit to so many great leaps, the spark to so much trouble. If you drew a map of his reach, it would cover the world. This pertains to fashion, to music, to design, to philanthropy, but really, it’s about a spirit that transcended any definition. That was the very point.

Few people achieve in a lifetime what Virgil Abloh did in too short of a time: he broke the odds, not just once, for fun, but as a rule. It’s not that he didn’t face obstacles. On the contrary, he chose to ignore them as such, use them as a springboard, revealing their hypocrisy and limitations, carving a path not just for himself, but for generations to come. It’s hard not to smile between the tears, because he always shared his lust for life freely and his infectious, raspy laughter.

It was also 2017 when I told him about my own cancer diagnosis and he texted back in a heartbeat “Love you, cancer can’t stop us.” We didn’t know the cards we were dealt. A couple of weeks ago, as we were talking through the impossible challenge of such an illness, he said something very powerful: “What a crash course in loving this task deals us.” It struck me how universal, how true, how well it encapsulates life at its hardest. And this is the task we have been dealt now, too, a crash course in loving.

In doing so we will continue to live in a world shaped by him and while the world is certainly lesser without Virgil, we were lucky to have had him in the first place.”

Fostering Relationships Between Insects and Humans Through Design

Insects are indispensable creatures: vital pollinators, crucial recyclers of waste, the foundation for food webs around the globe, and a unique resource for medicinal purposes. As bioindicators, they are harbingers of ecosystem change. Yet they are often considered threats, plagues, or merely irrelevant, making them some of the most misunderstood animals on Earth.

Gena Wirth, design principal at SCAPE studio and visiting professor at the GSD’s Department of Landscape Architecture, is leading a studio that asks students to take a much closer look at these valuable species. Starting from the premise that “the health of insect populations is directly tied to the health of our landscapes,” “ENTO: Fostering Insect/Human Relationships through Design” prompts students to investigate human/insect dynamics and design for insects using a multidisciplinary and research-driven lens, and engaging with experts of ecology, entomology, horticulture, and landscape architecture.

We need to slow down a little bit and look more closely at what insects are telling us, at what their presence is telling us, at what their chemical composition is telling us. And, really view them as valuable cohabitants of the world that we live in, not as pests to smash or things to spray.

Estimates suggest that there are about 10 quintillion live insects on Earth, which is the equivalent of around 1.4 billion for every human. Of this staggering number, scientists have identified an estimated 5.5 million varieties, meaning insects represent close to 80 percent of the world’s living species. But research indicates their numbers are rapidly decreasing. “I think there’s a general consensus in the entomology community that we have a large-scale problem with insect decline,” Wirth says. In 1987, E.O. Wilson, also known as the father of ecology, gave an address at the National Zoological Park in Washington, DC, referring to invertebrates, and especially to insects, as “the little things that run the world.” Back then, Wilson also famously said: “If invertebrates were to disappear, I doubt that the human species could last more than a few months.”

“Urban environments and the way that we develop and build life on land is not necessarily helping or accelerating most insect life,” Wirth explains. Intensive farming, broadcast pesticide applications on crops, and climate change are altering populations. And many insects are susceptible to global warming: “They are very temperature-sensitive, and even the smallest changes can trigger large movements of species, the seeking out of new habitat types, and the adaptation to new environments,” Wirth says. Even seemingly innocuous human activity can affect insect development. Wirth uses the example of fireflies, which have evolved to lay their eggs on leaf litter. Something as common as a raked grass landscape means they can no longer reproduce or survive.

There is a lot about insects that is yet to be understood—including the exact size of their populations. And since many have not yet been discovered, it’s difficult to grasp the extent of their decline. “It’s almost like, we think there is a big problem, but we don’t know how big or what exactly is happening,” Wirth explains. “That’s the kind of space that design can operate well within. We’re a field that needs to propose action, adaptation, and change. We have to work in this environment of uncertainty, test new ideas, and put thoughts forward. So that’s really the aim of the studio: to test and foster new insect/human relationships using our design language and tools.”

As Wirth points out, there are many inspirational thinkers in the overlapping fields of insect conservation, gardening, and horticulture. “I would say that there is a trend towards ecological gardening, or a kind of backyard scale habitat improvement, which I think is having some momentum in the greater public discourse,” she says.

At the beginning of the semester, students traced relationships between certain insect taxa in rural, suburban, and urban sites of eastern Massachusetts. Field trips allowed them to take a closer look at insects and the impact many of these species could have on a single habitat. In one outing, the group participated in a guided tour with Harvard Forest’s Greta VanScoy, education coordinator & field technician, and David Orwig, senior ecologist and forest ecologist. They are researching the hemlock woolly adelgid, an invasive insect, native to Japan, that targets hemlock trees in North America and has killed millions of them in the eastern US. “We got to see first-person, from their perspective, the impact of one single species on an entire forest type that covers and blankets New England,” Wirth explains.

In the studio, students are conducting projects focused on particular species—investigating habitat requirements and needs during all the phases of the life cycle, as well as any changes that have been occurring. This advanced research is expected to develop into site-based design proposals. Although Wirth believes all insects should be preserved, she is careful not to impose such an opinion on her students. “Ultimately, the goal of the studio is to have [them] reflect on what is the existing [human] relationship with the species they chose, which might be one of admiration, or in the case of fireflies, for example, nostalgia but also neglect. Ignorance is also a relationship we have with many species that we don’t even know exist or know anything about.”

Students are not only defining the relationships that currently exist between insects and humans, but also determining the sorts of relationships they want to foster with their design process. Wirth notes, “Some of those are about expanding and supporting habitat needs or living in a more mutualistic or beneficial way with insects. And some are about being defensive with them. But that is all completely up to students and is very species- and project-specific.”

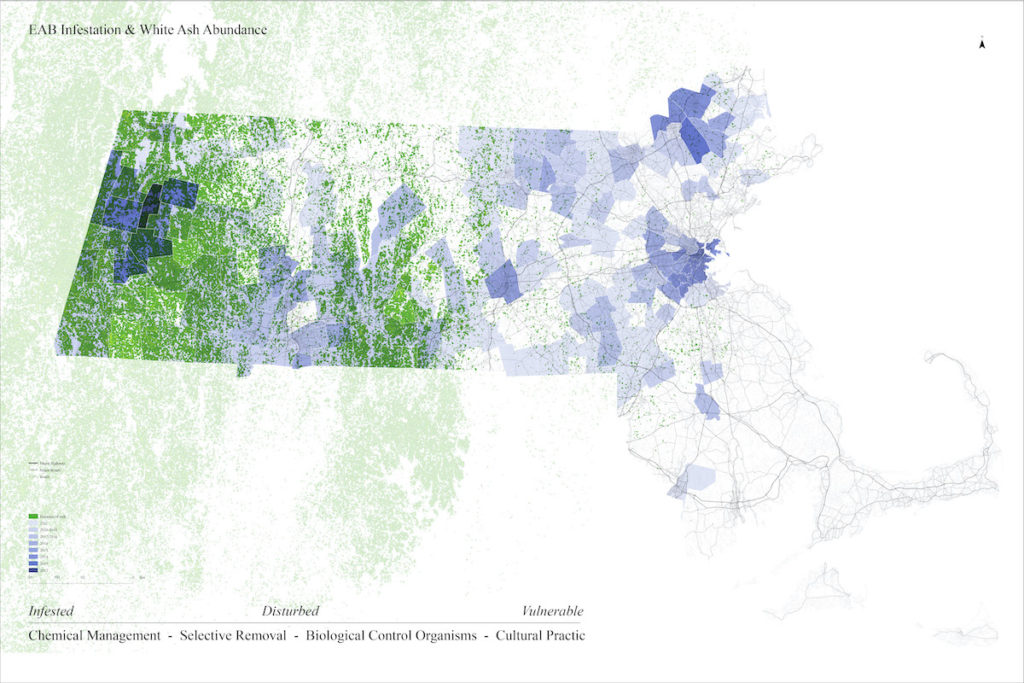

Sijia Zhong (MLA I AP ’22) is focusing on the emerald ash borer, a non-native wood-boring beetle that has been deemed one of the most significant threats to North American forests. As Zhong explains, the beetle—which is indigenous to northeastern Asia and was first identified in Michigan in 2002—was probably brought to the West through the global trade of wood products or packing materials. This invasive borer has already killed millions of trees and is a continuing threat to native ash trees.

One part of Zhong’s project is aimed at the economic impact this species poses to communities who find themselves having to remove dead ash trees by the thousands. Her design will address this issue by proposing “an on-site alternative to dispose and reuse the deadwood left by the emerald ash borer, and developing an urban deadwood habitat system to utilize the aftermath of infestation for nitrogen-fixing and local biodiversity restoration.”

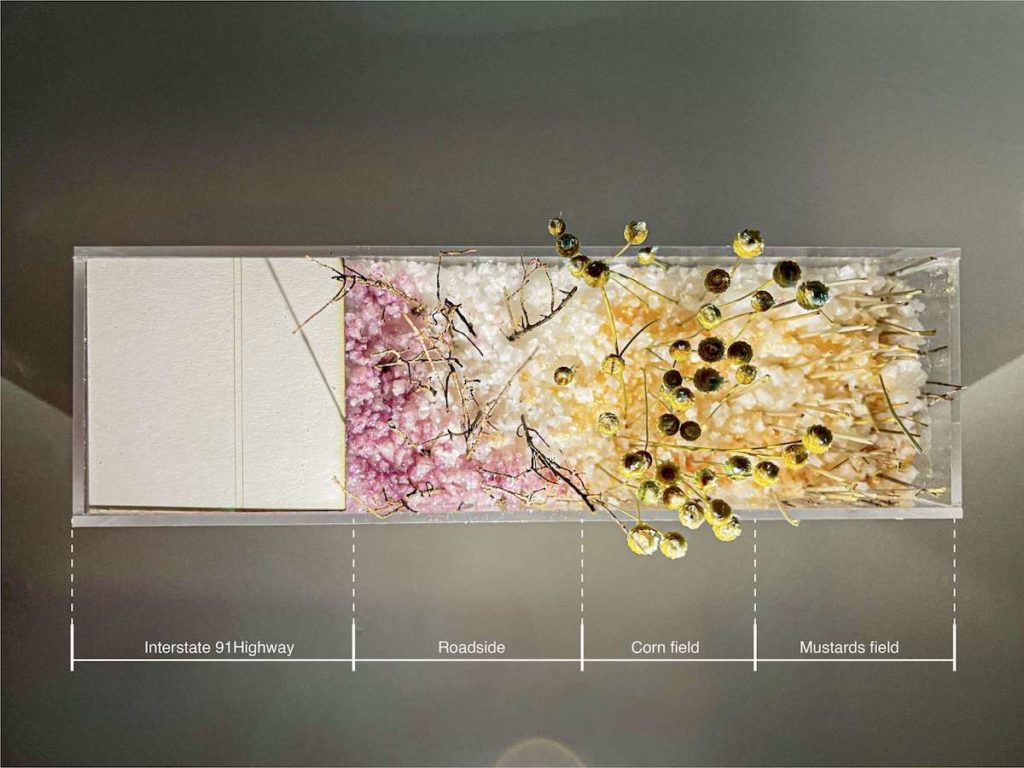

Liwei Shen (MLA I ’22) and Hyemin Gu (MLA I AP ’22) are researching the impact human activity has on monarch and cabbage white butterflies close to the I-91 highway, specifically due to the accumulation of chemicals such as zinc (emitted by cars) and neonicotinoids (heavily used in agriculture). Monarchs are vulnerable since they feed off milkweed, which grows on roadsides absorbing pollution, while the cabbage whites—an invasive species hailing from Europe—are much more resilient to harsh conditions. The duo is developing an “environmental justice” solution by designing butterfly corridors with vegetation species that can absorb pollutants and create balanced habitats.

Since Shen and Gu are looking at the highway, the roadside, and agricultural sites alongside the roadside, they are also interested in the way human needs, particularly local farmers’ needs, can intersect with those of the butterflies they’re studying. “We’re working with butterflies at the edges of farmlands, [so] we are also thinking about creating healthy environments for both human and non-human species,” they explain.

“No inch of the world is untouched by human impact,” Wirth says. Even landscapes that don’t appear to be affected by humans are reshaped by the innumerable human activities that accelerate climate change. “We are impacting these places. We are a part of these ecosystems. And we have to figure out how to be a better, more compatible part. I think that involves bringing in the greater suite of design tools. We need to slow down a little bit and look more closely at what insects are telling us, at what their presence is telling us, at what their chemical composition is telling us. And, really view them as valuable cohabitants of the world that we live in, not as pests to smash or things to spray.”

Kingston University London’s Town House, Engineered by Hanif Kara’s AKT II and Designed by Grafton Architects, Wins 2021 Stirling Prize

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) has awarded Kingston University London’s Town House the 2021 Stirling Prize . Currently in its 25th year, the Stirling Prize is RIBA’s most prestigious award. It is given annually to a new building in the United Kingdom considered to have made a significant contribution to the discourse of architecture in the past year.

Structural engineering for the Town House was provided by AKT II , the global firm co-founded in 1996 by Professor in Practice of Architectural Technology Hanif Kara. The building was designed by Dublin-based architecture firm Grafton Architects . Founders Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara held the GSD Kenzo Tange Chair in 2010. Last year, Grafton Architects won the Pritzker Architecture Prize and the RIBA Gold Medal.

Town House is described as a welcoming and transparent public place. It celebrates and encourages human encounters with large public terraces, wide staircases, and open-plan study areas that look across dance studios and performance spaces. Speaking for the Stirling Prize jury, Lord Norman Foster describes the building as “a theatre for life—a warehouse of ideas. It seamlessly brings together student and town communities, creating a progressive new model for higher education, well deserving of international acclaim and attention. In this highly original work of architecture, quiet reading, loud performance, research, and learning can delightfully coexist. That is no mean feat.”

The project marks the fourth time since 2000 that AKT II has been honored with the Stirling Prize. Previous wins include the Peckham Library and Media Centre in 2000, the University of Cambridge Sainsbury Laboratory in 2012, and the Bloomberg Headquarters in 2018. As design director at AKT II, Kara follows a “design-led” approach in his practice. His interest in formal innovation, materiality, sustainability, and complex analytical methods have allowed him to work on multiple groundbreaking projects and address many of the challenges facing our built environment.

In 2018, Kara spoke with Travis Dagenais about the research, engineering, and collaboration behind the Stirling Prize-winning Bloomberg headquarters in London.

Climate Change, Water Rights, and the Future of the Mexican Altiplano: An interview with Lorena Bello

The recent United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow offered fresh evidence of the unbridled global climate crisis, and reminded us that while humanity faces unprecedented threats, some communities are bearing an undue portion of the burden. GSD Design Critic Lorena Bello Gómez’s research combines landscape, architecture, and urbanism to mitigate that burden for environmentally vulnerable communities. As an urbanist, she is interested in how design at the territorial scale can address flawed policies and infrastructures to reduce injustice.

This semester, Bello is teaching “Aqua Incognita: Deciphering Liquid Territories in the Mexican Altiplano.” Using a water-scarce region in the hinterland of Mexico City as a case study, studio participants are designing sustainable and scalable pilot projects to help this farming region confront the fallout from unsustainable industrialization and the active threats to local livelihoods posed by climate change.

How has your practice informed the Aqua Incognita studio?

For five years, I have been looking at territories beyond cities that are engulfed in climatic risks. I typically work with local foundations in collaboration with interdisciplinary teams, raising support through international grants. My current project looks at the Apan Plains, an area 80 kilometers from Mexico City. The city and the plains form a single region climatically, in terms of water resources, fluxes, and metabolism. But they don’t have any other connection, which creates tensions. There’s a political divide because these plains belong to another state, Hidalgo, with different policies, governor, and political agendas. And while Mexico City is always in the spotlight of climate crises; the Apan Plains don’t get into the news. This absence of visibility makes them vulnerable to climate change and to other environmental injustices.

The studio is positioned to respond through design to the cultural, political, biophysical, and socioeconomic structural issues that are placing pressure on this liquid territory. We are supported by a UKPACT international grant to build capacity for implementation and to establish trust with local stakeholders.

As climate crises increase, the new regimes of too much or too little water that don’t allow you to farm are also increasing. This requires a more equitable access, provision, treatment and reuse of water resources. Designers can provide scenarios showing the gains of such redistribution.

What can you tell us about these pressures?

In the 1920s, after an agrarian revolution, lakes were drained and land was given back to farmers as commons or ejidos. Mexican land is communally owned and individually farmed, a trend diminishing over time as the nation entered a neoliberal era. After NAFTA, in 1992, land could be privatized and transferred from common land to dominio pleno, or private land. Mexico is still urbanizing peri-urban areas in the outskirts of cities, transforming ejido land to urban land.

In Apan, land has been abandoned or overexploited through industrialization. Adding to farmer’s challenges, in 1954, the national government determined that the Apan Plains’ aquifer, linked hydrologically to Mexico City’s, could not be used by local farmers. Instead, the national government has granted aquifer access to many industrialists. There are now global beer and paper industries, metal companies, and solar farms in the valley, all using aquifer water needed by communities.

So, the crux of the issue is access to—and control over—water resources?

Yes. On the one hand, you have a population who depends on their land yet only have access to rainwater. Then you have the urban areas of the valley together with these industrialists, that have access and are depleting the aquifer—as nobody measures consumption.

This, along with the privatization of land, is causing water-intensive processes and erosion, since Apan Plains’ municipalities lack urban plans to protect critical environmental zones and resources.

Does the course look at a particular kind of solution?

The studio is testing hypotheses through design, working closely with Mexican and global experts in law, urban sociology, ecology, agronomy and environmental sustainability. This interdisciplinary team provides students a holistic view of the intertwined structural challenges that these communities are facing.

At selected settlements of ~2,000 people, students are designing aquacultural projects that improve the hydrological region in a bottom-up fashion. They are integrating formerly siloed areas of scientific knowledge to build spatial connections, creating processes that enhance positive feedback loops and decrease waste. They are designing systems, not objects.

Can you give me examples of potential solutions to any of the problems that you’ve mentioned?

Farmers can be helped to reforest and transition from barley monoculture into more sustainable and profitable agriculture. This will in turn diminish the amount of pesticides and agrochemicals that go into the aquifer and water bodies, and improve the quality of soil—which is arid—in order to amplify wetness.

As climate crises increase, the new regimes of too much or too little water that don’t allow you to farm are also increasing. This requires a more equitable access, provision, treatment, and reuse of water resources. Designers can provide scenarios showing the gains of such redistribution.

What kind of experience have you created for your students?

The Apan Plains make visible and tactile the challenges that vulnerable human/non-human communities are facing. Students heard this in first person from different stakeholders and they had the opportunity to get a lot of feedback. In this sense, Aqua Incognita gives them an active voice in reducing such vulnerabilities with projects that must anticipate: resistance among actors, low budgets, low management and maintenance—not dissimilar from greening plans in Europe or the US.

When I think about landscape architecture, I imagine gardens. What does landscape architecture mean in the context of this work?

Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted was one of the first designers to think systemically about the metabolism of cities, with large visionary projects that move beyond gardens and become a kind of regional design. To me, it is an excellent way to think about sustainable regions today: How do you enhance the metabolic cycle of resources? How do you start closing cycles instead of linear structures that leave things open? So, part of the approach of the studio is to think about water circularly, moving from a myopic understanding of solutions to a holistic understanding of problems.

UKPACT project collaborators include Antonio Azuela, Charlotte Chambard, Diane E. Davis, Gabriela Degetau, Gustavo Madrid, Raúl Mejía, Samuel Tabory, Monica Tapia, and Luis Zambrano. Student researchers include Ying Dong, Lauren Duda, Angel Escobar-Rodas, Barbara Graeff, Xingyue Huang, Jingyun Li, Hala Nasr, Sophie Mattinson, Alison Maurer, Morgan Vogt, and Maria Vollas.

2021 Chicago Architecture Biennial features a range of projects by the GSD community

The Chicago Architecture Biennial (CAB) returns this year with its 2021 edition, The Available City, conceptualized by artistic director David Brown. According to the CAB website, this fourth installment “is a framework for a collaborative, community-led design approach that presents transformative possibilities for vacant urban spaces that are created with and for local residents. Through workshops, installations, activations, performances, and programs, The Available City invites a critical global conversation that asks how design can foster collective engagement and agency to identify new forms of shared space in urban areas. The Available City directly confronts the often- opaque process of how cities are designed and developed by proposing an inclusive and transparent design process.”

The Available City opened across a variety of sites in Chicago on September 17, and runs through December 18. A range of Harvard GSD faculty and community members are participating in The Available City.

Paola Aguirre (MAUD ’11) and her practice Borderless Studio have contributed Frame(Works) of Resilience. The installation builds on the four-year long project Creative Grounds, which uses design to bring visibility to the almost fifty public schools that have closed in the West and South sides of Chicago. Located at the Overton Incubator, Borderless Studio’s work for CAB includes a new community garden and an outdoor pop-up market with colorful canopies inspired by street market design.

Rekha Auguste-Nelson (MArch ’18), Farnoosh Rafaie (MArch ’18), and Isabel Strauss (MArch ’21) and their recently formed Riff Collaborative have installed Architecture of Reparations at CAB’s Bronzeville Artist Lofts site. Their project began with two years of research into the Bronzeville neighborhood, specifically the displacement of Black residents. A public Request for Proposal (RFP) entitled Architecture of Reparations resulted, telling the story of erasure in Bronzeville, and proposing reparations in the form of housing. In the second phase of the project, they responded to the RFP using vacant and available city-owned land.

Germane Barnes, winner of the GSD’s 2021 Wheelwright Prize, has collaborated with Shawhin Roudbari and MAS Context to present Block Party at CAB’s Bell Park venue. According to the CAB website, the installation—along with its accompanying workshops and events—“serves as a site to discuss the modes by which the built environment promotes or restricts Black space and to call attention to the systemic forces that create blight in communities of color.”

Sekou Cooke (MArch ’14) has installed Grids + Griots, invoking a theme from Cooke’s book Hip-Hop Architecture, at CAB’s YMEN (Young Men’s Educational Network) North Lawndale Bike Box venue. Tension between the image and attitude of the griot (a storyteller in western African cultures) with that of modernist and postmodernist architectural practice underlies Grids + Griots. The CAB website explains, “This design brings together several elements already present on the site and others present in the larger context, each formed using parts of a forty-foot-long shipping container. The pavilion repurposes existing materials, chops them up, and remixes them into a new composition able to be recomposed as needed.”

Jill Desimini, associate professor of landscape architecture, has contributed Staged Succession: An Argument for Urban Landscape Mash-ups, an essay considering what communities could do with the estimated $500,000 to $2 million that public land banks spend mowing their holdings of vacant land, and how communities might loosen the strangleholds of policy and predatory lending to be able to transform property. “Actively caring for a site is, in other words, very different from simply abandoning a space and letting it go,” Desimini writes. “It requires, above all, a drastic shift in perspective away from the either-or mentality of current practice—of mowing or not mowing, of clearing or not clearing, of planting or not planting, of building or not building. As the binaries disappear, the balances shift. Think hybrids, cyborgs, and mash-ups between mown and unmown and suppressed and wild. We can look for other mash-ups—abandoned and owned, improvised and rehearsed, unregulated and decreed.”

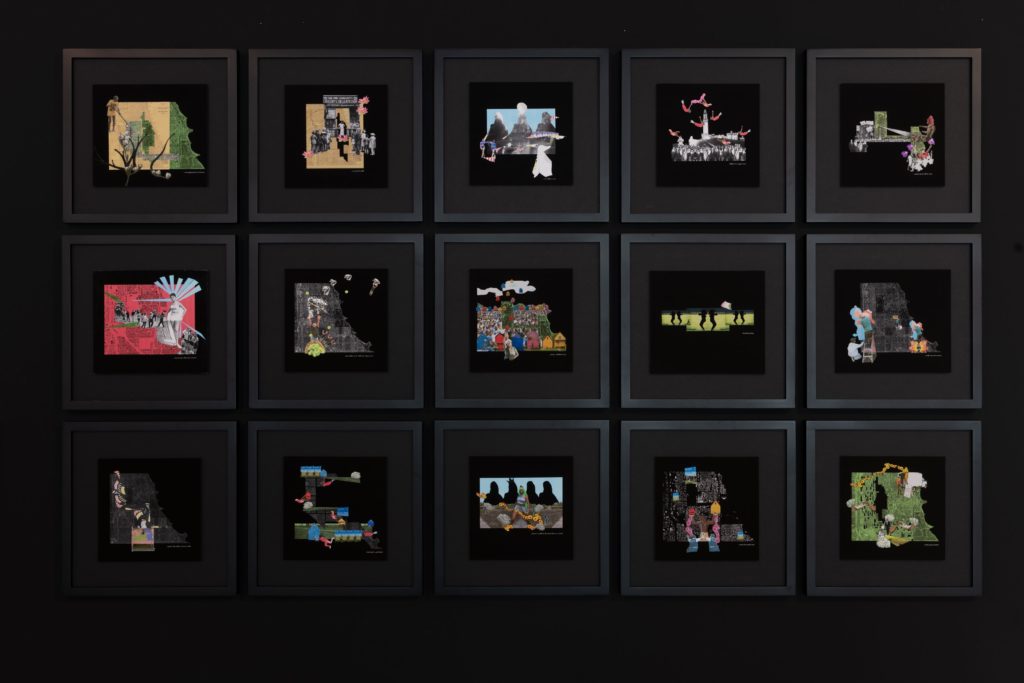

Toni L. Griffin (LF ’98), professor in practice of urban planning, and her New York–based practice, Urban American City (urbanAC), have installed Southside Landnarratives in CAB’s Bronzeville Artist Lofts site. According to the CAB website, “This exhibition of collages represents the confrontation of pain and quest for joy found in the Black public realm of Chicago’s Mid-South Side. Each collage, which was assembled by hand and digitally reproduced, illustrates the relationship between publicness for Black Americans and the current urban landscape of vacancy, from southern migration in response to public denial, the public scars left by urban renewal’s land mutilation, and the relentless pursuit of public freedoms in the public realm.”

Walter Hood, Harvard GSD’s Spring 2021 Senior Loeb Scholar, and his Oakland-based Hood Design Studio have designed a site of new Witness Trees, referring to the trees that still bear witness even hundreds of years after significant events. The CAB website describes the installation: “Tree grids are scaled to the site: at the corner of East 53rd and South Prairie Avenue, a grid is painted on the lawn at ten-foot intervals, and a grid of sixteen Bald Cypress trees sit at the site’s center. Through the planting of southern trees in northern land, new Witness Trees invokes the history of the Great Migration and establishes a spirit grove to keep the neighborhood safe. Reminiscent of the southern tradition of bottle trees, visitors are asked to record a sentiment or message of witness onto a reflective foil that is then tied to the tree branches. As fall gives way to winter, the grove glistens with light and reflection. Once spring returns, the witness trees will find a new home with residents of the South Side, where they will witness a new history.”

Francisco Quiñones (MArch II ’14) and his Mexico City–based Departamento del Distrito, co-founded with Nathan Friedman, have installed Miracles, Now at CAB’s Graham Foundation site. According to the CAB website, “Miracles, Now seeks opportunities of recovery and reinvention within the remains of urban and architectural projects constructed during the so-called Milagro Mexicano or ‘Mexican Miracle.’ This exceptional period of sustained economic growth between the 1940s and 1970s spurred the formation of Mexico’s modern identity, one specifically produced and marketed for a global audience.”

Surella Segú (LF ’18) and her Mexico City–based El Cielo have installed The Opportunity of Scarcity at CAB’s Graham Foundation site. The CAB website explains, “This installation serves as a ground to continuously recompose a vision formed by relating existing unconnected sites on the periphery of Mexico City through open spaces. For this installation, visitors are invited to rearrange the site models and add amenities, such as gardens, paths, benches, trees—made by artisans in Mexico—to reimagine urban landscape in Mexico City and offer inspiration for similar alternative futures for empty lots in Chicago.”

What if Washington DC were granted statehood? Preston Scott Cohen on designing a new American city-state

“Architecture for Statehood,” Preston Scott Cohen’s recent studio, tackles the timely question of what statehood would mean for Washington, DC, one of the most elegantly designed cities in the United States. Conceived in 1791 by Pierre Charles L’Enfant, a French-American military engineer, the urban plan for what was to be the new federal city positions the symbolic buildings of national power—including the White House and Capitol building—within a central core, with boulevards radiating out diagonally toward the fringes.

But while Washington is the seat of the country’s government—and a symbol of democracy throughout the world—its own people are denied one of their most basic democratic rights. The Constitution of the United States grants that each state has voting representation in both houses of Congress. But as the District of Columbia is not a state, there is no representation in Congress for its more than 700,000 citizens.

It’s a matter of justice. Washington must become a state. The slogan on DC’s license plate is indisputably accurate: ‘Taxation without Representation.’ It’s unconstitutional. It’s authoritarian. It’s undemocratic. This kind of design query and investigation is absolutely necessary.

The implications of this are substantial. And it begs some fundamental questions—sociopolitical, geographical, and architectural. “It raises so many consequential questions. This is my favorite studio hypothesis, ever. This is because of the way it intersects the urban, the architectural and the symbolic questions,” says Cohen. “The significance and importance of having it become a state is so palpable, so necessary. It’s a matter of justice. Washington must become a state. The slogan on DC’s license plate is indisputably accurate: ‘Taxation without Representation.’ It’s unconstitutional. It’s authoritarian. It’s undemocratic. This kind of design query and investigation is absolutely necessary. And the students are responding to it in very different ways.”

If Washington were to become a state, the introduction of new governing institutions and agencies that states require would bring about potentially dramatic changes to the city and the federal district, both spatially and symbolically. As a city-state, the renamed Washington, Douglass Commonwealth (in honor of Frederick Douglass) would be the seat of three systems of governance: city, state, and federal—which would, in turn, be multiplied threefold across the three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial.

The question that Cohen poses is how could this be articulated, architecturally. Currently, the L’Enfant plan places an overwhelming emphasis on the symbols of federal power. “What’s different about Washington is that it does not have a state government,” Cohen explains. “State governments have numerous institutions: departmental administrative buildings, archives, departments that deal with taxation, childcare, the elderly, and of course, the main governing bodies—the state courts, the capitol, and the executive branch and residence.’

But in Washington DC, the federal buildings, naturally, dominate. “This would have to be contested if the district were to gain statehood. For a start, there would need to be a basic re-weighting and reemphasis of official buildings—and the cityscape itself to some degree—in order to address this imbalance,” explains Cohen. “We envision these ideas because we’re interested in the implications as architects.” One potential solution is to imagine the new city-state as a cluster of mini cities—divided either by the four existing quadrants or by wards, reflecting how schools are governed locally. These, in turn, would each have their own, more robust, local governments, similar to those of the various counties or cities in the other states.

But this doesn’t solve the glaring architectural issue here: the fact that the city’s geographic center is also its symbolic center—and it is filled with federal buildings. “The new state will be a doughnut. The constitution for the new state (that has been voted on but not, of course, officially instituted) calls for carving out the iconic center of Washington as a strictly federal district inclusive only of the Mall and the main buildings of the federal government. Some of the federal government buildings will not be in this area, of course, ” Cohen says. “So this new state will have numerous federal buildings in it, but on state land. They will be leased by the state and taxed by the state, etc. So the overlay of state and federal will be very much like it is in other states where federal buildings populate states. Though we will still have a purely federal district, no one will hold residency there.”

How can Washington evolve into a place of its own, with its own state identity—one that isn’t subordinate to its beautifully designed federal core? The students are weighing several options, using specially created 3D digital modeling of the city that allows them to envisage overlays and interventions on the existing infrastructure. “You can quite literally undo the L’Enfant plan, subvert the hierarchies, you can interrupt L’Enfant’s diagonals—and some people are looking into that. If you want to break those diagonals, you’d have to tunnel or divert circulation—and that’s an interesting problem,” says Cohen.

“One idea is to adopt the ring of historic forts that sit on the periphery of the city—built to defend the Union during the Civil War—as symbols of state autonomy. We looked very intensely at many parts of the city. We’ve analyzed and interpreted its architecture extensively. I wanted to adopt the language of the urban fabric as a source for building new state institutional buildings. Not to always adopt strategies that are monumental, but rather to deploy anti-monumental strategies.”

Cohen emphasizes how important questions of social justice are for his students, and how statehood is fundamental to this. “The making of the state is to change DC, to have it not merely be what it is today—a city completely determined and governed by the federal government, without democratic representation. It’s really exciting to be dealing with a matter of social justice that’s so indisputably significant.”

Gareth Doherty Selected as CELA Regional Director

Gareth Doherty, director of the Master in Landscape Architecture Program and associate professor of landscape architecture, has been voted onto the board of the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture (CELA) . He will assume the role of the CELA director of Region 7, which includes Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, andVermont, and the provinces of New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Quebec.

“I first participated in a CELA conference, ‘Languages of Landscape Architecture,’ in June 2004 at Lincoln University in New Zealand. I greatly benefited from the comments received on my paper, not to mention the knowledge gained from the lectures and panels and the casual conversations over dinner, or on a bus. To this day, I remain friends with several of the participants from that conference way back in 2004. To me, this shows how effective CELA can be in providing a platform for sharing knowledge, ideas, and friendships,” recalls Doherty . “I’m thrilled to be part of CELA and to play a role in encouraging the sharing of new knowledge. As academics, we need to exchange ideas to thrive. And our institutions need CELA to thrive too.”

Doherty received his Doctor of Design degree from the GSD and his Master of Landscape Architecture and Certificate in Urban Design from the University of Pennsylvania. His teaching, research, and publications consider “people-centered issues alongside environmental and aesthetic concerns” through the framework of human ecology. His research also “advances methodological discussions on ethnography and participatory methods by asking how a socio-cultural perspective can inspire design innovations.”

Faculty- and Alumni-led Firms Named AN Interior Top 50 Architects 2021

AN Interior Magazine and the Architect’s Newspaper recently announced their “Top 50 Architects 2021,” and a number of GSD faculty- and alumni-led firms are among this year’s picks. Currently in its fourth iteration, the annual Top 50 list is chosen by editors to highlight design firms working in North America at the forefront of interior design and architecture.

According to AN Interior Magazine, “The list is intentionally diverse by firm size, reputation (many are quite young, while others have been leading the pack for decades), demographics, geographic location in North America (including Mexico and Canada), and type of work—everything from large public and institutional projects to single-family homes and installations.”

Faculty-led firms on the list include Dash Marshall , a multidisciplinary design studio co-founded by Design Critic in Architecture Ritchie Yao (MArch ’07), Bryan Boyer (MArch ’08), and Amy Yang. The practice, which is featured for the second year in a row, operates at the intersection of architecture, interiors, and civic strategy, believing that “architecture and interiors, buildings and cities can be better. Not only should they be more inspired and joyous, but they should help us live, work, and play more effectively.”

OMA New York , founded by Professor in Practice of Architecture and Urban Design Rem Koolhaas, was also recognized. Among the firm’s current projects is the 11th Street Bridge Park design, which is led by OMA partner Jason Long (MArch ’04) with associate Yusef Ali Dennis.

Other GSD-affiliated studios to make the list include:

- Architecture Research Office , led by Stephen Cassell (MArch ’92)

- BLDGS , led by David Yocum (MArch ’97) and Brian Bell (MArch ’97)

- FUSTER + Architects , founded by Dr. Nathaniel Fúster (MAUD ’96, DDes ’99)

- IwamotoScott Architecture , founded by Lisa Iwamoto (MArch ’93) and Craig Scott (MArch ’94)

- Kwong Von Glinow Design Office , founded by Lap Chi Kwong (MArch ’13) and Alison Von Glinow (MArch ’13)

- Low Design Office , founded by Ryan Bollom (MArch ’09) and DK Osseo-Asare (MArch ’09)

- Snøhetta , led by Alan Gordon (MArch ’82)

- Spiegel Aihara Workshop , founded by Daniel Spiegel (MArch ’08) and Megumi Aihara (MLA ’07)

- Stayner Architects , founded by Christian Stayner (MArch ’08)

- Utile Design , led by Matthew Littell (MArch ’97)

- WRNS Studio , founded by Bryan Shiles (MArch ’87)

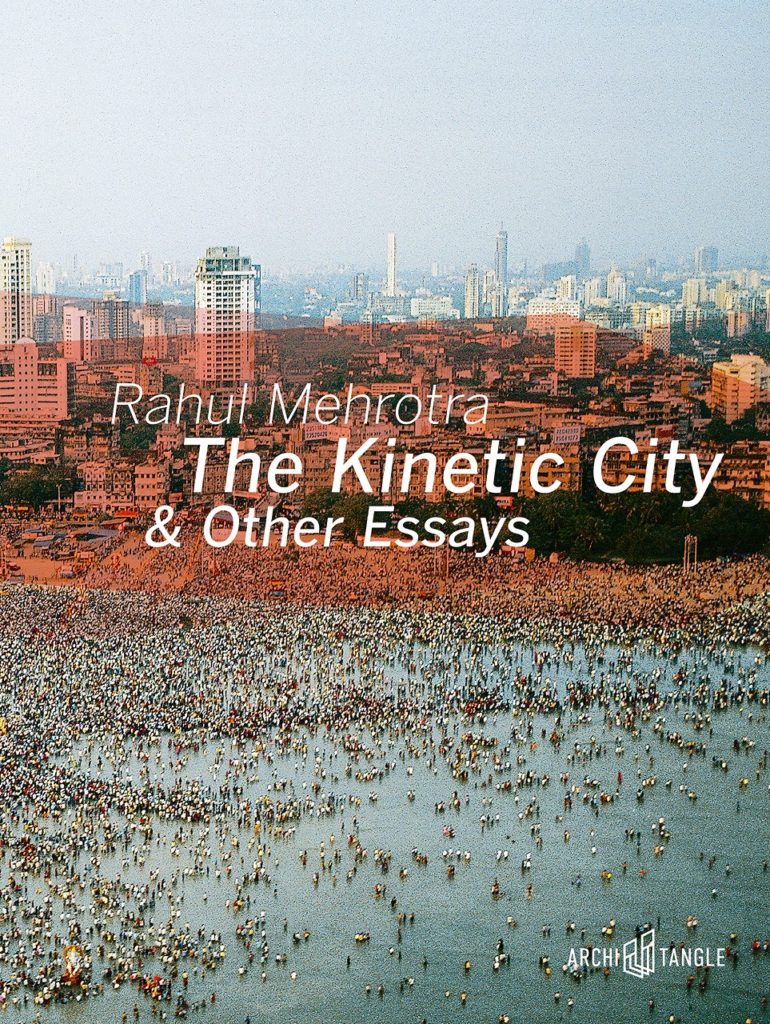

Excerpt from The Kinetic City & Other Essays: The Permanent and Ephemeral, by Rahul Mehrotra

The Kinetic City & Other Essays is the latest book from Rahul Mehrotra, Chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design and John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Published by ArchiTangle, the book presents a selection of Mehrotra’s writings from the last three decades and illustrates his long-term engagement with urbanism in India. Through the essays, Mehrotra describes how the emerging urban condition in India represents the “Kinetic City”—opposing the “Static City” of conventional city maps—by being “perceived, read, and mapped in terms of patterns of occupation and associative values attributed to space.”

On November 29, 2021 at 12:30pm ET, join Mehrotra on Zoom for a discussion of The Kinetic City & Other Essays as part of the Frances Loeb Library’s faculty colloquium series. Dean Sarah M. Whiting will moderate the event.

The Permanent and Ephemeral:

What Does This Mean for Urbanism?

by Rahul Mehrotra, originally published in The Kinetic City & Other Essays

Cities have largely been imagined by architects and planners as permanent entities – artefacts where architecture and planning are the central instruments for their manifestation. Today, this basic assumption stands challenged on three counts. Firstly, because of the massive scale of the “informalization” of cities where urban space is constructed and configured outside the formal purview of the State – a phenomenon that has engulfed the globe in the last four decades. Secondly, on account of the massive shifts in demography occurring around the world. The phenomenon of the movement of large groups of people across national boundaries as a result of political instability will only be accelerated by climate change, the depletixon and imbalance of natural resources or the rise of natural disasters. Lastly, the assumption that permanence is a default condition or the single instrument to imagine our cities is further complicated, albeit in positive ways, by the fact that in recent years, there has been an extraordinary intensification of pilgrimage practices as well as celebration and political congregations of all kinds globally, which have consequently translated into the need for larger and more frequently constructed temporal structures and settlements for hosting massive gatherings.

The combination of these factors should prompt us to rethink the assumption or notion of permanence in our response to the ever-shifting conditions of urbanism around the world. Like the “informalization” of the city, which results in temporary auto-constructed environments, natural disasters and changes in climatic conditions are also turning temporary shelters, extended with increasing frequency into camps or settlements, into holding strategies or short-term solutions.

There are numerous examples of such temporary occupation in response to natural catastrophes and environmental threats, such as those recently seen in the Philippines, Haiti and Chile, along with several other cases of temporary cities built in the context of disaster. Furthermore, political tensions in many places around the globe contribute to the displacement of people from their places of origin and fuel tremendous ecologies of refugee camps. The flux will continue to accelerate given the general inequity and imbalance of resources that have disrupted and brutally dislocated communities and nations across the globe. Extreme examples of humanitarian spaces hosting stateless persons and asylum seekers are the refugee camps located in Ivory Coast, which accommodate more than nine hundred thousand refugees, mostly from Liberia but also from other adjacent locations. However, the most striking cases are those of Dabaad in north-eastern Kenya, which accommodates almost five hundred thousand people, the Breidjing camps in Chad, home to two hundred thousand people, and several camps in Sri Lanka holding three hundred thousand people displaced during the decade-long civil war.

Startlingly, these camps only hold a small fraction of the forty-five million people who, according to the United Nations Commissioner for Refugees, are currently displaced around the world and living in temporary structures. At the other end of the spectrum, cultural and religious celebrations are also on the rise. Increasing in scale as well as frequency, they too lead to the erection of temporary structures within and outside urban areas.

Extreme examples of temporary religious cities are the ephemeral constructions set up for the Hajj, as well as a series of temporary cities constructed in India to host celebrations like the Durga Puja, Ganesh Chaturthi or Kumbh Mela – a religious pilgrimage, which according to official figures, draws congregations of over one hundred million people.

Extensive music festivals like Exit in Serbia, Coachella in California or Sziget in Budapest also lead to the construction of extended ephemeral settlements to house large groups of people together for short periods. Festivals range from relatively small gatherings, like the Burning Man in Nevada or Fuji Rock in Japan, where around forty thousand people gather to enjoy music and celebratory events, to three hundred fifty thousand people flocking to musical events like Glastonbury in England, Roskilde Festival in Denmark, and Werchter in Belgium.

These examples could be expanded to include many others, such as the temporary cities built on mining, oil drilling or forestry sites where natural resources are exploited. The Yanacocha mine in Peru, for example, employs over ten thousand people who live in temporary housing. Other mining communities like the Maritsa Iztok mines in Bulgaria, the Motru Coal mine in Romania, or the Chuquicamata, Salvador and Pelambres sites in the north of Chile generate completely different sorts of temporary settlements on account of the different time spans involved, adding a further degree of complexity. Here, large-scale operations have modified the topography of a landscape, albeit temporarily, on a territorial scale with the attendant environmental consequences.

The lifecycle of these temporary cities lasts as long as the resources being mined, and so have a known or predictable date of expiry. The operative question is thus: Can temporary landscapes play a critical “transitionary” role in this process of flux that the planet will experience evermore frequently? This contemporary condition, coupled with the rampant expansion of the influence of global capital and the colonization of land on the peripheries of cities, is locking the globe into unsustainable forms of urbanism, where fossil fuel dependence in combination with isolationist trends of gated communities for the rich are creating a polarity that will become harder to reverse.

So, while cities grow in the formal imagination of governments and patrons, the proliferation of the informal city is amplified in magnitude as never before! Is there a role for urban design in addressing these questions? Can we as architects and planners challenge the assumption that Permanence matters?

The city in flux is a global phenomenon. In several cities around the world, the postindustrial scenario has given rise to a new system where living and working have become extremely fragmented. The locations of jobs and places of living are no longer interrelated in the predictable fashion when job locations were centralized. In today’s networked economies, these patterns are not only fragmented but in flux and constantly reconfiguring.

This results in the fragmentation of the structure of the city itself and its form, where the notion of clear zoning or predictable and implementable land-use all break down into a much more multifaceted imagination of how the city is used and operates. It is an urbanism created by those outside the élite domains of the formal modernity of the State. It is what the Indian scholar Ravi Sundaram refers to as a “pirate” modernity that slips under the laws of the city to simply survive, without any conscious attempt at constructing a counter-culture.

Yet, this phenomenon of flux is critical to cities and nations connected to the global economy; however, the spaces thus created have been largely excluded from the cultural discourse on globalization, which focuses on élite domains of production in the city. They are spaces that have been below the radar of most architects and planners, who focus on the traditionally defined public realm. Yet within these confines, the very meaning of space is in flux and ever changing. It cannot only be defined as the city of the poor, nor can it be contained within the regular models of the formal and informal, and other such binaries. Rather it is a kinetic space where these models collapse into singular entities and where meanings are ever shifting and blurred.

The questions this raises are as follows: Can we design for this space as urban designers and planners? Can we design with a divided mind? Can other forms of organizations be embedded in our concept of the city and, if so, how do we recognize and embed these in the formal discourse on urban design? This is not an argument for making our cities temporary but rather one of recognizing the temporary as an integral part of the city and seeing whether it can be encompassed within urban design – in terms of urban form, public spaces, and governance structures.

Framing this phenomenon of flux under the rubric of “ephemeral urbanism” is perhaps to create a more inspirational category than the binary of the formal and informal city, for it implies the transitional rather than the transformative or the absolute. Furthermore, as designers we tend to observe and organize the world around us in binaries such as the rich and poor, the state and private enterprise, or the formal and informal city.

While these are productive as categories to describe the world, they do not seem to serve design operations productively because they force urban designers to occupy and advocate one or the other world articulated in the binary. Urban design, on the other hand, is about design synthesis and dissolving and resolving contestations through spatial arrangements.

So, what then is the role of urban design in this condition? Most certainly, this flux is the new normal. In addition, the spurts of growth and flux triggered by natural and political uncertainty are going to challenge our reading of the urban condition and the role of urban design. J. B. Jackson in his book Discovering the Vernacular Landscape (1984) and writing about North America highlighted the importance of what he called the third landscape – the landscape of cyclic events. He stressed that the first landscape was one of mobility: of the early colonial vernacular cultures, which preferred mobility, adaptability, and transitory qualities; of the short-lived tents and log cabins – a landscape that characterized North America before Jefferson’s classical farm villages appeared, he added.

These settlements of the decomposable (equivalents of which exist in every culture) are what Jackson brought to our attention. This mobile ephemeral landscape was replaced by another landscape, which “impressed upon us the notion that there can only be […] a landscape identified with a very static, very conservative social order” found in most of contemporary North American and European – and now perhaps Chinese – cityscapes. The people in this landscape, he argued, feel isolated from one another even though they work and live closely together. Thus, he implicitly argued for the “third” landscape where the ephemeral and the temporary can be instilled in the landscape of static objects to create richer social interaction. It is a landscape in flux and temporary, serving specific needs on a sometimes predictable timescale. The circus, the farmers’ market, and the festival, for example, are suddenly moments where different parts of society are made aware of their own existence within the urban system.

The ephemeral obviously has much to teach us about planning and design. In fact, the ephemeral city represents an entire surrogate urban ecology that grows and disappears on an often extremely tight, temporal scale. In short, this notion of the ephemeral as a productive category within the larger discourse on urbanism deserves serious consideration. For in reality, when cities are analyzed over large temporal spans, ephemerality emerges as an important condition in the life cycle of every built environment.

Peter Bishop and Lesley Williams recently asked: Given overwhelming evidence that cities are a complex overlay of buildings and activities that are, in one way or another, temporary, why have urbanists been so focused on permanence? The aim of broadening the rubric is a way of starting to assemble evidence that could give us some material to move toward a more open urbanism – open in the way Richard Sennett describes it, which in a city means being incomplete, errant, antagonistic, and non-linear.

The issues that could be negotiated in this form of urban practice are therefore as diverse as memory, geography, infrastructure, sanitation, public health governance, ecology, and urban form, albeit in some measure temporary. These parameters could unfold their projective potential, offering alternatives of how to embed softer but perhaps more robust systems in more permanent cities.

Andrea Branzi advises us on how to think of cities of the future. He suggests that we need to learn to implement reversibility, avoiding rigid solutions and definitive decisions. He also suggests approaches that allow space to be adjusted and reprogrammed with new activities not foreseen and not necessary planned.

Thus, architecture and urban design as a practice must acknowledge the need for re-examining permanent solutions as the only mode for the formulation of urban imaginaries, and instead imagine new protocols that are constantly reformulated, readapted, and re-projected in an iterative search for a temporary equilibrium that reacts to a permanent state of crises.

Furthermore, the growing attention that environmental and ecological issues have garnered in urban discourses, articulated through the anxiety surrounding the recent emergence of landscape as a model for urbanism, has evidenced that we need to evolve more nuanced discussions for the city and its urban form in the broadest sense. The physical structure of cities around the globe is evolving, morphing, mutating, and becoming more malleable, more fluid, and more open to change than the technology and social institutions that generated them.

Today, urban environments face ever-increasing flows of human movement, accelerating the frequency of natural disasters and iterative economic crises, which in the process modify streams of capital and their allocation as physical components of cities. As a consequence, urban settings are required to be more flexible in order to be better able to respond to, organize, and resist external and internal pressures. At a time in which change and the unexpected are omnipresent, urban attributes like reversibility and openness seem critical elements for thinking about the articulation of a more sustainable form of urban development.

Therefore, in contemporary urbanism around the world, it is becoming clearer that for cities to be sustainable, as both Saskia Sassen and Richard Sennett have pointed out, they also need to resemble and facilitate active fluxes in motion rather than be limited by static material configurations.

This expanded version of the practice of urbanism that embraces rubrics such as the “ephemeral” presents a compelling vision that enables us to better understand the blurred lines of contemporary urbanism – both spatial and temporary – and the agency of people in shaping spaces in urban society. Thus, to engage in this discussion, the exploration of temporary landscapes opens up a potent avenue for questioning permanence as a univocal solution for the urban conditions.

One could instead argue that the future of cities depends less (or completely, as in the case of the city beautiful movement) on the rearrangement of buildings and infrastructure and more on the ability of architects and urban designers to openly imagine more malleable, technological, material, social, and economic landscapes.

That is, to imagine a city form that recognizes and better handles the temporary and elastic nature of the contemporary and emergent built environment with more effective strategies for managing change as an essential element for the construction of the urban environment.

The challenge is then learning from these extreme conditions how to manage and negotiate different layers of the urban while accommodating emergent needs and the often largely neglected parts of urban society. The aspiration would then be to imagine a more flexible practice of architecture and planning more aligned with emergent realities that would enable us to deal with more complex scenarios than those of static, or stable environments constructed to create an illusion of permanence.

I would like to thank Felipe Vera and acknowledge the many essays we have written together on the subject of Ephemeral Urbanism. Naturally those have influenced this essay. And to Ricky Burdett for the development of some of these ideas.

Faculty-led CO-G Wins WS Development’s Inaugural Design Competition for Public Art

CO-G , the design studio led by Design Critic in Architecture Elle Gerdeman, is a winner of WS Development ’s new biennial juried competition, Design Seaport . Emerging practices were invited to submit designs for public art that “engages, inspires, and unites” the fast-growing Boston neighborhood.

The puffy, cobalt-blue installation—incorporating recycled denim and foam—plays on Gerdeman’s early career in fashion. An interest in materiality, tectonic assemblies, maintenance, construction, and weathering finds its way into all of her work.

Read more about the project on the Interior Design website.