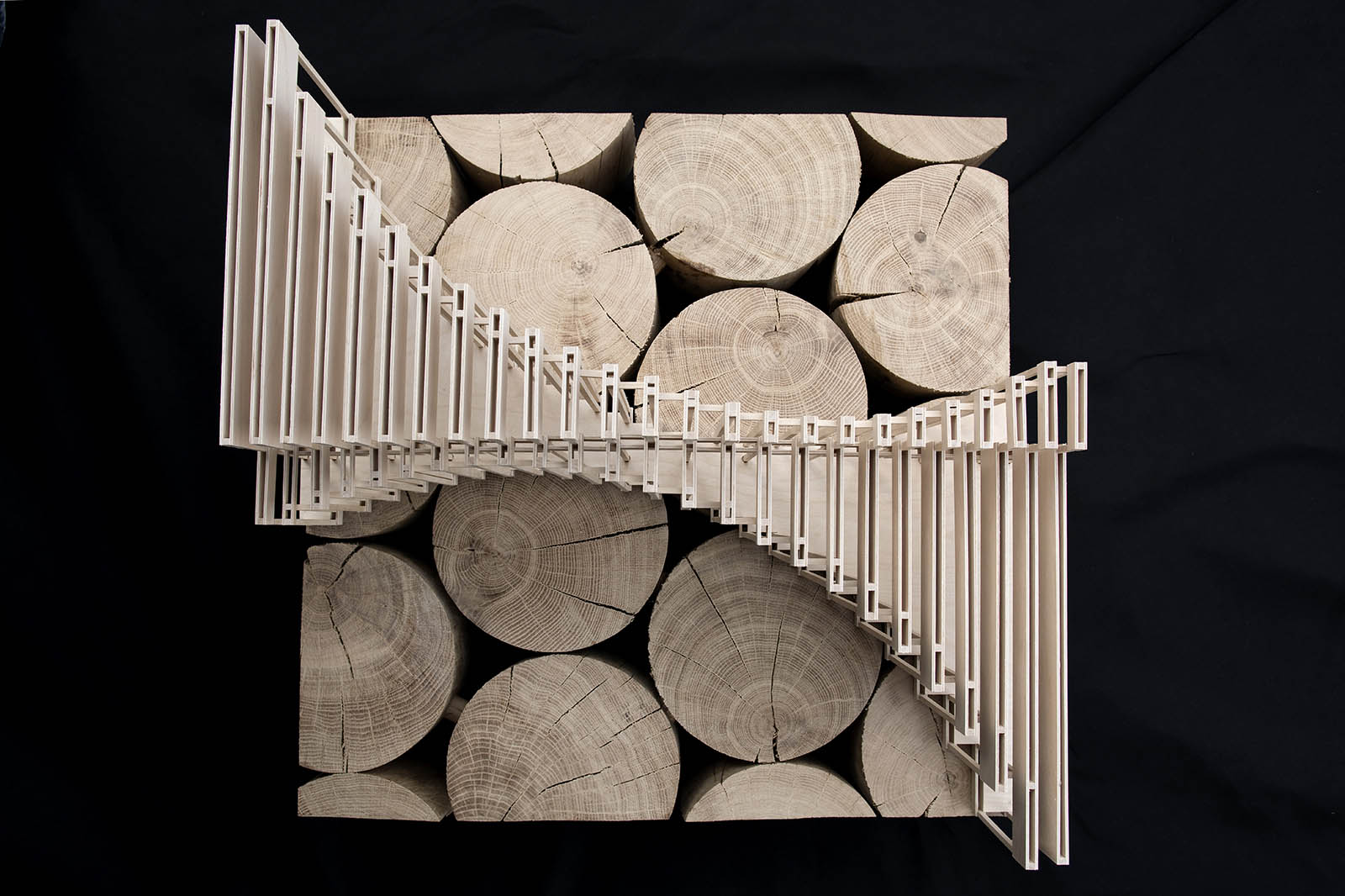

In 2004, Norwegian architect Beate Hølmebakk co-founded Manthey Kula with Per Tamsen, and the practice has since become known for small but beguiling architectural interventions that play with form and context in unexpected ways. From a heavy steel restroom overlooking Norway’s scenic Moskenes Island, to a transparent ferry port with a distinctive, U-shaped roof–both of which were nominated for the Mies van der Rohe European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture–their work transforms humble briefs into arresting shapes uniquely suited to their site and purpose.

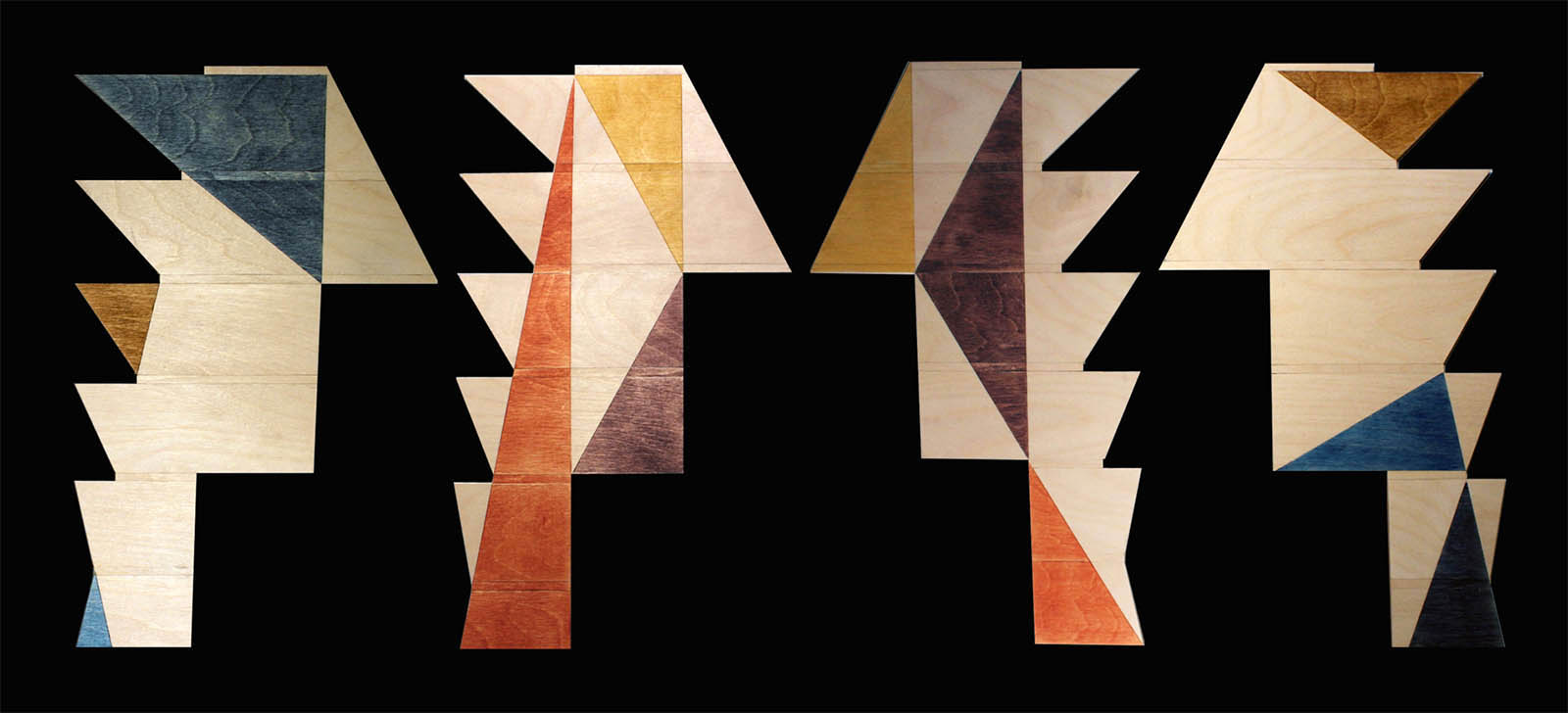

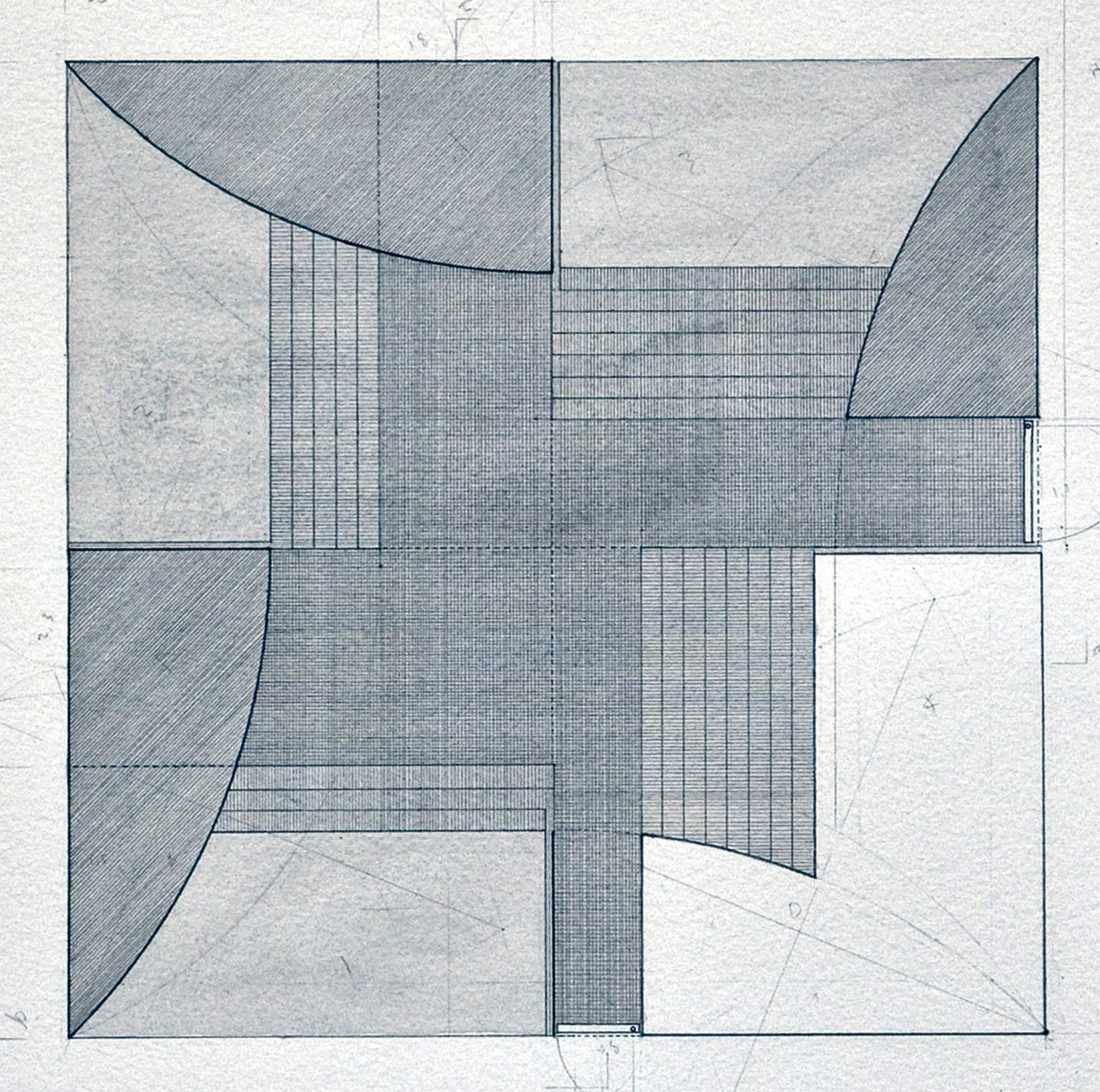

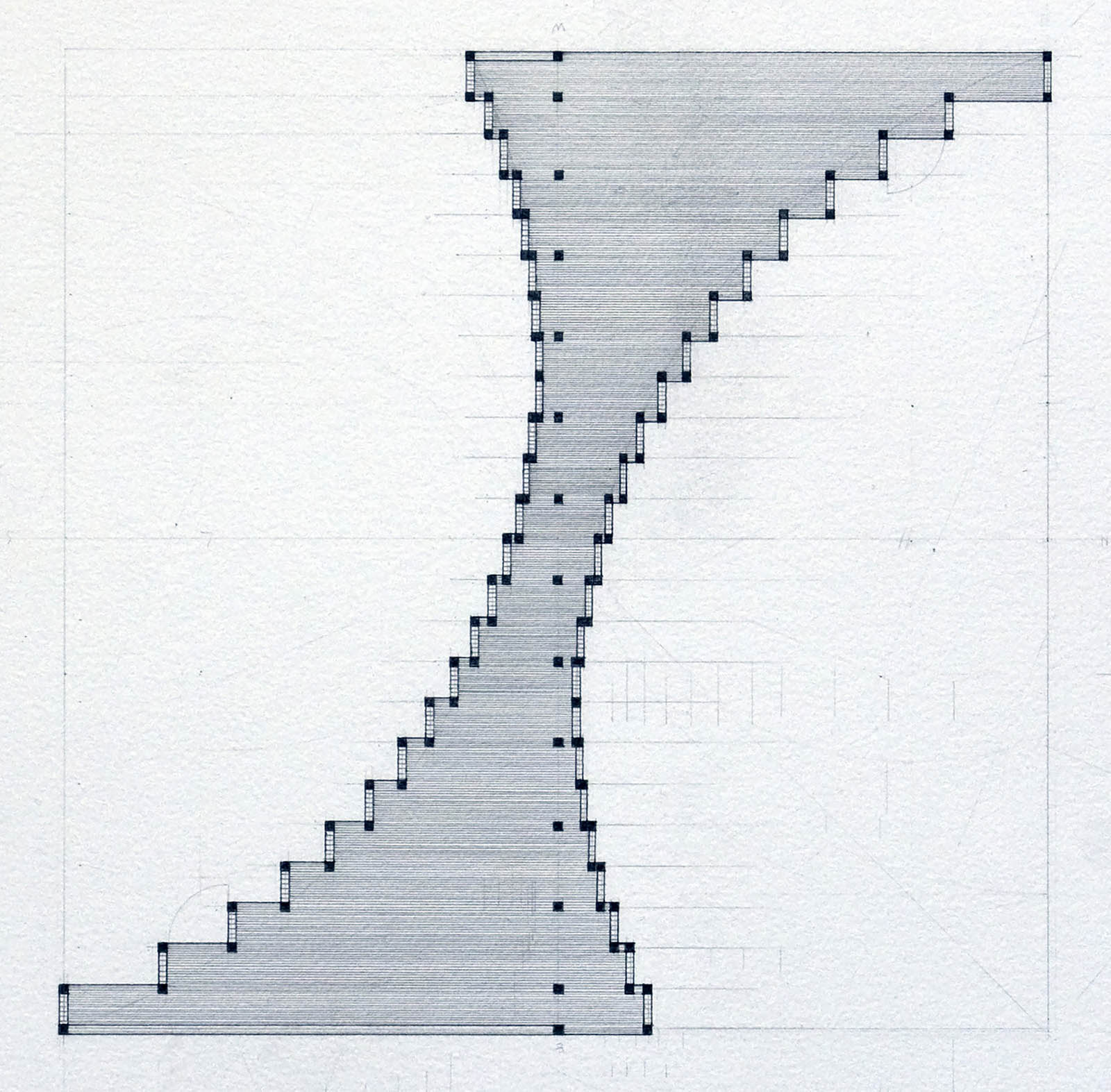

A significant part of Beate’s practice are her “paper projects”, works that are deeply considered but never intended to be built. In Virginia, a series of houses were conceived around the lives of four female literary characters; in Archipelago, the stories of five people living in isolation on remote islands were used to develop a set of architectural forms. Through these speculative explorations, Manthey Kula pushes the boundaries of architecture as a medium for exploring fictional states of mind, body and form.

Today, Holmebakk is a professor of form, theory and history at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design. Ahead of her lecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, she discusses her philosophy and approach to both these types of projects, explaining how she measures the success of an idea and why architecture needs to “dare to have character”.

How do the two elements of your practice, the built and unbuilt works, relate to each other?

With the built work, we’re concerned with the site: how the building can make it more interesting, solve its problems or foreground its most beautiful elements. The unbuilt projects don’t have a site, so the internal story becomes the context. There’s always a narrative and an existential theme in the paper projects, which the architecture is built around. Whether a project is ultimately built or unbuilt, we’re interested in sculptural forms that have character. What ignites the form varies, but how we develop it is similar; it’s like the difference between prose and poetry.

Do you think of architecture as an artistic medium?

Absolutely. When we work as architects, we have a lot of measurable constraints and we’re trained to be logical in the way we develop a project, to show there’s a reason for our choices. But it’s the mix of personal, irrational elements that dictates if a project is going to be this or that. In the end, it’s about feeling trusted and believing in your own ideas.

At its best, I think architecture is a state of mind. There’s something about the experience of space that has been with us since we were small–a basic understanding that has to do with our personal story. I believe that’s an important factor in the way we work: the search for something eternal in our experience that we’re trying to recreate. When you enter a building or a space that is well made, it’s an existential experience.

Without rational parameters–for example with your paper works–how do you measure success?

In our paper works we create self-imposed constraints; it’s hard to develop anything without any limitations. In the beginning, it was more about trying to find a theme that could be dealt with architecturally, whether it was the relationship between people or between inside and outside. With the Virginia project, the architecture developed from personal interpretations of literary texts. Later on, for example with the Archipelago project, we imposed specific, almost mathematical constraints–for example, scales and measurements that were in use during the time when these historical protagonists lived.

You’ve said in the past that you don’t particularly like terms such as “user friendly” or “humane” as architectural aspirations. Why is that?

If you want a project that people can relate to, it has to have a core that people can agree or disagree with. It has to dare to have character. I think it would be a mistake to overlook the complexities that exist in our discipline and attempt to make architecture digestible for everyone. There are so many nuances in the world, so if one is only seeking a norm for what is “humane” or “user-friendly” in architecture, that would be incredibly boring.

Interview by Debika Ray. Images courtesy Manthey Kula.