Wind blows hard over the bluff as huge waves roll in from the horizon, crashing finally, thunderously on the sea stacks and rocks below. An unending acoustic flow and rhythm, deep and ever-present, plays over the fields and hedgerows. Lines of 100-year-old cypress trees reach back from the cliffs. Graying redwood-sided houses poise unobtrusively behind the hedgerows out of the wind. Their roof slopes, like the branches protecting them, seem to give the airflow material form.

All of this hardly conjures the image of suburbia. But, bound by Highway 101 to the great conurbation around San Francisco Bay, carved with cul-de-sacs, and sprinkled with single-family houses, the Sea Ranch is very much a bedroom community. It originated in the early 1960s as a developer-driven project, a large real-estate venture aiming to settle nearly 2,000 families on 5,000 acres of land. But from the beginning, its designers envisioned it as something different. Lawrence Halprin, the Harvard Graduate School of Design-trained landscape architect who drew up its first master plan, called it “a new kind of Utopia.” He envisioned the Sea Ranch as an “experiment in ecological planning” with “place as a generator of community design.” The architectural team (Charles Moore, William Turnbull, Donlyn Lyndon, Richard Whitaker, and Joseph Esherick) that planned the 10-mile stretch of Pacific coast and designed its first buildings formed a community of their own. “The experience of the Sea Ranch began to infiltrate our lives,” Halprin recalls. They camped on the site with their families. They brought their students to study it. They ran workshops with designers, dancers, and actors on the beach, building driftwood “villages” and weaving myths around the idea of community. Most of them built houses for themselves at the Sea Ranch.

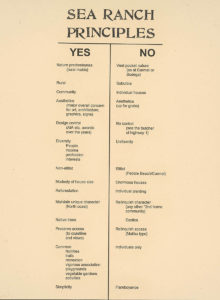

The special care that these first settlers (as they thought of themselves) took with the land led them to establish deeply felt principles for the development. They wanted, first of all, to avoid building another copy of “suburbia” along the Pacific coast, but they also wanted to keep the houses affordable and maintain much of the place as commons, freely accessible to everyone. They proposed arranging the houses in “farm-like clusters” and using compatible materials, fencing, and vegetation to bind them into neighborly groups. This required careful subdivision of the land and minutely scripted rules for engaging it—no mansions, no grass lawns, no visible antennas, no visible clotheslines, no reflective cladding, all exterior surfaces in shades of gray or brown, and so on. The development’s Declaration of Restrictions, Covenants and Conditions, first published in 1965, specified these and other minutiae, but it was most emphatic about preserving the natural character of the site. “The purpose of this declaration,” it says, “is to perpetuate… the rich variety of this rugged costal, pastoral, and forested environment for the benefit of all who acquire property within the Sea Ranch.” A Design Committee would oversee many of the rules to assure that the original spirit of place would persist.

Although these rules have remained virtually unchanged, the Sea Ranch has not fulfilled its originators’ grandest expectations with regard to community. Much of the landscape has been preserved intact, but, as Halprin lamented in the early 2000s, “succeeding waves of people flawed the experience.” Some of the houses have gotten too big and isolated. Some of the later developments gravitated into standard suburban patterns that claim views for individual families and exclusive access to common land that should have been shared. (And prices have gone up: Original houses and condo units sell for well over $1,000,000, and a typical lot goes for $500,000). Above all, an authentic community failed to develop. Halprin acknowledged that the Sea Ranch did not have “a functional base” upon which a community could form. Although there was a common love for the place and shared aspirations for it, recreation, not work, was its foundation and has remained so. And strong feelings for the place have sometimes led to disagreements. Halprin acknowledges that “self-governance at the Sea Ranch has sometimes been difficult… rancorous, shrill.” Despite its unquestionable beauty, the Sea Ranch, he says, never formed a viable center to hold it together.

As one of the twentieth century’s most vital experiments in communal, ecological living, the Sea Ranch stands as an open question: “How can we live together?” This semester, in a studio run by Iñaki Abalos, thirteen Harvard architecture students are reconsidering this question. The challenge, Abalos explains, is “one of the deepest paradoxes of our time.” The students’ task is to design a cluster of modest houses “where co-living and co-working are the basis of a new social structure.” They are questioning an all-too-typical style of development, Abalos says, in which “the family has to be in limbo, protected from the city, with the car as their connection.” It is sometimes “a beautiful limbo,” he admits, but hardly conducive to the construction of vital community. Instead, Abalos asks the students “to construct a new ecology of humans and non-humans… an alternative commune, a co-living form that revises and updates the idea of a collective Palace.” To start, they critically examined American suburban development, considering its “disgraces” (particularly given the recent environmental tragedies of fire and flood that have destroyed so many lives in the suburbs, Abalos points out) but also investigating some of its most innovative manifestations. They analyzed case studies and visited experimental suburbs near Boston—Frederick Law Olmsted’s failed development of World’s End in Hingham, and the old company town of North Easton, with its civic buildings by H. H. Richardson and well-built workers’ housing. The studio group also traveled to the West Coast to visit the Sea Ranch and an exhibition about it at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Sea Ranch. Architecture, Environment and Idealism.

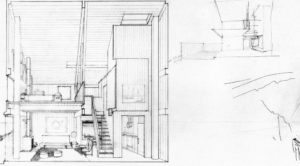

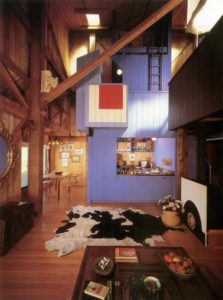

Guiding the studio is an idea of “idiorrhythmy,” taken from Roland Barthes’ 1977 book How to Live Together: Novelistic Simulations of Some Everyday Spaces. The term conveys an understanding of harmonious conviviality in which individuals live according to their own patterns while accepting the living patterns of others. Barthes suggests that these interrelated rhythms develop communal bonds while assuring individual equanimity. The studio case studies and site visits seek architectural prototypes for this. At the Sea Ranch, students visited one such example: Condominium One, designed by Moore, Lyndon, Whitaker and Turnbull (MLTW) in 1965. One of the first constructions in the development, and certainly its best known, it exemplifies the experimental, ideological vision of the Sea Ranch design team. Condominium One resonates beautifully with the vast windblown landscape, its sloping roof-forms and weathered wood cladding offering an almost iconic rendition of environmental sympathy. It also binds people together. Built with “the footprint of a monastery,” as Abalos describes it, its ten conjoined dwelling units cluster around a sheltered court. Inside, each unit contains two small aedicules that hold or frame particular activities—sleeping, cooking, conversing—so that even within family settings individual rhythms play out in their own domains.

Charles Moore owned Unit 9 of Condominium One for nearly thirty years, frequently re-painting walls, adjusting furniture, and adding decorative objects. The result was a highly idiosyncratic home, a manifestation of his own patterns of living within the collective. Not far from Condominium One, another idiorrhythmic prototype merges with the vegetation above the sea cliffs. Joseph Esherick & Associates built clusters of “Hedgerow Houses” protected by the wind-sculpted cypresses that ranchers had planted fifty years before. Their roofs mimic the sweep of the branches; dark wood cladding blends with the shadowed understory of the trees. Each house in the cluster defers to the others, sharing views and common space. The designers of the Sea Ranch hoped that in these clusters of homes, patterns of individual actions would bind with the complimentary life patterns of others and with the natural vitality of the site to shape a communal, ecological symphony.

While they may have fallen short of their highest aspirations, the legacy of the Sea Ranch designers continues in the research of Harvard’s graduate students. Perhaps, like Lawrence Halprin and his team nearly sixty years ago, braced against the wind, looking over the crashing waves toward the western horizon, these new designers will discover “an alternative to the suburbs capable of satisfying contemporary needs and aspirations.” Although this may have been merely the initial call of Professor Iñaki Abalos’s studio brief, after weeks of research the students have made it their own goal. Returning from California they will develop new models for co-living shaped by the past but also, Abalos explains, “connected with a broader sense of time.”

Images courtesy of the Lawrence Halprin Collection; The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania; University of California, Berkeley; and San Francisco Modern Museum of Art © Lawrence Halprin

Continue reading about the course How to Live Together, the Department of Architecture’s 2019 course offerings or Iñaki Abalos’ research. Student projects related to this course will be available after May 1, 2019.