Mohsen Mostafavi’s deanship has been booked-ended by publications: The first was Ecological Urbanism and the last, or almost the last, was Platform 11: Setting the Table. The latter now sets the table for the new Chair of the Architecture program and the new Dean of Harvard Graduate School of Design. Between the two books, there have been approximately 90 publications produced during Dean Mostafavi’s tenure, ranging from expansive studies and scholarly research to internal registrations of student and faculty work at the school. There have been, for example, 11 Platform publications, which are annual reviews of projects across the spread of the GSD’s various programs. These platforms are proposals and ledges or viewing points into the pedagogical work underway in Gund Hall trays and classrooms.

The arc between Ecological Urbanism and Platform 11: Setting the Table has been central to Mohsen’s leadership. It maps his interests in the scope of contemporary urbanisms and reflects both his administrative and creative attention to the intellectual life of the school. It also encompasses changes made at Harvard under Drew Faust’s presidency, and the earliest publications were inaugurated in the shaky period following the 2008 global financial crises. The publications are a series of linked analogs for how the GSD might look if it took the form of a book. Ranging from periodic journals to 700-page volumes, each book is meticulously designed, filled with drawings and images, attentive to civic responsibilities, diversity, and academic integrity, supportive of evidence-based and theoretical scholarship that fosters broad spectrum inquiries, and funded. They are, above all, hospitable to the professions they call upon.

What of the 88 other publications? Mohsen made a diagram for me. He first drew a circle and put the GSD inside it. A solar system, so to speak. From this center many arrows radiate. One arrow goes to a circle saying “Platform books,” another to a circle for “journals,” referring to the Harvard Design Magazine, among others (the last issue under his watch is called “Inside Scoop” and is due out in the spring of 2019). There are arrows to circles for New Geographies—#10, entitled “Fallow,” is coming out later this month—and “Polemics,” for books on ethics and politics. There are 26 publications in the “Studio Report” series including three on Jakarta, Manila, and Kuala Lumpur regarding Asia’s commitment to larger projects, and three transitional studies on China, published together as Christopher C. M. Lee’s Common Frameworks: Rethinking the Developmental City in China. “Transforming Omishima,” was a collaboration between GSD Studio Abroad in Tokyo with Toyo Ito and his students to restore the spiritual presence of Omishima. There are also studies of architects such as Kenzō Tange and John Portman. And more.

The research resulting from many of the projects, which the books are distillations of, has been compiled and archived in the Dean’s office. The publications thus register a decade of the GSD’s collective research into deep urbanism. They are not ends in themselves. As Mohsen wrote in Ethics of the Urban: “It is in part the responsibility of the designer to imagine alternative ways of actualizing the relationship between various dimensions of society. To understand both the given condition of things and their potential transformation, however, requires constant collaborations and reciprocities between the users and the designer.” Another manifestation of collective intellectual hospitality.

Mohsen mentioned, in an interview, that when he became Dean in 2008 his first action was to reorganize the program offices—Landscape Architecture, Architecture, Urban Design, Planning—to bring them closer to each other. His next action was to reorganize the school in relation to the University, and his third was to point the GSD collectively toward global engagement with the pressing issues of our day. He introduced this third initiative through Ecological Urbanism. Urbanism—urban design and urban planning—is often subordinated to architecture programs in large schools. The first degree program in Urban Design in the world was instituted at the GSD by Josep Lluís Sert, a Spanish architect and city planner who was the last president of CIAM and Dean of the GSD from 1953-1969. This legacy plus the contemporary urgency of global crises—climate change, migrations, political turmoil, urban infrastructures and housing—prompted Mohsen, in concert with members of the GSD faculty and colleagues both in and outside Harvard, to orient the school toward a different urbanism, now aligned with the ecological.

“In… the urban,” he wrote, “as a physical artifact, is the built representation not just of our creative and technical knowledge but also of our societal values.” Citing Chantal Mouffe’s concept of “agonistic pluralism,” Mohsen argued that the urban artifact provides a “crucial setting for promoting democratic values.” The ecological part of the project refers not only to the impact of climate change but also to the vast networks of energy, transportation, and financial systems that continue to expand and diversify definitions of urban and rural landscapes, political borders, peoples and the academic assemblies that shape practices such as architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning. The ecological urbanism initiative eventually altered, in particular, the DNA of the Landscape Architecture program at Harvard and enlisted other programs in large-scale, cross-disciplinary studies of cities, architecture, infrastructures, technological and socio-political forces. Landscape architecture, in Mohsen’s words, now negotiates “an increasingly important zone between architecture and urbanism.” To accommodate new subject matter arising from the GSD’s exposure and participation in the “global,” other degree programs—the Doctor of Design and Master of Design programs—were redirected, and several new programs were created. In Instigations: Engaging Architecture Landscape and the City, Mohsen writes that the “academy must be at the forefront of new ideas for rethinking our habitus, the built environment” and that “[s]uch a task cannot be achieved without rethinking the roles, responsibilities, and potential impact of each discipline.” Such a task depended on an unprecedented commitment of the GSD to design research. This concentrated shift in orientation resonated through architecture, landscape architecture, and urbanist programs and practices everywhere.

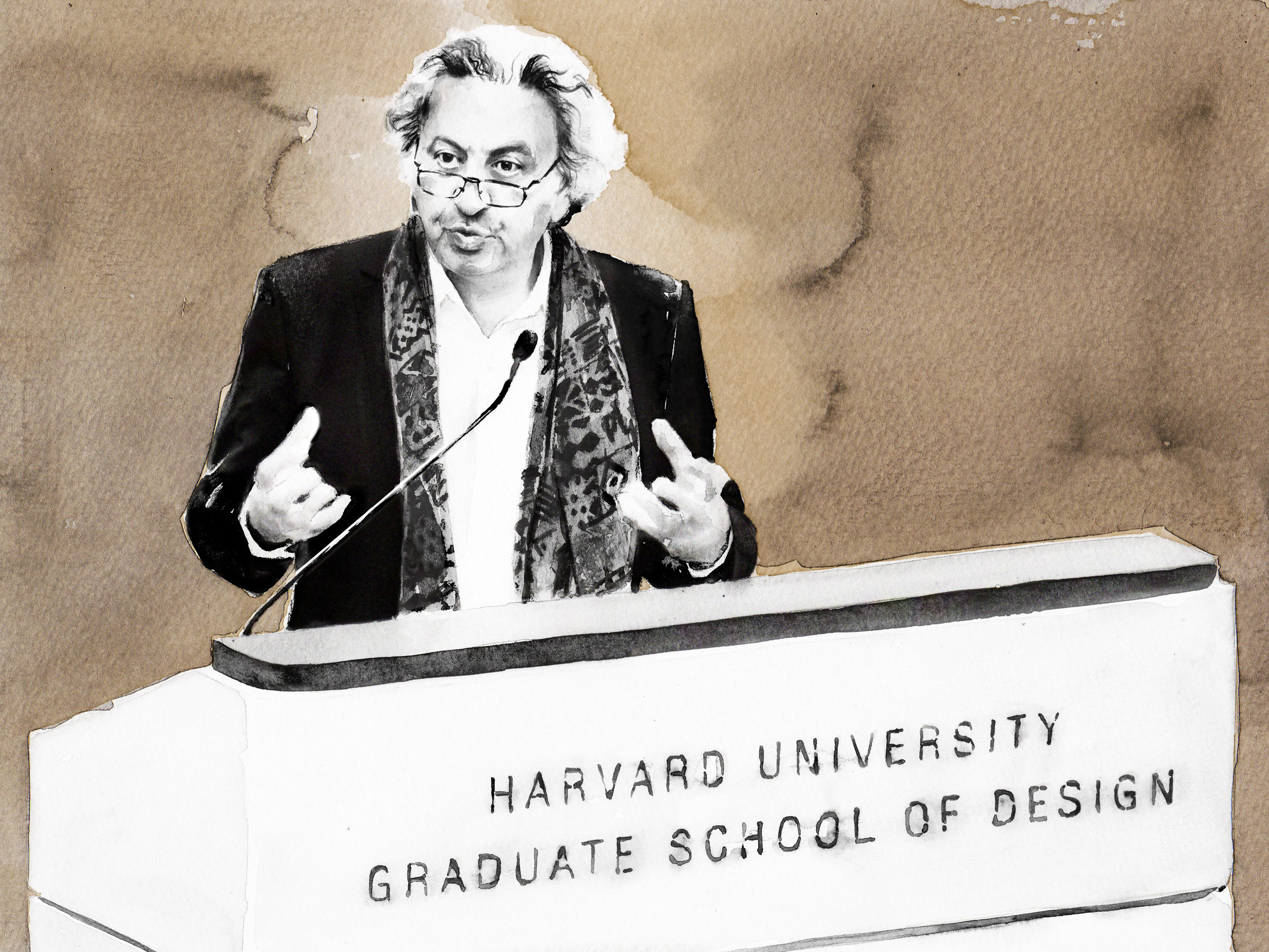

There are different kinds of deans. Some remain in the background of a school, tending to its financial and social well-being. Others, like Mohsen, enact ideas about the overall intellectual vitality of a school as part of their administrative work. Deans are custodians of the standing of their school in relation to other schools, but the GSD, like Harvard, is an ocean liner, as I have heard people say. It is a large machine that keeps its engines in top condition and goes ever forward. Mohsen’s stewardship thus did not directly or specifically concern the status of the school. Instead, he used his Deanship, and the GSD’s already strong presence, to ask what the school was going to do, what the school could and should do, for Harvard on the one hand, and in response to the issues of its time on the other. What Mohsen meant by bringing the GSD to the attention of the University was to “make itself useful” to Harvard at large.

There are different kinds of deans. Some remain in the background of a school, tending to its financial and social well-being. Others, like Mohsen, enact ideas about the overall intellectual vitality of a school as part of their administrative work. Deans are custodians of the standing of their school in relation to other schools, but the GSD, like Harvard, is an ocean liner, as I have heard people say. It is a large machine that keeps its engines in top condition and goes ever forward. Mohsen’s stewardship thus did not directly or specifically concern the status of the school. Instead, he used his Deanship, and the GSD’s already strong presence, to ask what the school was going to do, what the school could and should do, for Harvard on the one hand, and in response to the issues of its time on the other. What Mohsen meant by bringing the GSD to the attention of the University was to “make itself useful” to Harvard at large.

When Mohsen returned to the GSD to become its Dean, he said it felt like coming home. He had been a professor in the school earlier, before he became Chairman of the Architectural Association in London and, later, Dean of the School of Architecture at Cornell University. Being useful to Harvard was, thus, an extension of Mohsen’s familiarity with the university. He felt that the GSD had become insular, which can happen to professional schools in large research universities. Further, Harvard, under President Faust, was interested in revitalizing the arts, diversifying the university, increasing financial aid for students and building common spaces for the campus community. There were, as a result, numerous joint projects with University, including the Science Center Plaza, which became an event space, and a new Student Center. Mohsen often facilitated relationships with other departments, centers, and institutes in the university, and served on multiple boards and committees.

Amidst all of Mohsen’s ambitious changes there was a conscious decision not to grow the architecture program per se. Architecture, he says, is the mothership of the school, which it is. Instead he re-balanced the other departments and programs around the nucleus of the architecture program. He encouraged the participation of all the departments in the life of the school, including the Ph.D. program, which is an integral part of the GSD but officially belongs to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. As with other universities and colleges across the United States, the GSD, and Harvard at large, has increasingly been charged with hiring diverse faculty and admitting a more diverse body of students. Mohsen has supported these mandates and worked with the University to change admission and hiring systems. Along with other associates and faculty, he has also increased the role of junior faculty, who represent important generational shifts in architectural and landscape thinking. Mohsen said that he is most proud, both personally and professionally, of his role in fostering a series of conversations and interactions that allowed the school to engage, with intellectual acuity and imagination, with people and places in complex environments throughout the world. And conversely, in the process, to continuously welcome people from many different disciplines and interests into the GSD. Urbanism is a form of hospitality, as is the ecological. Hospitality is not an easy thing to accomplish. It signifies a meaningful relationship to culture and cultures. Various philosophers have argued that this concept, in multifaceted ways, has been worked into science, disciplines, aesthetics, concepts of “open cities,” and ethics. Culture, made manifest in the many forms of hospitality that Mohsen has facilitated—conversations, artifacts, research, design, administrative styles, publications, exchanges, common ground—can transcend socio-political boundaries and offer new horizons. That kind of Dean.

Dr. Catherine Ingraham is Lecturer in Architecture at Harvard Graduate School of Design. She has lectured and published widely in architecture and architectural history and theory. She was an editor, with Michael Hays and Alicia Kennedy, of the critical journal Assemblage and is currently a Professor of Architecture in the Graduate Architecture program at Pratt Institute in New York City, a program which she chaired from 1999-2005. Her publications include Architecture, Animal, Human (Routledge Press, London 2006) and Architecture and the Burdens of Linearity (Yale University Press, New Haven 1998).