UPDATE, 10/18/19: The American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) has awarded the project Mobility As Equality: Building Towards the Olympic/ Post-Olympic LA Transit (profiled below) the 2019 Award of Excellence in the Analysis and Planning Category of its annual ASLA Student Awards. Read more about the project and its design team (Amanda Ton, WeiHsiang Chao, Xin Qian) in the following feature.

There’s a movement underway in Los Angeles to rediscover public spaces, to reconsider the city’s focus on cars, freeways, and single-family homes, and to engage public transit as an integral rather than supplementary urban element. It’s a moment of reckoning that’s being fueled, in part, by the largest infrastructure investment in United States history: In passing Measure M in 2016, Los Angeles approved an additional sales tax that will provide $120 billion for new rail lines in the LA Metro system by 2047.

In other words, Angelenos voted to tax themselves in order to fund and improve the city’s public transit. It’s a noteworthy gesture from the “car capital” of the country, an acknowledgment that a growing metropolis needs good public transit. Rather than continual expansion at its edges, LA is dedicated to strengthening its urban core.

In 2016, in the glow of Measure M and its milder predecessor, Measure R—which Measure M extends in perpetuity—then–Los Angeles Times architecture critic (now LA’s chief design officer) Christopher Hawthorne declared that the city is on the threshold of being the “Third LA.” According to Hawthorne, the First LA spanned the late 1800s through World War II, and the Second LA, with its stereotypes of car culture and suburban sprawl, covered the rest of the 20th century.

The Third LA is interested in the model of a shared city, with the future of its streets, its public transit, and its people forming the heart of this equation. The city has reignited the pioneering, growth-minded spirit of the First LA and has grown newly interested in the physical infrastructure, especially the streets, of the Second LA. Many of the concerns inherent to the Third LA center on public space, including those many streets and highways, as the city grows and changes and as it finds itself needing to accommodate more people.

Yet even as LA progresses toward a more transit-oriented future, it is simultaneously a battleground for private-sector technologies like ride- and bike-share companies and autonomous vehicles. And accompanying the city’s growth are the familiar problems of higher cost of living, displacement, and economic anxiety.

In the spring of 2019, Future of Streets in Los Angeles—Andres Sevtsuk’s Harvard Graduate School of Design studio—examined how LA might maximize the opportunities at stake. The studio sought strategies to creatively optimize investment in public transit in an increasingly hot market for private-sector services. How can technology complement, rather than compete with, public transit? And, as LA reshapes itself, can it improve equity, sustainability, and quality of life as it aggressively redevelops its transit systems?

Sevtsuk and students met with stakeholders across the city. They held closed-door meetings with the Department of City Planning, LA Metro, and other agencies. They workshopped and codeveloped proposals with members of the LA community, and experimented with LA’s terrain with help from Renault-Nissan’s Future Lab and Ford’s Smart Mobility Team. The ensuing dialogue and proposals get to the heart of how Americans view transit decisions and civic investment, drawing instructive contrasts between simple, shovel-ready fixes and visionary, fundamental transformation.

Streets Are for People

Sevtsuk focused the early weeks of Future of Streets in Los Angeles on LA’s historical and contemporary contexts, in which roadways and highways loom large. From this, studio members Sunmee Lee and Yuebin Dong asked: With such an expansive, interconnected system of highways, and one that’s so ingrained in Angelenos’ minds, why not start our current transit conversations there?

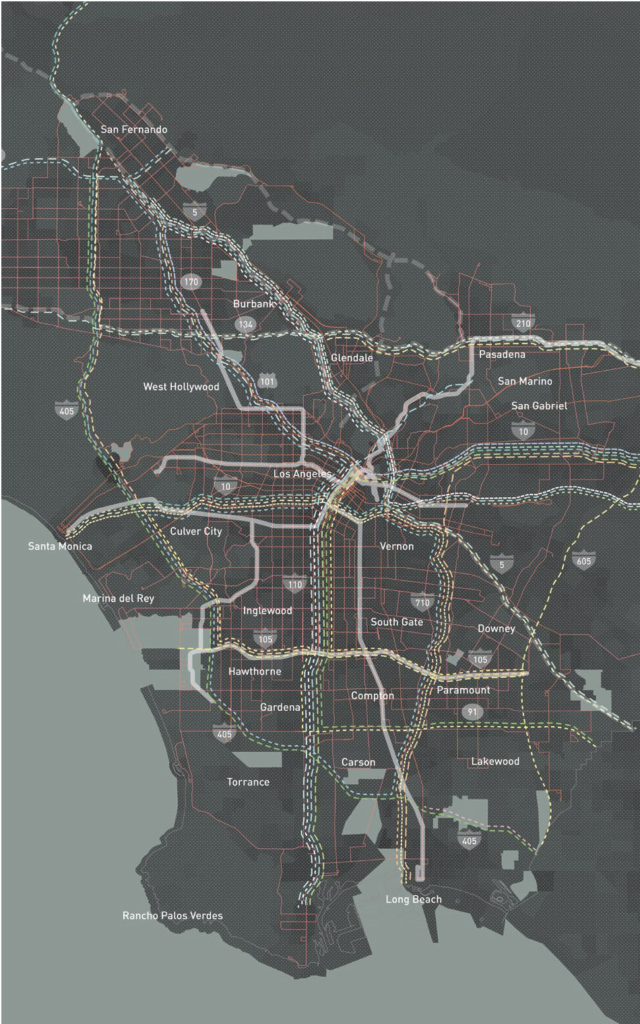

Dong and Lee’s proposal, “Highways as Public Transit Infrastructure,” reimagines the Los Angeles County highway system as the backbone of a public-transit network. The project would repurpose HOV-Express lanes on area highways as a series of bus stations, with local “Micro-Dash” connector shuttles to ease transfers between the new, highway-based stations and existing Metro hubs, ultimately creating almost door-to-door commutes. New transit stations along the highway would gradually be enhanced with community-focused amenities, resolving a long-standing frustration over the often uncomfortable, neglected bus stations that LA residents are accustomed to.

The proposal aims to expand the advantages of the already existing system, as well as the new Measure M budget, to more and more people. Dong and Lee crunched the numbers, looking at demographic, financial, and traffic-flow data. As an alternative to the purely rail-focused investments of Measure M, their highway-based bus system would achieve 5.4 times more new transit coverage for LA County and its residents, and would reach 3.5 times more low-income households—all under the same budget as Measure M’s current plan.

Dong and Lee seek to promote both equitable and efficient mobility by fundamentally reconsidering how the highway is used. In bringing transit access to more people—especially low-income families—they also seek restorative justice, addressing the aggressive red-lining and dismantling of neighborhoods that accompanied the highway boom of the mid-1900s. “Since the automobile era began, transportation injustice in LA has been reinforced,” Dong and Lee write. “Our proposal suggests bringing public transit to the places in most need, while avoiding the displacement of existing communities.”

Part of their vision springs from a workshop the studio conducted in February in LA, alongside the Renault-Nissan Future Lab. Studio members were assigned fictional identities, fixed budgets, and an errand to accomplish by using various transit modes. Students realized how difficult—if not impossible—it can be for many Angelenos to carry on their daily lives with such unpredictable, expensive, or inconvenient transit options.

“This project offers an incredible potential social experiment,” said Josefina Aguilar, Executive Director of T.R.U.S.T. South LA. (Aguilar and her colleagues held an afternoon-long, community-exchange workshop with Sevtsuk and the studio at T.R.U.S.T. South LA’s offices in February.) With Dong and Lee’s plan, Aguilar was especially excited about the opportunity to solicit community input toward station-based amenities, imagining possibilities like street vendors operated by local residents.

A map of LA bus routes can resemble a pile of spaghetti more than a structured system. Bringing rail-system regularity to a bus schedule, while also opening highways to uses beyond cars and trucks, allows Dong and Lee to alter how passengers weigh buses in their transit decisions. By layering transit atop LA’s extensive system of highways, the designers aim to bring the transit to where people already live, or where their travel routes currently weave, instead of the more common method of trying to coax people toward where transit hubs are placed.

Similarly, Dong and Lee’s colleagues Andrew Yuzhou Peng and Solomon Green-Eames sought ways to revisit the densify-around-transit typology. Their proposal, “Change the Street, Transform the City,” brings bus rapid transit (or BRT) closer to community centers where density and amenities already exist, and seeks targeted, community-led street transformations, coupled with increased affordable housing, to create more walkable and bikeable neighborhoods.

Green-Eames and Peng consider LA a city of dense sprawl, one that is running out of the land that has sustained dreams of single-family homes on a hillside. They explain that LA’s urban form does not respond well to population density: With commercial land use that is based largely on strip malls, walking is inconvenient, and adding more people to the mix only compounds these difficulties. While Green-Eames and Peng see a current model of intense development around LA Metro hubs, they observe that those very transit centers aren’t necessarily where the actual cultural centers of neighborhoods may be.

“The existing model of transit-oriented development has failed to create truly walkable communities,” they write. “Our project proposes an alternative approach, through radical community-driven transformations, seeking to imagine how existing neighborhood commercial centers could become mixed-use, dense, and walkable centers, connected via a network of transit boulevards.”

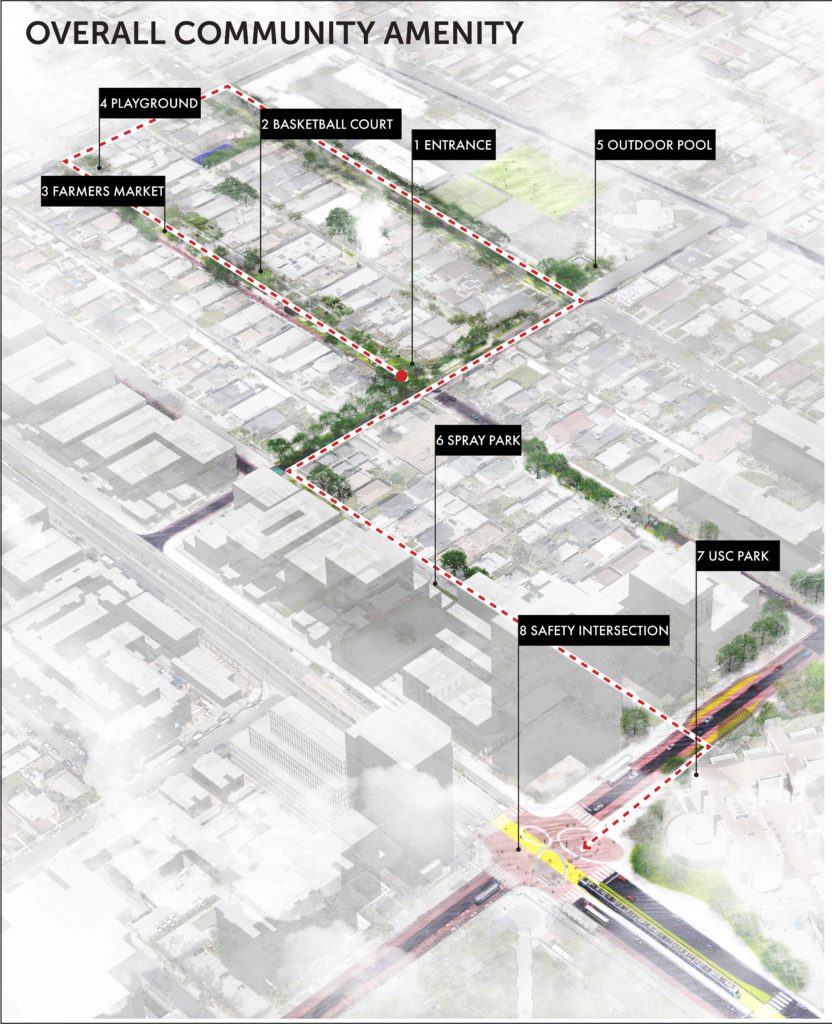

Zooming in on LA’s Jefferson Park and the nearby Crenshaw station on the LA Metro’s Expo Line, Green-Eames and Peng propose starting with low-cost, tactical, street-based recreational facilities by 2021, and making these temporary transformations permanent by 2027. Then, with a goal date of 2047, they propose inclusionary upzoning, adding new incentives to 2016’s Measure JJJ, which lays out affordable housing mandates and hiring restrictions around residential projects that require a zoning change or an amendment to the city’s General Plan.

More broadly, Green-Eames and Peng also propose a network of “transit boulevards” that include bike lanes, ride-share pick-up spots, and linear parks, all in one. The underlying concept is connecting transit hubs like Crenshaw to others, making it easier to hop from center to center via bus or bike.

Like Dong and Lee, Green-Eames and Peng seek to reimagine what “street” means: They envision the street as a more dynamic, urbane element, rather than just a conduit of cars and cars alone. They believe it can be a public platform that holds and enables a variety of uses, ideally maximizing both the efficiency and accessibility of travel and the quality of community life.

In adopting this view of “complete streets”—prioritizing pedestrians, bicyclists, and other users beyond single-passenger cars—these designers engage in an approach that has been taking root at the LA city-planning level. In 2016, LA’s Department of City Planning (LADCP) updated the city’s Mobility Plan 2035 with a stronger emphasis on the plan’s transportation section, which had last been touched in the late 1990s. Over the last two decades, new developments including bike-shares, ride-shares, scooters, and other mobility patterns have arisen alongside traditional transit systems, motivating city planners to apply a complete streets approach. What do pedestrian crossings and sidewalks need to include, for instance, in order to make people feel safe whether they’re inside a car or not?

“For the so-called ‘car capital’ to have policies that embrace complete streets, was a fundamental change,” said Claire Bowin, Senior City Planner at LADCP, during the studio’s February meeting in LA. “The city has been going through these growing pains—which is why this is a good moment for Andres and the studio to be here.”

Transit as Civic Instigator

In reinventing LA streets, Sevtsuk’s studio gestures toward a fundamental reconsideration of the city’s elements, where public and civic spaces emerge as the glue between those elements. With an eye to the value this can add, various Future of Streets proposals pursue transit as a way to provoke new investment, both financial and cultural, in LA’s public space.

“We could fit several Central Park–sized spreads in LA if we really wanted to,” observes the studio’s Bailun Zhang. Zhang and his partner, Lanchun Zeng, proposed “Less Parking, More City” as both the title and the mission of their LA reinvention. The design students investigated the LA Metro’s Expo Line—and specifically its Pico station—considering how many of the virtually countless parking spaces along the line could be reclaimed as public space, affordable housing, or other civic amenities. Zeng and Zhang started thinking beyond just parking spaces: Where does affordable housing exist today in LA, and where is it needed?

At the meeting with the LADCP in February, Sevtsuk’s studio learned that, as LA’s population continues to grow—currently at 4 million people, the population is projected to hit nearly 7 million by 2050—housing policy is of paramount concern. So Zeng and Zhang built housing into their formula, and also focused on LA’s “green-space deserts” and other critical needs, and how these needs might be addressed with pocket-park–sized parcels of land.

A common obstacle for both housing and transit development is displacement: Establishing a new transit station often makes the surrounding neighborhood more appealing, increasing demand and prices and forcing longtime residents to move out. The question of how to balance the interests of community members and real-estate developers is an essential component of the dialogue about urban development today. Students Dora Du and Sangyoon Lee analyzed current housing and zoning policy and proposed a clear mechanism through which to reinvest rising housing profits into the community. Their proposal, “Mutualism: A win-win model for communities and developers,” would subject new housing to new tax rates, and would accumulate the revenue into a fund to be collected and distributed through a community board.

Olympic Potential Looms

Amid LA’s continued expansion, one significant catalyst looms in the coming decade, promising economic growth but also possible displacement. With the 2028 Summer Olympics approaching, LA has the potential to inspire civic pride and engagement, but it also faces the complex questions of building and maintaining a massive amount of infrastructure—along with the parallel concern over what happens to all that infrastructure when the party’s over.

The city has some experience with this. The 1984 Summer Olympics instigated an extraordinary regional cooperation effort, in which Metro provided more than 500 buses to create a temporary transit network. Might the upcoming Olympics, and the infrastructural lift it inevitably demands, provide stronger—and sustained—momentum for transit-oriented growth?

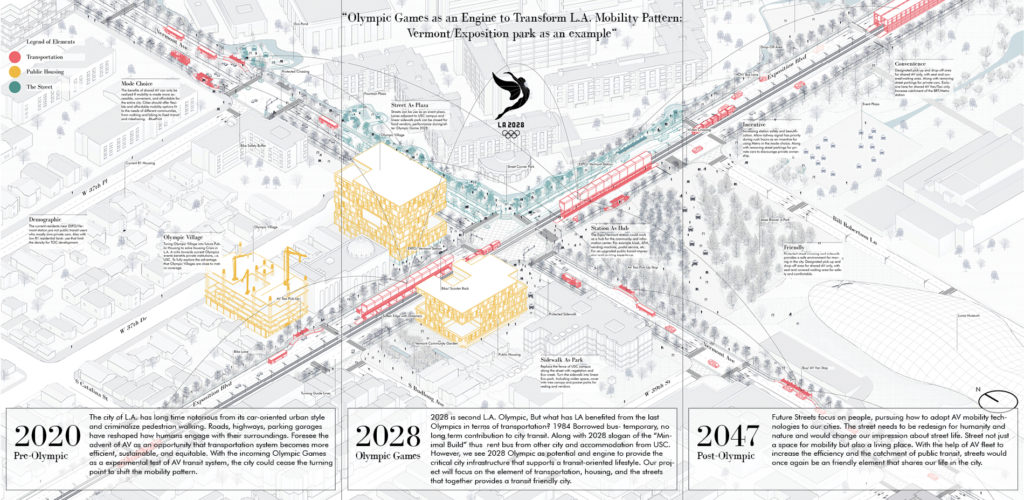

Amanda Ton, Ollie Xian, and Weihsian Chao think so. Their Future of Streets proposal, “Mobility as Equality: Building Towards the Olympic/Post-Olympic LA Transit,” leverages the Olympics as a means of coordinating transit planning and public housing development, eyeing the street design around the Expo Line’s Vermont station. The team argues that a mismatch between transit and its users has fueled low transit ridership: Many low-income transit riders have been displaced from transit hubs and forced outward, into the city’s margins and into cars, further marginalizing disadvantaged communities.

Anticipating 2028, they envision a next-generation bus system that can persist well after the last medals are awarded, while newly built Olympic housing is converted into public housing, managed by LA’s Housing Authority. They look to London’s 2012 Summer Olympics as a precedent: In London, so-called Olympic Villages were converted into affordable housing and integrated into transit rather than separated from it.

Transit that Connects, not Divides

As part of its goal of improving public transit, the Future of Streets studio was also interested in bettering the transit experience itself. Linyu Liu and Finn Vigeland looked at specific modal connections, transfers, and the time spent waiting for each—a tall order, given that two-thirds of LA Metro users make at least one transfer each trip. They saw transfer points that are neglected and difficult to use: Many lack signage, seating, or shelter, especially stations along the Expo Line, which runs down the center of major LA boulevards. A number of these stations are also very narrow and force transit users to cross wide streets and dodge traffic. They look and feel like afterthoughts because, in many cases, they are. Liu and Vigeland argue that such poor experiences, specifically with transferring between modes or lines, may explain why cross-modal transit use is so low in the LA Metro system. “A lot of small details can add up to a bad overall experience,” says Vigeland.

The history of LA’s development has generally clung to an east-west axis, and many boulevards and transit lines run in this direction today. But LA has become a more polycentric city, and north-south bus routes serve as vital circulators for huge numbers of Angelenos. Liu and Vigeland thus isolated north-south transit—which, incidentally, underlies many of Measure M’s proposals—as a principal need.

After weeks of mapping and data analysis, they targeted Vermont Avenue for its heavy bus use, as well as its interaction with the Expo Line. Their proposal, “Re-Designing the Multi-Modal Transfer System,” eases those transfer pain points: Flexible-use lanes would accommodate ride-shares and commercial loading areas; ramps would maintain an even grade between station platforms and sidewalks; and pedestrian and bicyclist crossing zones would be established. Their proposal reduces some of the seemingly minor, but collectively inhibitive, barriers to transferring lines or modes.

Investing in Transit for the Benefit of Everybody

For LA’s transit future, some of the most pressing questions are related to access: Who are “transit users,” and who might become transit users if it can improve, by becoming more efficient, accessible, comfortable, and reliable? The Future of Streets studio and their proposals aim to enhance the transit experience, while creating a new, more equitable, more accessible version of the LA that millions of people have chosen as home.

In all the dreams and visions of what transit can look like, in LA and beyond, LADCP’s Bowin distilled the equation succinctly. “We went out to voters and said, ‘When you pay more, this is what you’ll get in return.’”

In the wake of Measure M’s passing, LA Metro produced an advertising campaign that’s now mounted throughout the system’s stations. “There’s a movement in LA,” the text-only posters read. “It’s a movement fueled by people coming together to create the best life possible for our families and our communities. Our movement is leaving the smog and stress behind, saying Yes to dozens of new transportation projects that connect us to jobs, schools and opportunities to explore everything LA has to offer.”

“Yes, there’s a movement in LA,” the ad concludes. “We are the movement. And our time is now.”