Children may be celebrated for their non-rational thoughts, but society expects that adults will use reason. This belief is in part why dementia is often framed solely in terms of impairment, and why the dominant method of dementia care focuses on those reasoning faculties which are deteriorating or have already been lost.

According to Alicia Valencia (MDes ’19), however, an alternative approach is possible. Instead of concentrating so heavily on reasoning skills—by asking memory-impaired nursing home residents yes-or-no questions about the weather, or labeling everything in a way that insists on a set, singular identity for each item—why not focus on aesthetic engagement with the world? In her thesis, “Cultivating Aesthetic Play: A Case for Culture in Dementia Memory Care,” Valencia asserts that “the ability to perform aesthetic judgment still remains even as language skills and memory weaken.” She explains, “The capacity to decide whether something is lovely or not, to have certain feelings about the world, remains much longer in a person with dementia than knowing to put a book on a shelf.”

Valencia’s case study is personal: It’s based on her 81-year-old father, a resident at an in-patient memory-care facility in California. “The relationship I have with him might not fit the usual father/daughter label anymore, but it’s still an innate belief and knowledge that is beautiful to him in certain respects,” she describes. The way in which their relationship resists traditional classifications echoes her father’s connections with other elements of his environment, too. “The ways he and others at the facility make sense of where they are located and how they learn to call their new environment their own do not fall strictly into categories of reason, knowledge, short-term memory, or definitions of the world curated to a certain extent by the biomedical facility,” she says.

These observations resonate with an emerging area of dementia studies known as “critical dementia,” which reformulates the relationship between patient and practitioner by giving value to the patient’s potentially unorthodox behavior toward their surroundings. “It’s useful for a person who might be working well without the faculties of language, or when someone may or may not be emotional when they encounter something new,” Valencia explains. “It’s a way to broaden the scope of what can be understood as relatable to individuals with dementia.”

Critical dementia has its limits, though, she argues, as it still reinforces a framework of needing to render a patient’s activity intelligible to a practitioner. In other words, the practitioner’s way of making meaning in the world retains a level of superiority. Just as we foster positive interactions with children who have not yet internalized certain societal codes, Valencia proposes that we learn from individuals with dementia about different ways of functioning healthily in our respective environments.

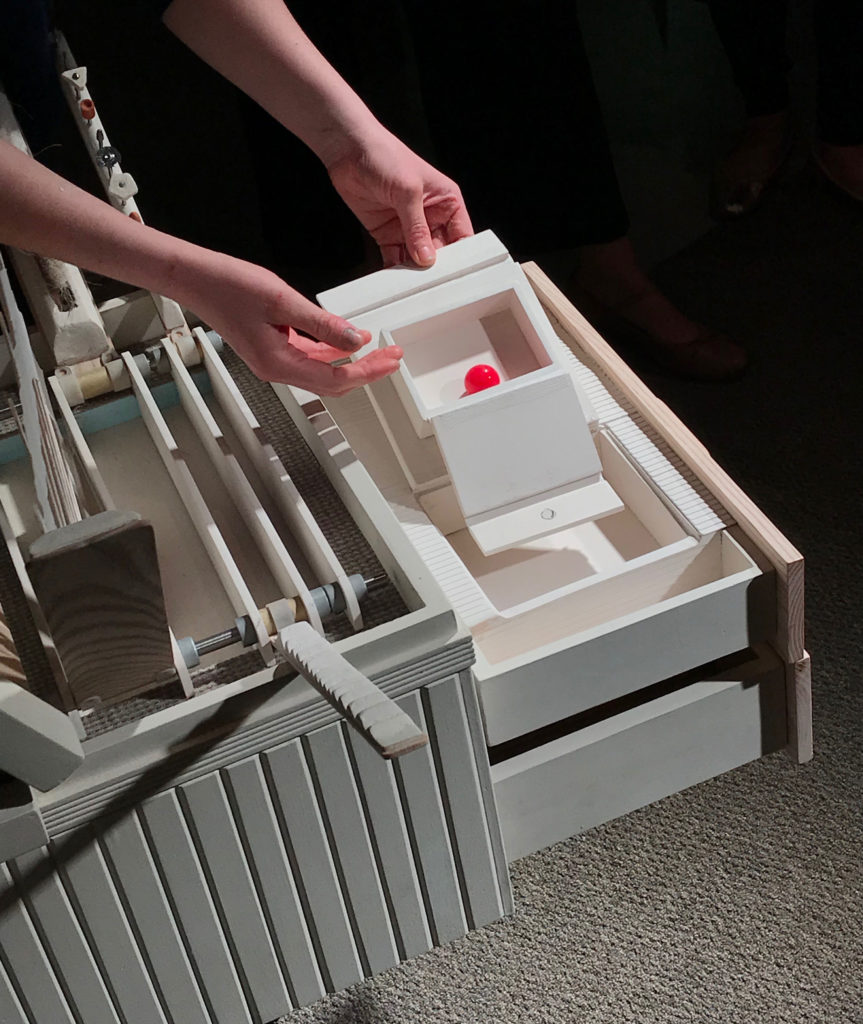

To explore this hypothesis, Valencia designed an object for her father based on his biography, his observed behavior in the facility, and also the ways in which he and other residents use both fixed and transitory objects in their shared environment. She explains, “He likes to zoom around in his wheelchair and pick out details in objects like crown molding or metal fixtures. He also has a history of breaking down his hospital bed just to see the different parts.” All of this resonates with his background both as an electrical engineer and as a professional cyclist. Inspired by his specific interests, Valencia created an object that resembles a Duchamp readymade. Designed to reflect his passion for tinkering and cycling, it has hardwoods different from those around him so that they might stand out, an assortment of sensory materials, drawers filled with various items, and a bicycle wheel affixed to the tabletop.

But it was also designed with his neighbors in mind and was placed in the hallway outside his room. “There is an open-door policy at his facility, so anyone can be roaming in and out of rooms. Everything is fair game so that it doesn’t stir aggressive behavior to tell someone they can’t be somewhere or have something,” Valencia explains. “As a catalyst for engagement to be played with, observed, and analyzed, the object has pieces that can be taken away and moved elsewhere within the broader environment. That’s based on people’s behavior of taking something from someone else’s room, walking around with it, and then later questioning why they have it in their hands and where to put it. This table is an example of how to design a hub of different malleable materials that could be adopted by each patient within the nursing home environment.”

Valencia hopes that the ways in which her father and others engage with the table will generate a body of evidence that challenges not only standard preconceptions about individuals with dementia and occupational-therapy objects but also caregivers’ and practitioners’ understanding of human environments more broadly. “A lot of enrichment activities are performed just to occupy one’s time,” she says. “But I hope the ways in which residents interact with this object can reveal relationships that would instigate the creation of additional design objects—perhaps made by the residents themselves. Because there are so few personal aspects to these environments, I wonder how something very direct and built from them could change the engagement and experiences within the nursing home.”