The strange and unexpected are disappearing from our towns and cities. In Europe and America especially, formulaic architecture has become a dominant mode, with unique structures demolished in favor of the more easily repeatable and unremarkable. Standardization also creeps into the countryside by way of expanding urban peripheries, where these designs are often found in abundance, and prompts concern regarding the disappearance of the natural. It is precisely these sterile environments that draw the attention of Robin Winogrond, design critic in Landscape Architecture and a founding partner of Studio Vulkan Landscape Architecture (Zurich/Munich). She had her students focus on such spaces in the Fall 2019 studio Geographical Reenchantment: Swiss Landscape Interventions between Atmosphere, Function + Experience in an effort to explore how landscape architects can transform banal, sterile, or even disappointing environments into those that stimulate the people who enter them.

“There’s a problem using the word landscape because no matter how hard we try, it still tends to conjure images of the pretty places ‘out there’—the field with the farmhouse, etc.—that are getting smaller and smaller all the time,” Winogrond says. “We’re talking about the contemporary landscape, or any space under the open sky. How can we look at those not-pretty places and find a powerful voice that’s worth being experienced?”

There’s a problem using the word landscape because no matter how hard we try, it still tends to conjure images of the pretty places ‘out there’—the field with the farmhouse, etc. We’re talking about the contemporary landscape. How can we look at those not-pretty places and find a powerful voice that’s worth being experienced?

On how landscape architects can transform banal, sterile, or even disappointing environments into those that stimulate the people who enter them

These contemporary landscapes are separated into three distinct but entwined layers: the natural, the cultural, and, much less frequently acknowledged, the imaginary. “At the cultural level, humankind starts to form things to cover up the layer of raw nature, to suffocate and manipulate it,” Winogrond explains. “Many groups—the ecology lobby, the recreation lobby, the farmers’ lobby, the highway and traffic engineering lobby—form the landscape as an operative resource for humans. But above these layers is the way we experience the landscape, which is based on fantasy, memory, longing, and other sensibilities like embodied experience. When you start to seriously consider that, you move into the perceptive realm and can talk about how we as landscape architects can use this to form our attitudes toward place in terms of stone, woods, vegetation, clouds, air, wind, fog, underground water, and smells and how they speak to an incredible need inside of us. And when you engage at the phenomenological level, you see how these three layers vibrate with each other.”

Coaxing the imagination in this way requires an attention to narrative. While architecture writ large is often presented and perceived through static images such as photographs, landscape architecture is predisposed to acknowledge the dynamism of our lived experiences as we move through and within a given space. This exists at a material level, too, where the decay inherent in vegetation leads to its regeneration. With this understanding, landscape architects can lead people through an experience. “You need that narrative to choreograph space, and you have to imagine it all as a coherent whole,” Winogrond says. What is critical, however, is that a space’s possibilities are never limited. “You never say what everyone has to experience,” she adds.

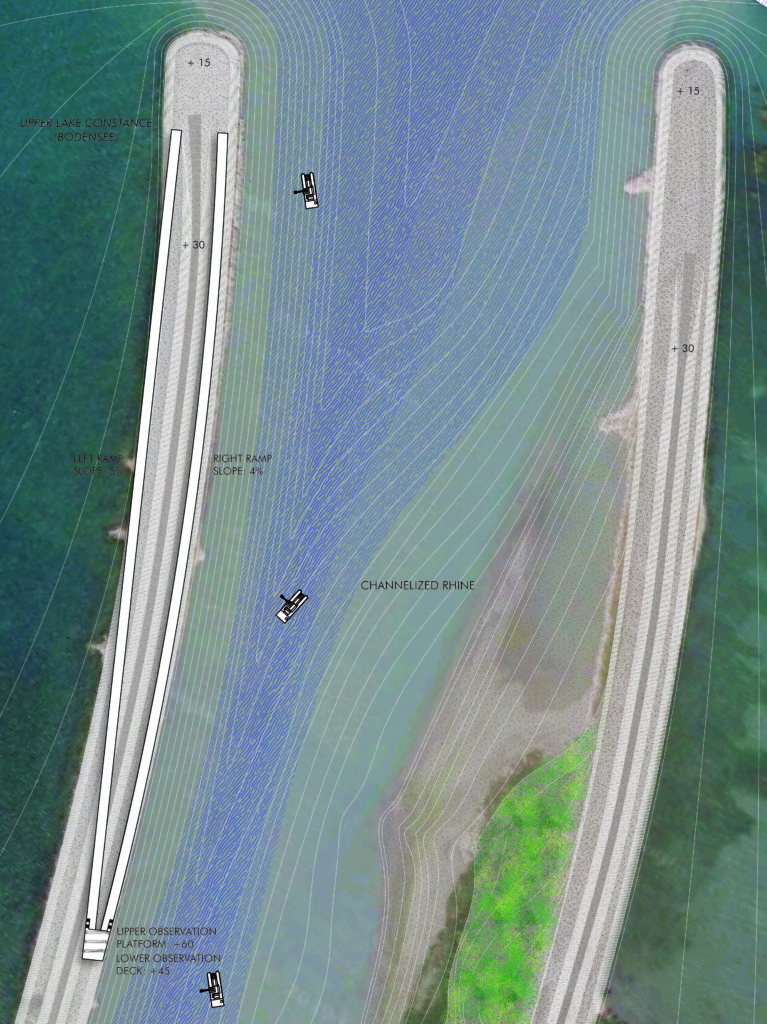

Kira Clingen’s (MDes ’21) “End of the Rhine” is a 1,250-foot-long ramp leading to two observation decks. “By choreographing a path through the strange structures that the dams and dredging produce, the platforms provide a juxtaposition between the natural and the culturally engineered.”

In the studio, Kira Clingen (MLA/MDes ’21) addressed one aspect of decay and the mass movement of natural material with a project located where the Rhine River enters Lake Constance near the Switzerland-Austria border. Multiple dams in the area shift the path of the Rhine itself and also transport silt to prevent the stoppage of the river’s flow. “It’s a huge machine going through the landscape,” Winogrond says. “They built the dams two miles into the middle of the lake, which creates a curving, double-dam image. The water is in the dam and outside of it. Every day, a machine dredges the silt and makes shapes with it alongside the dam—biotope habitats, among others.”

Clingen designed a 1,250-foot-long ramp along which people walk toward two observation decks: one with an unobstructed view of the Alps, the other looking out to the “constant evolution of dredged sediment, spontaneous vegetation and rushing water through the Rhine channel at the Rhine-Constance confluence.” By choreographing a path through the strange structures that the dams and dredging produce, the platforms provide a juxtaposition between the natural and the culturally engineered. They invite an appreciation of the latter’s beauty both in contrast to and in concert with the surrounding mountains.

Lu Dai’s (MLA ‘20) “Dance in the Fog” highlights the presence of the fog at the popular tourist destination at the summit of Hoher Kasten in Switzerland.

While Clingen worked on a landscape rarely considered for its splendor, Lu Dai (MLA ‘20) reconceptualized a site renowned for creating feelings of awe. The summit of Hoher Kasten, a mountain in eastern Switzerland, has become co-opted by the tourism industry for its spectacular views: Visitors come for the walking trails and to eat at the aptly named Panoramic Restaurant. Yet despite efforts by humans to control this area and maximize experiences dependent on clear visibility, the weather—especially the fog—remains unpredictable. Instead of accentuating the normative interests of the tourism lobby, Lu recognized that fog is the dominant voice in the area and that it could be the subject of an intervention that highlights it as “mysterious, unexpected, fleeting, constant, horrific, thrilling, and beautiful.”

In tune with the area’s topography, she directs the fog—and the people moving within it—using a series of walls, stairs, and platforms, some of which have holes through which the fog moves and others that accentuate the sound of the wind. In total, the structures inspired by the fog’s unalterable presence introduce novel means by which, she argues, the visitors feel attuned to “danger,” “nature,” “the unexpected,” and themselves. The existing infrastructure at the summit and the fog that was until then considered largely in negative terms become the starting point for, in Winogrond’s assessment, “a magical experience.”

In each of these projects and others produced by Winogrond’s Studio Vulkan, the goal is not destruction in an effort to create more beautiful, tranquil, or sustainable alternative structures, nor is it to become confrontational with various lobbies that use the land as an economic resource. Rather, the interventions begin by accepting the existing contemporary landscape as a lived reality and then transforming it in ways which shift our engagement from passive to active.

“I feel courageous about going into these strange places and having the patience to say, ‘What’s going on here? What are we actually talking about and what can we express?’” Winogrond says. “It’s not a plea for the laissez-faire. Our cities becoming generic is a dramatic problem. But that’s not in our hands as landscape architects. What is in our hands is a willingness to wrangle with these landscapes. It’s a great moment of freedom, and I think the students were happy with their projects because they all found keys to doors that turn these difficult situations into something you really would want to experience. It’s a moment of hope and almost joy to have an approach that there is no bad place.”