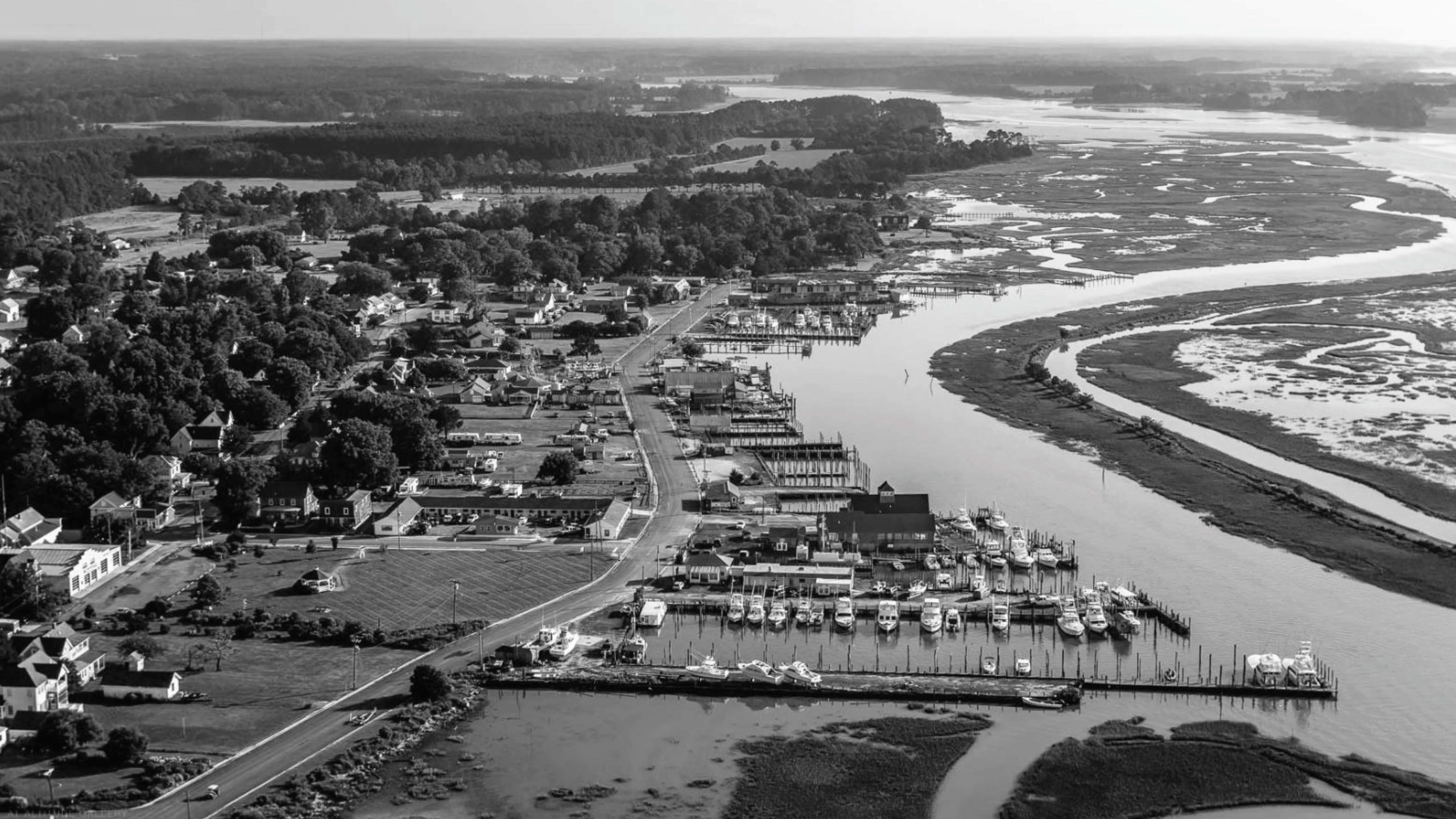

A lone farmstead is perched on the edge of a creek on Virginia’s Eastern Shore. Dozens of acres of cornfields unfurl behind the structure, eventually blending into a swampy marshland lined with salt hay. On first glance, the house and its manicured lawn are a postcard of idyllic coastal living. But they also inhabit a deeper role, as a barrier between the residents’ increasingly precarious livelihood and the area’s continued coastal erosion. Each year, exaggerated salinity in the soil creeps a foot further inland, threatening the survival of the Eastern Shore’s farming industries even before the land is actually claimed by the sea.

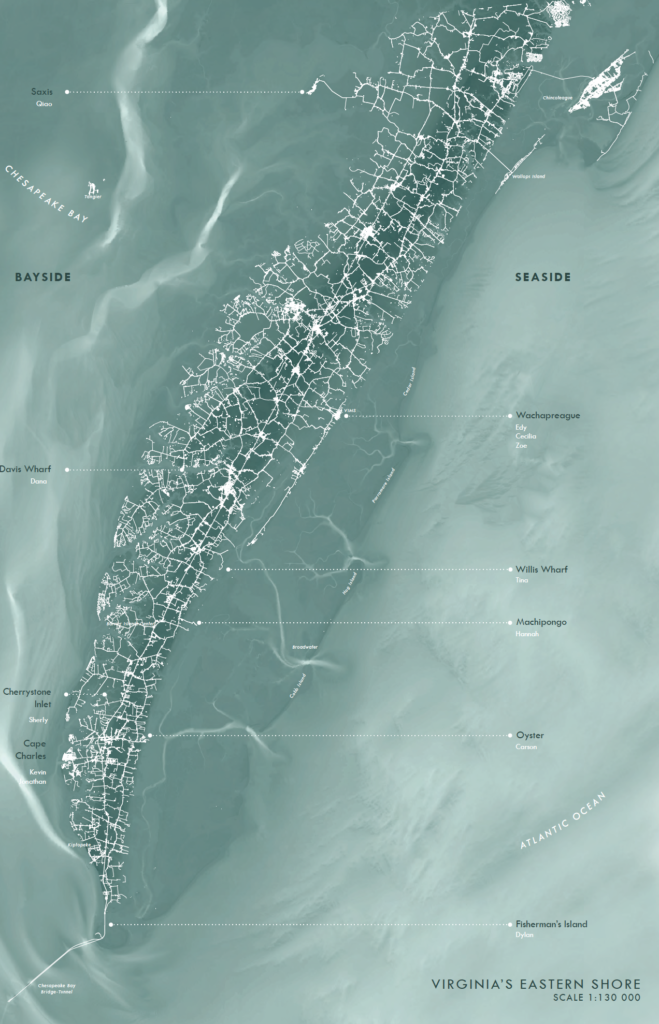

In the next 40 years, two-thirds of the land mass of Saxis Island, where this farm is located, will disappear into the adjacent Chesapeake Bay. With just three to four feet of additional sea level rise, Saxis will be swallowed by water on all sides, rendering its approximately 230 inhabitants isolated and stripped of their farming resources. Yet many residents of Saxis and other high-risk towns dotted along the 70-mile peninsula refuse to budge.

Is continued human settlement of a coastal area poised for such extreme and potentially devastating change truly worth fighting for? What sort of circumstances—both practical and ideological—anchor the drive to remain? And how can new land-use strategies enable the continued occupation of a region whose residents largely don’t believe in climate change? It’s a challenging, fascinating premise with no easy answer. Gary Hilderbrand, the Peter Louis Hornbeck Professor in Practice at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, devoted his option studio last term to uncovering the stakes of these questions—for Virginia and beyond.

“This was unlike any studio I’ve done in my 30 years of teaching at Harvard,” says Hilderbrand. “It was much more expansive and experimental—the students chose the sites and topics for their research, which resulted in a wide-ranging atlas of ideas.” As per usual in Hilderbrand’s studios, the dozen fourth-year students in Adrift and Indeterminate: Designing for Perpetual Migration on Virginia’s Eastern Shore hit the ground running. A four-day visit to the Eastern Shore in the third week of the semester enabled them to get close to their sources and stake out the nature of their projects. A shared camp site nurtured communal discussion, while the support of a sponsor family drew the students intimately into the lives and stories of the local farmers, fishermen, scientists, and employees of the Barrier Islands Center who call the peninsula home.

An induction to proper fieldwork methodology from the GSD’s Gareth Doherty—who teaches at the intersection of landscape architecture and anthropology—helped prime students for the task at hand. Background knowledge on climate change in coastal cities, gleaned from a full year of core studios the year before, coupled with the regional expertise of local coastal geologist Chris Hine, nudged the students’ projects into a unique terrain. The students designed interventions—both specific and speculative—for sustaining human habitation of precise areas along the Eastern Shore, while also responding to the broader issue of future coastal life in the throes of climate change.

“As the studio kicked off, the topic of migration was and continues to be very timely in US politics,” Hilderbrand explains. “Farmers and watermen have been migrating away from the edge of land here for generations. It also scales up and presents a picture of coastal climate change as a long-term phenomenon that has witnessed centuries of human movement.”

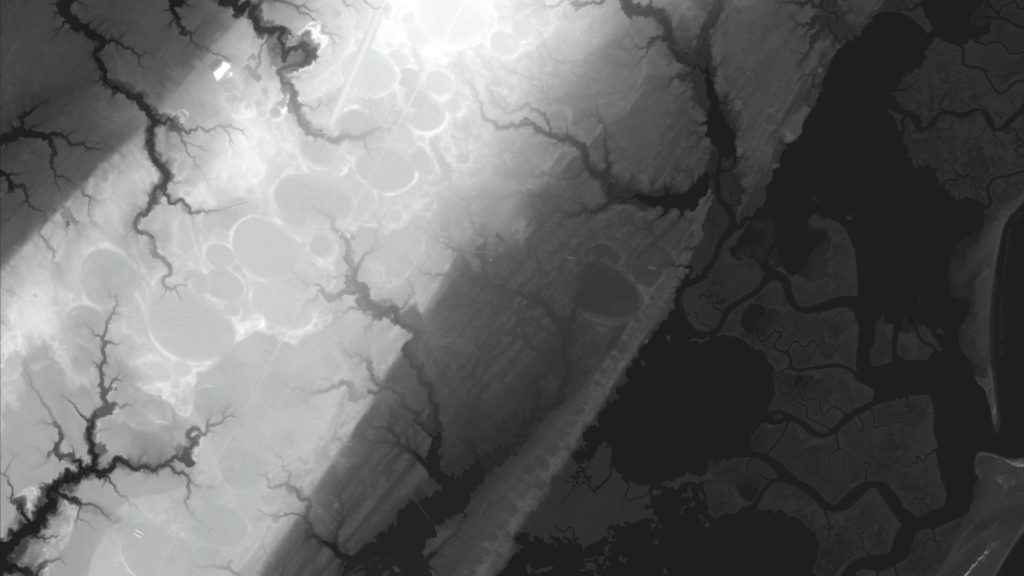

The studio’s outcomes—both an “atlas” of investigation and a collection of design projects that look both forward and back in time to propose ideas for the future survival of the area—is a layered and dense body of work that belies the short time frame of the course. The atlas work is loosely divided into 10 categories: Settlement, Ecosystem, Atmosphere, Place, Economy, Property, Building, Sand, Protection, and Displacement. The subsequent design projects interlock through their shared ambition to unearth a dense network of political, cultural, technological, and religious histories of the area that frame the residents’ position on climate change and the future survival of the region.

Beginning with the region’s self-determined infrastructures built in the 19th and 20th centuries (such as stick-built barns raised by entire communities), to the first signs of federal intervention (including light houses and post offices), and finally, to the introduction of transportation infrastructure (including the railroad in the 1880s and later, highways), we witness a land of self-selected and resourceful residents who have carved out a life in a region many of us would write off as remote and inhospitable. Tracing the cultural influence of American Methodism (which was founded here) and contemporary conservative politics (more than 50 percent of voters in the region supported Trump in the 2016 presidential election, with some local districts reporting far higher), the atlas gracefully traverses the social conditions underlying the area’s general resistance to notions of climate change. But it burrows deeper than party lines, examining the narrative of constant displacement that has framed life here on the Eastern Shore for as long as anybody can remember.

From erecting 12-foot-high platforms to elevate their homes, to annual “sand nourishment” initiatives aimed at stabilizing the coastline, residents undertake elaborate measures to sustain life in a place that, on an almost daily basis, recasts its boundaries between wet and dry. The economy section of the atlas examines the transition of a place that was once considered a breadbasket of America into an area that now mostly produces poultry and soy products in addition to the ubiquitous blue crab. Those industries persist despite the fast erosion of the shoreline, the breaking apart of the 23 barrier islands strung across the peninsula’s east coast, and the unstoppable salination of what’s left of farmable land.

The atlas also investigates the complex understanding of the landscape among residents. People have been moving upward and away from the barrier islands for the last 200 years; climate change has always been happening here, albeit a lot more slowly than it is now. For these locals, the perpetual shape-shifting of the landscape has been a part of life; as such, they are hesitant to view the increased severity of change in recent years as anything out of the ordinary. With this context in mind, the studio worked to design possible means of managing the impact of climate change that are, in Hilderbrand’s words, both real and speculative.

“There are essentially two stances on sea level rise right now,” explains Hilderbrand. “One says that resiliency is not an option and that we have to retreat, while the other suggests that there are reasonable ways of protecting these assets—indeed, peoples’ lives and livelihoods—for some admittedly questionable period of time.” Hilderbrand’s studio wanted to posit a third way by seeing those beliefs as two end poles of a spectrum. How might fresh land-use strategies mitigate the impact of climate change on the coast by encouraging alternative ways of inhabiting it? Is it possible to carve out a new understanding of the intensifying forces of erosion and salination that does not inherently clash with the residents’ perception of these processes?

The students offer up a variety of innovative ideas, some of which read as clear architectural interventions while others are more ideologically oriented and suggest revamped notions of civic space and understandings of heritage. A particularly fascinating project ditches the coast for a through line that unfurls across the peninsula. Selecting a site bookended by the Barrier Islands Center on the ridge of the peninsula and the Box Tree Farm (owned by the Nature Conservancy) on the shore to the east, the student suggests this space as a new kind of public commons, on what was formerly private property. With a focus on building up the inland area while the coastline is changing, this forward-looking proposal—along with several others—encourages residents to remain aware what it means to work as a collective with respect to land tenure and to continually build on higher ground.

While students were predominantly drawn to the studio because of its rural subject (“I am committed to turning our students into urbanists, but this studio became irresistible to me,” remarks Hilderbrand), two of the ten projects focus on Cape Charles, a historic city built by a 19th century developer at the termination of the Eastern Shore Railroad. The majority of Cape Charles is predicted to be underwater in 60 years. One student suggests sacrificing two blocks of the city spilling out onto the beach that were not part of the original design, in order to buy time for a 30-year migration of the historical houses. Another suggests rebuilding the city entirely and densifying it on higher ground.

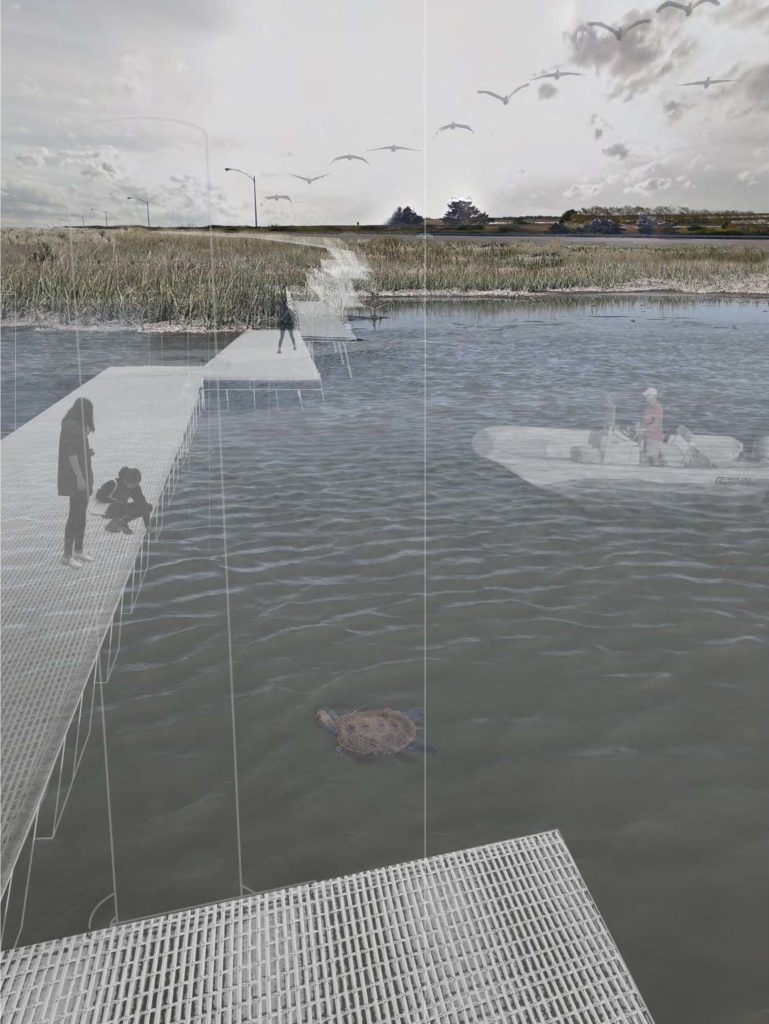

There are also projects that propose working with the eventual flooding of the land rather than against it. Fisherman Island, which grew from a 19th-century shipwreck at the southernmost reach of the barrier islands, is the only landmass on the Eastern Shore that’s increasing in size. One student proposes an elevated walkway that transforms the disturbed land of the highway side-slopes into a visitor experience through a new observatory that would also enable a protected species of turtles to pursue their natural migration patterns. Arriving by boat would allow more explorers to visit than the current six-person daily quota, and it would potentially provide more jobs in an area with a higher-than-average unemployment rate.

Another project reimagines Willis Wharf in Little Hog Island, on the seaside, some 80 years in the future: thick forests of mangroves suppress wave action, with additional help from a dyke, elevated buildings, and residents who have transitioned from land-based agriculture to aquaculture.

“I try to root my teaching in real problems, direct evidence, and real places, with real experts helping us frame the work and measurable data backing up our suppositions,” says Hilderbrand, who maintains a similar approach at his landscape architecture practice, Reed Hilderbrand. “But it must be speculative, too. We have to imagine a future that we cannot quite predict. This is especially true with regard to the dire predictions we face on the climate front.”

Hilderbrand’s studio offers up solutions for remaining connected to the landscape in both work and life, and proposes design interventions that take on board the dominant ideologies of those inhabiting this increasingly precarious peninsula. The atlas can be understood as something of a roadmap for a more mindful and experimental approach to landscape architecture. In the face of an unpredictable future, more generous speculation, and the entanglement of opportunities it conjures, might just be exactly what we—as well as the residents of Virginia’s Eastern Shore—so desperately need.