The global COVID-19 pandemic has placed roughly one-third of the human population on some form of lockdown. But with spring in full swing, economies in free fall, and infections on the decline in early hotspots, many are antsy to get back to work, school, and life as we once knew it. Health experts, citing disease models, warn that easing restrictions too soon could cause the virus to flare up again. The silver bullet of a coronavirus vaccine is still at least a year out, which means the burden of containing the epidemic continues to fall on the public, who must sustain distancing behaviors even as it costs us our jobs, social lives, and everyday routines. But when the worst appears to be behind us and we’re finally descending the other side of the curve, how will we convince billions of people, blinded by the light at the end of the tunnel, to keep cooperating until COVID-19 is gone for good?

Harvard Graduate School of Design alum Michael de St. Aubin thinks better-designed disease models can have a greater impact on the public, as well as on healthcare and policy decision-makers, by helping us to see just how much our actions matter during the midst of an epidemic and after we’ve flattened the curve. Combining the sophisticated mathematical formulas of an epidemiological model with the look and feel of a computer game, his Visual Response Simulator, or ViRS, is a web-based visualization tool that’s designed with non-experts in mind. “The [visualization of inputs and outputs of] models used by health professionals or referenced by media outlets come from academic institutions—they’re set up for people with a background in epidemiology, and they’re kind of archaic,” notes de St. Aubin, an architect by training. “ViRS brings these ideas up to speed with modern interaction and visualization. It makes disease modeling more accessible to a wider audience by making it as easy as possible to understand.”

De St. Aubin plans to partner with video game designers to create ViRS’s interactive interface. The platform is specifically designed so people can test the impact of different outbreak response strategies (such as vaccination, public education, or mobile health facilities) from the moment they are implemented, and quickly see what happens when these interventions are scaled up or down. Traditional disease models, by contrast, demand any response tactics be determined at the outset, and require dozens of epidemic simulations run to their completion before returning the mean results. “I’ve built ViRS so the user can control and change their strategy mid-simulation run,” de St. Aubin points out. “It gives you the interaction to manipulate it in real time and visualizes all of those effects so it’s easy to see what’s working.”

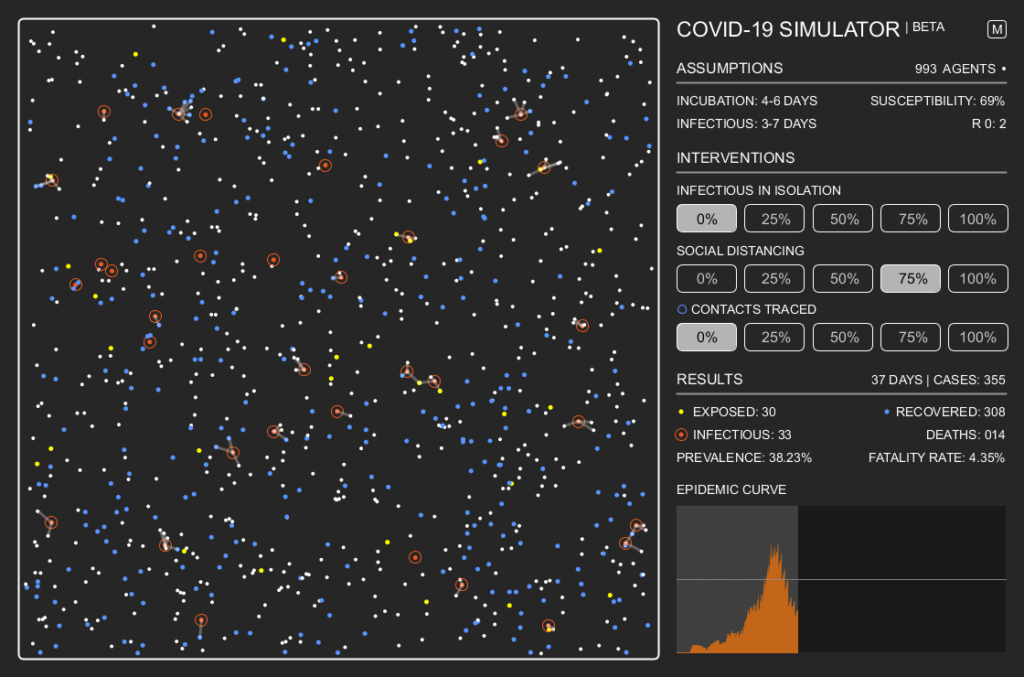

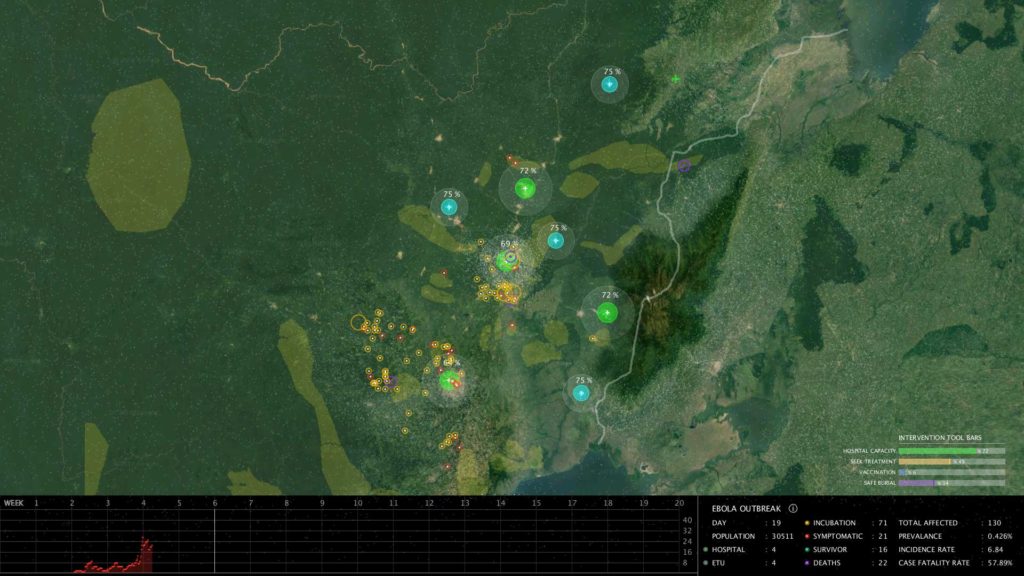

Also unique is the integration of satellite imagery and geo-spatial data, which factors in population density, transportation networks, and existing hospital facilities in a given location. ViRS’s on-screen simulation provides a bird’s-eye view as a population of autonomous agents is ravaged by disease in accelerated time. Toolbars allow for toggling intervention variables, while counters track the total number of exposures, infections, and deaths. As the disease progresses, a now-familiar epidemic curve plots out the levels of infection over time, with spikes and dips appearing where interventions were imposed or lifted.

De St. Aubin began developing ViRS in 2017 as a graduate student in the Risk and Resilience concentration in the Masters in Design Studies program. Originally designed to model data from Ebola outbreaks in Western Africa, the simulator can be tailored to the characteristics of any disease, real or hypothetical. While in quarantine over the past several weeks, de St. Aubin adapted ViRS to create a basic interactive simulation for the current COVID-19 pandemic, using scientific research on the disease’s dynamics. “Right now, a lot of people are interested in epidemiology models and how they’re used. This particular model is for public engagement and knowledge sharing,” he says. The COVID-19 simulation lets users see for themselves how adhering to social distancing and self-isolation guidelines can dramatically flatten the curve of the outbreak, and more critically, what might happen if such restrictions are lifted in the crucial months ahead.

In this simulation, the hapless agents are rendered as dots moving around inside an empty box, bumping into and infecting one another with increasing speed as the disease permeates the population. But with one click, users can enact social distancing measures that immobilize 25 percent, 50 percent, 75 percent, or 100 percent of the dots and send the infection curve plummeting. Remove the intervention tactics and infection rates resume their climb once more. “It’s a simple tool people can interact with and learn from, and it demonstrates why these non-clinical public health interventions are so important,” says de St. Aubin.

Since graduating in 2018, de St. Aubin has been working with the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative and continuing to refine ViRS to model response strategies for combating Ebola. (With another team at the H.H.I., he has also developed a global COVID-19 perceptions, knowledge, and behaviors survey, and a dashboard for visualizing and filtering survey data.) While ViRS is not yet validated for official use, de St. Aubin already foresees how the platform could bring value to a number of different applications.

Primarily, he envisions ViRS as a tool to get the public to learn about, support, and adhere to health guidelines. “The interaction and the visual qualities make it much easier to convince people how—if these intervention strategies are followed and to what degree—the outbreak can be contained and come to a stop,” he says. Its multiple-scenario, game-like properties, and graphic interface also make ViRS an ideal tool for epidemiology and outbreak training and education. Further, when used operationally in the field, the simulator could rapidly test response tactics and inform contingency plans, while making data easy to visualize and share for coordinating response efforts across teams.

De St. Aubin first became interested in public health and epidemiology in 2015, while working as an architect in Boston. Traveling to Ebola-stricken regions of Africa to do hospital facility assessments, he saw outbreak response in action. “There was a huge lack of designers in this profession and not a lot of design thinking, or design sensibilities,” he recalls. “I felt like I could fill a gap. I went to school thinking, ‘How can I increase my value as a designer and integrate myself into this field full-time?’”

At the GSD, de St. Aubin found the Risk and Resilience concentration a natural fit with its commitment to countering social and political issues through design. There, he took a step away from architecture, pursuing research in mapping, technology, and humanitarian response, augmented with classwork at the Harvard School of Public Health and a data visualization course at MIT. Although he was the only student in his cohort focused on infectious disease modeling, de St. Aubin predicts the growing threat of global pandemics will inspire more designers to become interested in this area. “If designers are really serious about making a difference, we can’t continue to operate in a vacuum,” he says. “We need to integrate ourselves with the fields and organizations that are doing the work directly and leading the charge, working with different UN agencies, different international organizations, and local NGOs as well.”

COVID-19 has spurred architects and designers around the world into action; they’re creating open-source files for 3-D printing respirator valves and face shields, translating the UN’s critical health messages into impactful graphics, and designing temporary coronavirus testing facilities. This unprecedented global pandemic has taught us that design can play a crucial role in better preparing us for the challenges and opportunities presented by future outbreaks, and that our individual actions and contributions can make a huge difference for the welfare of the greater good.

“Designers can get involved in so many ways, not just disease modeling, but also planning—coming up with policies and guidelines for our urban spaces to be more adaptive to these sorts of things. Rethinking how people are going to be living in the future so it’s not a total shock to our communities and our economy when everyone is forced to stay at home,” says de St. Aubin. “Our creativity and ability to forward-think is going to be really useful. There’s going to be so much need and focus on that for better resiliency in the future.”