Princess Faniyi in front of Gund Hall, Harvard Graduate School of Design. Photo: Moisés Lino e Silva

Princess Adedoyin Talabi Faniyi traveled from Osogbo, Nigeria, to address the 2019 “Sacred Groves & Secret Parks” colloquium at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. The high priestess ceremoniously clanged a handbell as she called out to the audience: “To Osun, the Orisha of the waters of life, we pay homage. We say ‘asé.’” Those in the room—practitioners, scholars, and students alike—joined in chanting “asé,” which served as both the call and the response. “Let she clear the path of this conference. Let she clear the path of everyone. And may we have the successful outcome…and let the knowledge and wisdom that we share be useful for everyone.”

The two-day colloquium focused on the landscapes of Orisha, a pantheon of spiritual figures originally worshipped by the Yoruba people of what is now Nigeria. Despite taking place at the GSD, the first presenter was Professor Jacob Olupona of Harvard Divinity School. Olupona—while pushing back against the notion that the spectrum of African spirituality can be categorized monolithically—introduced the audience to common ties that religions of the continent do share: to the spatial and material environment, to the Earth’s processes, and to human culture and community.

Faith in Orisha has endured in Yorubaland despite the violence of colonization. It also crossed the ocean to the Americas during the four centuries of the Atlantic slave trade, when as many as 15 million West Africans were kidnapped and forced into labor in the colonies of the New World. Santería, for example, traces its roots through the enslaved people of Cuba, and Candomblé is the most pervasive Orisha-based religion in Brazil.

Following Olupona’s overview, the chief organizer of the colloquium, Associate Professor Gareth Doherty, explained that speakers from Nigeria, Brazil, France, and the US would compare and contrast those “landscape traditions that fall outside of the normal Western practices.” Scales of both design and disturbance would range from the global to that of site and details.

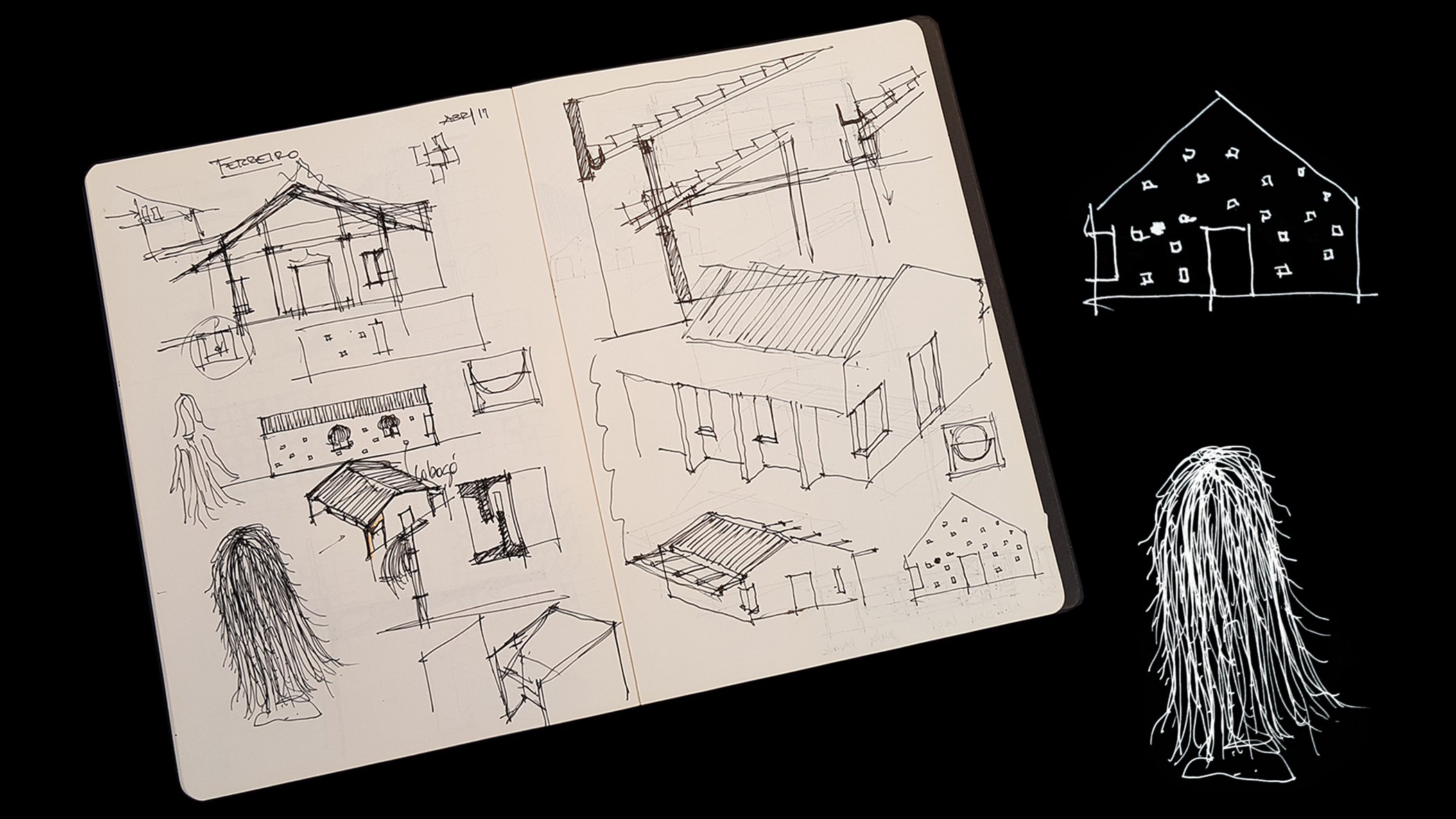

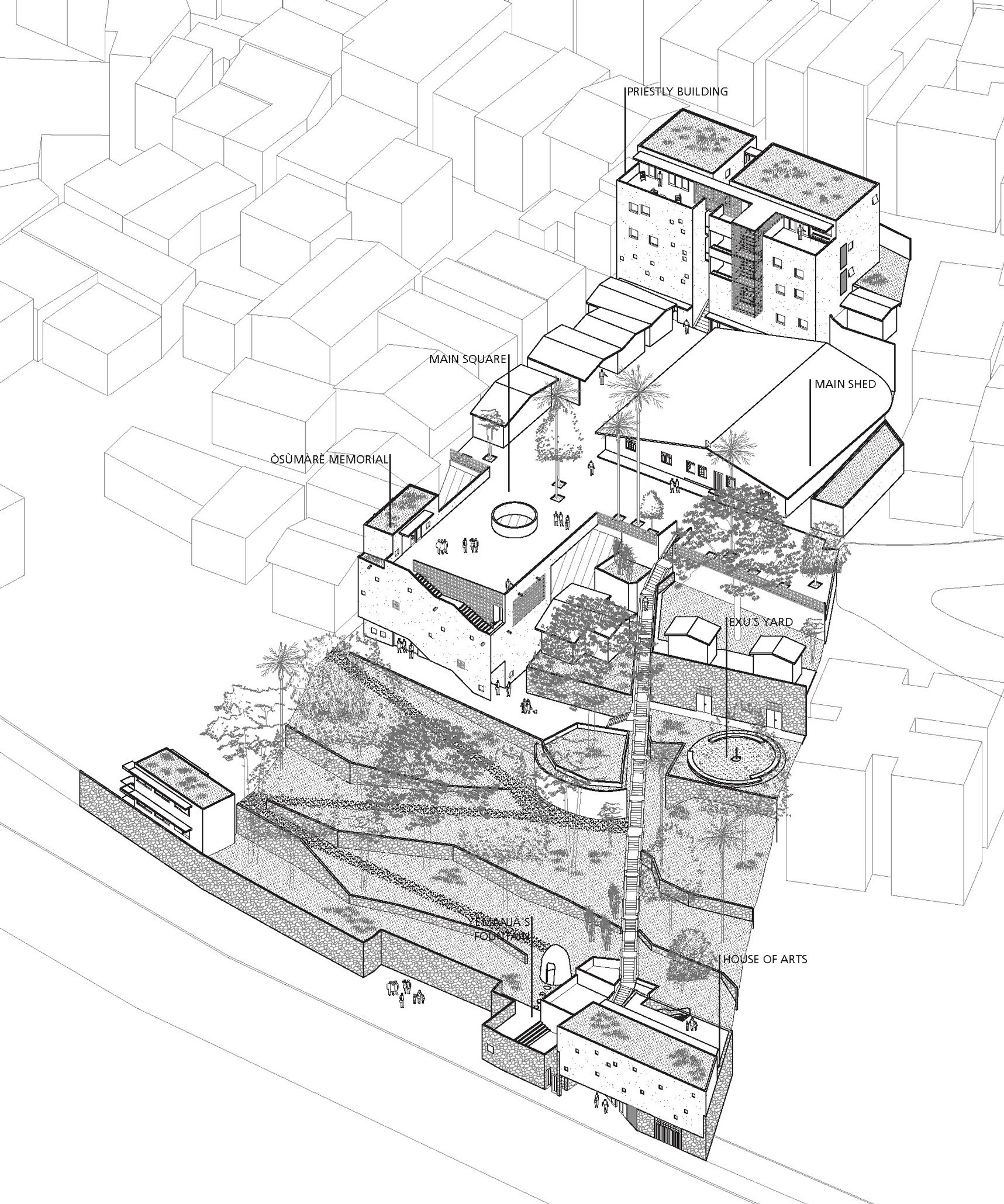

Form and ritual documented though architect’s sketches at Terreiro Tingongo Muendê. Credit: Sotero Arquitetos / Adriano Mascarenhas

From Doherty’s own fieldwork in Yoruba and Candomblé landscapes, he presented on the intriguing dimensions of an entrance stairway—with 134.5 risers—at Casa de Oxumarê, a terreiro [shrine] in Salvador, Brazil. When Doherty had questioned the worshippers about the curious half step, they acknowledged that the dimensionality had significance but didn’t give a reason. During a field visit in Nigeria, Doherty noticed a similar stairway condition; the explanation that was offered related to a generosity engrained in Yoruba culture.

Demonstrating those strong transatlantic bonds among Yoruba-rooted religious spaces, Moisés Lino e Silva, assistant professor of anthropological theory at Federal University of Bahia, introduced the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove in Osogbo, Nigeria. Reflecting on his own experiences with Candomblé in Brazil, Silva revealed the “combination of art, religion, and ecological concern” that came to guide the creation of this rich sculptural place. Not only is the Osun Grove a landscape of beautiful sacred forms and cultural space for the Yoruba people, but with its recent listing as a UNESCO Heritage Site, it has helped secure the legal protection of ecosystem benefits. The Grove is one of the largest swaths of urban forest remaining in Nigeria.

Vilma Patricia Santana Silva, an architect training in Salvador, discussed her work volunteering with terreiro community projects. In designing and assisting in the construction of her works, Silva communicates directly with the Ilê Àse deities for guidance. Her discussion of a spiritual conflict between one specific tree and a terreiro structure prompted Gary Hilderbrand, GSD professor in landscape architecture and principal at Reed Hilderbrand, to pose a question to Silva and the panel regarding the “larger responsibility” of designers on urban sites, especially in development-intense Salvador, where Candomblé terreiros are some of the last patches of green.

Another speaker, Vilson Caetano de Sousa, Jr., a priest and a professor at the Federal University of Bahia, gave the audience an in-depth analysis of plants. Discussing the continental origins of multiple plant species, Sousa demonstrated strong ties between Latin American and African culture and spirituality. Like the Yoruba faith, plants were carried with the enslaved people from Africa to the Americas.

Condomblé, Yoruba, and other Afro-diasporic, syncretic religions are united by more than just their respect for Orishas. Their practices and rituals are inherently land-based, often taking place outdoors, and, due to urban development pressures, are increasingly being forced into public-realm landscapes. Religions of the African continent also experience violent persecution. As Olupona described in his overview, “there are millions who fear it…millions across the world” who exert “time and energy trying to destroy it.” In fact, until 1977, the public practice of Condomblé was illegal in Brazil.

Like all human activities, worship shapes both the space and the materiality of the land. But the sacred landscapes of Orisha and the religious practices that take place within them are vulnerable: even as legal and social tolerance may be slowly improving, urban development and scarcity are an ever-increasing threat. The colloquium fostered productive and revelatory conversations about the complexities and richness of spiritual culture and its relationship to the landscape. But, as Doherty said at the beginning, the program was about more than just educating and informing; it was also about subverting and “decentering Western canons of knowledge.”

The Sacred Groves & Secret Parks colloquium and exhibition was hosted by the Department of Landscape Architecture in collaboration with the Afro-Latin American Research Institute, Brazil Studies Program, David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Center for African Studies, Center for the Study of World Religions, Frances Loeb Design Library, Provost’s Fund for Interfaculty Collaboration, and Weatherhead Center for International Affairs.