Pairs is a student-led journal at the Harvard Graduate School of Design dedicated to conversations about design that are down to earth and unguarded. Each issue is conceptualized by an editorial team that proposes guests and objects to be in dialogue with one another. The following is an excerpt of a conversation from Issue 01 between Pairs co-founder Kimberley Huggins (MLA I ’20) and Sara Zewde, Assistant Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, titled “On the Foundational Spirit: W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits.”

Pairs is a student-led journal at the Harvard Graduate School of Design dedicated to conversations about design that are down to earth and unguarded. Each issue is conceptualized by an editorial team that proposes guests and objects to be in dialogue with one another. The following is an excerpt of a conversation from Issue 01 between Pairs co-founder Kimberley Huggins (MLA I ’20) and Sara Zewde, Assistant Professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, titled “On the Foundational Spirit: W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits.”

KIMBERLEY HUGGINS So, “Cotton Kingdom, Now”: your return to and inaugural class at the GSD!

Your class is occurring during a time when the dominant narratives of history and their intended values are being seriously questioned. In the context of the education of landscape architecture, this sentiment often materializes in the student body as a desire to toss the canonical history and start anew. Students struggle to see how it is equipping them in the face of contemporary social and environmental realities. Subsequently, there is a desire to excise it. It is not uncommon to hear students say, “I do not want to hear about Olmsted anymore. I do not want to talk about gardens anymore.”

And so while many are asking for the focus to be moved from Frederick Law Olmsted with a belief that the more relevant lessons are elsewhere, what was it that drew you in further to focus on his time as a young journalist?

SARA ZEWDE The landscape architecture that is taught at the GSD now is significantly different than the landscape architecture I learned when I started in 2011. Even a comparison after a few years is mind-boggling. Things are rapidly changing and it is not like that change started in 2011. When I speak with students who studied before me, it becomes clear that there have been a number of significant shifts within the last 15 years in landscape architecture education.

I don’t think there was a single Black person referenced in my three years of landscape architecture education. Be it in a syllabus, a chance to read their writing, to learn about their thoughts on the world, or to study their projects as precedent. On the other hand, there were many slave holders celebrated. Thomas Jefferson was presented unproblematically for his brilliant innovations in landscape design. And so I was perpetually, in those three years, very lost about my place in this profession. In fact, I took a year off and went to work for Walter Hood and came back having more confidence in my ability to see myself in this profession and understanding about how my experience in the world can influence design. Because, otherwise, when I would ask certain questions in school, it was often met with, “You’re in landscape architecture; why would you bring that up?”

In my third year, we had a guest lecturer in our “Professional Practice” class who, in passing, mentioned that Olmsted visited the South. That was the first I had ever heard of that. We had already learned a lot about Olmsted, but I had never heard that he traveled through the South to write about the conditions of slavery. I followed up with the guest lecturer, and with my two professors—I still have this email. I often revisit that email chain because it has led me to this point in my research. I asked for further reading material about Olmsted’s travels and they sent me a reference, but what I really wanted was to be able to reflect on the connection between his abolitionist thoughts and his practice of landscape architecture.

If that book had existed, I would have read the book and kept moving on with my life. But it didn’t exist and I couldn’t resolve the fact that this had never been brought to my attention, and how much we could possibly learn from mining this part of Olmsted’s biography.

So, I got a fellowship and spent four months at Dumbarton Oaks researching this. After that, I spent three months in a car retracing his steps through the South. I proposed, as part of my research methodology, that visiting the sites would offer some reflections on the relevance of Olmsted’s travels and the profession today. Now, I’m writing those reflections into a book.

The seminar I am teaching this semester investigates Olmsted’s original writings on the South not only as a historical document, but as a methodological proposition. The students develop research and representational methods to make assertions about the factors underlying the change witnessed on the site over the course of the past 165 years, since Olmsted’s visit.

Because ultimately, I think Olmsted’s story has implications for what our practice of landscape architecture can be today. I think that looking at the places he visited and taking stock of the changes they’ve undergone, as well as the ways they’ve stayed the same, presents opportunities for considering the potential of contemporary landscape architecture and methods.

KH There is a persistent question of relevance felt within the field, and maybe even perceived by outsiders, but in either case, it is not always clear what our fundamentals are. What has researching the methods used by Olmsted prior to entering landscape architecture revealed to you about our foundations, and why should this text be a grounding force in contemporary landscape architecture?

SZ It actually starts with challenging the idea that this was something that he did before landscape architecture. What my research is revealing to me is that they were actually simultaneous endeavors in a way, not subsequent to one another. In fact, he steps down from his position as superintendent of Central Park in order to rewrite his work about the South and republish it. It is not a fair portrayal of Olmsted to hold these endeavors of his separately.

What was powerful about Olmsted, and can be seen in this text, was his way of being able to toggle between a site and into its larger economic, social, and ecological dynamics. We have hundreds of pages of Olmsted in conversation with enslaved people where he took extra care to record dialect. He takes great care to record details of light qualities, topography, tree species, and soil conditions. He was very tuned into the here and now, and at the same moment, engaged in analysis of the underlying macroeconomics, macropolitics, and macroecologies of each place. This carried forward into his practice of landscape architecture where he thinks in a very material way, but always in the context of the wider concerns of society.

Something happened in the transition from Olmsted Sr. to the next generation of landscape architects. The wider range of concerns fell away and the idea of landscape architects as technicians took hold essentially. The reality is that shaping landscapes is a very powerful tool. To wield that power without an understanding of the larger context or an acknowledgement or sensitivity or methods, there’s a lot of damage that can be done. It’s an incredible power, right? We have decades of landscape architecture, architecture, and urban planning that demonstrate what kind of damage can be done if you don’t have the proper methods or considerations. So, it’s interesting to see how landscape architecture is grappling with its relevance in these contexts of late, whether environmental, ecological, social, political, or economic. Some of the answers may be found in the origin story of the profession, if we claim The Cotton Kingdom as part of it, as I aim to do with my book.

I’m perplexed as to why landscape architecture has avoided historicizing this text as part of its origin story. In fact, landscape architects often reference Walks and Talks of an American Farmer in England, which predates The Cotton Kingdom. So, you could argue it’s less relevant to Olmsted’s practice of landscape architecture, but it’s in England, so maybe that is easier to talk about, if you assume that’s why. But I will say that among historians, Olmsted is considered the most cited witness of slavery in the 19th century. There’s no doubt about the significance of Olmsted’s writing in the South in history. It is landscape architects who are kind of quiet about it.

KH It was so surprising to find that Malcolm X cited this writing as one that was influential to him. This idea that a landscape architect could create anything that would be found relevant to someone like Malcolm X is incredible.

SZ Yeah! Like, Olmsted might have sparked the career of one of the foremost activists in the civil rights era? What?

KH Yeah, unbelievable.

SZ Without Olmsted, we may not have had an awakened Malcolm X to spark Black nationalism and all of these important Black philosophical frameworks.

KH But now, we just pass over this book. When you consider that the field never truly embraced this writing, even from a canonical figure like Olmsted, but did embrace writings that termed the field as being one of, “the polite arts,” like Humphrey Repton’s Art of Landscape Gardening, for example, it produces a jarring realization about our blind spots; the parts of our history that we’re able to handle and that which we are not.

SZ Yeah, exactly. The English were a major part of the transatlantic slave trade. Where was all that capital coming from that would fuel the Picturesque movement? Because the Picturesque was all about labor and this dominion over the landscape that slavery was honestly a major driver of. And so to me, you can’t separate all of these movements in Europe from the history of slavery, dispossession, and colonization.

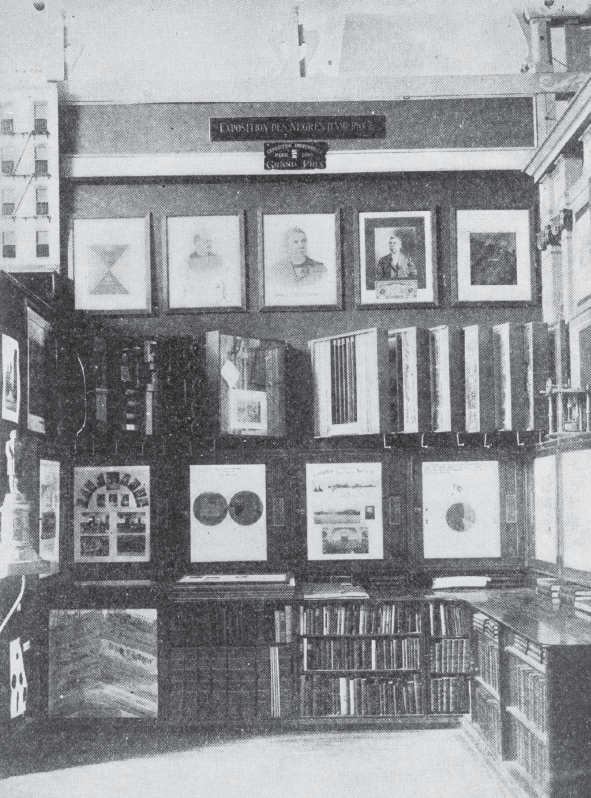

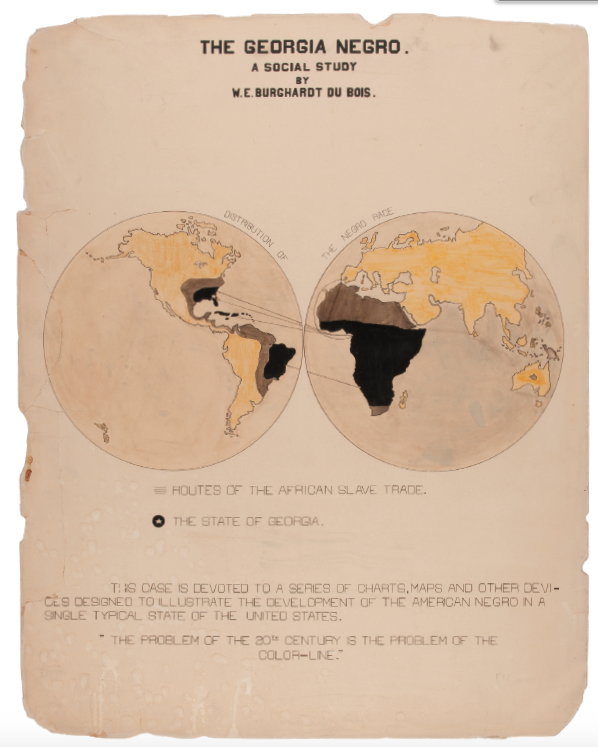

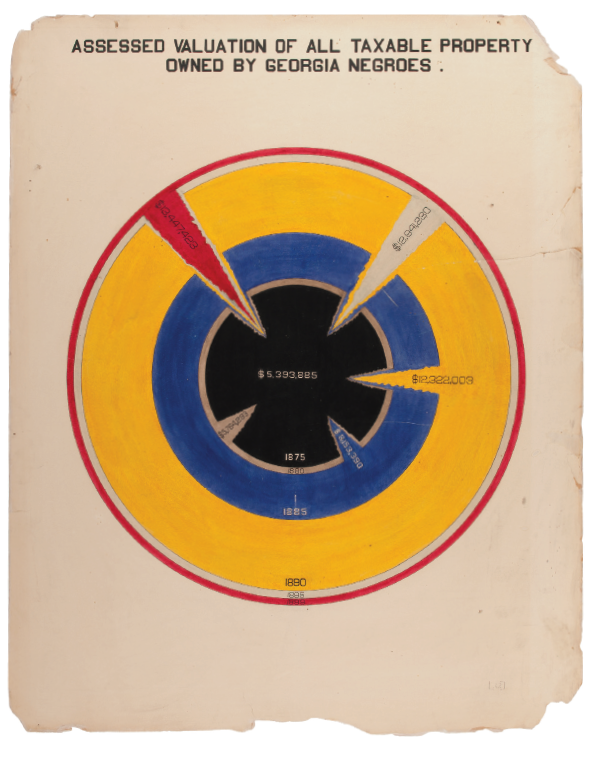

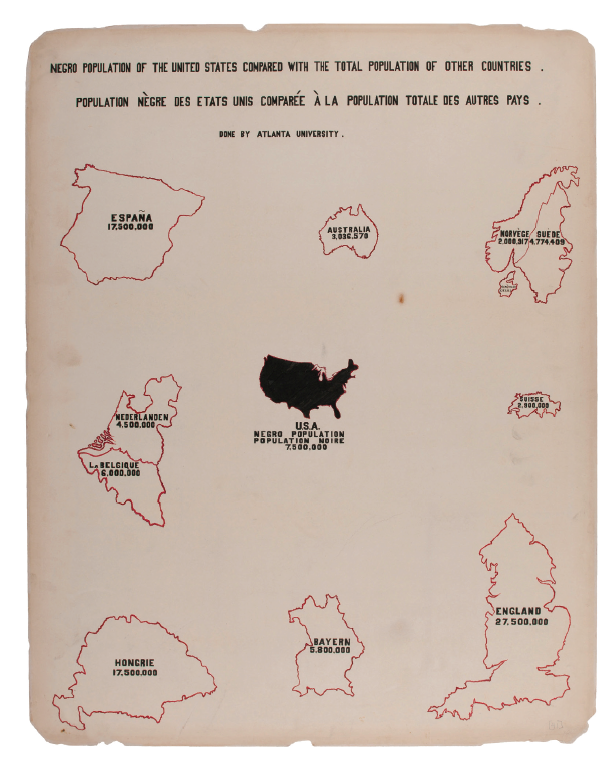

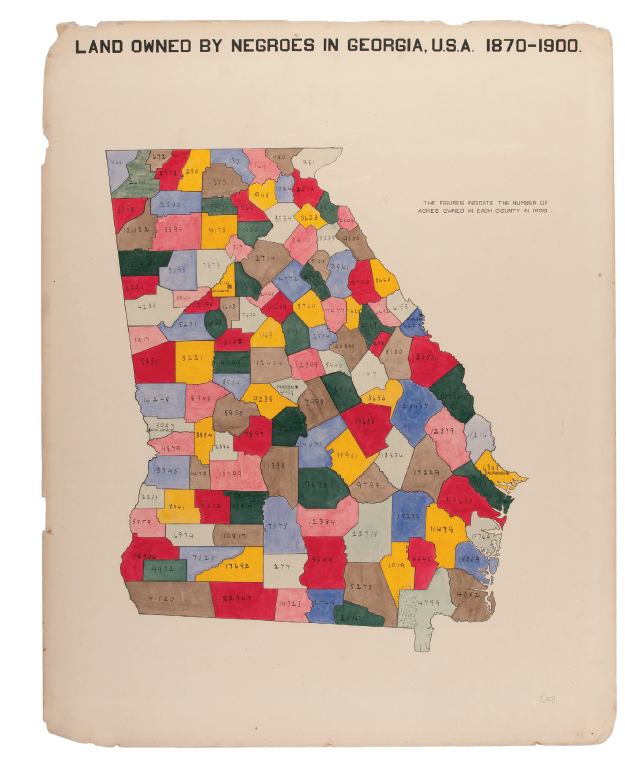

KH In The Cotton Kingdom, there is one map that takes what is otherwise an argument made in a long and complex text, and summarizes the research as simply and succinctly as possible through its spatial reality. It illuminates connections. How might this drawing stand in relation to the data portraits of W. E. B. Du Bois’s Paris Exhibition of 1900? Both of these documents together convey some sense of the realities in the United States immediately before and 37 years after abolition. There is a lot that can be said about these documents that is difficult in such a short time, but broadly, what does the pairing of these drawings make you think of given your research, your practice, and your background in sociology?

SZ One thing that we’ve been talking about in class is the idea of both representivity and singularity. Black literature in the United States is really birthed in the idea of the slave narrative and people writing their personal experiences of being enslaved. We just read a Toni Morrison essay called “The Site of Memory,” where she explains the challenge of Black literature, which is to both express and articulate the specifics, the singularity of experience: “This happened to me. This is my story.” But at the same time as they’re expressing their singular experience, these authors would try to reflect a representivity. In other words: “This is happening to me, but imagine the scale at which this is happening to other people—millions of them—broadly, who are enslaved and/or oppressed.” It was always a dual mode in which they wrote.

Olmsted and a man named Daniel Goodloe made the map you are referencing to be included in the third publishing of the writings, which was his most staunchly abolitionist editing of the work. The book is structured with the large macro-conclusions as bookends to the travel notes in the middle chapters. The travel notes are all about that singularity: I went here. I had this conversation. This site, this site, this site. But then the intro and the conclusion chapters are about that representivity, making large-scale analyses of the region. This map is included in that.

Du Bois too. Du Bois has these sociological studies where he spends time in a very specific Philadelphia neighborhood, for instance, and is doing very similar qualitative analysis of singularity, but at the same time is toggling out to this sort of representative mode of working, which his drawings reflect.

And so both Olmsted and Du Bois are grappling with the productive space between representativity and singularity. That is, in my mind, one of the biggest takeaways for landscape architects whereas we generally work more exclusively in the singular, site-scale mode. Both Du Bois and Olmsted work between the two as social scientists, designers and journalists, but are also evolving those methods. It’s interesting. It’s compelling to pair the two in that way.

KH I’d also like to point out that you share this point of comparison with the two. Du Bois was, among many things, a social scientist; Olmsted operated as a social scientist; and you yourself have a background in sociology and statistics prior to entering design. What was it that sparked this transition in you?

SZ Yeah, I’m realizing that’s not very common. Most of my friendsand colleagues entered into design from another creative field, but I read my way into design. Reading Du Bois, Lefebvre, de Certeau, and bell hooks, I just became fascinated with the spatial dimensions of this social world they’re so interested in. So, from sociology, I went to city planning, and more and more inched my way into landscape architecture.

What I take away from sociology is the methods question. I think there’s something productive about that for designers. I believe we need to have a discourse on methods that we’re testing and evolving if we’re going to engage with major issues beyond the silo of our discipline. It is a question of balance. How do we keep design and research as a culture and tradition that’s productive for us but, at the same time, are able to ask other people to hold us accountable? That’s something that I bring from sociology into my work as a landscape architect.

KH Given that, what does an ideal practice look like to you?

SZ I think research and exploratory work integrated into the process of building landscapes is important in an ideal practice, but finding the appropriate financial mechanisms to support this in private practice is something we’re testing right now in my office.

We really push in the scope for a heavy front-end that is engaged politically and with community members. And, if I find myself in a room with elected officials or civic leaders or philanthropists, I try to make the case for creating funding opportunities for designers to get involved in work that happens before an RFP: the shaping of an RFP, the shaping of its scope, the strategizing around investment.

That’s what we learned at the GSD. Landscape architecture at the GSD is taught in a multi-scalar fashion, and often the students are positioned to identify their site and their project, which are the skills you need to be an advocate. Advocacy is embedded in the scales that we’re working in the Landscape Architecture department at the GSD. And we sort of accept that this mode of working and thinking ends when you leave the GSD, but I would like to see expanded formats for us to employ those methods and tools in the real world.

KH Olmsted wasn’t a passive participant in his time as a young journalist. Through this document, he was actively advocating for the abolition of slavery and rushing to complete and publish it in time to shape the minds of a very divided country on the brink of civil war. In a contentious context and on a charged topic, he builds his argument in opposition from an economic point of view. What do you think of this choice?

SZ It’s funny. This is often a conversation of fierce debate in the class. Is Olmsted’s voice adaptive? He writes about slavery with a very matter-of-fact tone about issues and observations that are anything but. Speaking personally on my own behalf, I feel that this can be productive when working in highly charged contexts. In my practice, we work on a lot of sites with contested narratives—very charged sites. I often find that it is productive to keep things matter-of-fact, just to keep projects moving and going, and not to repel anyone who might actually gain some knowledge from listening to the conversation. You have to be strategic about when you use a different tone and when it might be effective.

Olmsted talks about this in his personal letters—that he does want to have slave owners in the South as an audience. He wants to convince them. He wants to challenge their logic about slavery. He does aspire to that. As the years go on he became less convinced that it’s even possible, and then comes to the conclusion when he rewrites for The Cotton Kingdom, “Subjugation is the only way we can bring the South into giving in with the North and rid them of slavery.” Basically, war is the only way that this is going to get solved. He’s just like, “There’s no talking to these people.”

But that was his intention initially with his tone, and he was explicit about that. I think that there’s something there, especially if you live a life within the implications of this history every day. Then there is a kind of matter-of-factness to these topics that you have to rely on in order to just live your life every day. Being overtaken emotionally by this is somewhat of a privilege, because you can do that and then go back to your regular life. But if you’re thinking about it every day, and you don’t have a choice about that, that’s where matter-of-factness is less disturbing, because it’s life. It’s everyday life. It is your life.

KH Because urban planners, architects, and landscape architects are working in public spaces, the work has an inherently political element. As you said earlier, you really wield a power in the ability to shape land. So, I am curious about how you view politics and design.

If we don’t silo Olmsted-as-a-political-writer from Olmsted-as-a-designer, then there is something exciting in seeing someone successfully synthesize politics and design into one—research and practice into one. Your practice is also managing to synthesize social research and design in ways that are exciting to see, given how many students and young professionals struggle to do both well.

When it comes to effectively engaging social issues, are there some things that you achieve as a politically engaged citizen that you can’t through design?

SZ One thing that we aim to do in my office is synthesize our social and cultural analyses with detail and construction. Those larger understandings of work can and should influence a landscape’s material expression. The built landscape is ultimately what makes people feel like they belong. In this way, a garden is just as political as a large-scale, regional infrastructure project.

What is it that was built and how does it feel to be in it? Is it acknowledging and supportive of my well-being or is it not? Does it feel reflective of my identity or not?

And so I hope that the suggestion here about understanding the macro is not the conclusion reached. I think the actual building of things at any scale is important, and given Olmsted’s level of detailed involvement in writing as well as building landscapes, I would say he shares that.

So, I would say they are separate, but I don’t think of a citizen and designer as entirely different. I guess I haven’t really thought of that distinction. Part of this is due to the fact that there are only 12 or 13 licensed Black women in landscape architecture in America.

KH Wow.

SZ Isn’t that crazy? It’s insane.

And so just being a landscape architect in my case is often politicized by people. They project things onto me. I often don’t have the luxury of separating the two. I’m always asked, “How did your experiences in life influence your landscape?” People project that, and so that separation is not afforded to me.

In reality, probably nobody can separate the two, but other people are never or rarely asked to articulate the connection between who they are and what they do. Have you ever heard somebody on a panel or a lecture say, “How has being a white male influenced the way in which you work as a designer?” Nobody ever asks that. And I always, every single day, get that question.

I think reflecting on the inextricable nature between who you are as a person, as a citizen, and how you work as a designer should be reflected on by everyone, not just people of color or women.

KH Designers are working in a particularly entangled reality. With the entirety of Olmsted’s career in view, what lessons of what to do and what not to do might we learn?

SZ Well, Olmsted was 31 when he went on this journey, which is the same age as a lot of people at the GSD.

KH That’s a great point.

SZ There’s a boldness to what he does. He is a very confident person. There is a boldness and an ability to envision his role and his impact in the world at a young age that is something to admire. And I think for me as Black woman, born and raised in the South, I had to do some of that too: envisioning things that don’t really exist in order to be where I am at, to have an office, to be on the faculty at a school like the GSD; these are things that I did not see. I didn’t even know landscape architecture existed until, frankly, relatively recently.

It’s kind of crazy, but I guess dreaming big and doing what you profess is a lesson we can all take away from his career in view. In his personal letters as early as age 22, he would often write to friends about his ambitions: “I don’t know what I’m going to do with my life, but I do know that I want to do big things. There are a lot of really big issues in the country, and I have this knowledge of the land and agriculture, but I’m also interested in politics.” And he’s just like, “What is this thing? How do I do this? How do I bring these things together? I want to make an impact.” And that’s the energy that our profession was founded on.

KH It’s a beautiful idea. And it never gets old to find these writings of almost mythological figures when they were young and they’re just like, “I have no idea what I’m doing.” [laughs] It is always a relief.

SZ [laughs] Yes . . . Ah, I feel like Fred and I are old friends.

Pairs is co-founded by Kimberley Huggins (MLA I ’20), Nicolás Delgado Alcega (MArch II ’20), and Vladimir Gintoff (MArch I ’21, MUP ’21), and supported by Dean Sarah M. Whiting and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.