When asked about the theoretical touchstones for his new studio, “The Black New Deal,” Design Critic Bryan C. Lee references almost exclusively the work of Black liberation thinkers and activists: Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois, Black abolitionists, and leaders of the Black Panther Party and the Black Lives Matter Movement. Each understood the importance of space, place, and community-building in determining the overall condition of Black people in America.

Lee is a practitioner of Design Justice, a movement to eradicate structural inequalities in design to create spaces of racial, social, and cultural equality. Its members include a growing cohort of architects, urbanists, and planners who are also deeply engaged in social justice discourse. They are as concerned with the societal impact of a designed product as with how it came into being. Traditionally marginalized communities are not just consulted—they lead the creative process in a collaborative exchange with designers.

Who holds power in a particular condition? What is the injustice that results from that power? Who is directly and disproportionately impacted by that injustice? How does it physically manifest in the built environment? And where are the opportunities to challenge those systems and envision new ones that actually serve those who have been impacted by those injustices?

On the five questions that guide his pedagogical approach

“The Black New Deal,” which was introduced at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in spring 2021, prepares students to develop a professional practice that interrogates space using an anti-racist lens. In conversation, Lee cites the five questions that guide his pedagogical approach and his professional work as founder of Colloqate Design, a nonprofit multidisciplinary studio in New Orleans: Who holds power in a particular condition? What is the injustice that results from that power? Who is directly and disproportionately impacted by that injustice? How does it physically manifest in the built environment? And where are the opportunities to challenge those systems and envision new ones that actually serve those who have been impacted by those injustices?

To appreciate the need for courses like “The Black New Deal,” it helps to understand what they are responding to. Lee points to examples from history where space and design have been used to propagate racial oppression. He cites policies that govern land and its use—forcibly removing Black people from it or forcing them to work it for free; the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision that upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation in public spaces; legal or de facto segregation that limits where Black people can live or generate wealth through home ownership; the crime prevention through environmental design agenda of the 1970s that used the built environment to establish a police state in urban areas; the slashing of the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s budgets in the 1980s that effectively ended the affordable housing program; and something as everyday as a design studio parachuting in to develop a site without acknowledging local realities.

“What Design Justice is asking us to do first is to challenge the privilege of power structures that use architecture and design as a tool of oppression,” Lee says by way of explaining how to spot structural inequality. “We have to recognize the combinatorial condition of policies, procedures, pedagogy, practice, projects, and people as methods for using the built environment to maintain systems of power.”

During the course module, studio time is divided between studying the connection between racial and spatial violence, and community engagement methodologies. There are weekly guest lectures from members of the community—organizers, advocates, activists, artists, and elected officials. “They are invited to be a part of the conversation,” Lee says, “not just to be extracted from, but to get feedback from and for them to express their likes, dislikes, and narratives.”

The course culminates in a community-based project. There are important parameters: Students can collaborate, but final projects are individual. The design site must be within Trenton, New Jersey, because it is Lee’s hometown and a place where he can support students as they link up with the local community. Finally, students will be graded not on the standard GSD criteria, Lee cautions, but rather on the extent to which they have privileged the meaningful inclusion of the community voice in the final product. After all, according to the course description, the studio “is an exercise in deep listening and cultural understanding.”

“The Black New Deal” focuses on eradicating harmful practices as well on imagining what could come in their place. Design Justice is ultimately future-facing, envisioning a reality in which design not only ceases to be a deterrent to Black advancement but becomes an agent in its realization.

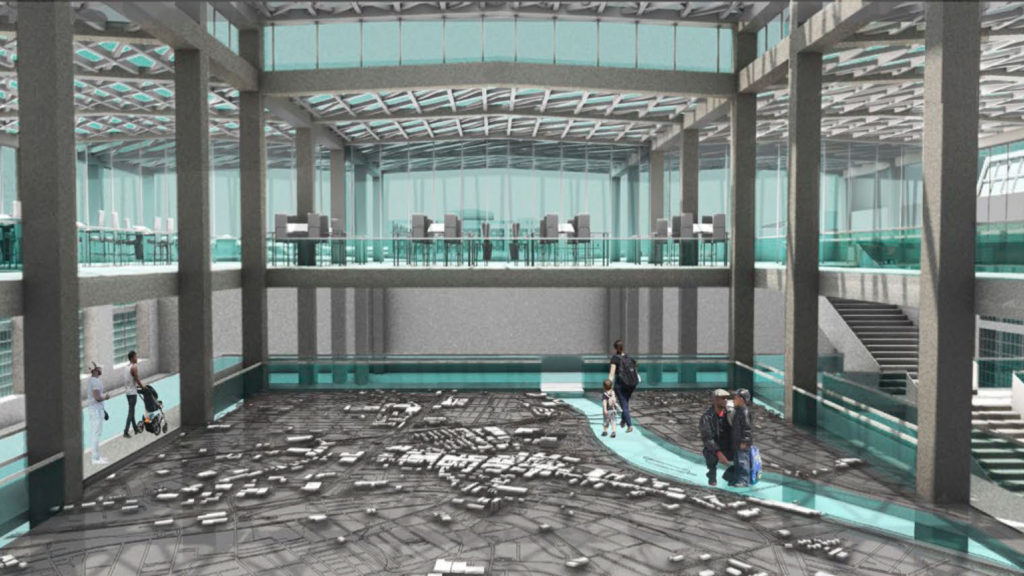

The first time Lee taught the course, blueprints emerged for these “new typologies of liberation,” as he calls them. One student’s project involved abandoning the New Jersey governor’s mansion in Princeton, a space rarely used by governors. Inspired by a call once issued by the Black Panthers to eliminate the executive branch, Edward Wang (MArch ’22) adopted a similarly radical response to New Jersey’s governors. To challenge their outsized political influence—as embodied in the unoccupied mansion—Wang proposed instead locating an “Office of Governors” in Trenton, for those who govern at the neighborhood level and catering to the needs of everyday people. An official state structure is thus transformed from a seat of exclusive political power into a democratic house of public service and pluralistic representation.

Wang’s project exemplifies the concept of mutual aid—a dependence on and obligation to one another for social and political progress. It is another of the foundational tenets of Design Justice, borrowing from the central role of mutualism in social movements for more than 200 years, from safe houses that gave refuge to enslaved people escaping along the Underground Railroad, to the Black Panther Party’s free lunch and breakfast programs, to mutual aid organizations that have cropped up during the current pandemic.

Lee explains how the ideals of mutualism come to bear on his approach to the course: “Architecture that scaffolds and supports notions of mutualism is something that we’re seeking to pronounce as valuable. When we look for some version of liberation in the built environment, we’re really seeking to understand the collective narratives of place.” He continues, “Acknowledging a collective narrative and history centers us so that we can move to a point where we are creating spaces of mutual aid. That kind of mutuality is necessary for the built environment to actually serve the broader community more than it currently does.”

Lee takes a deep, contemplative breath when asked about the course name. It comes from the association he makes between the ideals of the New Deal of the 1930s and the failed but audacious promise of the Freedmen’s Bureau. A short-lived government agency established following the Civil War, the bureau was tasked with providing land, health care, food, education, stable jobs, and decent housing to nearly 4 million formerly enslaved people in the South. To Lee’s mind, the Freedmen’s Bureau—which was abandoned by Congress in 1872—could have been the most radical and revolutionary New Deal premise ever imagined for Black people.

The course then asks, If we were to bring that premise forward to today, what would it look like in the built environment? Lee says, “How do we translate the collection of demands that exist in movements that wrapped themselves around those same set of principles into design? It is about holding ourselves to a contemporary understanding of what the Freedmen’s Bureau was attempting to do and trying to see what it might look like if we were to win these battles.”

For students, potentially the most challenging aspect of the studio is that the work of dismantling extends to—or starts with—their own ideology. Western culture teaches us to privilege the individual idea as, Lee says. That can make it difficult for students to acknowledge and eliminate internalized white supremacy and become radical in how they view the social ramifications of their work. Similarly, it can be hard for them to understand the pain and traumas of communities if there is no precedent in own their lives. The risk is that, in the absence of a personal experience, they will revert to standard operating procedures.

In this sense, the course is highly ambitious. Its sphere of influence aspires to move from the unconscious biases of budding designers, to their conscious creative practice, out to the lives of individuals often disconnected from having a say in the shape of their environment, and on to fueling a movement for systemic change. Indeed, the work of Design Justice is itself monumental. That is made clear by Lee’s argument that while not every designed space has a role in propagating oppression, most are somehow implicated.

“There are spaces that don’t have injustice inherently built into them. But there are very few that don’t inherently have prejudice or bias built into them. And the threshold to which bias becomes injustice is very thin,” he explains. In that sense, almost the entirety of our built world is up for scrutiny. Module by module, at the GSD and beyond, the army of well-trained scrutinizers is growing.