“Yet what we need is a voluntary cessation, a conscious and fully consensual interruption. Without which there will be no tomorrow.”1

The concept of sustainable construction does not hold meaning any longer. Real sustainability is an impossible endeavor and a delusion in the present modus operandi of global construction. From land consumption to material use, building is a destructive process: urbanization devours hectares of unbuilt land every year, and the construction industry relies intensively on resource extraction.2 Through mining, manufacturing, and building, the energy used in construction impacts the planet at a tectonic scale. Water bodies, ecosystems, topography, geology, climate, food systems, labor conditions, humans, and nonhumans everywhere are destroyed or damaged to propel voracious global supply chains.

The end of the world has been ongoing for many. From the tons of toxic bauxite residue stored in unstable pools in Hungary to the devastated social landscapes surrounding the coltan mines of Chile, this damage is a prerequisite of designed spaces, affecting all non-constructed surfaces—from forest to farmland.3 Despite loud calls to reexamine our faulty growth model, the expansionist global enterprise of land and resource exhaustion fueled by both construction and real estate development goes on relentlessly.4

Stop Building?

The call for a moratorium on new construction emerges from these global urgencies and from the palpable lack of action on the side of the building industry and planning disciplines beyond flaccid corporate strategies (green labeling, carbon compensation, material reinvention, and LEED, for example). Devised to cover up ongoing devastation, construction’s greenwashing of its toll on the environment is deployed in full force. Little is done to curb the damage done through commodified and speculative real estate development and construction schemes. Moreover, global material use is expected to rebound with post-pandemic economic policies and to double by 2060; a third of this rise is attributable to construction materials.

And this is but a fraction of what ultimately makes up the built environment. The transformation of raw resources into exploitable architectural elements (aggregates to concrete; sand and silica to glass; petroleum to insulation foam) not only necessitates the combustion of fossil fuel at every turn, but also relies on a host of facilitating technologies. Automated mining systems and computer-aided drawing software, for example, steer an increase in the extraction of critical minerals including aluminum, cobalt, copper, graphite, lithium, manganese, nickel, platinum, tin, titanium, tungsten, and zinc, among others.

The front lines of extraction are moving in all directions, and rapid devastation is ongoing. Paradoxically described as unavoidably necessary in order to transition to less carbon-intensive lifestyles in selected parts of the planet, this commodity shift toward rare materials suggests that sustainable oil rigs and e-Caterpillars will be undertaking the greener enterprise of destruction we design.

Against the propagandizing of ecological concerns both for eco-fascist agendas and as a business driver of technofixes, a moratorium on new construction calls for a drastic change to building protocols while seeking to articulate a radical thinking framework to work out alternatives.

House Everyone

Because housing is a human right and the mandate of the design disciplines, our fields stand at the difficult threshold between housing provision and devastation: How does one navigate the need for housing as well as the destructive practice of its construction? According to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) census of 2021, the median size of new single-family homes was 2,273 square feet, compared to 1,500 square feet in the 1960s, despite the shrinking of the median household size, down from 3.29 in the 1960s to 2.52 persons today.5 This trend sees more land, more materials, more appliances, and more infrastructures directed toward larger homes built to host fewer people, with debt at the core of its financing. In a talk at the GSD in February 2022, HUD secretary Marcia L. Fudge said that the days when one can have a plot to build a house were numbered—despite her lecture being titled “Building the World We Want to See.”6

If we jettison the maxim that the solution to the housing crisis is to build, myriad other possibilities come into view: decent minimum living wages, just protocols to housing access, rent control, zoning reforms, purchase of private property to provide public housing, fostering of collective ownership and forms of cohabitation, and alternative value generation schemes. These solutions allow us to move beyond the struggles and dichotomies that plague the debate: renting vs. ownership, YIMBYs vs. NIMBYs, nature vs. humans, and housing crisis mitigation vs. zero net emission, among others.

If new construction were to stop completely, even for a short while, the current built stock—buildings, infrastructure, materials—would have to be reassessed, and the productive and reproductive labor that goes into it necessarily would be revalued. Varying widely from well-paid skilled workers to exploited manual laborers, the labor force involved in construction remains mainly unautomated—and overlooked. We could anticipate the emergence of new societal and ecological values and a reevaluation of the labor involved in caring for buildings, from surveying the existing stock to engaging in reparative works to acts of daily upkeep.7

The effort ahead is immense; a different way of designing the world emerges, one that demands a careful assessment of present and vacant inventory, strong policies on occupancy and against demolition, anti-vacancy measures, densification plans, maintenance protocols, end-of-life etiquette for materials, and overall upgrading tactics. These will all need to be imagined, formulated, planned, and implemented—according to the needs of the context.

Who Is to Say Build or not Build?

At the same time, a moratorium’s global validity must be interrogated. The geography of harmful extraction and the political economy of construction are mirrored in today’s neocolonial modes of extraction capitalism, with gendered and racialized populations most affected. Assuming that the bauxite extracted in Guinea ends up on the facades of pencil towers in New York, shouldn’t a moratorium be limited to new construction where a consolidated stock already exists? Indeed, the integrity of the sustainability narrative is belied by the extent to which environmental laws have been successfully weaponized and how unpersuasive frugality arguments continue to be.

As Peter Marcuse argues, “the promotion of ‘sustainability’ may simply encourage the sustaining of the unjust status quo and how the attempt to suggest that everyone has common interests in ‘sustainable urban development’ masks very real conflicts of interest.”8 Achille Mbembe spells it out: “In Africa especially, but in many places in the Global South, energy-intensive extraction, agricultural expansion, predatory sales of land, and destruction of forests will continue unabated.”9 Thus, with overbuilding and resource consumption on one side and lack of housing and material extraction on the other, a new construction moratorium could be restricted to extractive built nations and adopted by countries incrementally along GDP lines.

Upon closer inspection, the need for nuance emerges. In Cairo, there are 12 million vacant units, high vacancy rates grounded in locally specific conditions such as questionable rent control laws, proactive suburban development state programs, and a lack of trust in banking institutions.10 In Costa Rica, the bulk of new construction consists of coastal residential units aimed at tourists or expatriates, fueling socio-environmental issues of displacement and degradation.11 In South Africa, the demolition of scarce public housing to make way for market-rate units shows the limitation of the construction-as-solution storyline.12

Nevertheless, building more is heralded everywhere as the sole answer, a debatable leitmotif served up from the Bay Area to Mumbai that conceals the reality of the commodification of housing fueled by debt financing. Housing needs are not the question when home insecurity is such an acute problem for many, and when it is true that crucial infrastructures are lacking in some regions.13 Thus, construction is not to be condemned outright when there are such vast disparities in what different countries can provide. But while contextual complexities require a deeper investigation into where and what is constructed and what should not be built, a moratorium on new construction challenges the incapacity of the sector to envision alternative large-scale housing provision schemes beyond building new.

Beyond GDPs and other faulty measurements, beyond moral confines and neo-Malthusian indictments, how are we to grapple with sustainability as a contested concept, legacies of degrowth theory, green capitalism, and problematic CO2 reduction policies becoming the stuff of riots?14 How many of the thousands of new housing units built every year everywhere are accessible to those who need them most? How can we optimize and maximize our existing stock before extracting new materials? How do the design disciplines face their complicit role in environmental degradation, social injustice, and climate crisis, and challenge the current system of global construction?

Imagining Possibilities

The following vignettes play out in various locations to answer some of these interrogations. Drawing from A Moratorium on New Construction, an option studio that took place at the GSD in spring 2022, these ideas point to what must stop and what needs to change, from India to the United States. In contemplating redistributive modes of ownership and communing and questioning the standard claim of building right, predatory real estate practices, high-tech-heavy solutions, and the assumption that architects must build anew rather than practice methods of repair and prolonging, a vision for a material future relying on our current built stock emerges.

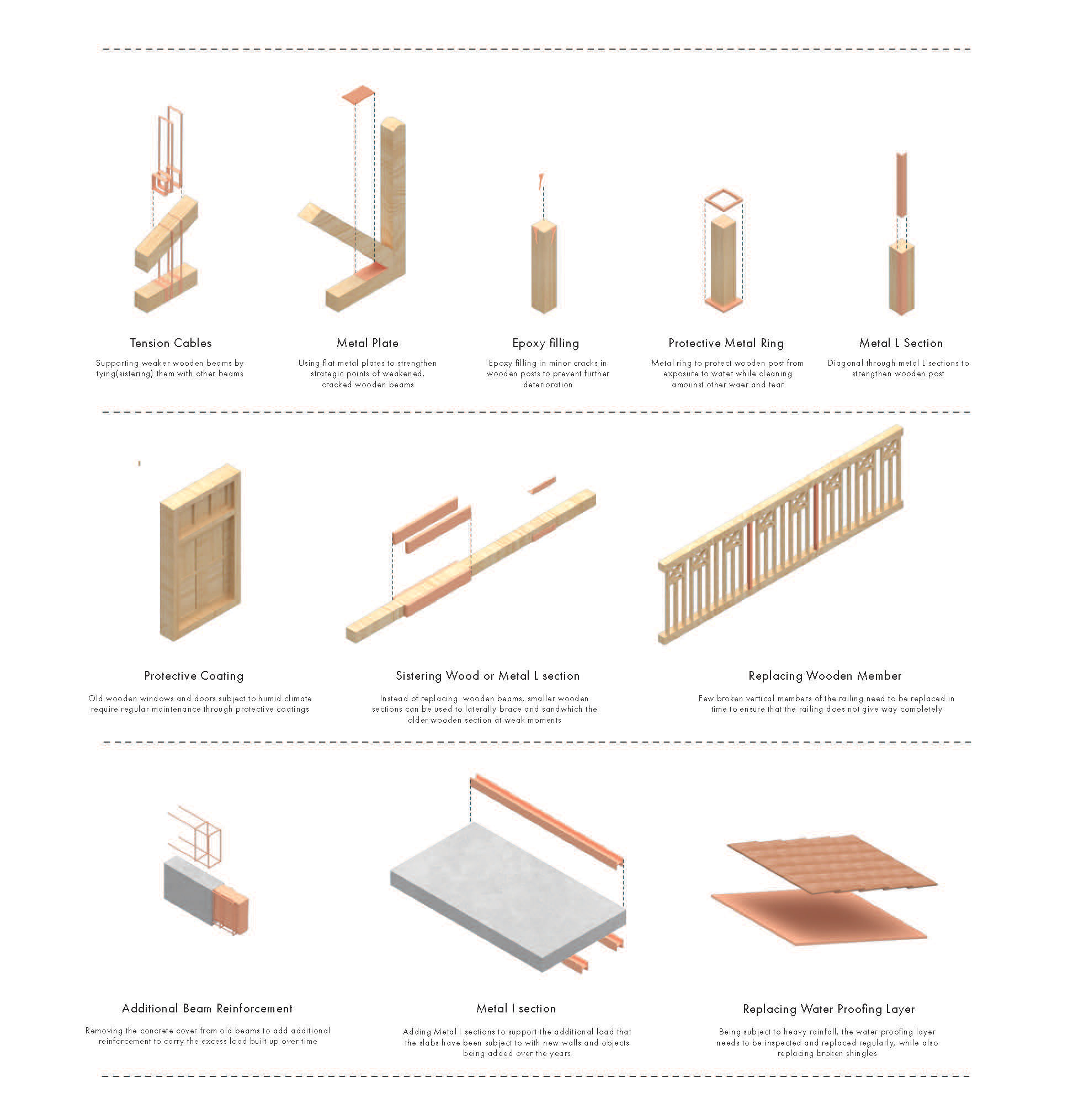

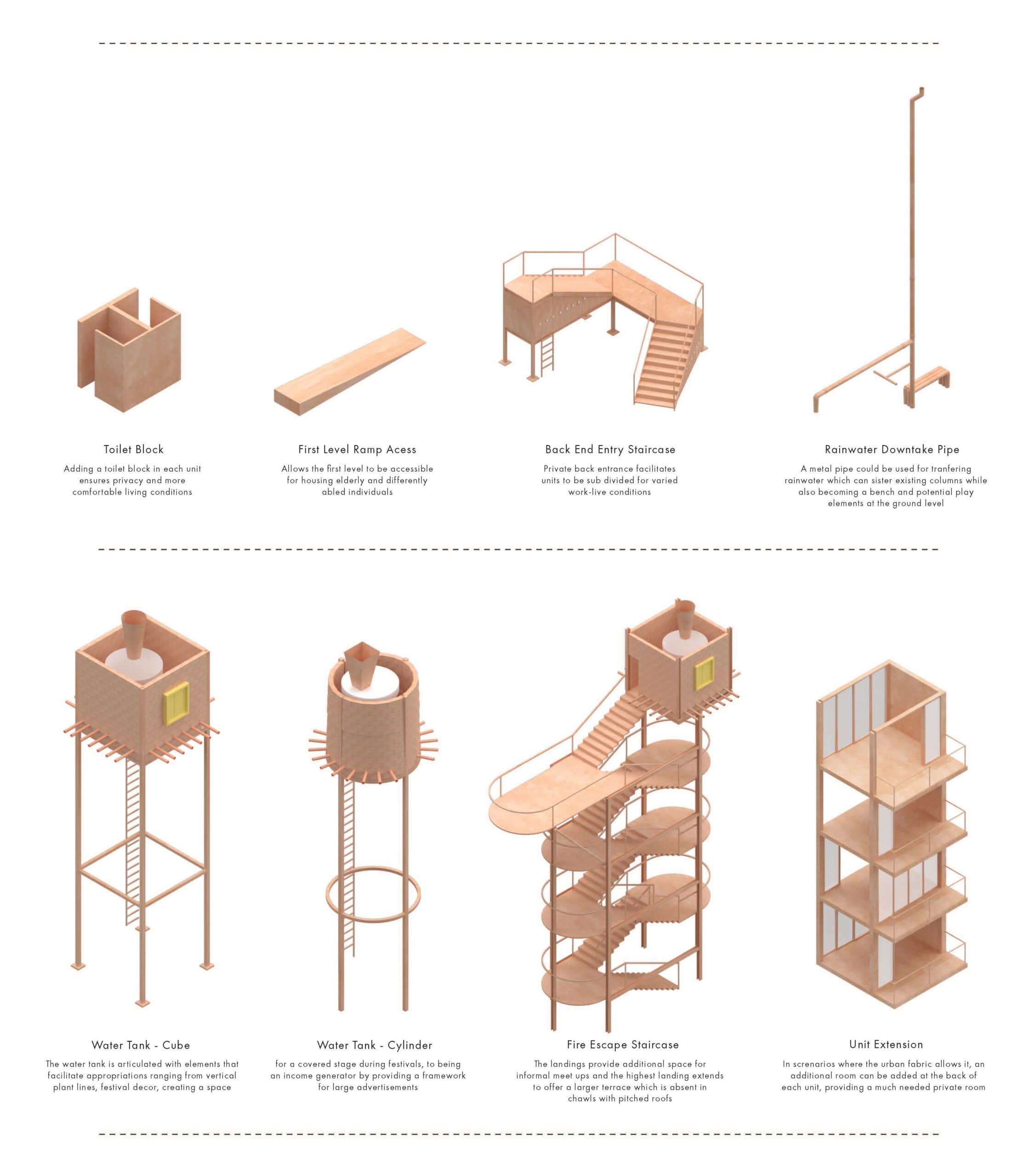

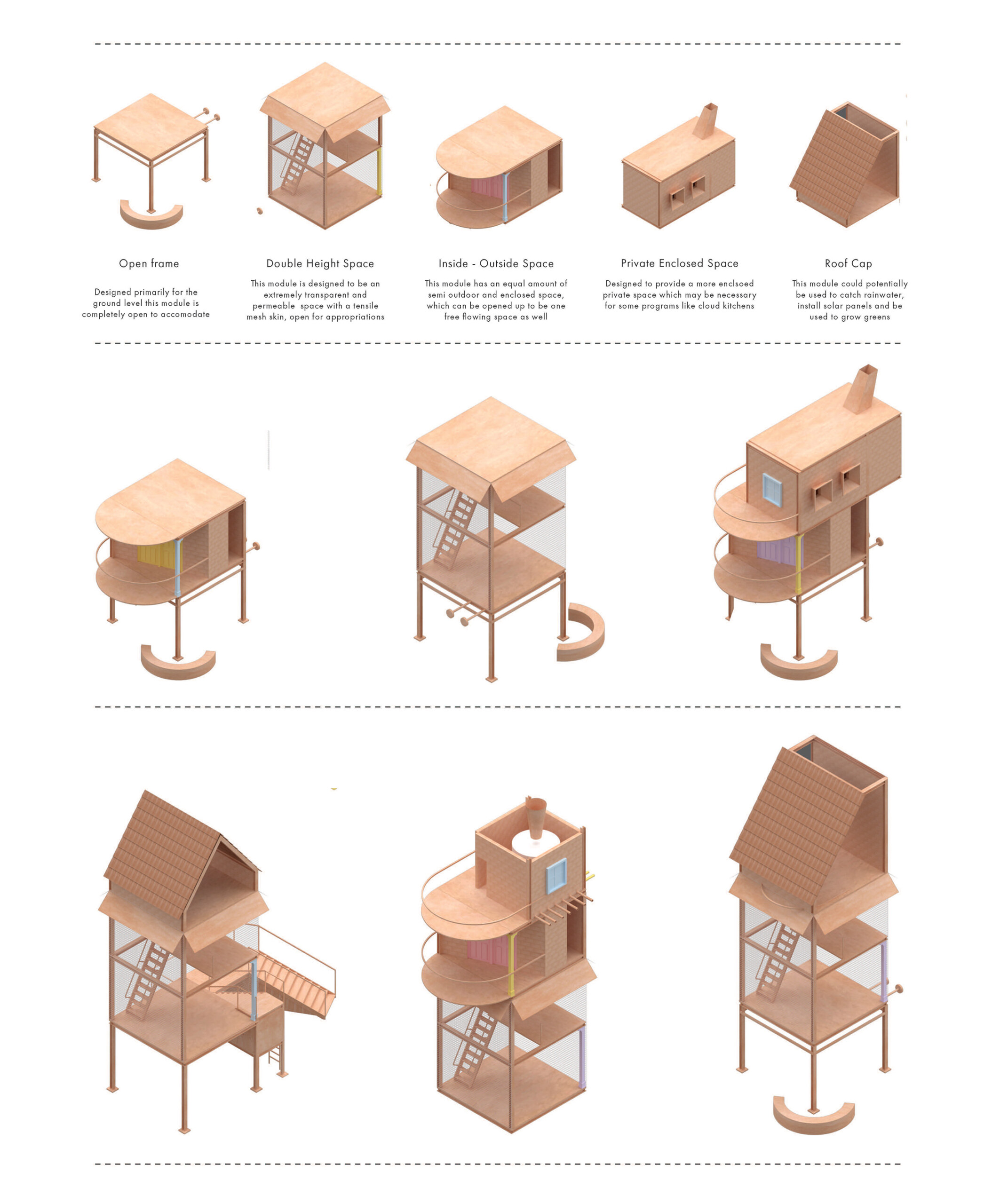

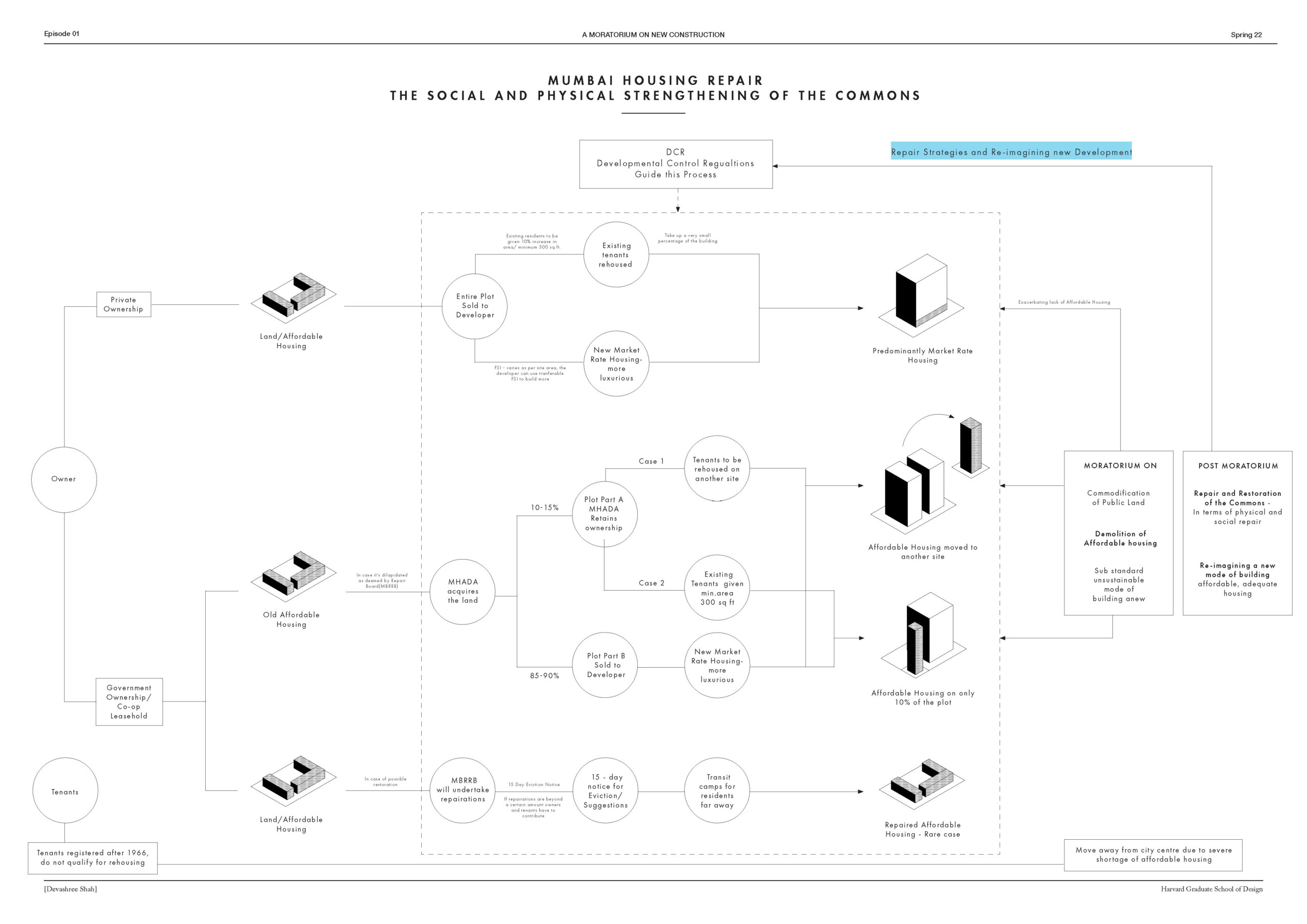

In Mumbai, a city where affordable housing is in high demand, the ongoing demise of chawls—collective units built in the 1930s for mill workers, and now home to active but modest communities—epitomizes the rapid destruction of affordable housing at the hands of the state and the private sector. High-rises for wealthier owners replace the chawls, and the tenants are displaced. Devashree Shah (MArch ’22) argues for a moratorium on the demolition of chawls and all subsequent new construction. But because aging chawls’ structures require upkeep, Shah proposes a post-moratorium design strategy that envisions physical and social repair as a unified design task.

From maintenance protocols (cleaning, clearing trash, painting, and re-plastering), to reparative works (replacing broken shingles, sistering, straightening structures), to strategic interventions (co-living arrangements, shared amenities), to additions aimed at increasing social capital (community kitchens, daycare centers), to strengthening neighborhood networks (pooling capital, sharing facilities), the design of an entire repair strategy at every scale advocates for a value shift, one that privileges care labor above newness. Primarily undertaken by gendered and ostracized populations, upkeep work is considered belittling to many. Shah’s project challenges this perception through a socio-spatial tandem design by illuminating the crucial relevance of repair work both for buildings and communities—in a context where new construction is halted.

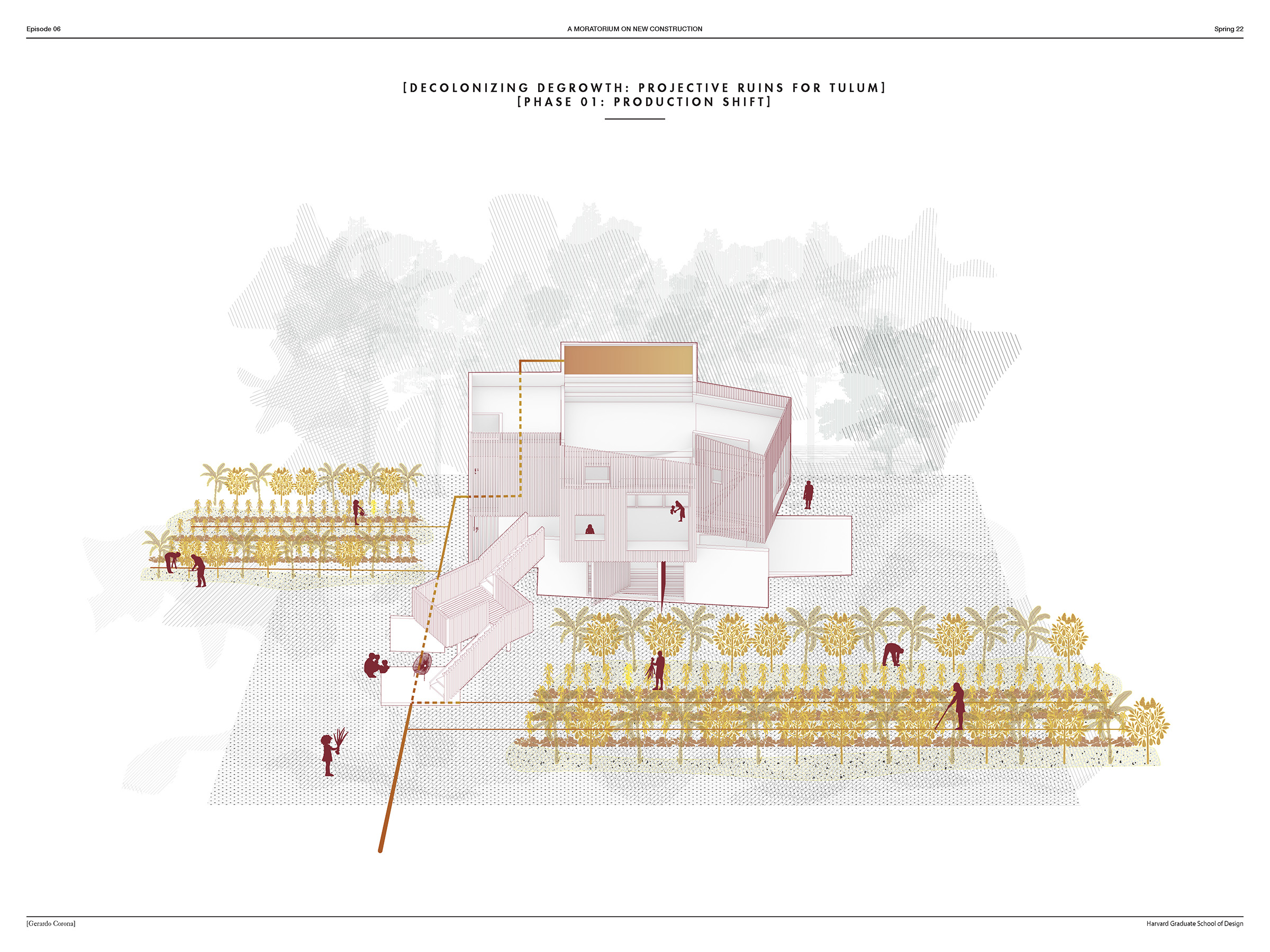

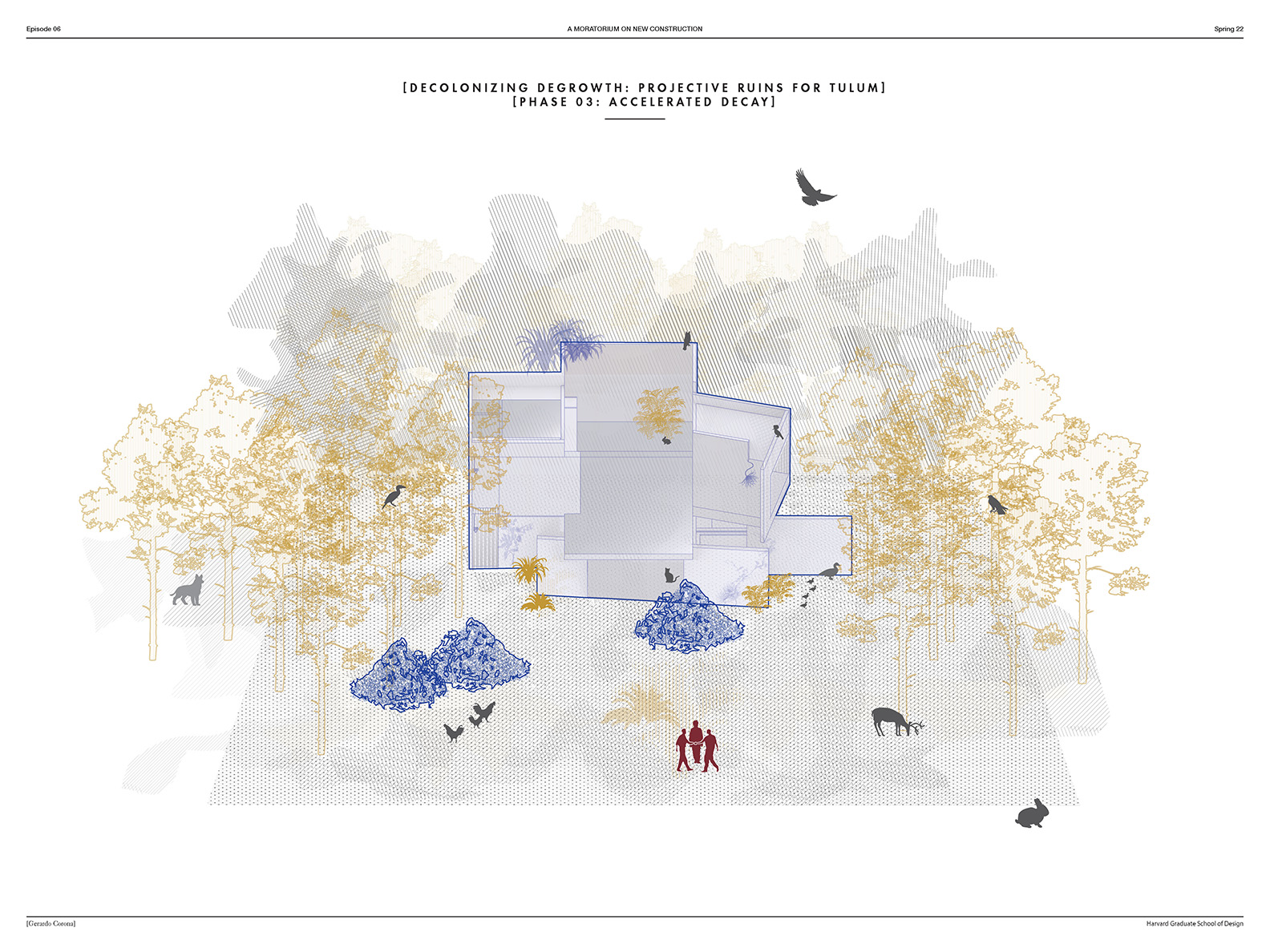

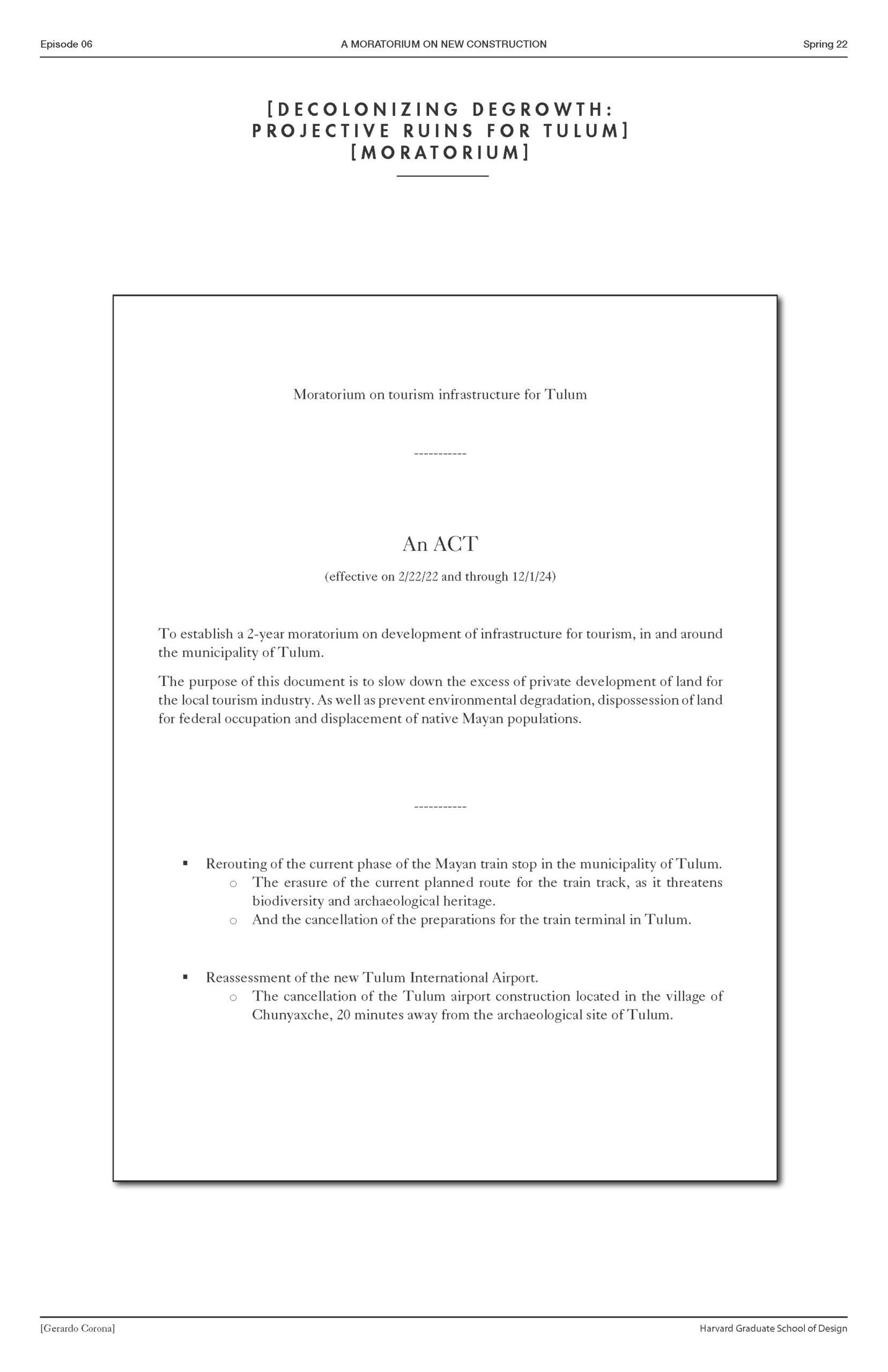

On the shores of the Yucatán Peninsula, Tulum is the latest Instagrammable ecotourism destination, with its pristine beaches overlooking the Caribbean Sea, which already is dotted with so-called eco-resorts and sustainable Airbnbs. Tourism growth is highly contested by local communities who oppose the construction of a high-speed Mayan Train aimed at ushering in more visitors. Indigenous voices have pointed to the harm caused to the area’s fragile ecosystem by constant growth within their economies. Turning these calls into a radical design brief, Gerardo Corona Guerrero (MAUD ’23) designs the gradual recess of tourism activity in Tulum.

The project disputes the success story of ecotourism and imposes as a first step a moratorium on tourism-oriented infrastructure. Considering that the “reconstruction of nature” is an equivocal concept bordering on eco-fascism, the project embarks instead on an incremental approach, phasing measures across a time span of 70 years, from reparative ecologies to deconstruction and material reuse. It articulates a decolonial understanding of degrowth toward a negotiated human stewardship of the land.

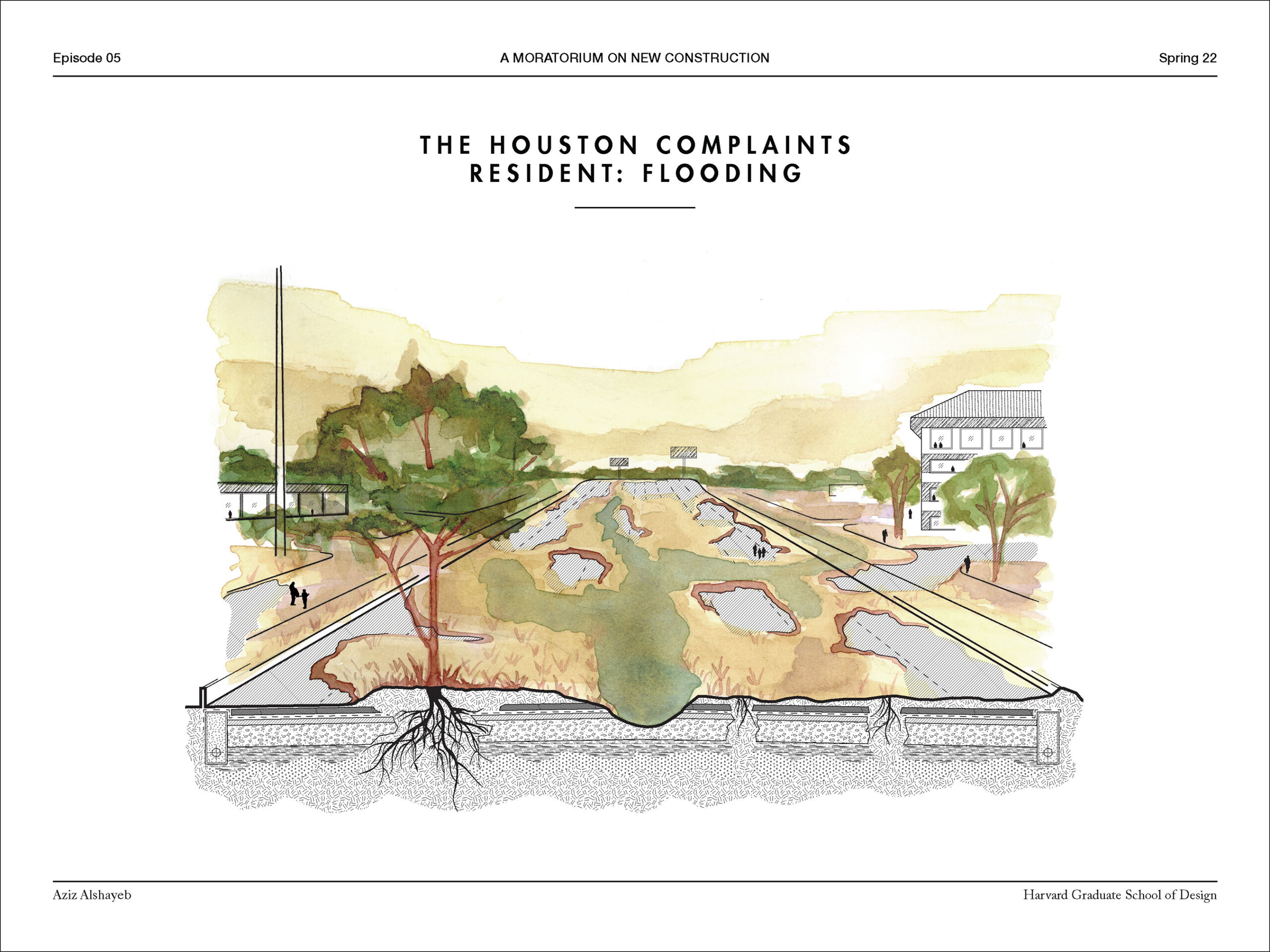

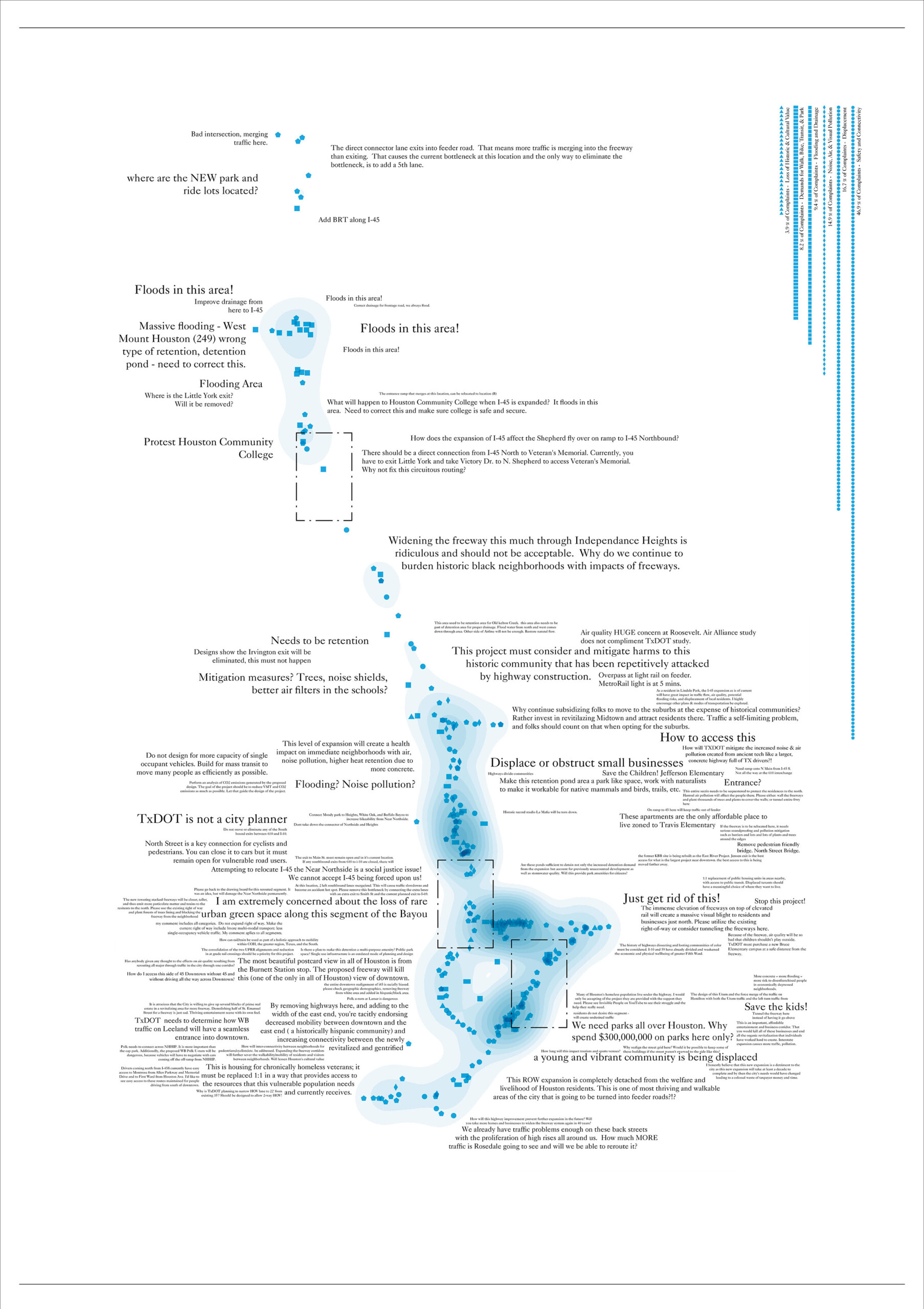

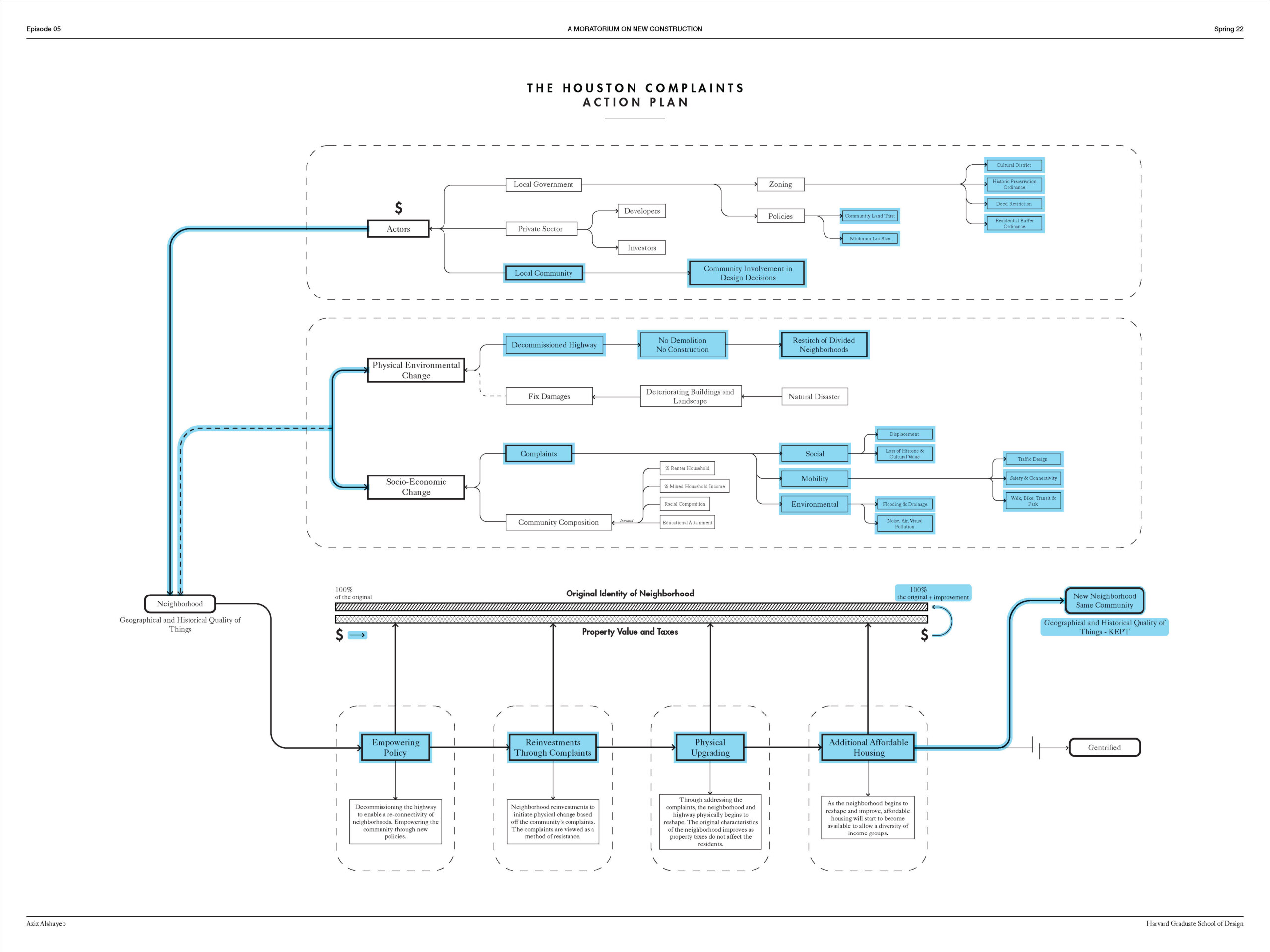

Going against the grain, Aziz Alshayeb (MAUD ’23) proposes a critique of the current trend of demolishing highways. He exposes a national agenda of hardcore gentrification and CO2-heavy development operating under the auspices of post-oil mobility and community betterment. In this context, the project proposes a moratorium on the demolition of Highway I-45 in Houston and puts forward a counternarrative to highway demolition that is based on Sara Ahmed’s concept of “complaint as resistance.”15

Taking community grievance as mandate, the project seeks to listen to all—from anyone who has registered a complaint, and from children to bees—to articulate an alternative program to the kind of solutionism that currently plagues design. With tools including legal frameworks and ecological measures, the project pushes against the evils of urbanization, including environmental degradation and gentrification and their manifold consequences. What emerges is a future of peaceful cohabitation between nonhumans, humans, and our obsolete infrastructures.

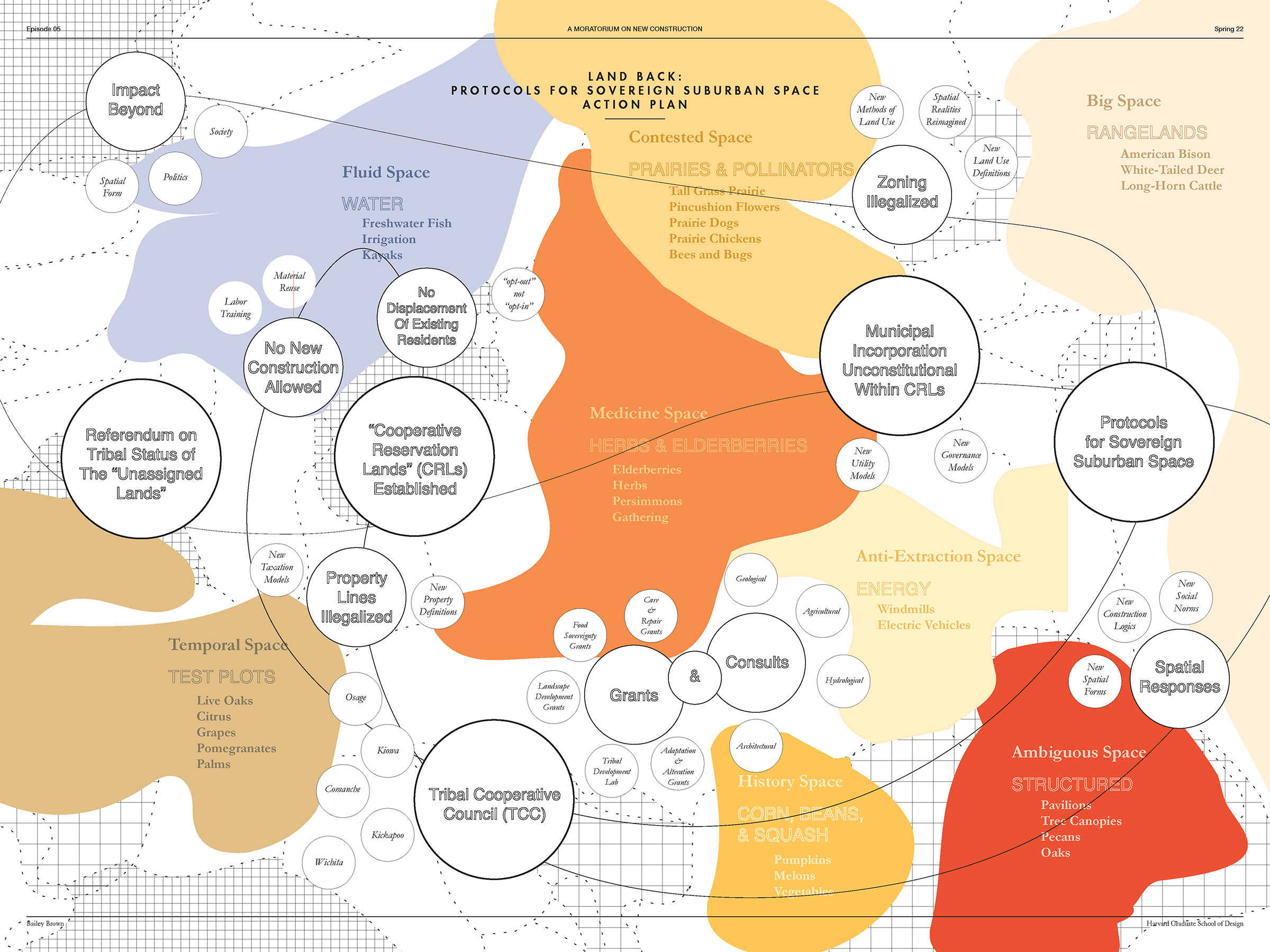

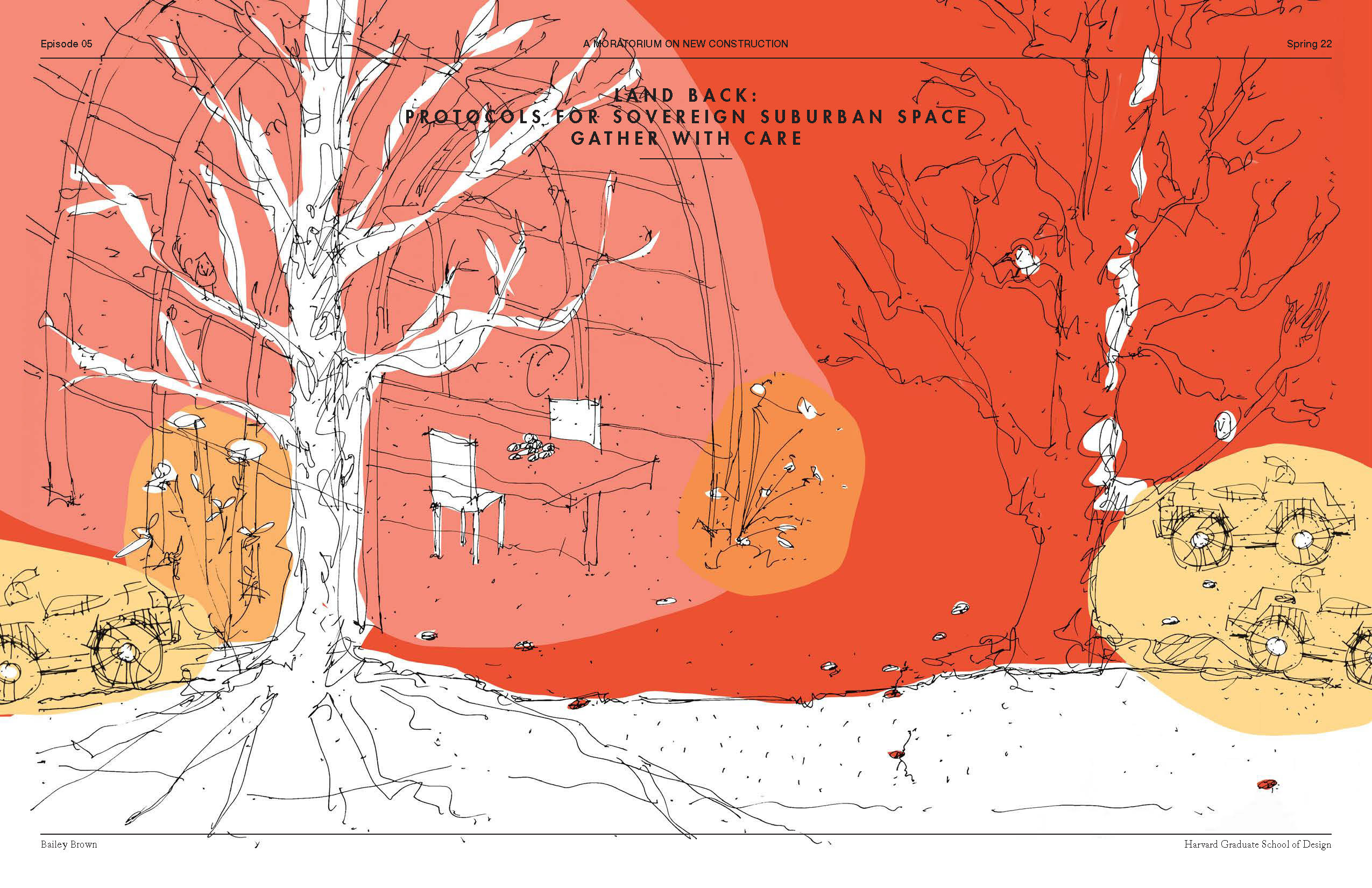

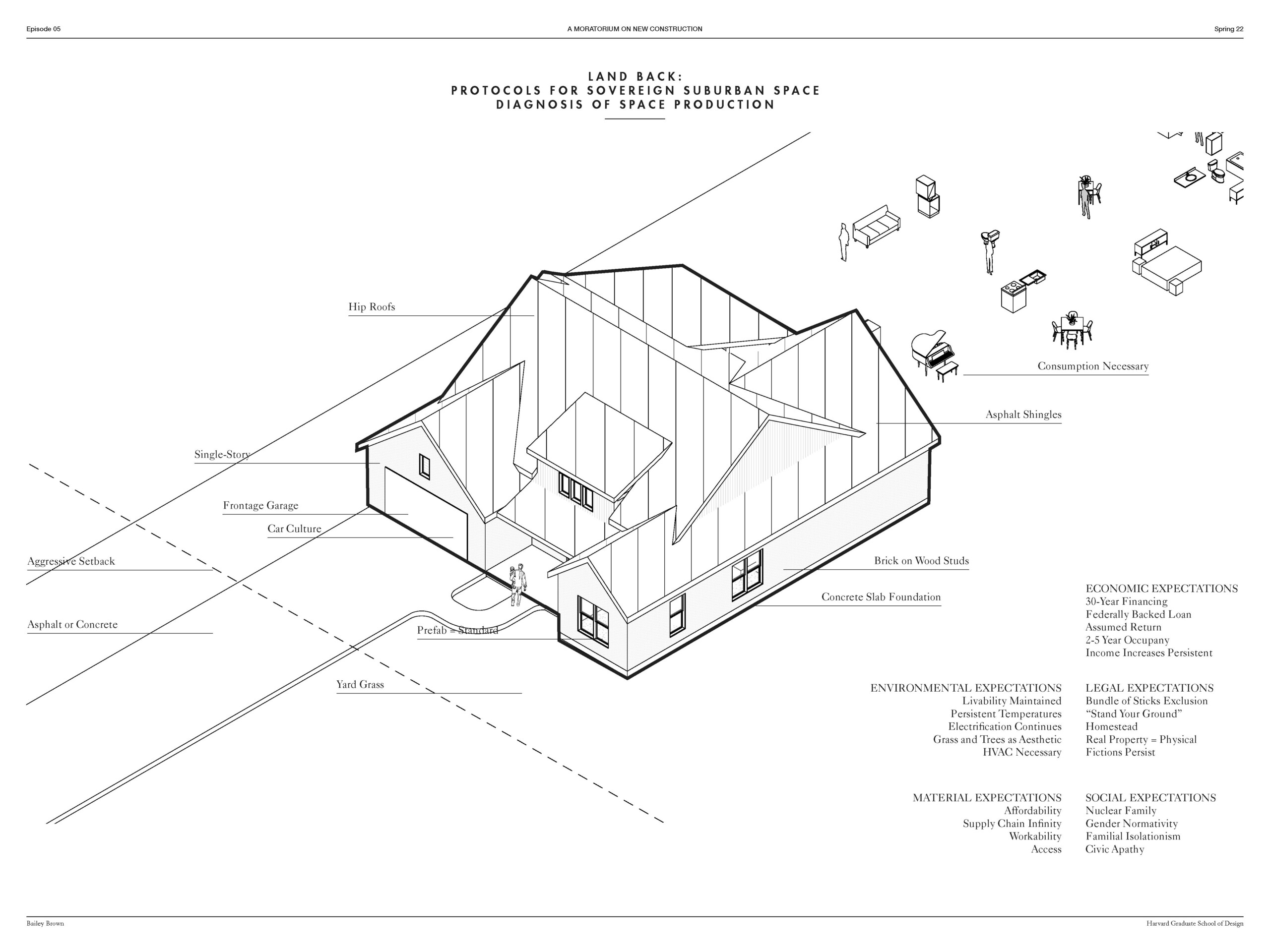

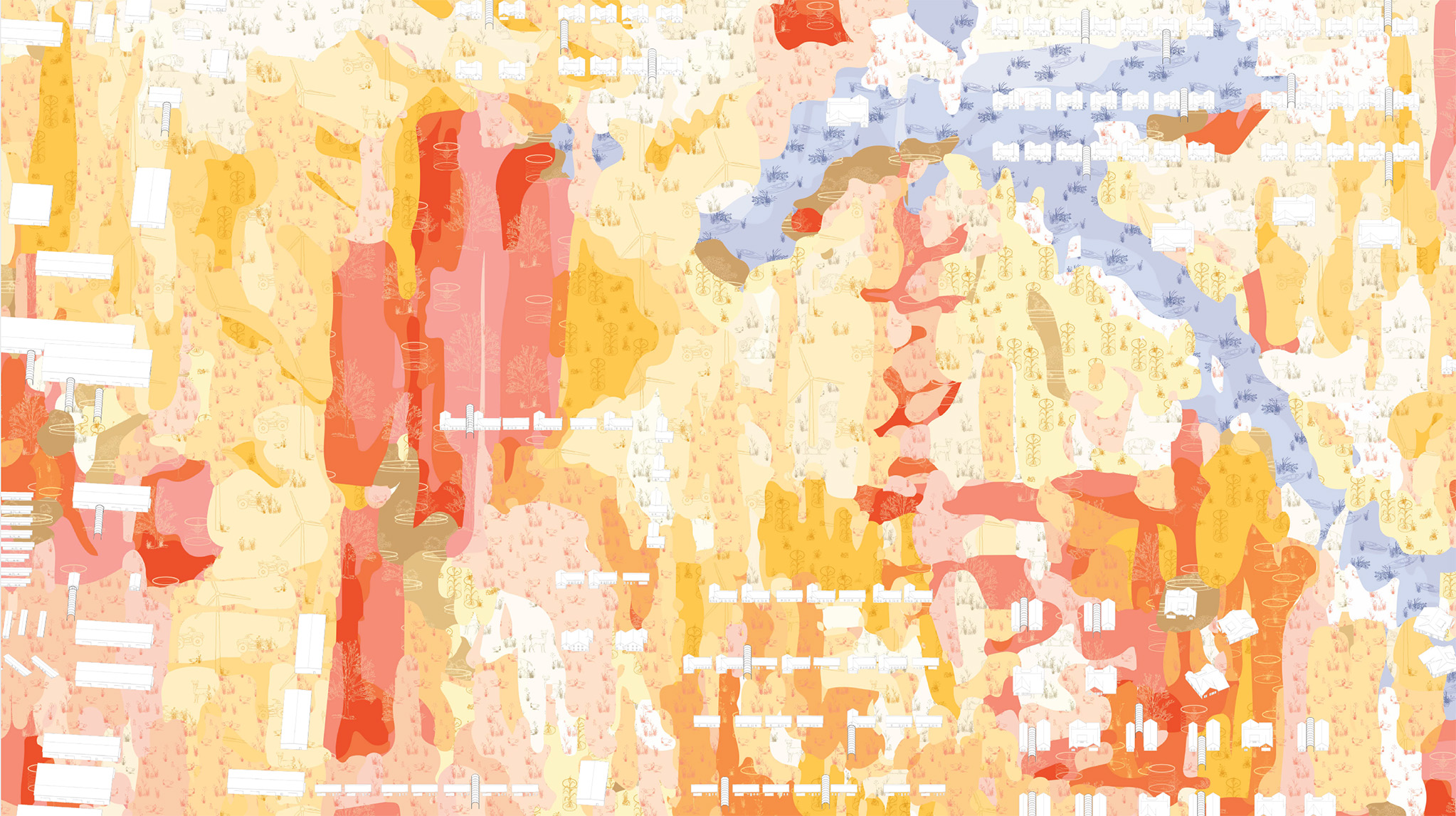

Starting from the perspective that the single-family home is an unsustainable, energy-intensive housing type that is itself fundamentally grounded in colonization, Bailey Morgan Brown (MArch ’22, MDes ’22), a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, proposes a moratorium on suburban sprawl for Edmond, Oklahoma, a site she describes as being paradigmatic of settler-colonialism. She argues that the single-family house exemplifies the combined burden of legal, economic, environmental, social, and environmental pressures, in the form of mortgage financing, lawn care, air conditioning, car infrastructure, normativity, materialism, and low occupancy rates, among others.

Going further, Brown develops a protocol for establishing a sovereign suburban space, articulating a plan for how “land back” would actually play out. Her plan unfolds into a multilayered strategy that includes a land transfer of “unassigned lands” to a Tribal Cooperative Council; a mandate against the displacement of existing residents; the termination of property lines and of zoning and the creation of new land use definitions; and the development of ambiguous, contested, fluid, and temporal spaces for energy production, medicinal vegetation, nonhumans, crop production, and new models for taxation.

These few examples speak of the incredible potential of what design can do if new construction is not an option—the potential to confront the built environment’s past, present, and future and to engage with existing building stock to question the current economic model of development and to move forward toward a better industry. Pausing construction problematizes the narrative of progress and techno-positivism that propel capitalist societies as well as the mandates for their design. Buttressed by an imperative for boundless economic growth proffered by postcolonial powers, those mandates sell “a better life for all humanity—a mentality that continues to structure global asymmetries,” as articulated by Anna Tsing.16

Nubian architect and decolonial scholar Menna Agha frames the call to “stop building to start constructing” as a prerequisite to setting off the reconstruction and rehabilitation of the built environments of the racialized, gendered populations bearing the brunt of ecological and social devastation.17 A pause would also allow the design professions to pivot toward resource stewardship, to remodel what we do and deploy design’s organizational capacity to (begin to) think about new forms of emancipated practice, to engage in remedial work, and to establish the care of the living as our sole priority.18 Somewhere between a thought-experiment and a call for action, a moratorium on new construction is a leap of faith to envision a less extractive future, made of what we have. It’s about building less, building with what exists, and caring for it.

Charlotte Malterre-Barthes is an architect, urban designer, and Assistant Professor of Architectural and Urban Design at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL). Most recently, she was Assistant Professor of Urban Design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where she taught studios and seminars and, in 2021, launched the initiative A Global Moratorium on New Construction, which interrogates current protocols of development and urges deep reform of the planning disciplines to address earth’s climate and social emergencies.

1 Achille Mbembe and Carolyn Shread, “The Universal Right to Breathe,” Critical Inquiry 47, no. S2 (Winter 2021): S58-S62, https://doi.org/10.1086/711437.

2 See David Harvey, Explanation in Geography (Jaipur, India: Rawat Publications, 2015).

3 See Martin Arboleda, Planetary Mine: Territories of Extraction under Late Capitalism (Brooklyn: Verso Books, 2020).

4 “A Global Moratorium on New Construction” was an initiative started in April 2021 and undertaken with B+, in the form of four roundtables that generated a wealth of ideas instrumental to articulate this work. I would like to thank for their generous inputs: Cynthia Deng & Elif Erez, Noboru Kawagishi, Omar Nagati & Beth Stryker, Sarah Nichols, and Ilze Wolff (1st roundtable, April 2021); Menna Agha, Sarah Barth, Leon Beck, Silvia Gioberti, and Kerstin Müller (2nd roundtable, June 2021); Connor Cook, Rhiarna Dhaliwal, Elisa Giuliano, Luke Jones, Artem Nikitin, Davide Tagliabue, and Sofia Pia Belenky, (Residents of V—A—C Zattere with Space Caviar (3rd roundtable, July 2021); Manuel Ehlers, Saskia Hebert, Tobias Hönig & Andrijana Ivanda, Sabine Oberhuber, Deane Simpson, and Ramona Pop (4th roundtable, August 2021); as well as Arno Brandlhuber, Olaf Grawert, Angelika Hinterbrandner, Roberta Jurčić, Gregor Zorzi, and Rahul Mehrotra for supporting this experiment.

5 Unites States Census Bureau, “Highlights of Annual 2020 Characteristics of New Housing,” Census.org (2020), https://www.census.gov/construction/chars/highlights.html.

6 Marcia L. Fudge, “Building the World We Want to See: What Do We Want Our Legacy to Be?,” in John T. Dunlop Lecture (Harvard University Graduate School of Design: 2022).

7 Thanks to Sarah Nichols for articulating this idea in the frame of the first roundtable, “Stop Building?” in April 2021 at the Harvard GSD.

8 Peter Marcuse, “Sustainability Is Not Enough,” Environment and Urbanization 10, no. 2 (October 1998).

9 Mbembe and Shread, “The Universal Right to Breathe.”

10 Yahia Shawkat and Mennatullah Hendawy, “Myths and Facts of Urban Planning in Egypt,” The Built Environment Observatory (2016). Omar Nagati and Beth Stryker in Stop Building? A Global Moratorium on New Construction, eds. Charlotte Malterre-Barthes and B+ (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Graduate School of Design, 2021).

11 See Andreas Neef, Tourism, Land Grabs and Displacement: The Darker Side of the Feel-Good Industry (London: Routledge, 2021).

12 Ilze Wolff in Stop Building? A Global Moratorium on New Construction, eds. Charlotte Malterre-Barthes and B+ (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Graduate School of Design, 2021).

13 See Matthew Desmond, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (New York: Crown/Archetype, 2016).

14 Marcuse, “Sustainability Is Not Enough.”

15 See Sara Ahmed, Complaint! (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021).

16 Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015), 23.

17 Menna Agha in Pivoting Practices. A Global Moratorium on New Construction, eds. Charlotte Malterre-Barthes and Roberta Jurčić (Zurich: Swiss Institute of Technology, 2021).

18 Elif Erez and Cynthia Deng, “Care Agency: A 10-Year Choreography of Architectural Repair” (Harvard Graduate School of Design, 2021).