In 2020, Cahiers d’art published Frank Gehry: Catalogue Raisonné of the Drawings Vol I, 1954–1978, the first in a planned eight-volume series devoted to the Los Angeles–based architect. Gehry studied city planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and received an honorary doctorate from the school in 2000 and the Harvard Arts Medal in 2016. The monumental project of cataloging Gehry’s drawings was overseen by the preeminent scholar Jean-Louis Cohen, who served as the Sheldon H. Solow Professor in the History of Architecture at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. A frequent guest at the GSD, a cherished mentor for students in the design fields, and an incomparable historian, Cohen passed away in August 2023. Upon the publication of the first volume of the Gehry catalogue raisonné, Cohen spoke at the GSD with Antoine Picon, G. Ware Travelstead Professor of the History of Architecture and Technology and Director of Doctoral Programs. Cohen’s remarks, edited for length and clarity, are presented here.

Why Gehry?

Why spend an enormous amount of my time working in detail on the work of Frank Gehry? I will simply say that Gehry is unquestionably one of the few architects who have completely revolutionized the discipline of architecture in the past 40 years. I will give two obvious examples: his own house in Santa Monica, of 1978, completely challenged the very core of domestic architecture. It introduced a totally shocking aesthetic register in what was then considered a materially conservative realm. Then, of course, the Bilbao Guggenheim: a building that completely changed the perception of a city. At the same time, it provided a different way of looking at the museum itself, with the design and construction both innovating in many ways. Gehry has left game-changing buildings, both small and big, throughout his career, including his latest projects.

Frank Gehry was also an old acquaintance of mine. For many years in the ’70s, as a student and young teacher, I couldn’t come to this blessed country because of my political affiliation. I was a Red, and Reds were not given serious visas. Suddenly, with the election of Mitterrand, this rule was lifted, and I made my first trip to the US. I met Peter Eisenman in New York. As I was going on to Los Angeles, he advised me to visit with a guy who was doing strange things in his backyard. This was July 1981, and Gehry and I became friends and have remained friends.

Why this book project? This brings us to a Parisian scene of the 1920s, the creation of a journal called Cahiers d’art by Christian Zervos, who was a Greek-born critic and historian with some independent wealth. He was behind the famous 4th Congress of International Architecture and its travel from Marseilles to Athens in 1943. Zervos created a journal in which art, architecture, ethnography, cinema, and music were discussed, with great people writing on architecture. More importantly, he produced between the ’30s and the ’60s, a 46-volume catalogue raisonné of Picasso’s paintings.

Cahiers d’art was resurrected around 2010 by Staffan Ahrenberg, a Swedish-Swiss art dealer and philanthropist. He developed other projects while republishing the journal, including a catalogue raisonné of Ellsworth Kelly’s paintings, curated and written by Yve-Alain Bois. (As you see, it’s a sort of French story all around.)

In architecture, the idea of doing traditional oeuvre complete is less common than in the visual arts. The concept of a catalogue raisonné based on architect’s drawings arose. It would catalog projects by drawings, and, preferably, hand drawings–not the drawings of the computers in an office—and in particular the study sketches.

There were only two obvious candidates, Álvaro Siza and Gehry. We decided to work with Gehry, and what followed was a very complex story. The number of volumes was set at eight from the beginning, and since we began Gehry has made many more projects. To give you a figure, Frank Lloyd Wright built 400 projects. Le Corbusier built 75, if you count Pessac, with its 150 dwelling units, as one. Gehry has built probably 170 out of 400-plus he has designed. (No one beats the world record of Albert Kahn in Detroit, who built 2,000 structures in the mid-twentieth century.)

Gehry was extremely generous in opening his drawers, at first in his office and in his huge Los Angeles warehouse. Then, a few years ago, the Getty Research Institute bought the first part of Gehry’s production: as he says, from his bar mitzvah to the competition for the Walt Disney Concert Hall in 1987. So, 30 years of work, mostly Los Angeles–related. These materials were later photographed by the Getty when the archives moved up to their Brentwood hill.

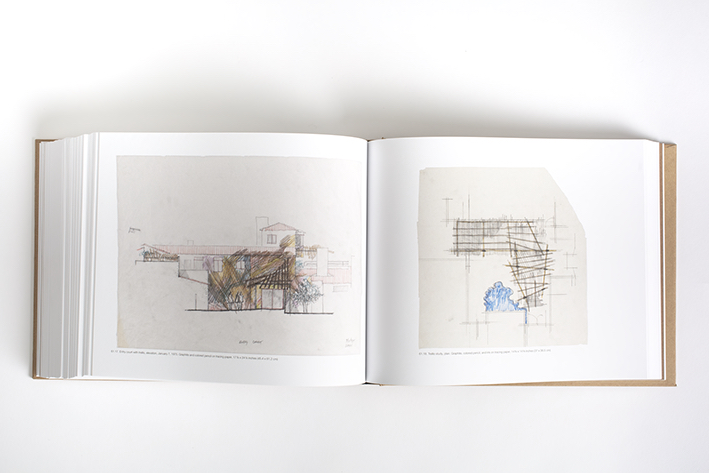

I had at my disposal masses of boxes and masses of rolls from the age of paper architecture, of analog architecture. It was a process of opening of the tubes, finding the sketches, and trying to tell a story. Gerhy did not obsessively date drawings day-by-day, so there is some guesswork. I had to enter into the logic of the project by trying to cross-reference drawings with related correspondence and reports to understand how a project came about, what the turning points were, and what were the moments when a project changed.

The first volume is a massive book, 550 pages, printed on very thick paper. It centers on 75 projects, starting with Gehry’s diploma thesis at the University of Southern California in ’54. I tried to document the process for each of them as well as I can. Gehry’s house is the lead project at the end of the first volume. I have also written an introduction on how Frank became “Gehry.” The text is not a mini-biography, but it still takes into account the various features of his training at USC in close contact with landscape designers such as Garrett Eckbo, as well as his later experience with Victor Gruen Associates, working on shopping malls and commercial projects, which had a major impact on his early practice.

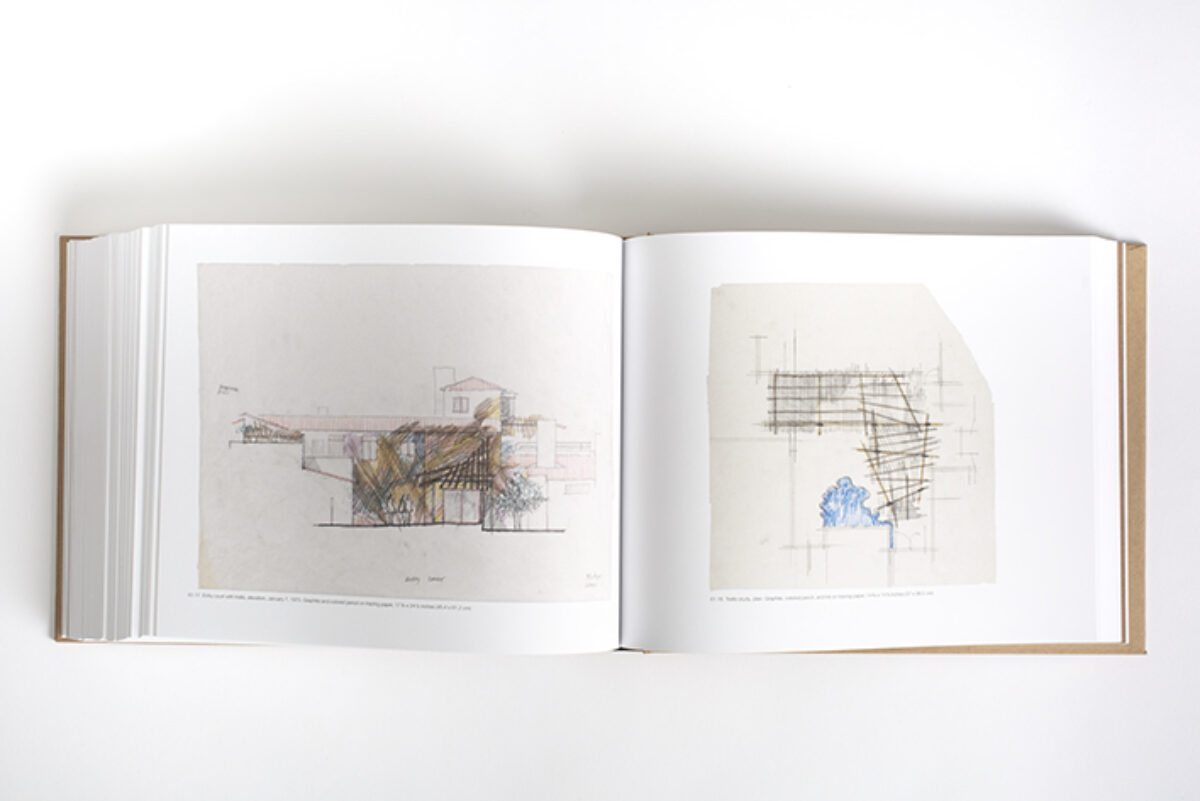

© Frank O. Gehry. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2017.M.66).

The book goes through all the early works, which are relatively unknown, from this first apartment house in Santa Monica, which is documented by relatively small number of sketches, to the more interesting commercial projects. One of my hypotheses is to insist on the sensuality of the commercial projects, in which we find the hand of Frank and the hand of Gregory Walsh, his partner of the time. Walsh had studied with Gehry at USC, and they had trained each other to draw in exactly the same manner in order to fool their instructors and to be able to replace each other for juries. It’s extremely difficult to differentiate the drawings because all the usual tricks for assigning authorship—how trees are made, how figures are made, how the lettering is done—don’t work.

Many drawings in the catalogue, candidly said, are drawings Greg made in the dynamic process of design work. When I had a doubt about a drawing, both guys—Gehry is 93 now; Greg is more or less the same—were unable to decide. “Oh, this must be by you, Frank.” “No, you’re kidding. It’s by Greg.” Then going to Greg, “Oh Come on. This can only be by Frank.” I was sometimes in trouble until the moment when Frank started self-consciously to work on smaller size sheets and really found a language that was only his own.

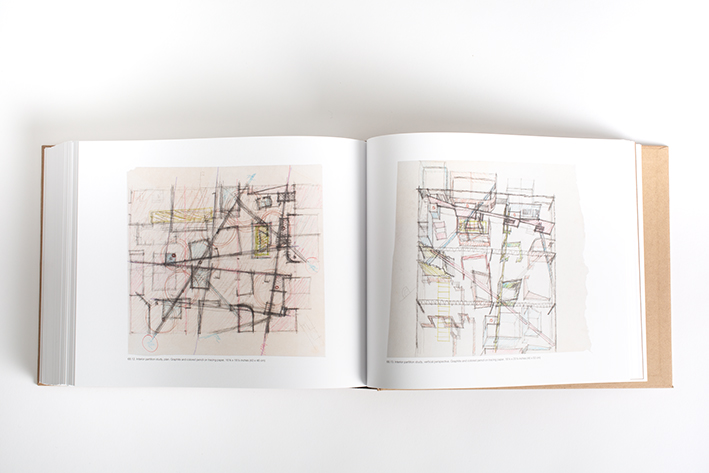

© Frank O. Gehry. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2017.M.66).

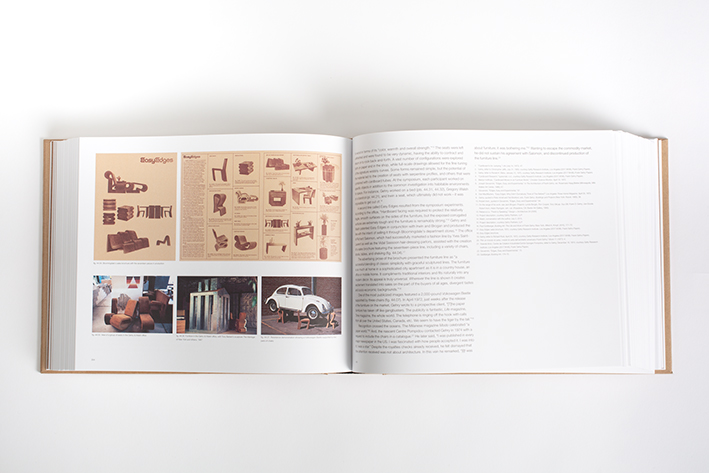

One of the interesting commercial projects is a department store for Magnin done in a series of iterations, the main one being in Costa Mesa in Orange County. Gehry worked at eliminating what he called “the clutter around the goods.” There is a very interesting reflection about the ordering of commercial space, the handling of light, the handling of sound, all of which comes from his training with Victor Gruen. Gehry had the ability to coalesce lots of consultants and work with them over a long time, and this is something that comes from the matrix of Gruen’s design work. He developed an integrative device called a “tree” in the Magnin store. He organized hangers, hanging clothes or shoes, lettering, and direct and indirect lighting all together, to avoid the dissemination of these elements around the space. The handling of the commercial space was, for Gehry, excellent training for the design of museums at a later stage. Dresses were replaced by sculptures, but the same preoccupation at cleansing the space in the museums is evident.

There are moments in this volume we see a sort of anxious quest for an identity, for language. When we look at the projects themselves, we see a series of echoes of other architects. We have Schindler. There is a lot of Wright, even some Le Corbusier. In one project designed for a woman sculptor in Brentwood, it’s clear that Gehry had been impressed by Le Corbusier’s church in Ronchamp, which he had visited during his long stay in France around 1960 or 1961. We see Gehry trying to observe Japanese architecture, but this was mostly the work of Walsh observing Frank Lloyd Wright. He knew everything about Wright, even if he disliked him as a person and was totally hostile to his political positions.

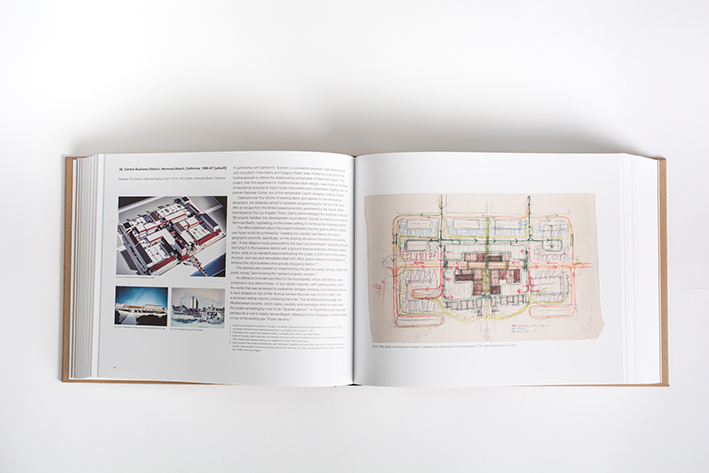

© Frank O. Gehry. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2017.M.66).

The Danziger House, which is very interesting project of ’65, is the first project of Gehry’s that I ever saw, as it was for many others in my generation, precisely because it was published on a page of Banham’s Los Angeles: The Architecture Four Ecologies in ’71 with an analysis connecting Gehry to Schindler. Banham says that Gehry was the first architect in Los Angeles to return to and to engage with Schindler’s preoccupation with geometry. But one could also see an echo of [Irving J.] Gill’s scheme in Santa Monica here.

Gehry tells interesting stories about Schindler, whom he had known and with whom he had a real friendship. Throughout the book, one sees how Gehry begins to appropriate what observers, beginning with Banham, have called the “dumb boxes” of Los Angeles: the nearly windowless boxes that line up the boulevards of the city. This is his first, I would say, relatively cubistic project: the Faith Plating Company, which he built even before the Danziger Studio.

Gehry developed contacts with Los Angeles artists. They were friends. He knew their work. They sometimes became patrons, as in the case of Ron Davis. They became role models in his attitude as an architect, and they sometimes provided him more concretely with aesthetic devices and aesthetic patterns, which he would integrate in his work. This is evident in the unbuilt version of a Santa Monica mall: Gehry’s last big commercial project. I can’t help but parallel with Johann Geist’s legendary book of Passagen [Ein Bautyp Des 19. Jahrhunderts], which was being translated into English at that time. If we look at the famous sign of the same Santa Monica mall supergraphic, it’s tempting to imagine a parallel with Ruscha, whose lithograph Gehry had on top of his fireplace, and still has it there.

There were failures also, and I’m mentioning them. Sylvia Lavin has written somewhere briefly about the failure of Gehry to build the house for Ruscha, who was arguably the Los Angeles artist who could be considered as closest to him.

We can also see Gehry building a persona and a discourse based on the rejection of rules, the breaking of rules. He was extremely skeptical about the discourse of architectural aesthetics. Le Corbusier published more than 45 books. Mies wrote maybe 40 articles. Gehry wrote probably three or four articles. He wrote fantastic letters where you find extremely precious lines. The one I prefer is in a letter to a PR person in Los Angeles, a parody of Mies van der Rohe. Gehry writes, writing with a German accent, “I don’t want to be good; I just want to be interesting,” echoing the famous and opposite statement of Mies. There is a corpus of Gehry’s declarations and hundreds of interviews, if there are few articles to speak of.

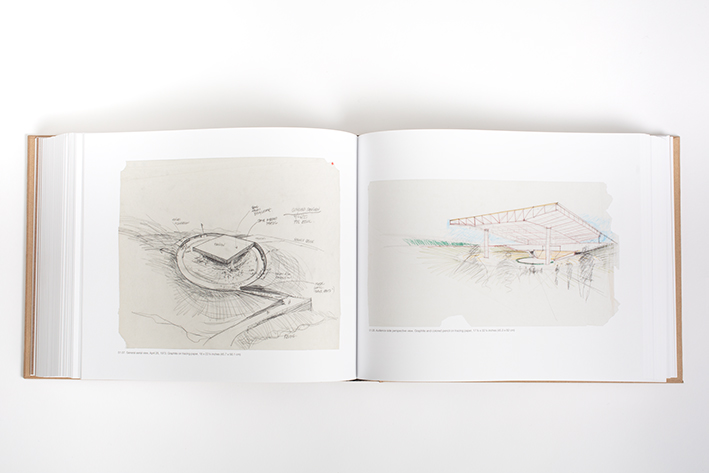

© Frank O. Gehry. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2017.M.66).

In one of those articles, for the National Architectural Press in ’76, Gehry says that he’s at a loss to differentiate between what is ugly and what is beautiful. He theorizes what he calls “cheapskate architecture,” saying that he’s working with materials which are in general, considered as discards. This is clearly something which echoes the work of Rauschenberg in painting.

The beginning of the discourse of fragmentation starts with the idea of breaking down the domestic project into specific spaces, with specific boxes corresponding to the various components of the residents. This unbuilt project, for a Santa Monica gallery owner, is a major one, as is the project for the Jung Institute, which shows autonomous volumes put over a mirror of water.

And of course, there are the drawings of the house in Santa Monica. I found a set of unpublished drawings. One is a very curious attempt I would interpret as using this fence around the initial bungalow, with vertical wood planks that seem to echo of Aalto’s project of the 1930s for Paris and the New York pavilions. Gehry is known for repeating to everyone that he had an early epiphany about architecture in Toronto while listening to an unknown, at least to him, Finnish architect who turned out to be Aalto.

There are many, many sketches of the house, which is a very complex demonstration of all his skills. It’s the project that concludes this first volume—and also the one that brought Gehry into the headlines. Allesandro Mendini’s Domus cover story discussing the project was probably the first really perceptive essay on Gehry.

Volume One is also the history of Gehry discovering, using, and manipulating, and in a way, challenging, teasing the typical frame of Los Angeles domestic architecture. And I will end on a hypothesis, which is probably one of the hidden ones, the many hidden ones in the book: I don’t think that Gehry would have emerged as he did with these first decades of design in a building culture based on steel, or, even less, concrete. A lot of his architecture, many of these architectural decisions and provocative proposals, were based on the freedom given to him by the wood frame. He is an architect of the two-by-four.