Pairs is a student-led journal of conversations that matches subjects with objects, interview with archive. The journal is organized around a diversity of threads and concerns relevant to our moment in the design disciplines, bringing forth candid exchanges and provisional ideas.

For this conversation, featured in Pairs 4, Isabel Lewis spoke with Theaster Gates, an interdisciplinary artist whose work focuses on social practice and installation art. Trained as a potter and an urban planner, Gates is the founder of the Rebuild Foundation, a nonprofit cultural organization that aims to uplift under-resourced neighborhoods. He is based in Chicago.

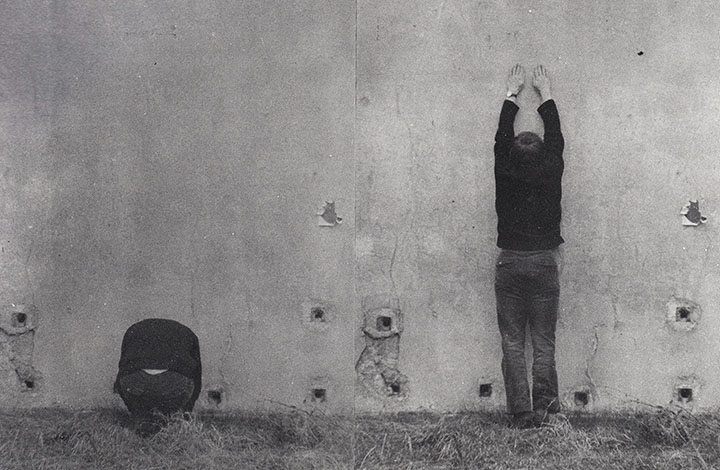

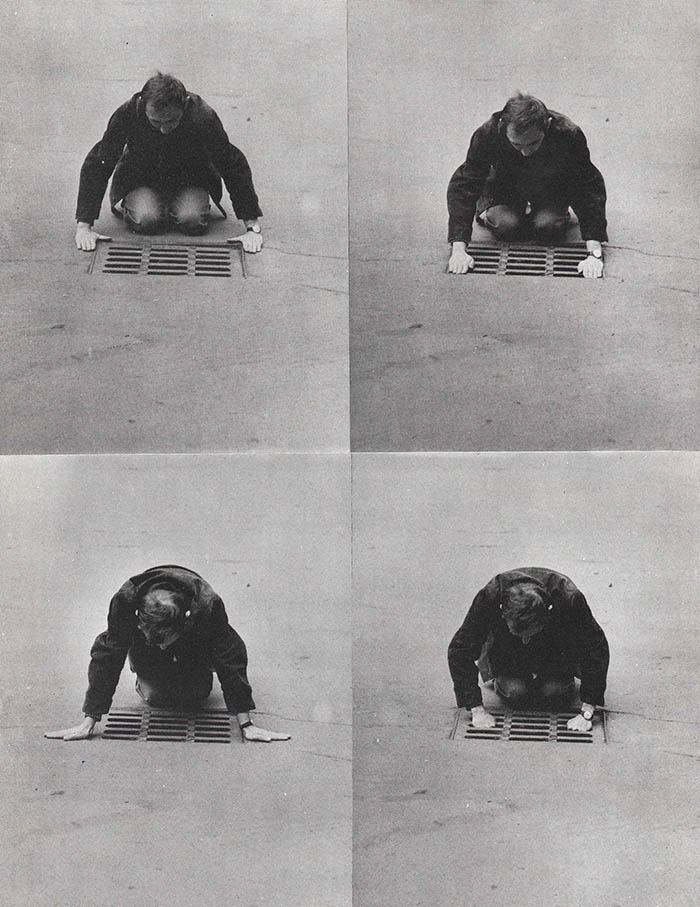

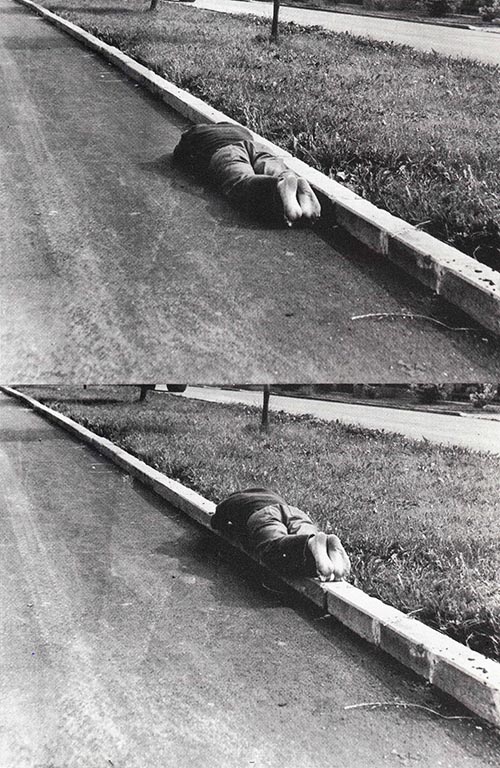

At the center of the conversation is Karel Miler’s Actions, a series of photographs of the artist in semantic translation. Made in Czechoslovakia in the early 1970s, these images were intended to be a form of visual poetry exploring corporality and spatial constriction. A Zen practitioner, Miler is concerned with representations of universal and individual forms.

Theaster Gates Let’s begin.

Isabel Lewis The first time I saw your work, I was nineteen and living in Portland, Oregon. I was taking a sculpture class, and the professor showed us a documentary about your practice. At the time, I was thinking about the way space is affected, how there’s always a social aspect to spatial construction. Your work helped me open the door to the field I’m in now, design and landscape architecture.

Recently, this came full circle, because I went to see the film Showing Up, which is about a young woman, a sculptor, who works at an art school in Portland, which I think is based on the Oregon College of Art and Craft.¹ It brought me back to this very specific time and place, this memory of living in that city and trying to figure out what sculpture meant to me. So it had a great impact on me when I saw in the end credits that you contributed art to the film. I was thinking we could start by talking about how memory informs your work.

TG This happens for me, too. Art and artists, they follow us through our lives. The more we learn about ourselves and the more experiences we have, sometimes a work of art shows up and carries a different meaning. It might mean more, it might mean less, but it continues to haunt us and be a part of us. For me, buildings, spaces, and materials also have that haunting effect. No matter what an object is, even the paint that you buy at a store, everything has history. It has an origin story. It has an eternity that precedes you. When you think about acrylic paint or oil paint, even if it’s new, it has a history: the tube that it’s in wasn’t made today. Those processes are in fact part of a found or reclaimed identity, even though it’s a new paint. You buy new wood at Home Depot, and it is not new wood. It’s sometimes preexisting wood that’s been planed again, it’s a tree that has a history, an origin story. For me, saying that a thing is new or has history, it’s everything. You can connect the fact that everything has a history and a narrative to, let’s say, a Buddhist or an Africanist religious belief around animism, or the idea that things have life inside of them. I think what I’m interested in is participating in the truth of the life that is within things.

The more I spend time with materials, the more I think, “Oh, yes, my dad was a roofer. Yes, roofing paper and the materials of roofing are important to me because of that history.” But I also think that those materials have a life of their own, and that if I spend time deeply thinking about that life, then great things could happen with those materials. The South Side of Chicago wasn’t born impoverished. The buildings that are currently abandoned, they weren’t always abandoned. Those buildings have life in them, and it feels like my job is to recognize, exhume, and celebrate the great lives of these spaces. The more I believe the life these buildings have lived was important, the more I want to preserve this, the more I feel like, “This thing deserves to live, deserves to continue to live.”

IL I love that idea of reembodying a place or an image. The striking thing about this set of photos is how physical they feel. I have this bodily response where I imagine myself in these positions and how these things feel. There’s a natural tendency to want to bring life into inanimate objects.

TG Absolutely.

IL It also reminds me of paint, oil paint in particular. We have these names like Siena or Umbrian brown, and those come from the land. That’s the color of dirt in Siena. These materials are defined by their most fundamental origins.

TG Yeah. For every color that’s a natural color, there’s a plant or a mineral or an insect or a bark or a root that’s being crushed and ground to produce the thing that then allows us to produce beauty. I think that those processes and those roots, they have their own beauty. Let’s pull up an image, Isabel.

IL I’m drawn to Limits, as with many of these images, because there’s so much movement that’s implied but not ever shown. You see the beginning and the end of an action, but everything in between is just inferred. I think it goes back to what we were saying about time and timelessness, too. We think of performance as a time-based art, but in its documentation, it becomes a moment completely out of time. When I look at this, I feel it in my body, and it becomes much more spatial than anything else, much more corporeal.

TG I also think that we’re not necessarily analyzing the photograph itself, but the choices behind it. In 1973, Ektachrome was already available.² We were already in good and saturated color, but to have this image in black and white adds to the austerity, meditation, simplicity, it makes those contrasts pop even more.

IL The artist, Karel Miler, was a Zen Buddhist. That stayed with him throughout his life, even after he stopped working as an artist. A lot of these images are meant to be a translation of poetry or meditation into a representative image. I wonder what you would end up with if you were to translate these images back into language.

TG Measurement is language in that you’re taking a somewhat arbitrary sense of space, and you’re codifying space with lines, and then you’re giving those lines a shared understanding, so that we all agree to what a foot is or what a meter is, what a yard is, we agree to what a millimeter is, and as a result of our shared vocabulary, we’re able to then translate information across time.

IL Does translation feel like an adequate way to describe how you move through different scales, from pottery to neighborhoods to larger urban structures?

TG I think about translation all the time, Isabel. I do. Sometimes when I’m making a work of art and I sit down with a journalist and they look at a tar painting, the first thing they say is, “So your dad was a roofer?” It’s like, “Well, yes,” but the thing that I’m trying to convey is not necessarily about my relationship with my father. There are other, more sophisticated codes embedded in these materials, not just one prescription.

Translation also has to do with our ability to deeply interpret the meaning of a word or moment. I think about translation in the sense that art is a stand-in for my words. It’s a set of codes that goes without the need for my body, and it’s able to say things, sometimes simple things, sometimes more complicated things. That’s cool.

I recently wrote an essay about a dear friend of mine named Tony Lewis, an artist who uses language in his drawings, and it led me to look up the history of shorthand.³ It seems like an abstraction, but people who understand it can translate shorthand into language. If people across languages learn the same shorthands, then you can sometimes know universal shorthand without having to know the language. All of these modes are modes of translation and interpretation. It requires that you have a base knowledge of something, and then you add to that base knowledge a symbol that is universalized. In that sense, Tony’s work reminds me of this international code. It reads as abstraction, but only because most people don’t read shorthand. I’m saying so much right now, Isabel, I’m so sorry.

IL No, no, it’s really wonderful.

TG If we go back for a second to measuring in this image, what I love about it is he’s trying not only to set up the limits of his body, like the length of his hand, but also to show the deep correlations between his body and a crevice, or a crevice and the rise of a stair. I think these things are so relevant for landscape architecture in that sense, because the rise seems incredibly human. When you think about stately stairs, the rise is often short, sometimes the run is super deep. You actually have to take two or three steps for each tread, and it’s interesting to think about how when it gets past the foot, when it gets to three feet or five feet, it reads as grand because it’s bigger than our body.

IL Form and the body have such an interesting relationship to scale. All those books of the architectural standards say that a countertop is going to be this high and a cabinet is going to be this high because a typical body looks like this, but then my mother can’t reach any glasses from the top shelf because she’s not a five-foot-nine male. It’s worth subverting those expectations to measure space by atypical metrics. I made a Klein diagram a little while ago about tables and chairs.⁴ A baby sitting in a highchair, that’s a chair and a table in one element, with a very prescribed use. But if you’re perched over the kitchen counter, eating takeout from a container, you’re not in a chair nor at a table, and you’re not using the counter as intended. It’s that individual expression, I think, that really makes a place belong to someone.

TG Well, last summer just before going to Japan, I went to a yoga class and the yoga instructor asked, “What do you want to get out of the class?” I said, “I need to be able to sit cross-legged for two to three hours.” What I needed most from yoga was to help me respect the social customs of the dinner table. I knew that moving from my cultural predisposition to a Japanese cultural predisposition would require work, exercise, stretching. I think that sometimes architecture and landscape architecture can inform our new cultural norms. It could allow us ways of getting out of ourselves and maybe new ways of thinking about what dinner could be.

IL The reason why I ended up including this one was because it made me reevaluate the simple idea of holding something in your hand, a perfect weight, a textural variation. By taking a record out of its sleeve or by thinking about how you’re going to shape a pot or play an instrument or cook a meal, all of these things are fundamentally about how we touch the world. It’s not something that’s exportable or translatable.

TG Touch is important because it is one of our first phenomena. Whether it’s the first touch when a baby is born, or consistent touch as a baby ages, or the ability to process information like hot and cold, it’s the way we learn to be in the world and encounter our limits. These images speak to my own interests in the ways they demonstrate how having a sense of how texture affects a viewer of art. People don’t want to just see things; they also want to touch them and know them. To see is to know, but to touch is to also know.

IL Yes, and with the Archive House and the Johnson Publishing Company artifacts, you could make the argument that these objects should be preserved in a museum. But there’s something about flipping through an object that’s very different.

TG Yes, and back to this conversation about the different ways that architectural archetypes show up, who’s to say that the Listening House isn’t a more perfect museum?⁵ Because we have the ability to touch things—turning the pages of a book, looking closely at a glass lantern slide—we can be more than just witnesses to them by being witnesses through them.

The truth is, when you advance in your research at universities like Yale and Harvard and the University of Chicago, you can gain access to special collections and touch things that other people can’t. I think that sometimes touch is also about who has access and who doesn’t.

IL Even with this magazine, it’s partly because we’re all at the Harvard Graduate School of Design that we are able to have access to these people and to these objects. It’s a privilege. I think the hope is that by doing and sharing this work, we’re making the process at least somewhat more accessible. But it is true that touch is something that you’re very lucky to access. I think there’s probably a lot of lack of touch in the world right now.

TG For me at least, as I was building the Listening House, Archive House, and Black Cinema House, and ultimately the Stony Island Arts Bank, I was definitely thinking about a person’s experience of these different spaces. The experience of that has everything to do with trying to create more access to the place, more access to people. I feel like we’ve at least been successful in helping people gain access. I’m quite proud of that.

IL I’ve been thinking a lot about the way that clay in particular holds memory. It holds fingerprints, and the act of throwing a pot is so intensely physical, really, really hard work. When you hold something in your hands like that and it’s shaped by your hands, it has your imprint on it. But it’s interesting to think about the way that that is scalable through other materials as well.

TG Absolutely. It’s reasonable that when we’re doing renovation projects, if we take out a stone, like a terra-cotta cornerstone, from a building, we can see the marks of the maker. But they might also put in some funny anecdote, or write their name or the date, because these are not actually anonymous objects. They’re anonymous to us because the histories of those materials haven’t always been carried forward. But in fact, from a pot to a large structure, objects often carry the remnants of people’s touch. If you look close enough at most buildings, you’ll see the traces of the people who made them.

IL This is relevant to something I was working on last semester about Julie Bargmann’s work in rehabilitating toxic landscapes. In a landscape project, there’s this dual action of not erasing history but honoring it while also acknowledging that land often has a complicated past. How do we preserve memory in built environments or urban landscapes in a way that feels authentic?

TG I think sometimes art and conceptual practices can help us on that journey. Sometimes, and I think this is what we’ll get to with these photographs, performance and conceptual ideas help us tackle these bigger questions by putting the body present in ways that implicate a site, make you feel more compassion toward the site because of the complexities of the things that happened there.

I remember when Cabrini-Green in Chicago was being torn down.⁶ There was concern that poor people were being displaced, largely poor Black people, because that land had become some of the most important land in the city for its adjacency to downtown. It’s like, “Well, Black people still deserve the right to live in a place that they’ve been living in for the last fifty years, sixty years, for which nobody gave a damn.” The site has changed over time, but the people haven’t. What do you do when time has shifted people’s stigma of a place?

People who lived in Cabrini Green deserve the right to continue to live there, even if the land is now worth a lot of money. When they were excavating, there was a lot of clay underground. I remember just trying to get access to that site and that clay, to use it as a stand-in for the people who once lived there.

IL I think there’s this notion that a landscape intervention won’t do harm. It’s complicated because there’s one lens that focuses more on the rights of the biome and another on the rights of people. Of course, they go hand in hand.

TG We look to landscape architecture as the solution to neutralizing space and time. It starts with large projects that are government or municipality projects, but then you have private developers and privately owned public spaces.⁷ In these moments, we need landscape to give us something that is not an office building, not a residential thing. But that safe passage route or that new bike lane or that grove of trees is sometimes still a disruptive act of transferring a community space from one of people in need to one of people that have a tremendous amount. I think protecting green and public spaces is important, and also not using green space or landscape as the thing that disintegrates a certain community continuity is important.

IL What I’m trying to get across is that people can think of landscape as very politically neutering. It’s like, of course, who wouldn’t want landscape beauty in their neighborhood? But I do think that there’s a tendency when any project is approached with this developer-down, top-down approach that erases the individual user. Maybe the only way to really approach this idea is from the inside out, moving from what you can shape with your hands to eventually what can shape you.

TG I think we’re saying the same thing, Isabel, that every urban tool can be a divisive, derisive device that separates and disconnects as much as it can be a tool that aggregates and reconnects. There is no neutral tool, including landscape architecture, and I think it’s really powerful that you’re able to see that. There will be moments where you’ll be on big projects, and it’ll be like, “Fuck!” When we build these new cities, we haven’t given any thought yet to where people are going to commune.They’re building apartment buildings and they’re building bus depots and transit things, but they haven’t thought about places of worship. They haven’t thought about the park where people might do yoga.

IL Yeah, at least in the US, I feel like it can be a very capitalistic way of thinking. We consider how people can get to work but not about where they can get together. How do you think the work you’ve done in creating cultural archives supports community?

TG Well, right now, I’m in the center of downtown Chicago. You get used to seeing the same shit in every city, you know what I mean? We could be in New York right now, we could be in LA, we could be in Paris, we could be in London. One thing that’s interesting about the Arts Bank is that it shows up as an unexpected and autonomous form.⁸ Its use is so different from the typical use that’s evident on our urban streets. What makes the city special to me is the fact that there are things autonomous to that city. It’s not enough just to have the archive, it needs to populate the block in the same way that any other storefront could.

I think the Dorchester Projects gave me an opportunity to install my own interpretation of the architectural image of a block.⁹ Inside that architectural image are a set of things that are totally specific to what I care about. I love looking at images. I love looking at images with others. I love making music with images behind me. I love learning about other people’s histories through objects. In that sense, the bank became a place of congregation and shared values. Then it leads you to realize, “Oh, I don’t even have to go to the bank to look at these kinds of images. My grandmama has images on her wall that I never pay attention to—who are those old people on my grandma’s wall?” Before you know it, you start to have a new appreciation, not only for other people but for your own freaking family.

IL I think one of the things that’s particularly beautiful about photography is the dissonance between the original event and the reception of its documentation. Sometimes the documentation can spark a reimagining of its own in which you start building a narrative around the things that came together.

TG Absolutely. Images test the limits of a person, but they’re also about the deep recording of a specific moment. When you’re making the image, you don’t necessarily know that it is going to be important, but we’re looking at curbs and streets that may not exist anymore, buildings for performances that don’t exist anymore. But an artist punctuated this site, and we have proof of its existence. With the artist, we have a way to remember a thing that occurred.

IL We take these things as ready-made. The photograph is there, the paint is there, the canvas is stretched, et cetera. But then, when you remove an action from its documentation, it’s something completely independent. I’m thinking back to something you said in a TED Talk, that when you started the Archive House in the Dorchester Projects, even just sweeping it became a performance.

TG There’s a tension and a relationship between the gesture that one performs and the document that captures that gesture, and then eventually, what that documentation means for the future. I sometimes want to be able to go back and show people a moment when all I could afford was eggs and mushrooms and potatoes from the local market. It was food you had to eat that day, it was almost on its way out. As a result, the cost per pound was so cheap that I could buy five pounds of mushrooms for $2.50 and I could make a big frittata. I wish I had evidenced those days more. I wish somebody had taken a picture of me making my frittata and slowly letting that pan get hot, because people assume I’ve always had a chef, or I’ve always had handlers or some shit. I’m like, “No, that’s actually the last five years that I’ve had help.” But those gestures, those moments really matter. Me, when I could drop it like it’s hot, I could dance. It’s difficult for my nephews to imagine me partying, because the gestures that I make today as an older adult, they’re so different from the gestures that I made when I was 25. All I can say to them is, your uncle was the life of the party, trust me.

Endnotes

- Showing Up, directed by Kelly Reichardt, with performances by Michelle Williams, Hong Chau, and Andre Benjamin (2023; New York, A24).

- Ektachrome was a high-quality color film first produced by Kodak in the 1940s.

- Tony Lewis is a Chicago-based artist whose practice concerns semiotics, abstraction, and site specificity. He has exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Cleveland; Museo Marino Marini, Florence, Italy; and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

- The Klein Diagram is a four-group graph describing how elements are related to each other and their opposing forms. It was famously used by Rosalind Krauss in her seminal 1979 essay “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” to describe the relation of sculpture and architecture.

- The Listening House is one of several abandoned properties on the South Side of Chicago whose use Gates reimagined. Today, it houses a record collection of over 8000 LPs with cultural significance to the Black community in Chicago.

- Cabrini-Green was a public housing development built by the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) following the Second World War. Due to neglect and a lack of financial support from the CHA, the development fell into disrepair and became a symbol of urban blight. Its demolition was completed in 2011.

- Privately owned public spaces (POPS) are plazas, atria, or similar areas, typically in urban centers, that are open to the public while being owned and maintained by private corporations, often as a way to circumvent zoning restrictions or floor–area ratio regulations.

- The Stony Island Bank was vacant from the 1980s until 2015, when it was reopened by the Rebuild Foundation, a nonprofit founded and led by Gates to rehabilitate abandoned spaces on the South Side of Chicago. Today, the Bank serves as a local hub for artistic innovation and archival research, housing collections of music, film, magazines, and other significant cultural artifacts.

- The Dorchester Projects is a foundational expression of Gates’s interdisciplinary practice, in which urban design, archival preservation, and neighborhood engagement come together. In 2009, Gates purchased and then rehabilitated a set of neglected houses on Chicago’s South Side into vibrant cultural spaces, including the Archive House, the Listening House, and the Black Cinema House. In addition to serving the local community, these spaces are a model of positive urban restoration and collective action.