In 2022 and 2023, Monterrey, Mexico’s second largest city, experienced a critical shortage of water and, like Cape Town in 2018, was close to a Day Zero of water provision. The emergency made international headlines, as the state government rationed water for many of the city’s five million residents. While struggling at times to supply water to residents, Monterrey is also well-known for its severe floods that have peaked in intensity during deadly hurricanes, such as Gilbert in 1988 and Alex in 2010. In recent years the fluctuation between these extreme events has been intensified by a changing climate.

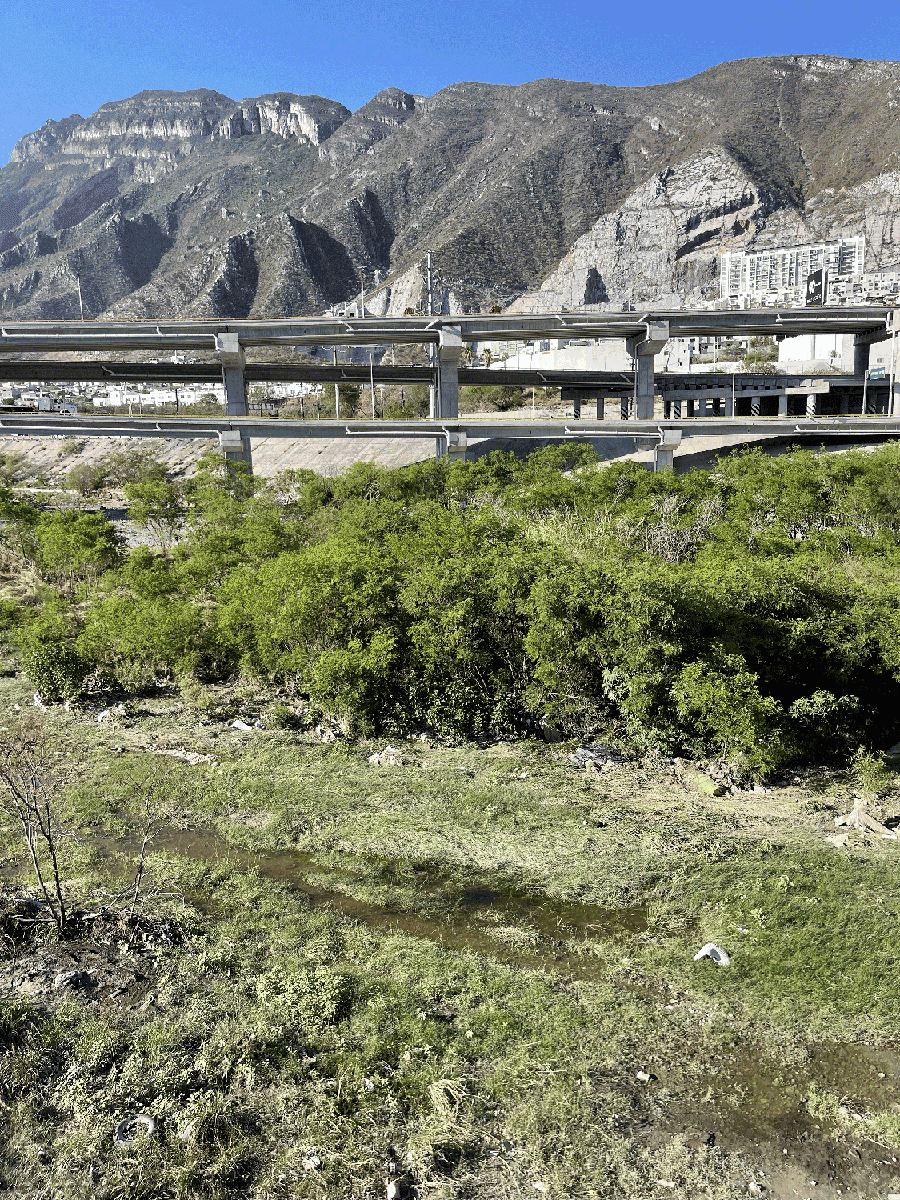

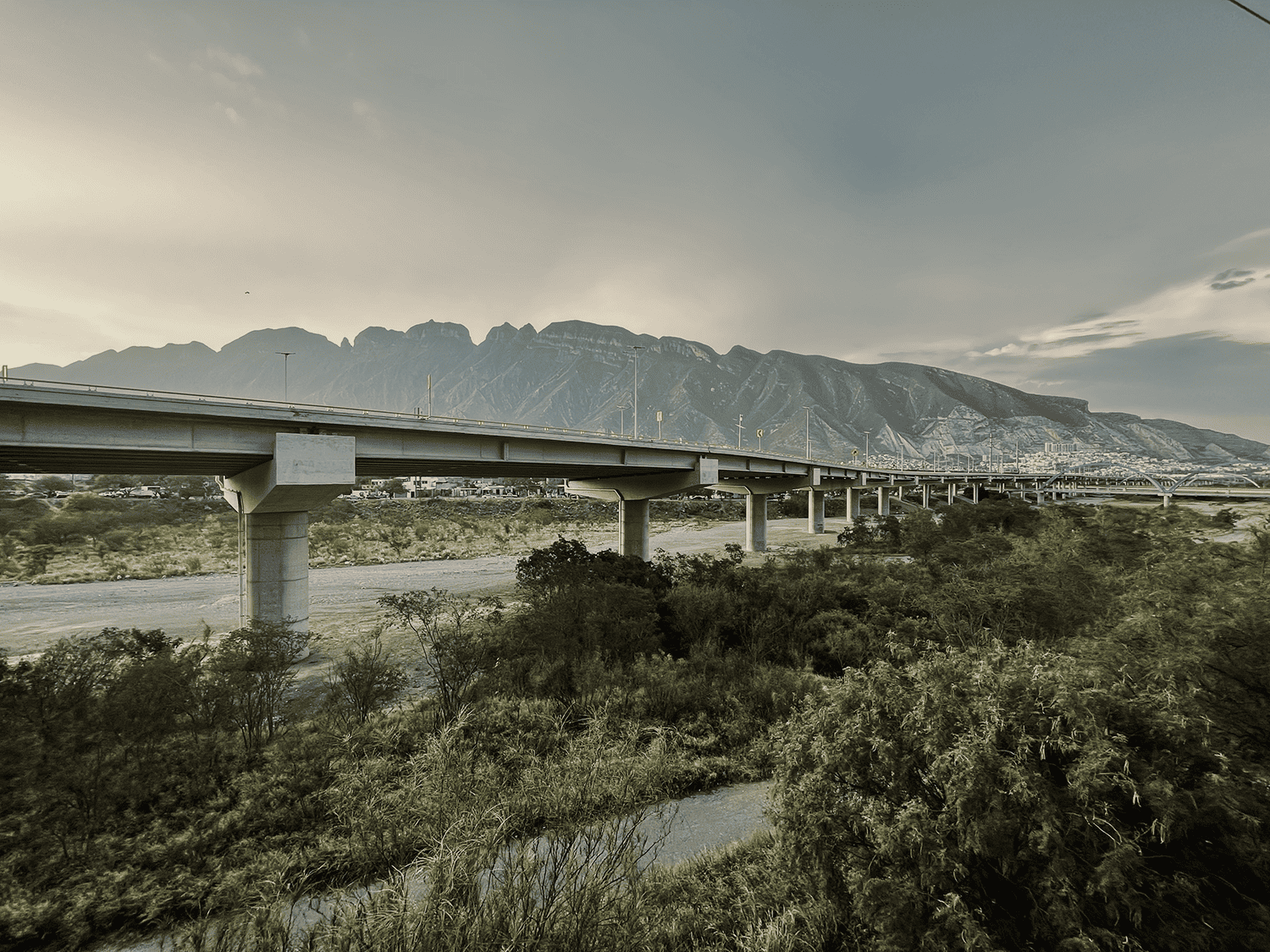

Like many other cities, Monterrey is not prepared for a warming planet with increased volumes of water in its atmosphere and extended droughts. The impervious urban ground that covers much of the city is designed to drain water as quickly as possible. Agriculture, industry, and citizens overexploit water unsustainably. As a result, during much of the year the Santa Catarina riverbed remains dry. Yet at times of heavy rain, it is prone to overflowing, with potential catastrophic results.

In the fall 2023 studio “AQUA INCOGNITA: Designing for extreme climate resilience in Monterrey, MX,” GSD Design Critic Lorena Bello Gómez worked with students to devise design strategies along the Santa Catarina watershed to increase water security and to reduce flood risk. Bello was invited to Monterrey after her work on the first iteration of AQUA INCOGNITA, in 2021 and 2022, which focused on the Apan Plains, a region that shares a basin with Mexico City and also struggles with its water supply.

For Bello, every studio is an opportunity to expose students to real-world climatic problems and inspire efforts to restore a lost balance with the water cycle. “Traveling with students for field research and engagement is a fundamental part of the pedagogy,” she explained. “The territorial scale of a project dealing with water risk in an urban region through the lens of an urban river, requires the ability to constantly telescope from macro to micro scales.” According to Bello, digital tools like Google Earth and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) cannot recreate the experience of “inhabiting and crossing the river with your own feet to understand its ecology and scale, and that of its surrounding infrastructures.”

Bello’s focus on the Santa Catarina River watershed developed through a yearlong engagement with the regional conservation institution Terra Habitus, which sponsored the studio. In addition to giving students firsthand experience, Bello’s studio was also an opportunity to help those fighting to change the status quo on the ground. “Deciphering where to insert the needle in this impervious skin is the first incognita to solve,” Bello said. “We know that there is the potential to recover this river as an ecological corridor and climate resilience infrastructure for the city, but we also need to know that there are local academics, organizations, and citizens that could benefit from our work to push the political will.”

Bello’s fieldwork in advance of the studio included meetings with a variety of stakeholders. She gathered input from representatives of community groups and planning agencies as well as political leaders such as Monterrey’s mayor, Donaldo Colosio, and the mayor of neighboring San Pedro Garza García, Miguel Treviño. She also met with Juan Ignacio Barragán, the director of the local water operator Servicios de Agua y Drenaje de Monterrey. Other important preparation included a Spring 2023 research seminar, “Resilience Under New Water Regimes: the case of Monterrey Day-Zero”, supported by PhD candidate Samuel Tabory (PhD ’25).

Daniella Slowik (MLA II ’24) chose to take the studio because she is already focused on climate- and water-related projects and sees herself working on these topics after she graduates. “Different parts of the world are going to continue to experience massive extremes,” she said, “and we have to learn how to work within those constraints in our design field.”

Students toured the riverbed with two local conservation groups as soon as they landed in Monterrey. They examined the soil and plant life in a dry section of riverbed running along one of Monterrey’s major highways before visiting Los Pinos, an informal settlement along the river. Locals shared memories of playing soccer, riding motorbikes, or attending parties on the riverbed, but they also expressed their new understanding of the river as a unique healthy ecology in otherwise desertifying Monterrey. The value of being on the ground, as Bello said, was in “sensing citizens’ empathy towards its river when they walk with us, learning about agricultural practices in the mountains, or understanding from local experts on policy and cultural challenges to overcome.” She continued, “This physical and personal exchange propels students’ imaginations, while their questions make locals aware of hidden aspects that they were overseeing.”

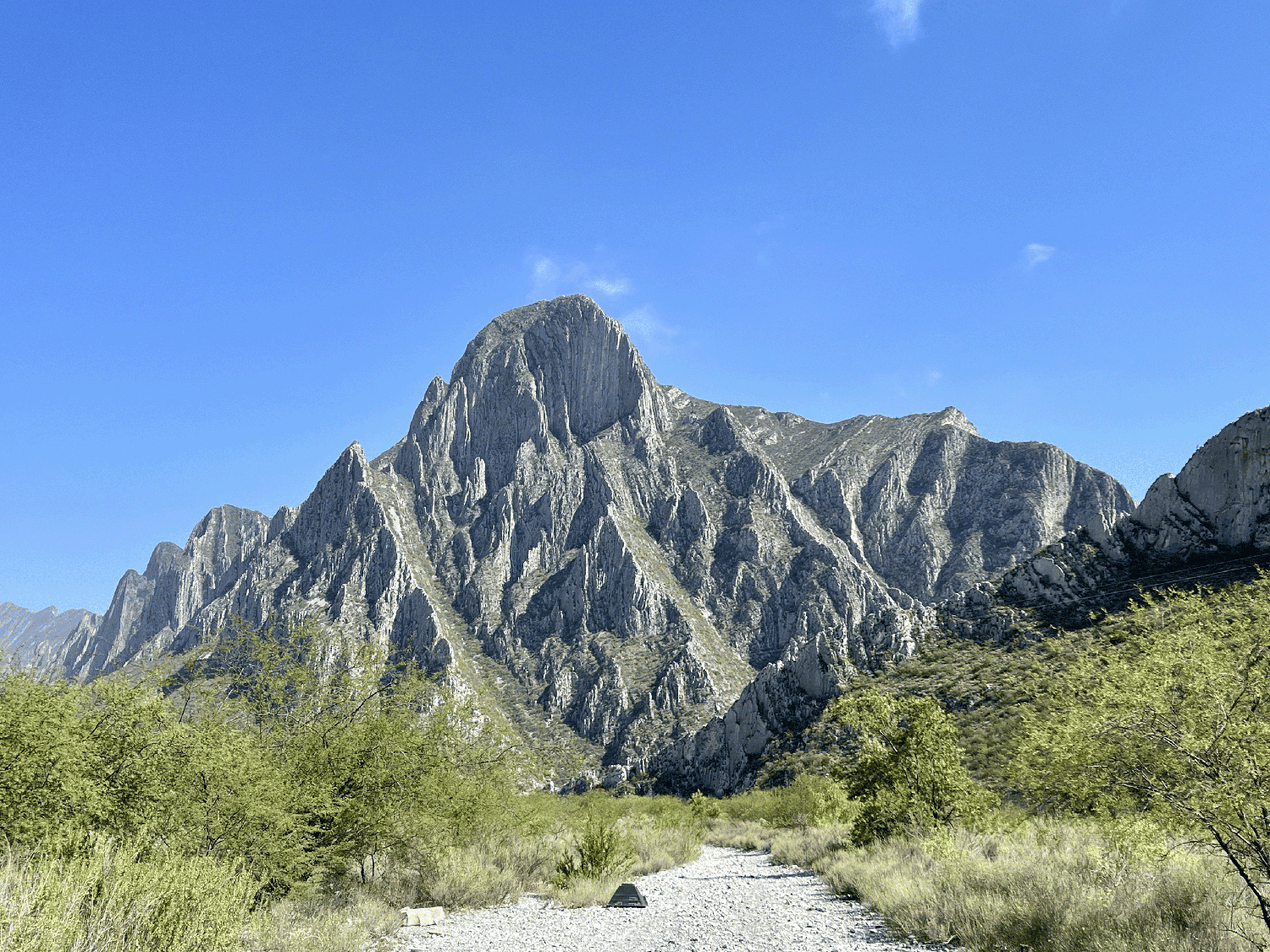

The group later drove to La Huasteca, the first canyon in the Parque Cumbres National Park in the nearby mountains that is the source of the Santa Catarina. The area has also become a site of unregulated settlements despite its protected status. “Traversing the lengthy river,” Bello explained, allowed students to “understand the duality between its urban condition downstream—today a flood-control channel—and its powerful upstream condition along the monumental Huasteca and Cumbres National Park, or by its flood control dam Rompepicos.”

The studio also spent several days participating in the Urban Hydrological Adaptation symposium and workshop sponsored by the Tecnológico de Monterrey with GSD former graduate Ruben Segovia (MArch II ’17). Organized by Bello and Segovia, the gathering of architects, landscape architects, and other academics built on conversations she had at the Tec de Monterrey on her previous fieldwork visits. Over the course of several days, students presented case studies of other cities with rivers that they had prepared earlier in the semester.

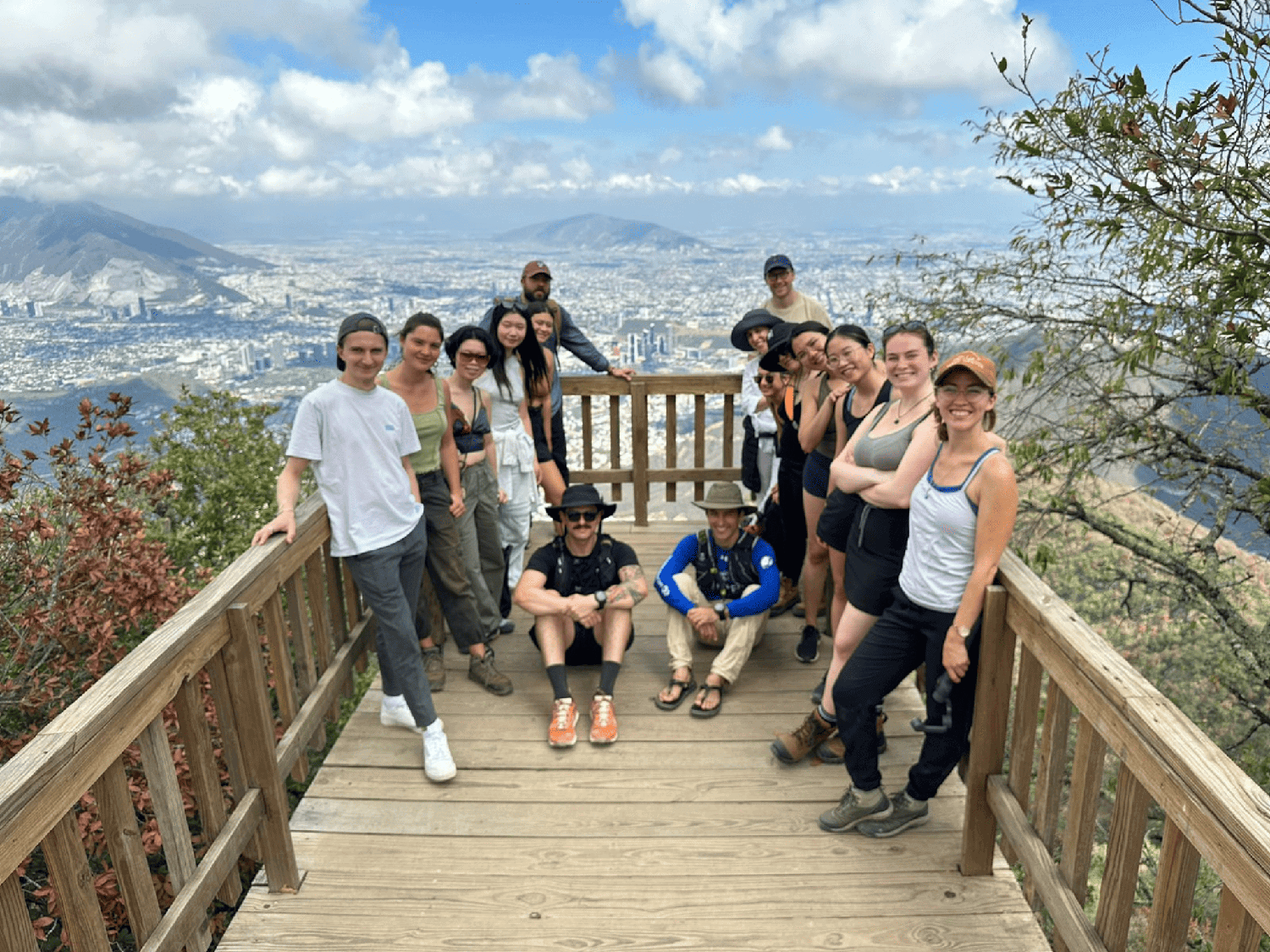

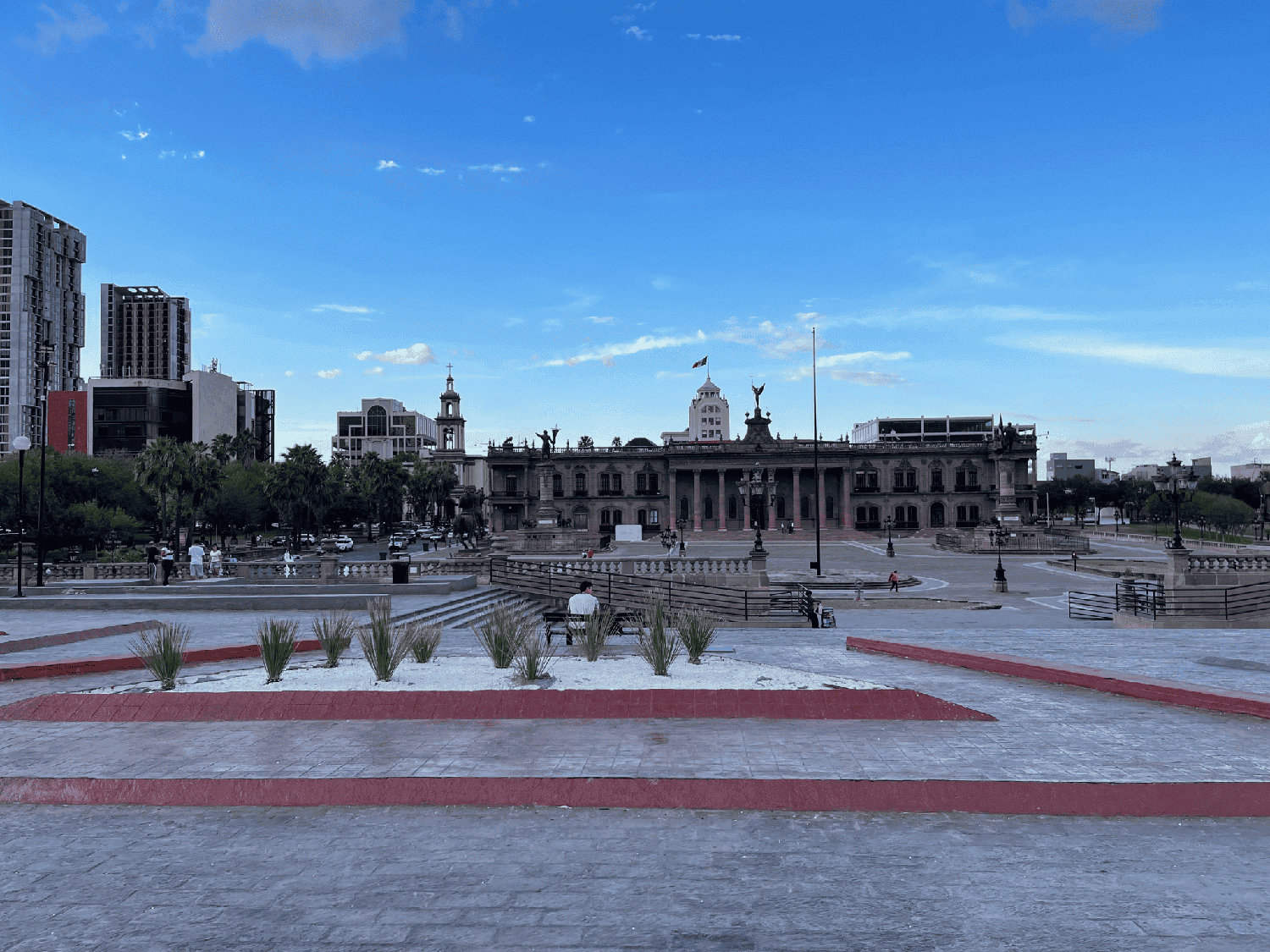

Several afternoons were devoted to site visits to locations ranging from parks such as the upscale Paseo San Lucia, an artificial canal offering boat rides, to Centrito, a neighborhood in the process of being rebuilt, where the group navigated several blocks of construction sites in 95-degree heat. A highlight that was both fun and educational was a hike in Chipinque National Park, which offered breathtaking views of the Sierra Madre Oriental and the ability to view the city within the context of the mountain landscape.

Inspired by the knowledge gleaned from the site visits and motivated by meetings with representatives from the municipalities of Monterrey and nearby San Pedro to address urgent needs, students’ final projects displayed a variety of alternative futures for the Santa Catarina River. While working individually, they also tackled collectively the myriad of challenges to overcome at the Rompepicos flood control dam, at the Cumbres National Park, and along the Santa Catarina River from the Cumbres to the urban park Fundidora. The final projects displayed a wide variety of solutions. Some students chose to center their work on the mountainous area around La Huasteca; others took as their focus the highways or parks closer to the urban center. (See an overview of the projects below).

As climate change becomes an unavoidable concern in the design disciplines, the GSD’s Department of Landscape Architecture has pledged its “abiding commitment to climate mitigation and adaptation through its curriculum, faculty research, and design culture.” Indeed, many students cited the urgency of climate change as a primary reason that they chose this particular studio. Bello’s career has also focused on climate. In addition to her previous research in Mexico, she has used her background in landscape, architecture, and urbanism in her work with environmentally vulnerable communities in India, Colombia, and Armenia. Weather permitting, she says with a smile, she plans to expand the Monterrey studio next fall.

For the final review, students presented their work in a sequence arranged geographically along the river transect, presenting the different challenges and opportunities to overcome by design such as:

Reciprocity at Cumbres National Park

- Jianing Zhou (MLA II ’24)’s project proposes an alternative network of almost invisible “incognito dams” as a counterpoint to mega-projects meant to control flood risk

- Emily Menard (MLA II ’24) explores reciprocal relationships between those who visit and inhabit the park, towards a more mutualistic and regenerative land use for water conservation

The ephemerality of flooding

- Lucas Dobbin (MLA I AP ’24) created “room for the river” at a key bend and point of risk inflection for extreme water flows entering the city from Parque Cumbres

- Pie Chueathue (MLA II ’24) uses the time in between floods to introduce a temporary/light-footprint tree nursery to promote urban tree canopy and work

Vertical and horizontal capillarity

- To reduce flood risk in the larger watershed, Boya Zhou (MLA I AP ’24) proposed starting to recover the network of streams while reconnecting them to the urban fabric

Circularity

- Responding to the near-shoring boom in Monterrey, Sanjana Shiroor (MAUD ’24) explored principles of circularity for brownfields along the river’s corridor to counter low-density sprawl

Bridging and descending to bring the edge of the city to the river

- Ashley Ng (MLA I ’24) designed a promenade

- Sophie Chien (MLA I AP/MUP ’24) proposed an inhabited bridge

- Using bridges as a river entrance to descend to a newly terraformed riverbed, allowing for habitat and inhabitation between storms, was the design vision of Annabel Grunebaum (MLA I ’24), Miguel Lantigua Inoa (MArch II/MLA I AP ’24) and Bernadette McCrann (MLA I AP ’24)

Climate justice

- Daniella Slowik (MLA II ’24)’s project emerged from a deep engagement with the history of Independencia, a marginalized community near the river, and asked what it would mean to convert the river into a community asset rather than just a source of vulnerability and risk