On the southern coast of Taiwan, groundwater pumped from the earth flows through dense tangles of pipes to supply industrial-scale fish farms. This intensive aquaculture has had a dramatic effect on the surrounding land of Pingtung County. Daniel Fernández Pascual, winner of the 2020 Wheelwright Prize, noted that the pumping of groundwater has caused some areas to sink 6 to 8 centimeters each year. Speaking at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in March, Fernández Pascual described how “buildings keep losing their ground floors. Living rooms become garages. Doors become stairs. Roofs touch the street.”

Taiwan’s fish farms exemplify the “extractivist” logic of aquaculture—and its long-term consequences. Pingtung County is one of the areas that Fernández Pascual studied during his Wheelwright term, which brought him in contact with coastal communities in ten countries, from the Isle of Skye in Scotland to the shores of Chile to coastal towns in China. The $100,000 award enabled him to take a global perspective on the risks of intensive aquaculture while identifying alternatives that could become the basis for a sustainable future. Resisting extractivism, Fernández Pascual aimed to foster a “tidal commons,” which he defined as a “framework of shared assets and shared stewardship of ecological structures in the planet’s shoreline.”

The title of Fernández Pascual’s talk, “Being Shellfish: Architectures of Intertidal Cohabitation,” reflects the central place of oysters, mussels, scallops, and other bivalves within his vision for the tidal commons. “Oysters filter the sea,” he said, “and in so doing their shells record histories of coastal habitation as material witnesses of the Anthropocene.” The natural habitats of these creatures comprise the same coastal regions that fish farms can spoil. “Bivalves and other foods have been a tool for us to understand the impact of intensive food production,” Fernández Pascual said, “while also supporting the different struggles and solidarity networks across communities in the ruins of extractivism.”

The scope of Fernández Pascual’s research extends far beyond encouraging the consumption of more ethical seafood—though bivalves are indeed tasty, sustainable alternatives to farmed fish. At the GSD, he put forward a holistic vision for new models of economic development and strategies for navigating a changing climate. In addition to rethinking food supply chains, bolstering restaurant menus, and undertaking educational initiatives, “intertidal cohabitation” means harvesting resources, such as shells and seaweed, that have long been used in traditional building practices and imagining new uses for them in the present.

Fernández Pascual may be best known for his collaborations with Alon Schwabe as Cooking Sections. Their work, often featured in international biennials, includes performative meals that foreground urgent ecological questions. CLIMAVORE, one of their research initiatives, aims to “transition to alternative forms of nourishment in the climate crisis.” In 2017, ATLAS Arts, a cultural organization based in Skye, Raasay, and Lochalsh in northwest Scotland, invited Cooking Sections to the area, where salmon farming dominates the local economy. Fernández Pascual and Schwabe developed a project that eventually became a long-term engagement with the community. One aspect of their work is an installation constructed from metal oyster cages. Built in an intertidal zone, the structure is submerged at high tide and inhabited by bivalves. At low tide, it becomes a communal table for the performative meals that Cooking Sections organizes as well as a public forum for discussions and workshops.

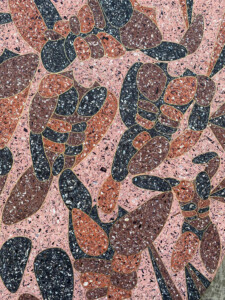

One fundamental question raised at these forums is how the economies of Skye, Rassay, and Lochalsh might transition away from fish farming. Enhancing the role of bivalves in the food supply chain is part of the answer. At the GSD Fernández Pascual also highlighted potential uses of oyster shells as building materials. He has been collaborating with a team to create tiles from oyster shells that have been cleaned, ground up and processed. A pair of murals depicting bivalves that he and Schwabe created demonstrate the potential of this material. They employed similar techniques for Oystering Room (2020), their contribution to the 2020 Taipei Biennial. Visitors to the installation could recline in lounge chairs crafted in a material inspired by a Taiwanese technique of mixing oyster shells, glutinous rice, and maltose sugar to create a binding paste. Visitors could also sample an exfoliating skincare product derived from oyster shells—a luxurious demonstration of how bivalve cultivation could counter the sinking economics of fish farming.

Oyster shells have long served as a source of fertilizer and as a key component of tabby concrete. Fernández Pascual surveyed building traditions in Southern China, where oyster shells are employed directly as siding, as well as in Japan, where walls made of oyster-derived plaster keep interiors well ventilated. Seaweed harvested from intertidal zones has also served as roofing material in Denmark, China, and elsewhere. In revisiting these traditions Fernández Pascual was not attempting to recover a lost pastoral ideal. The goal is “cohabitation” in the present, a concept that challenges us to “learn how to produce an ecological future that enables us to live well beside toxicity and unstable, shifting seasons.”

In gathering information from around the world, Fernández Pascual also facilitated a global exchange of information about what learning to live beside toxicity might mean. “Research conducted as part of the Wheelwright Prize has tied together different experiences from communities dealing with pollution from intensive farming,” he said, emphasizing how these communities were interested in “sharing lessons on collective usership of the coast and architectures of intertidal stewardship and resistance.” While the Wheelwright Prize supports such an international outlook, Fernández Pascual’s award was announced just as the world shut down due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Speaking about his research process prior to his public talk, Fernández Pascual noted the importance of local collaborators, many of whom he contacted remotely. “Especially when we’re talking about extractivism,” he said, it’s vital to ensure that you “don’t become extractive in the research.” The ethics of working as “the outsider coming to learn,” especially during the pandemic, were at the forefront of Fernández Pascual’s process.

The pandemic also altered the focal point of the project. Initially, Fernández Pascual and Schwabe envisioned restoring a building on Skye that could serve as a permanent hub for their Climavore work. Yet with rural real estate in high demand, the project fell through. This shift proved fortuitous, however, allowing the project to take the form of an “assemblage of formats” that span different practices and fields of knowledge while engaging a wider range of stakeholders, from educators to activist groups to chefs. “Precisely because we did not have to take care of a building,” he said, “we could rethink allyship and make the project much more open and diverse.”

This fluid approach also forced Fernández Pascual to take an expansive view of his own role as a designer, researcher, artist, and activist. He described learning “how to jump boundaries across disciplines, especially when talking or thinking about the food supply chain.” His research incorporates vernacular techniques and technological innovation in material projection. “There are many networks of knowledge involved in figuring out what it means to live besides toxicity and to imagine an alternative scenario,” he said, encouraging design students in particular to look beyond their disciplines to “find the necessary allies to join in the quest for alternatives.”