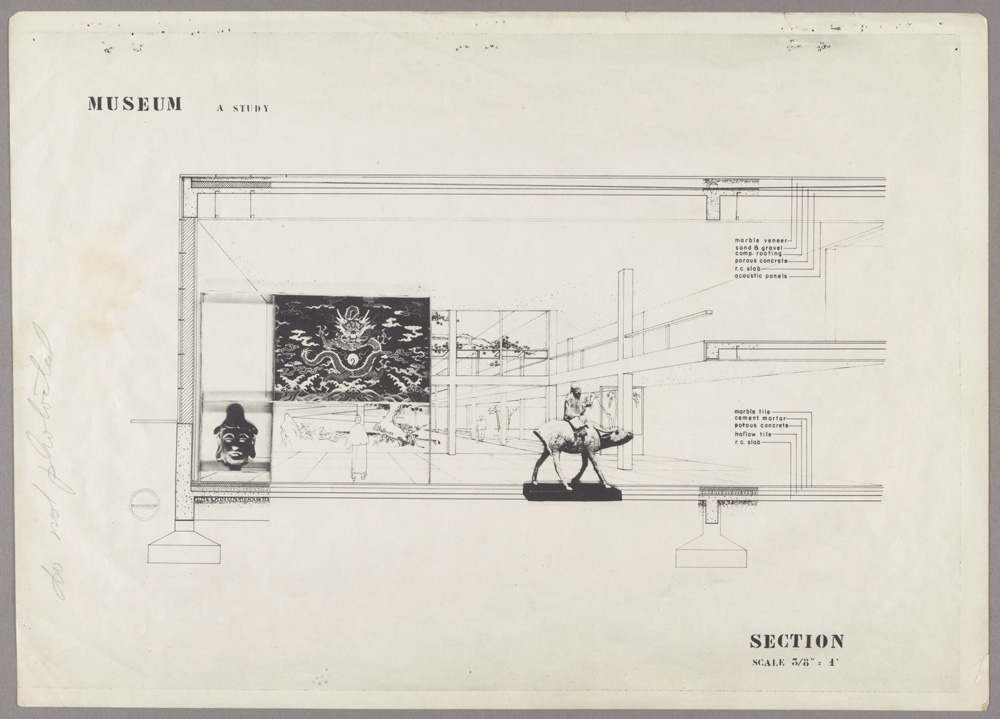

For his 1946 thesis at Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), Ieoh Ming (I.M.) Pei proposed a museum in Shanghai. Intended to display Chinese art, the structure embodies a proposition about the changing nature of cultural and civic institutions in the cosmopolitan city where Pei spent his early life—a city that had since been transformed by war and was on the verge of revolution. The project’s modernist form attests to Pei’s time studying under Walter Gropius while its spatial layout, organized around courtyards, recalls precedents in Chinese architecture. Such subtle transcultural sensitivity characterizes Pei’s six-decade career, which is now set for a major reassessment.

“He was always interested in trying to find buildings that would enliven the community in which they existed,” said I.M. Pei’s son Li Chung (Sandi) Pei (AB ’72, MArch ’76). On May 15 at Cooper Union in New York, Sandi Pei shared reflections on his father’s life and work with Calvin Tsao (MArch ’79) in a conversation moderated by architecture critic Paul Goldberger.

The event, organized by the M+ American Friends Foundation, previewed the architect’s first major retrospective, I.M. Pei: Life is Architecture, opening this summer at M+ in Hong Kong. Curated by Aric Chen and Shirley Surya, the exhibition has roots at the GSD, where “Rethinking Pei: A Centenary Symposium” took place in 2017. Several of the papers presented at the symposium have been adapted for the publication that accompanies the exhibition.

Sandi Pei and Tsao shared memories of working with I.M. Pei on now-seminal projects. Tsao joined the firm Pei Cobb Freed as a fresh graduate of the GSD. He jokingly recalled how, as a junior staff member, he received an assignment “counting bathroom tiles” for the design of the Javits Center. Yet his work eventually caught the attention of the firm’s principal, and Tsao joined the project team for the Fragrant Hill Hotel in Beijing, one of the first significant international projects developed during the period of economic reform in China.

I.M. Pei was as adept at navigating the world of New York developers as he was in conveying his design philosophy to members of the public where he worked. Both Tsao and Sandi Pei had roles on the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong, a building notable for its imposing structure of triangular supports designed to withstand typhoon winds. Yet as Tsao recalled, I.M. Pei understood the skyscraper in terms of a Chinese saying, “the bamboo shoot rising ever higher under the spring rain.” As Tsao said, “It’s not just technical engineering, but also it derived from that cultural, literary context.” Tsao also recalled Pei sharing Chinese landscape paintings as part of the design research process for the Fragrant Hill Hotel.

2021. Commissioned by M+, 2021. © South Ho Siu Nam

I.M. Pei did not return to the academy after he started his practice, but as Sandi Pei noted, “we often said working in the office was like being in a university,” with employees earning a rigorous “I.M. degree.” He recalled his father bringing strong ideas to a project but also allowing them to evolve through the design process, often with crucial input from others, as on the CAA building in Los Angeles. “He felt that the way to teach was through his buildings,” said Sandi Pei, “and he welcomed people to look at what he was doing and challenge the ideas.” As Tsao added, “I think he would make an incredible teacher. Not one who lectures, but someone who could actually sit side-by-side with you.”

While the panelists shared such candid reflections on the man who mentored them, they also alluded to another side of I.M. Pei as a public figure and veritable diplomat responsible for high-profile projects like the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., and the renovation of the Louvre in Paris. Almost transcending his role as an architect, Pei courted political favor from successive French politicians and American elites, including Jaqueline Kennedy (one section of the M+ exhibition is titled “Power, Politics, and Patronage”.)

Yet one member of the audience voiced a question that was also raised at the GSD symposium: despite his legacy of iconic buildings, is I.M. Pei, in fact, underrated? “In the Venn diagram of architects who work for developers and architects who are widely admired,” Goldberger speculated, “I think there’s only one tiny bit of overlap”—just enough for I.M. Pei. The architect’s once-controversial decision to work for the real estate developer William Zeckendorf early in his career is one of the prime areas ripe for reassessment today. A study of Pei’s business acumen, as a complement to his visionary designs, suggests in particular possible strategies for the development of high-quality affordable housing.

© Marc Riboud/Fonds Marc Riboud au MNAAG/Magnum Photos

As Sandi Pei noted, this experience with Zeckendorf was a crucial foundation for later projects and allowed him to build a professional network that eventually served as the basis for his own firm. “He did many low-cost housing buildings,” Sandi Pei said, which “allowed him to explore the possibility of using reinforced concrete in a way that was cost-competitive with brick buildings. By using new technologies, and new structural engineering techniques, he was able to really advance the housing as a result.” With a focus on large-scale housing, I.M. Pei had less interest in single-family private dwellings, though the retreat he built for his own family just north of New York is a stellar, if under-known, example, which Goldberger ranked alongside Philip Johnson’s Glass House and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House.

Based in New York, I.M. Pei maintained strong ties to Greater China. During a Q&A session, one audience member spoke of his influence as a prominent Chinese American figure whose culture-spanning influence transcended the profession. Almost exactly 60 years after his GSD thesis project, Pei, working with his sons, opened a museum for Chinese art in Suzhou, China. With gallery spaces defined by fundamental geometry and arranged around a network of courtyards and gardens, the project exemplifies aspirations that Pei held throughout his career.