In 2017, the Harvard Graduate School of Design hosted a conference co-organized with M+ museum in Hong Kong on the legacy of architect I.M. Pei, who graduated from the School in 1946. Last month, M+ opened the retrospective exhibition I.M. Pei: Life is Architecture. The following essay by Barry Bergdoll, Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History and Archaeology at Columbia University, is an excerpt from the publication that accompanies the show, published by Thames & Hudson. It has been edited slightly for this context.

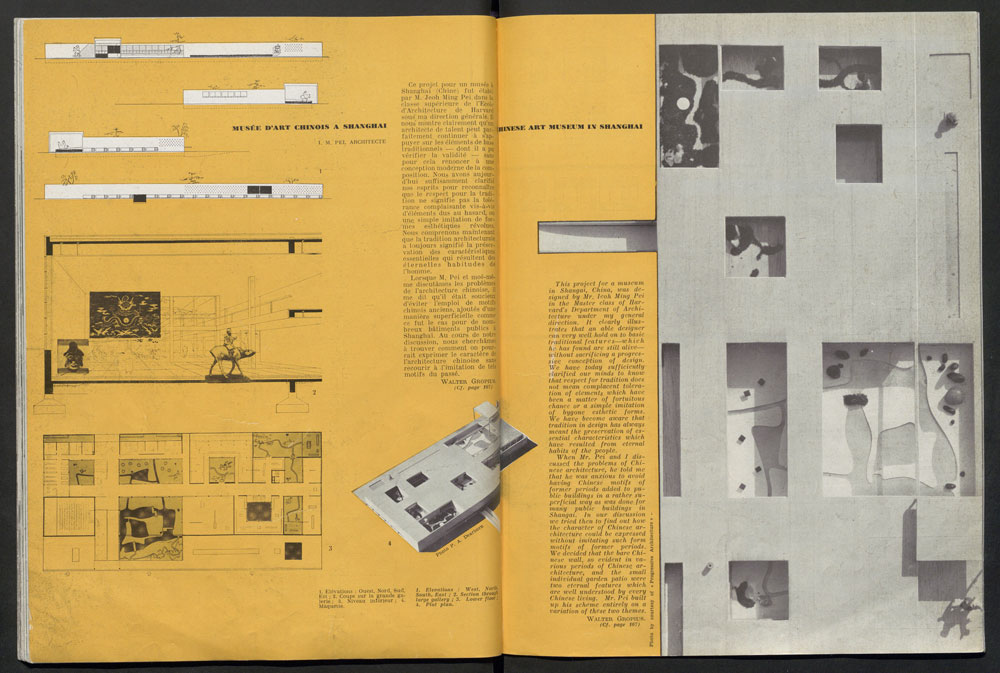

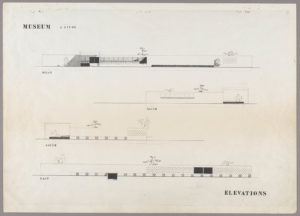

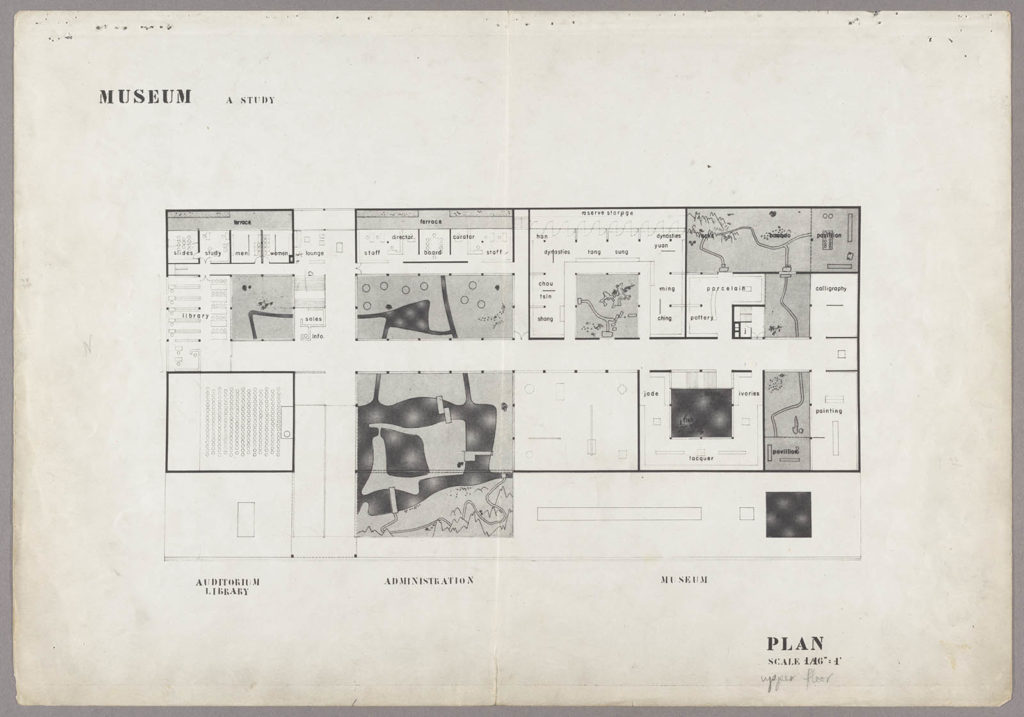

In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, I. M. Pei concluded his stellar progress through the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) with a thesis project that marked an original position in debates of the period over the renewal of civic space and on the form of a modern museum. Pei’s choice of subject, a museum of Chinese art for Shanghai, made clear enough his ambition to take his new design training home to his native China and to contribute to debates on the appropriate form for a modern Chinese architecture. With this choice, he raised the fascinating question of cultural relativity: does Chinese art require a distinctive type of architectural frame for viewing? This question extended the then current debate among architects and museum curators over whether or not modern art was better shown in new types of spaces. In his complex, two-story frame of widely spaced reinforced-concrete piers, featureless so as to make reference neither to Western colonnades nor to Chinese timber traditions, Pei proposed a museum space that was as much community center as museum, and equally as much landscape, with its garden flowing through the building and interior tea pavilions. Pei’s remarkable design catapulted him onto the international stage—before he had ever built a building—when his thesis project was published in two of the leading architectural journals of the day: Progressive Architecture in New York and L’architecture d’aujourd’hui in Paris.¹

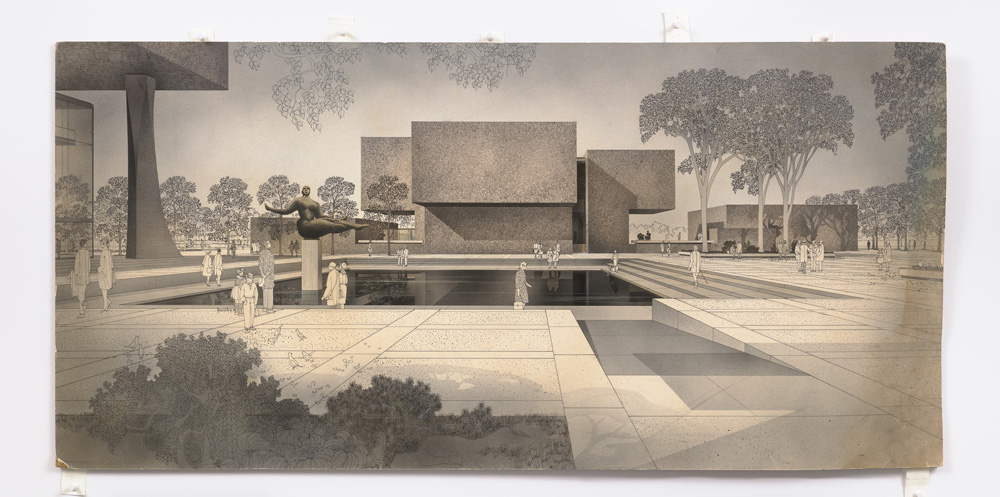

Courtesy of Bibliothèque d’architecture contemporaine – Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine.

Pei had left China at a moment when Shanghai was in the throes of discussing the creation of a new civic center, of which a museum would be a key component. Throughout his studies in the United States, Pei had kept an eye on the situation at home, even during the height of the war. His undergraduate thesis project at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), submitted in 1940 and titled “Standardized Propaganda Units for War Time and Peace Time China,” was in essence a design for an itinerant cultural center to be deployed by the “Ministry of Propaganda” in rural areas. The design paid homage in its tensile structures as well as in its conception of cultural propaganda, referring to both Soviet revolutionary architecture and Le Corbusier’s Pavillon des temps nouveaux at the Paris Exposition universelle of 1937.²

Early on, Pei viewed architecture as an impetus for cultural transformation and community-building, with a sense of the urgent need to contribute to a spirit of nationalism in a country resisting Japanese invasion. In the text accompanying his MIT thesis, he underscored the political and social basis of his design with technical descriptions of the system of lightweight bamboo construction uniting Chinese tradition and a burgeoning interest in prefabrication. Two aspects of this project are relevant for his decision six years later to design a museum for Shanghai: the fact that the space would be modifiable, with equal weight given to exhibitions and to theatrical events, and that bamboo could be used in a mixed assembly to become a modern structural material, locally available and relying on existing labor know-how. Pei proposed a largely open-plan space with flexible partitions, notably so that the space could be changed from a darkened theatre to a light-filled display.³

When Pei enrolled at the GSD in December 1942—only to interrupt his studies almost immediately to work for the National Defense Research Committee in Princeton—his young wife, Eileen, was already studying landscape design there. Art periodicals were filled with articles on the need for museums to respond to the challenges of modernist art and of a changing society. In New York, Alfred Barr Jr, founding director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), conceived of an entirely different concept of a museum and of its architectural space, influenced by his first-hand experiences at the Bauhaus and with the experimental installations undertaken by Alexander Dorner in Hanover in the late 1920s. After Dorner’s emigration from Hitler’s Germany, Barr was instrumental in finding him a position as director of the Museum of the Rhode Island School of Design. With his concept of the “living museum,” Dorner promoted museums as active parts of a community. Walter Gropius, likewise newly installed in the United States, would frequently assign museums and cultural facilities as studio assignments at Harvard.

In 1939, MoMA opened in its permanent home—a building designed by Philip Goodwin and Edward Durell Stone that represented a radical departure from the neoclassical temple type most recently promoted for a new national gallery of art in Washington DC. At MoMA, Goodwin and Stone discarded the conventions of classical columns in favor of a translucent curtain-wall facade, transparent on the ground floor to allow views from the street. Visitors entered at ground-floor level rather than ascending a flight of ceremonial stairs; they also had immediate access to an outdoor sculpture garden behind the museum that could be seen from the street through the glazed vestibule. Transparency and flexibility were to be hallmarks of a new generation of museums, qualities that were soon seen as echoing the stakes of national cultural politics. In his radio broadcast on the opening of MoMA’s building, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared: “As the Museum of Modern Art is a living museum, not a collection of curious and interesting objects, it can, therefore, become an integral part of our democratic institutions—it can be woven into the very warp and woof of our democracy.”⁴

In 1943, two radically new, if diametrically opposed, visions of a future art museum were proffered by Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe. Wright had drawn up a variety of schemes for the future Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s famous spiralling ramp suspended above an open ground floor penetrable from the street by both pedestrians and vehicles. In September 1945, as Pei was returning to complete his graduate work at the GSD, Wright’s model was unveiled at the Plaza Hotel and heralded in the New York Times: ‘Museum Building to Rise as Spiral, New Guggenheim Structure Designed by F. L. Wright Is Called First of Kind’.⁵ Few knew that Le Corbusier had been working on a similar concept since 1929, although it is likely that, given Pei’s enthusiasm for Le Corbusier, he was familiar with the project, titled Musée à croissance illimitée, which had been published in 1937 in the first volume of the architect’s OEuvre complète.

In 1943, Architectural Forum published a special issue of designs by leading American architects that posited the form and institutions of a post-war city under the rubric “194X,” since no one knew when the Second World War would come to an end. Together with its parent publication, Fortune, the magazine modeled all aspects of a medium-sized post-war city, choosing Syracuse, New York, imagined as if it had been bombed. Fortune proposed the economic and social dimensions of the city and Forum its architecture and urban layout, including a civic center where city hall and museum would be brought into a taut composition at the core, something with echoes of the Greater Shanghai Plan debated during Pei’s high-school days in China.⁶ The future museum was entrusted to Mies van der Rohe, whom Architectural Forum called the nation’s chief “exponent of the ‘open’ plan.”⁷ Ironically, Syracuse would be remodeled in the 1950s and 1960s by bulldozers in the name of urban renewal, rather than by German or Japanese bombs. Syracuse’s new Everson Museum of Art would be designed not by the elder statesman Mies—then at work on a new museum for West Berlin—but by the virtually untried Pei.⁸

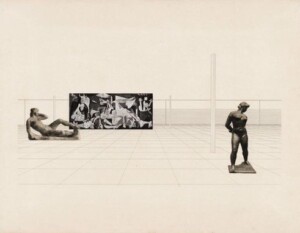

To represent new display conditions for modern art, which had discarded all the perspectival traditions of painting, Mies used collage, a method that had become his standard teaching technique for the courtyard house projects with students at Illinois Institute of Technology, and which Pei would emulate in his GSD thesis. Mies collaged photographs of works of art that might be displayed—poignantly Picasso’s Guernica, which depicts the horror of the Spanish Civil War—and enlarged color details of nature, cut to represent the uninterrupted view of the landscape from his glazed box. All is held in place in the collage by thin ruled pencil lines, which represent the delicate steel frame of the future structure. Most importantly, Mies’s building would be a new frame for looking at art from different vantage points. He writes: “A work such as Picasso’s Guernica has been difficult to place in the usual museum gallery. Here it can be shown to greatest advantage and become an element in space against a changing background.”⁹

Mies captured the larger ethos of the future city: “The first problem is to establish the museum as a center for the enjoyment, not the interment of art. In this project the barrier between the artwork and the living community is erased by a garden approach for the display of sculpture.” (This element of the project corresponds interestingly with the sculpture garden in Goodwin and Stone’s 1939 design for MoMA.) Mies concludes: “The entire building space would be available for larger groups, encouraging a more representative use of the museum than is customary today, and creating a noble background for the civic and cultural life of the whole community.”¹⁰

Both Mies’s design approach and his rhetoric would find echoes—emulation and critique—in Pei’s design for Shanghai. Pei’s project was published in Progressive Architecture in February 1948 together with a number of short texts, the editors noting that “This remarkable graduate-school project strikes us as an excellent synthesis of progressive design in addition to providing a much-needed architectural statement of a proper character for a museum today.” As background, they add: “Planned to replace an inadequate structure that occupies a site within the city’s new Civic Center, plans for which were completed in 1933, this design for a museum “befitting the dignity of the city of Shanghai” is developed as an integral part of the civic plan.”¹¹

Published under Gropius’s guidance, the project is accompanied in both Progressive Architecture and L’architecture d’au jour d’hui by a statement from the former Bauhaus director that reflects some of his concerns in the 1940s, even if they perhaps overlook the extent to which Pei has taken on the museum debate that I am sketching in here. As Gropius explains:

[The project] clearly illustrates that an able designer can very well hold on to basic traditional features—which he has found are still alive—without sacrificing a progressive conception of design. We have today sufficiently clarified our minds to know that respect for tradition does not mean complacent toleration of elements which have been a matter of fortuitous chance or a simple imitation of bygone esthetic forms. We have become aware that tradition in design has always meant the preservation of essential characteristics which have resulted from eternal habits of the people.¹²

This text could apply as easily to Gropius’s relationship to New England clapboard houses as to Pei’s evolving vision of a relationship between Chinese tradition and modernity. “When Mr. Pei and I discussed the problems of Chinese architecture,” Gropius continues,

he told me that he was anxious to avoid having Chinese motifs of former periods added to public buildings in a rather superficial way as was done for many public buildings in Shanghai … We tried then to find out how the character of Chinese architecture could be expressed without imitating … former periods. We decided that the bare Chinese wall, so evident in various periods of Chinese architecture, and the small individual garden patio were two eternal features which are well understood by every Chinese living. Mr Pei built up his scheme entirely on a variation of these two themes.¹³

Pei designed a two-story concrete frame, entered by means of a dramatic ramp, cutting into it as needed to create sectional richness. The frame is clad in marble, an honorific befitting Shanghai’s civic center. The expansive roof is pierced with many more openings than those programmed by Mies in his steel frame and would be visible from taller buildings nearby, since the building is embedded in the ground by half a level. Influenced by both his wife’s study of landscape architecture and his own memories of the gardens of Suzhou, Pei weaves a garden through the open courts of the lower level. Gardens could be enjoyed both at eye level and from above, where the section of the building is opened to the sky. In place of Mies’s pictorialized landscape in the distance, Pei interweaves a commemoration of the garden as one of the high forms of Chinese art-making and considers it for use, labelling it a tea pavilion on the plan. He notes of the landscaped courtyards: “All forms of Chinese art are directly or indirectly results of a sensitive observation of nature. Such objects, consequently, are best displayed in surroundings which are in tune with them, surroundings which incorporate as much as possible the constituting elements of natural beauty.”¹⁴ As is clear from photographs of the model, now lost, Pei set out to capture the essence of Chinese domestic architecture using the courtyards, gardens, and semi-enclosed rooms that are present at every scale, from the hutong to the palace. “This section looks toward the entrance garden court, at right of which is a modern translation of the traditional Chinese Tea Garden,” the editors note. “Usually located in the market place, or near the temple grounds, to serve men of all classes as a social center and place for intellectual exchange, its inclusion here in a museum is with the hope that it will help make the institution a living organism in the life of the people, rather than a cold depository of masterpieces.”¹⁵ The incorporation of a Chinese-style garden, which fragments experience towards greater enjoyment, enlightenment, and discovery of multiple facets of reality, makes it clear that Pei was conscious of the ways in which Chinese pictorial traditions with nature or ink and brush often incorporate multiple perspectives, rather than the unified construct of linear perspective.

As Pei was designing a museum to take home, the civil war between Nationalists and Communists made an immediate return impossible. In the next few years, he would teach at Harvard instead, notably a foundation course, Architecture 2b: Architectural and Landscape Design, which clearly underscored the interdependence of building and site, construction and nature, and which also, according to the 1946 course bulletin, assured that “the social and economic factors underlying the design are constantly considered.” In 1947, Dorner was invited as a guest to work with students at the GSD on the design of a living museum. He took it as the occasion to pen a veritable manifesto on the role of the museum in relation to the specific spiritual state of mankind in modernity. The classroom brief was even reprinted in its entirety in Dorner’s influential The Living Museum: Experiences of an Art Historian and Museum Director, published in 1958, a year after his death. The brief also served as the point of departure for his 1947 book The Way Beyond Art. “The new type of museum,” he wrote,

would begin to partake of that energy [of the modern movement in art and architecture]. It would not only be more alive and stimulating but also much more easy to establish, for it would depend much less than the current type on quantitative accumulation, i.e. wealth. It would not require any gorgeous palaces of absolutistic ideal art but would be constructed functionally and flexibly of light modern materials … Like all new movements this new type of museum would then be an important factor in the urgently needed integration of life and in the unification of mankind on a dynamic basis.¹⁶

In his Museum of Chinese Art for Shanghai, Pei synthesized a series of concerns: his ongoing desire to intervene in the civic center in Shanghai, his commitment to imagining a cultural politics for his home country, and his attentiveness to the debate in the United States on the spaces and functions of an art museum. With its emphasis on landscape, the design possibly shows the influence of his wife, Eileen, who was at the time fully immersed in landscape architecture at the GSD. The first product of what would prove to be a lifetime engagement with museum design stood at the intersection of Pei’s memories of the cultural needs of pre-war China and the debates about the appearance of a post-war United States. When he was suddenly catapulted to national attention with an innovative built design for the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, his interest in changing perspectives on space was largely internalized. He created a building that could take its place not in dialogue with the larger liberated landscape but in the hard realities of an American city being reconceived for urban renewal. It was the first sketch in many ways of the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, where the Chinese émigré architect would be one of the first to bring a modernist vision of exhibition space to the landscapes of the American National Mall.

I.M. Pei: Life is Architecture (2024) is published by Thames & Hudson.

- “Museum for Chinese Art, Shanghai, China,” Progressive Architecture 29 (February 1948): 50–52; and “Chinese Art Museum in Shanghai”, L’architecture d’aujourd’hui 20 (February 1950): 76–77.

- Le Corbusier’s 1935 trip to the United States had an enormous impact on Pei, who recalled the Swiss architect’s visit to Cambridge as “the two most important days in my professional life.” See Gero von Boehm, Conversations with I. M. Pei: Light Is the Key (Munich: Prestel, 2000), 36.

- I. M. Pei, “Standardized Propaganda Units for War Time and Peace Time China,” BArch diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1940.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt’s speech was reprinted in full in the Herald Tribune (New York) on 11 May 1939, and can be found on the website of the Museum of Modern Art: https://www.moma.org/research-and-learning/archives/archives-highlights-04-1939, accessed 7 September 2021.

- New York Times, 10 July 1945, quoted in Hilary Ballon et al., The Guggenheim: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Making of the Modern Museum (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2009), 156.

- “New Buildings for 194X,” Architectural Forum (May 1943): 69–189. See also Andrew M. Shanken, 194X: Architecture, Planning, and Consumer Culture on the American Home Front (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000); and Barry Bergdoll, “Architecture of 194X,” in Mark Robbins, ed., American City “X”: Syracuse after the Master Plan (New York: Princeton Architectural Press with Syracuse Univeristy School of Architecture, 2014), 18–25.

- “Index of Projects and Contributing Architects,” Architectural Forum (May 1943): 72.

- On the Everson Museum of Art, see Barry Bergdoll, “I. M. Pei, Marcel Breuer, Edward Larrabee Barnes, and the New American Museum Design of the 1960s,” in Anthony Alofsin, ed., A Modernist Museum in Perspective: The East Building, National Gallery of Art (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 2009), 106–123.

- Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, quoted in “Museum, Mies Van Der Rohe, Architect, Chicago, Ill.,” in ‘New Buildings for 194X”: 84.

- Mies van der Rohe, ‘New Buildings for 194X”: 84.

- “Museum for Chinese Art, Shanghai, China”: 50–51.

- “Museum for Chinese Art, Shanghai, China”: 52.

- “Museum for Chinese Art, Shanghai, China”: 50–51.

- I. M. Pei, quoted in “Museum for Chinese Art, Shanghai, China”: 51.

- “Museum for Chinese Art, Shanghai, China”: 52.

- The winning project responding to Dorner’s brief to the Harvard students was by Victor Lundy, for a “Living Art Museum,” a design that clearly drew on Pei’s earlier project in its interweaving of a landscape garden under and through the spaces of a museum and its development of a partially sunken section.