Los Angeles’ Alameda Street cuts a north-south line through the city. Potholed by time, traffic, and freight trucks, the roadway stretches from Chinatown to the Port of Long Beach. At the northernmost end, the broad, commercial street marks a boundary between Little Tokyo, a pedestrian-scaled historic district of Japanese-American culture dating to the late nineteenth century, and the Arts District, a steadily gentrifying neighborhood where with each passing decade light industry gives way to artist studios, which are then replaced by galleries, restaurants, and new condo developments.

The two sides exist in a quiet equilibrium, connected by the Little Tokyo/Arts District metro station. In a metropolis often derided as traffic congested sprawl, this recently reopened underground hub for public transit links this corner of Los Angeles to the farther flung edges of the basin. For GSD associate professor of architecture John May, Alameda Street is a seam between two urban fabrics, each in states of considerable transformation.

This past spring, May led the option studio “The Temporary Contemporary: Assembling a Public in Downtown Los Angeles.” His course brief frames the stark, shadeless plaza around Little Tokyo/Arts District metro station as a “missed opportunity” for creating a space where folks might assemble—and that with such a gathering of bodies comes a vibrant connection of political and aesthetic life. “This does not imply that the content of aesthetic work must become explicitly political, but rather that ‘art’ (very broadly conceived) and the institutions where it is housed, can form spaces, arenas, and backgrounds for publics,” writes May in his introduction to the studio.

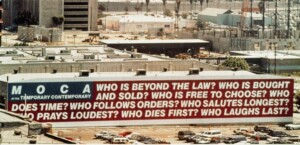

The Geffen Contemporary, a satellite of L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art, is located along Alameda Street and exemplifies the kind of institution May describes. On one side of the converted warehouse a message from Barbara Kruger— Untitled (Questions) (1990/2018)—queries passing drivers in all caps. “WHO IS BEYOND THE LAW? WHO IS BOUGHT AND SOLD?” her mural asks, demonstrating a necessary conflation of art, politics, and urban space.

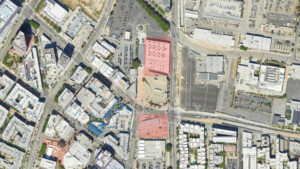

Conditions of publicness are embedded in the museum’s history, as is its ambiguous relationship to Little Tokyo. Although The Geffen Contemporary shares the block with the Japanese American National Museum, it is located at the end of a long pedestrian plaza, which serves both institutions, and is set back from the street. One of the challenges posed to students was to address the urban connection between the museum and the metro station, where they were to develop a mixed-use building designed to support a residency for performance artists. The program grew out of a very real necessity: Wonmi’s Warehouse is a 14,500-square-foot facility that is part of the Geffen Contemporary but only occasionally used for exhibitions.

Connected to MOCA, but originally a separate industrial structure, it was never outfitted for any specific program. Inflexible in its raw flexibility, the space lacks facilities, such as dressing rooms, showers, and rehearsal space. “[Associate curator Alex Sloane] described the warehouse as a space for bodies and the MOCA Geffen as a space for objects—in her view the warehouse is woefully inadequate for bodies,” notes May. As such, the bipartite brief reimagines two sites—the warehouse interior and the Metro station—to better accommodate invited artists, dancers, musicians and forge new understandings of audience.

May also suggests that performance art defies the financialization of the art market. As such, the art form itself is aligned with contestations in public space, be them aesthetic or political, both suggest a kind of urban choreography that manifests, draws people together, and then fleetingly dissipates. Artist Suzanne Lacy, writing in the 1995 collection Mapping the Terrain, outlines a trajectory of what was then termed “new genre public art”—artist and collectives like Judy Baca, Martha Rosler, and Ant Farm (Lacy’s examples) to Postcommodity, Crenshaw Dairy Mart, and the The Los Angeles Urban Rangers (mine) that engage urban space as a call to action. “This construction of a history of new genre public art is not built on a typology of materials, spaces, or artist media, but rather on concepts audience, relationship, communication, and political intention.”[1]

MOCA Geffen was initially conceived as an exercise in temporality. In late 1983 when it first opened as a provisional outpost, some 1,500 architects and designers showed up for a preview party. Los Angeles Times urban design critic Sam Hall Kaplan reported the movement of attendees as a “parade.” It’s easy to imagine this creative murmuration flocking to what was then called the “Temporary Contemporary,” to mingle, network, and ogle the pair of old warehouses renovated by Frank O. Gehry, then, as now, LA’s homegrown star architect.

The architect’s rising fame, coupled with his penchant for bricolage made him a perfect choice to tackle the 55,000-square-foot retrofit. His scrappy, light touch approach to the industrial building (originally designed by AC Martin in 1947) contrasted the studied postmodern geometries of Arata Isozaki’s plans for MOCA, which was then under construction on Bunker Hill and wouldn’t open until 1986.

The convening was orchestrated by a short-lived nonprofit, the Architecture and Design Support Group, whose mission was to raise design consciousness in the city. Kaplan was skeptical, writing in the LA Times, “The question raised by the group’s stated intent is how relevant the architecture and design exhibits and programs will be under the aegis of the museum, whether they will be just another forum for the new cadre of avant-garde architects and designers who are self-consciously pretending to be artists, or whether they will indeed help redirect the profession toward fulfilling its obligation as a social art to enhance the quality of life.”[2]

His critique, however narrowly cast, points to a larger concern, one echoed by the themes of The Temporary Contemporary studio: What is the agency of museums, of architecture to serve a community? The necessity of an architecture of assembly was made urgent during the racial reckonings following Black Lives Matter protests in 2020. In the years since, performance has emerged as a tool of rapid response—a means to bring underrepresented bodies into the institution and unsettle staid relationships between viewer and art. The venues where these performances happen are potentially transformative places.

May recasts the role of the museum from passive to active. His sentiments echo ones made decades earlier by Bernard Tschumi. “There is no architecture without action, no architecture without events, no architecture without program,”[3] wrote Tschumi in 1981, prefiguring Gehry’s Temporary Contemporary. Revisiting these ideas again, the architect was part of the jury for the studio’s final review in late April.

By imagining that MOCA might cultivate a spectrum of places along the public-to-private spectrum as site of free expression and refuges for queer, transgender, and BIPOC people—people often excluded or policed in public, The Temporary Contemporary studio envisions an architecture of resistance. Says May, “If we’re losing the right to protest and enact certain kinds of behavior in our ‘public space’, which isn’t really public, then maybe museums are going to have to take on this role more emphatically going forward.”

[1] Suzanne Lacy, Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art, Seattle: Bay Press, 1995, p. 28.

[2] Sam Hall Kaplan, “’Temporary Contemporary’ Agenda: Architects Tie Design Goals to L.A.” Los Angeles Times (1923-1995); Nov 25, 1983; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Los Angeles Times, pg. OC_C23.

[3] Bernard Tschumi, “Violence of Architecture,” Artforum, 1981. Accessed June 6, 2024. https://www.artforum.com/features/violence-of-architecture-2-215475/