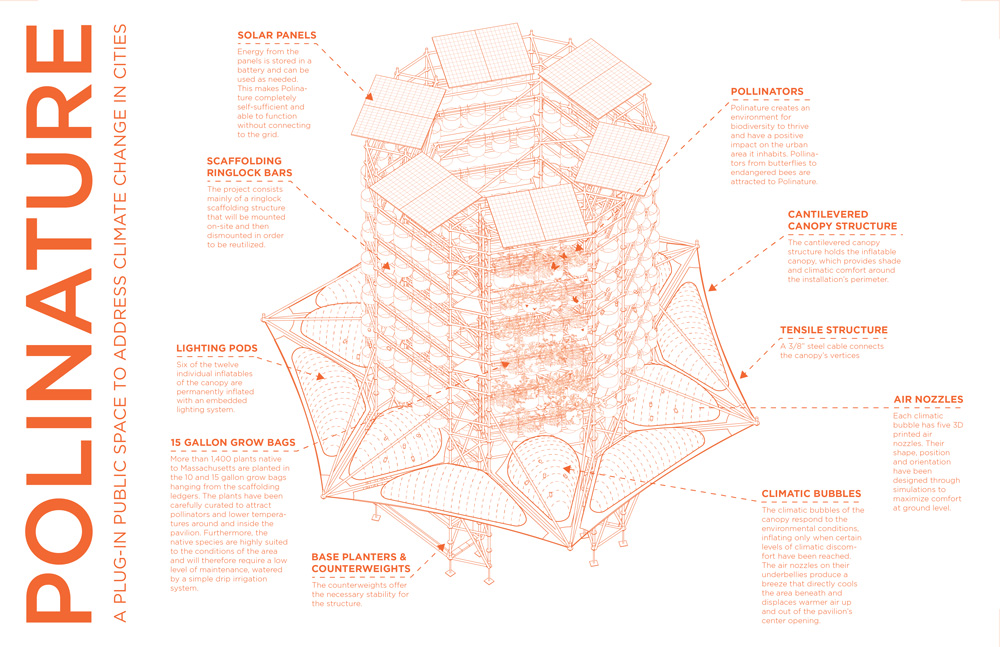

A vertical garden in the backyard of 40 Kirkland Street on the campus of the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) promises sanctuary to insects, relief from the late-summer heat, and new insights for how cities around the world can mitigate the effects of climate change. More than 1400 local plants hang in grow bags from a cylindrical scaffolding tower that rises nearly as high as the surrounding buildings. Titled Polinature, the project is spearheaded by Belinda Tato, associate professor in practice of landscape architecture at the GSD. “Polinature has been designed as a low-cost, low-tech temporary solution to bring climatic comfort to urban areas that currently lack it,” Tato explains in a text about the work.

Funded by the Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability at Harvard, Polinature is, on the one hand, harmonious with its immediate surroundings. Grown from seed in Massachusetts nurseries, the plants are similar to those found in yards and fields all over Cambridge, and the name refers to Tato’s aim of bolstering the local population of pollinating insects. On the other hand, Polinature has a singular aesthetic and self-sufficient function that sets it apart from its context. The steel tubes of the scaffolding and the counterweight system that keeps it stable attest to Polinature’s temporary status—the structure will be disassembled within a few weeks with minimal waste—while highlighting the project’s overall character, which is as much technological as pastoral.

Polinature is a machine for producing climate relief. Solar panels that cap the tower are capable of providing the project with its own source of off-the-grid electricity. In addition to powering digital displays with information about the project aims and data about Polinature’s climatic performance, the solar panels are adequate to support a set of twelve inflatable pods that ring the tower. Six of these pods are permanently inflated and embedded with LEDs to provide illumination. Another six are what Tato calls “climatic bubbles.” Apart from providing shade, these pods inflate and deflate in response to environmental conditions. Nozzles in the undersides of the climatic bubbles produce a cooling breeze for anyone below to enjoy.

For the past two decades, Tato has investigated how designers can address the deadly effects of heat in urban areas. Climate scientists have warned that cities are becoming hotter more quickly than rural areas, a divergence that is even more pronounced in megacities with populations over 10 million. “Urban greening” can play a role in mitigating these effects, though tree canopies dense enough to have a significant cooling function are often distributed unevenly, making excessive city heat a tangible index of social inequality.

Tato stresses that no single architectural intervention can compensate for the structural factors driving climate change. Still, Polinature has the potential to address acute dangers immediately while permanent solutions come to fruition. As a prototype, Polinature offers an opportunity to study “how the structure is creating a better climatic comfort in the space compared to the outside,” Tato says. Sensors placed inside and outside the structure provide comparative data, allowing Tato and her team to assess the project’s performance quantitatively and optimize it in future iterations. Polinature is the result of years of careful study, not only of the nature of the plants that are most suited to such a growing arrangement, but also of mechanisms that can modulate the airflow from the climatic bubbles, producing the perfect breeze.

Tato stresses that the Cambridge location, which was already verdant, is far from the end point for the project. “In an ideal world, this should have been placed on a parking lot,” she says. Polinature has the potential to provide instant urban greening and convert disused, asphalt-heavy areas into climatically comfortable public spaces. The designs for the project are open-source, shareable with urban planners, architects, and builders as well as policymakers and communities around the world. To Tato, the iteration of Polinature at the GSD represents a “kit of parts” that could be quickly and inexpensively mass produced.

Polinature extends Tato’s longstanding work investigating how landscape architecture can support efforts toward climate justice. With Jose Luis Vallejo, Tato is a founding member of Ecosistema Urbano, a group of architects and urban designers with offices in Madrid, Florida, and Massachusetts. Polinature refines and develops concepts at the heart of their Eco-Boulevard project for Madrid (2004–2008), described as an “urban recycling operation.” Tiers of trees arranged on a cylindrical tower provide both cooling through evapotranspiration and an inviting social space. While Eco-Boulevard became a permanent fixture in Madrid, Polinature is about providing immediate impact with zero waste. Tato designed it as what she calls a “plug-in” structure, easy to erect and dismantle in any context. That terminology evokes the work of avant-garde collective Archigram, whose members envisioned cities comprising flexible, mobile, high-tech structures that could respond to inhabitants’ changing needs.

While Archigram’s work channels the consumerist tendencies of postwar mass culture, Polinature is wholly sustainable and community oriented. When the tower comes down in mid-September, Tato and her team will give away all the plants that ring the structure to people in Cambridge. In that way, this temporary garden could have a long-term effect on the city’s urban ecology. Polinature will live on in other ways as well, especially as a learning and teaching opportunity about how we must contend with a changing climate. “The goal is that we pollinate Cambridge with the idea of the project,” says Tato.