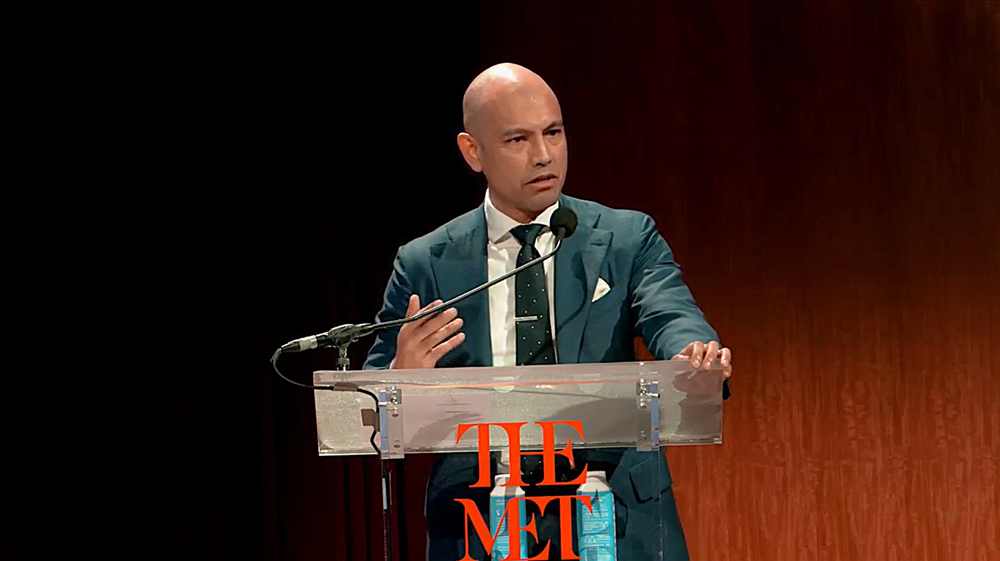

Nearly twenty years after his graduation, Jhaelen Hernandez-Eli (MArch ’06) will return to the GSD this spring to teach a seminar titled “The Art Museum: Typological Trajectories.” Hernandez-Eli is uniquely qualified to address this topic; as vice president of capital projects at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, he oversees the institution’s $2 billion construction and renovation campaign, which includes the new Tang Wing for modern and contemporary art by Frida Escobedo (MDes ’12). Beyond his course-related expertise, Hernandez-Eli will share additional lessons about his work and the opportunities for owners to support the profession. “What I would love for students to understand is, that while I don’t practice architecture in the traditional way, the advocacy is still of utmost importance. There’s real opportunity for impact.” Rather than design buildings, Hernandez-Eli crafts processes that enable “an appropriate, robust, and rigorous architecture to emerge.”

Hernandez-Eli first arrived at the GSD in 2002, after earning a bachelor of arts in architecture from the College of Environmental Design (CED) at the University of California, Berkeley. The CED afforded him an understanding of architecture grounded in site and program, informed by environmental and social concerns. At the GSD, Hernandez-Eli encountered a different approach to architecture. In first-semester core studio, Scott Cohen (MArch ’85) assigned the “Hidden Room” exercise, a problem that mandates a covert fifth room be somehow obscured within four rooms. Hernandez-Eli found this exercise enlightening, as it exposed him “to the ideas of innovating within constraints beyond site and program and, more radically, of embracing those constraints.”

Over the next three years, a range of faculty—including Nader Tehrani (MAUD ’91), Monica Ponce de León (MAUD ’91), and Toshiko Mori—instilled in Hernandez-Eli additional foundational principles that, two decades later, continue to shape his work. These notions include an appreciation for architecture as interdisciplinary and socially embedded, not separate from the society that constructs it. Hernandez-Eli likewise developed a reverence for architecture and for the architects and craftspeople that make it. And he learned that, if properly positioned, he can design alternative processes within which architecture is produced, thereby bolstering architects, the power of architecture, and society at large.

The idea of designing processes has been instrumental in terms of Hernandez-Eli’s professional trajectory. While not practicing architecture in the traditional sense, he has constructed an impactful role for himself as an advocate for architecture. This began with his time at Diller Scofidio + Renfro, from 2008 through 2017, where he rose to an associate principal managing the studio’s operations and strategy, facilitating cultural projects such as the Museum of Modern Art expansion and the High Line. Hernandez-Eli then shifted from the service-provider to client/owner side, joining the New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC) as senior vice president, head of design and construction, where he spearheaded projects fostering social and economic equity, including public food markets and the city’s waterfront infrastructure. In 2020, after three years at NYCEDC, Hernandez-Eli moved to The Met where he oversees the design, architecture, and construction of the institution’s galleries, infrastructure, workspaces, and public areas.

At The Met, Hernandez-Eli has guided multiple projects such as the renovations of the Rockefeller Wing (by Kulapat Yantrasast of WHY Architecture) and the galleries for Ancient Near Eastern and Cypriot Art (by Tehrani of NADAAA). He also continues the larger undertaking he initiated with the NYCEDC: using his institutional role to demonstrate the opportunity owners have “to be bold, bringing in new voices and tackling the pressing issues of our time.” Most owners, he explains, approach the commissioning process in a risk-averse manner, choosing established firms with a well-stocked portfolio. Yet, Hernandez -Eli asserts, “if you know how to manage the project and build an infrastructure behind the scenes to mitigate such risks”—for example, pairing a younger architect with an experienced firm—owners can level the playing field for new voices. And while one might argue that customary design competitions offer newcomers a point of entry, Hernandez-Eli would vigorously disagree. “Competitions are terrible!” he declares. “Architects are undervalued and underpaid through that process. It also does not put the client in the best position to make the right decision.”

To illustrate how owners can design a process that supports less established architects, Hernandez-Eli references the example of Escobedo. As the New York Times noted upon her selection in 2022, “Escobedo, 42, is a surprising choice for such a major assignment given that she is relatively young, has mostly designed temporary structures, and is not a household name.” While these attributes might be deterrents for some, not for The Met. To settle on an architect for the Tang Wing, the museum adopted a workshop model, inviting a shortlist of relative newcomers to participate. Hernandez-Eli and others worked with the architects individually over the course of six months, meeting every two weeks, “getting to know them, guiding the process, helping them understand the constraints—just like the Hidden Room project.” In the end they chose Escobedo, stating in a press release that “her work draws from multiple cultural narratives, values, local resources, and addresses the urgent socioeconomic inequities and environmental crises that define our time.”

Alongside supporting newer architects, another opportunity for owners involves socioeconomic and environmental impact. For Hernandez-Eli, “design coordinates labor and materials around a set of values and manifests those values.” He continues, “engaging with architects who demonstrate a commitment to craft and artisanship, we’re looking to proactively curate the dollars [associated with our projects] into the local economy, local craftspeople, new technologies, so that we can participate in building a robust middle class.” This translates into job creation; for example, instead of importing artisans for a project, “we might fly them in to teach artisans here, who then develop new skillsets and become resilient themselves,” Hernandez-Eli explains. “It’s about keeping things hyperlocal, not shipping your granite in from Italy, but sourcing materials from within, say, a 50-mile radius,” thereby supporting regional suppliers and reducing the project’s carbon footprint. Hernandez-Eli’s larger message for owners? “Designers can’t maximize their impact alone. It is the responsibility of owners to set our designers up for success—embrace the work they’re doing and partner with them to choose how we spend those dollars.”

In a few months, Hernandez-Eli will help students explore the evolution of museum typology. Simultaneously, he will model non-conventional methods for championing architecture and architects. As Hernandez-Eli observes, “my story shows students that there are different paths to take, and there are different ways of advocating for architecture.”