One hundred thirty years ago, environmentalist and landscape architect Charles Eliot walked the Blue Hills, a vast green swath south of Boston, envisioning its transformation into a wilderness reserve. Looking out to the horizon from the hill’s peak, he saw not a wild forest but hundreds of thousands of coppices— clusters of sprouting trunks created by cutting a tree close to the ground and causing it to release what Anita Berrizbeitia calls “repressed buds” that wait beneath the bark. Walking the same hills Eliot traversed all those years ago, and in the process of researching the wilderness’ origins in archives, Berrizbeitia was surprised to find that Eliot’s Blue Hills reservation plan emerged out of an agricultural forest that provided lumber for settlers for two hundred years, and that he proposed to remove more than 400,000 coppiced trees by using grazing sheep to prevent the sprouts from developing, and then lifting the roots systems out of the ground by hand, one by one—a laborious, time-consuming process.

Her research of the Blue Hills led Berrizbeitia, professor of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), to consider what makes a forest “wild,” how all forests are culturally constructed, and how our contemporary landscape honors or erases indigenous history. These are the themes that she’s now exploring with her students in “Forests: Histories and Future Narratives,” a course that follows on the heels of Forest Futures, the exhibition she curated at the GSD last spring.

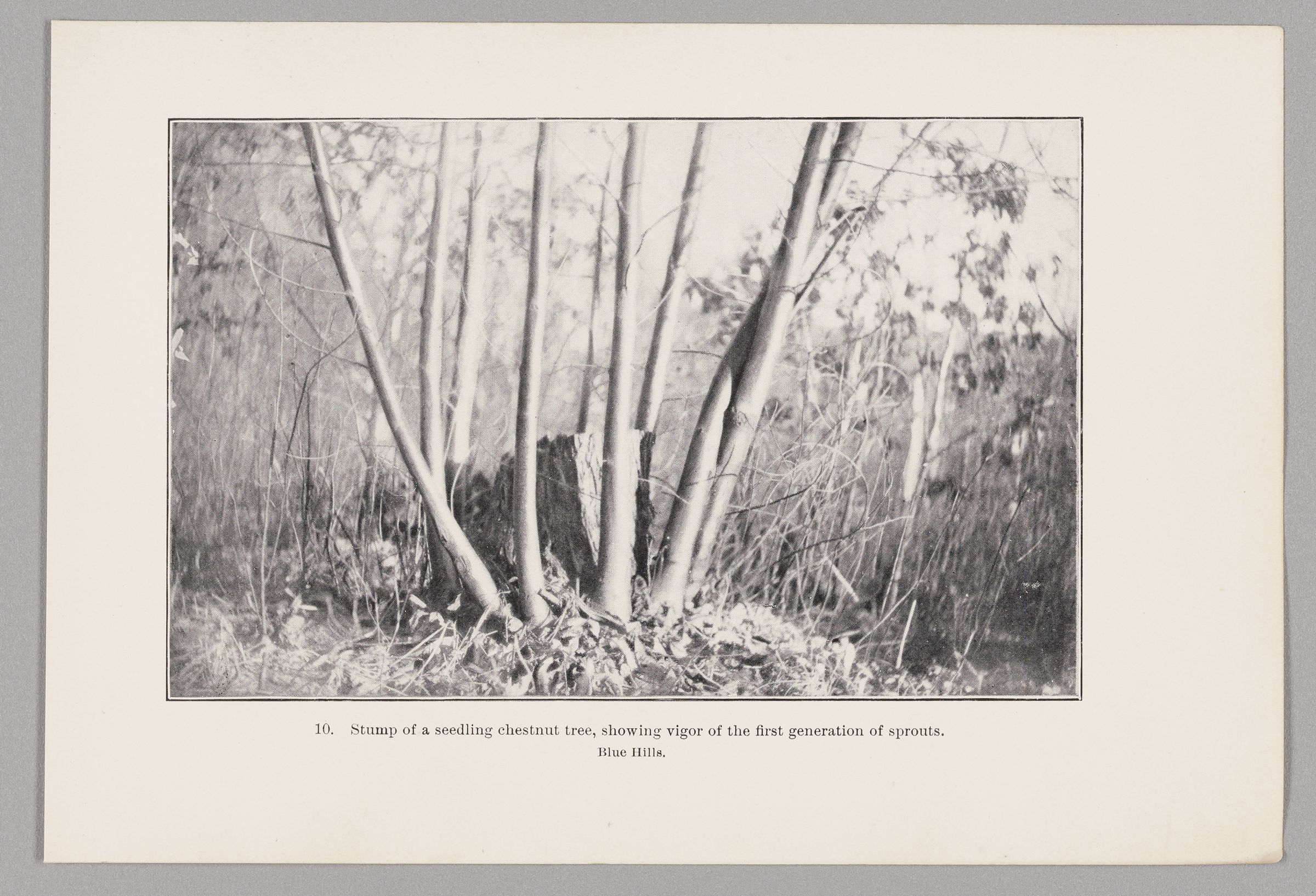

In temperate forests, write Rob Jarman and Pieter D. Kofman in Coppice Forests in Europe, “simple coppicing” can be achieved in mid-winter, when the tree is dormant. Cut the tree near the base, and then, come spring, explains Berrizbeitia, “the energy previously spent on the canopy and the leaves but now entirely contained in the root system is reassigned to dormant buds contained in the remaining stump or in the roots.” The trunk sends up “vigorous growth of straight poles within a short span of time.” The new shoots can be cut at whatever size is required for the lumber’s purpose (firewood, construction, furniture, etc.), and can be harvested over and over again for decades—even centuries—from every three to 30 years. “In a coppice system, the roots remain alive and productive for hundreds of years,” says Berrizbeitia. “Historian Oliver Rackham refers to this phenomenon as the ‘Constant Spring.’” Coppiced trees in England have survived for two thousand years and hold in their trunks valuable information about the past. Kofman and Jarman note that coppices “of all kinds and ages are of interest for their associated wildlife and for their cultural heritage.” Some plant and animal species need the “open spaces…, edge habitats and alternate light and shade conditions” that coppices, as opposed to the thick overstories tall trees, provide.

In attempting to transform an agricultural forest into a recreational one, Charles Eliot confronted questions about what makes a forest and how cultures are reflected in those landscapes.

Thousands of years before colonists arrived in New England, the Massachusett nation inhabited the region we refer to as “The Blue Hills.” In fact, “Massachusett” means “people of the Great Hills.” For 8,000 years before European contact in the 1600s, the indigenous nation farmed corn, squash, and beans; used trees for their fuel, wetus, and canoes; and, says Berrizbeitia, “walked through the valleys on their way to the Neponset River, to fish and to transport material to the shore, or to return to their fields of corn in the meadows of Quincy, or to their village on the borders of Ponkapoag bog.” They had access to wild game for meat and furs, as well as valuable mines from which, for thousands of years, they drew granite and “rhyolite, a volcanic rock with high silica content” to “make sharp tools and spears.”

When European colonists arrived in 1620, like all tribes along the east coast, the Massachusett had just suffered through a plague, and, in the decades that followed, struggled to maintain their lands in the face of the thousands of Europeans who arrived on their shores. They were removed from the Blue Hills to Ponkapoag, where, today, they write, “we continue to survive as Massachusett people because we have retained the oral tradition of storytelling just as our ancestors did.”

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, settlers clear-cut the forests, taking first the white pines, whose strong trunks made excellent sailboat masts. They turned over thousands of New England acres of rocky soil, built stone walls to mark their property, and planted crops to feed the colonies— often with the forced labor of enslaved Africans and indigenous people whose land the colonists stole.

Berrizbeitia surmises that, in the late 1800s, Eliot knew about the Epping Forest in England, where pollarded trees (created in the same way as coppices, but cut higher up their trunks) had been harvested for centuries and inspired a debate among residents and experts: Should the coppiced trees remain or be removed? What should this new forest look like? Designer and social activist William Morris argued that the coppices represented an important part of the cultural history of the region, and vehemently opposed biologist Alfred Russell Wallace’s proposal to import trees from other nations (including the US and China) to help diversify the English forest. This first attempt to apply biogeographic diversity to design was rejected, and the pollarded trees remained. They can be found there today, in tall clusters, evidence of the forest’s history.

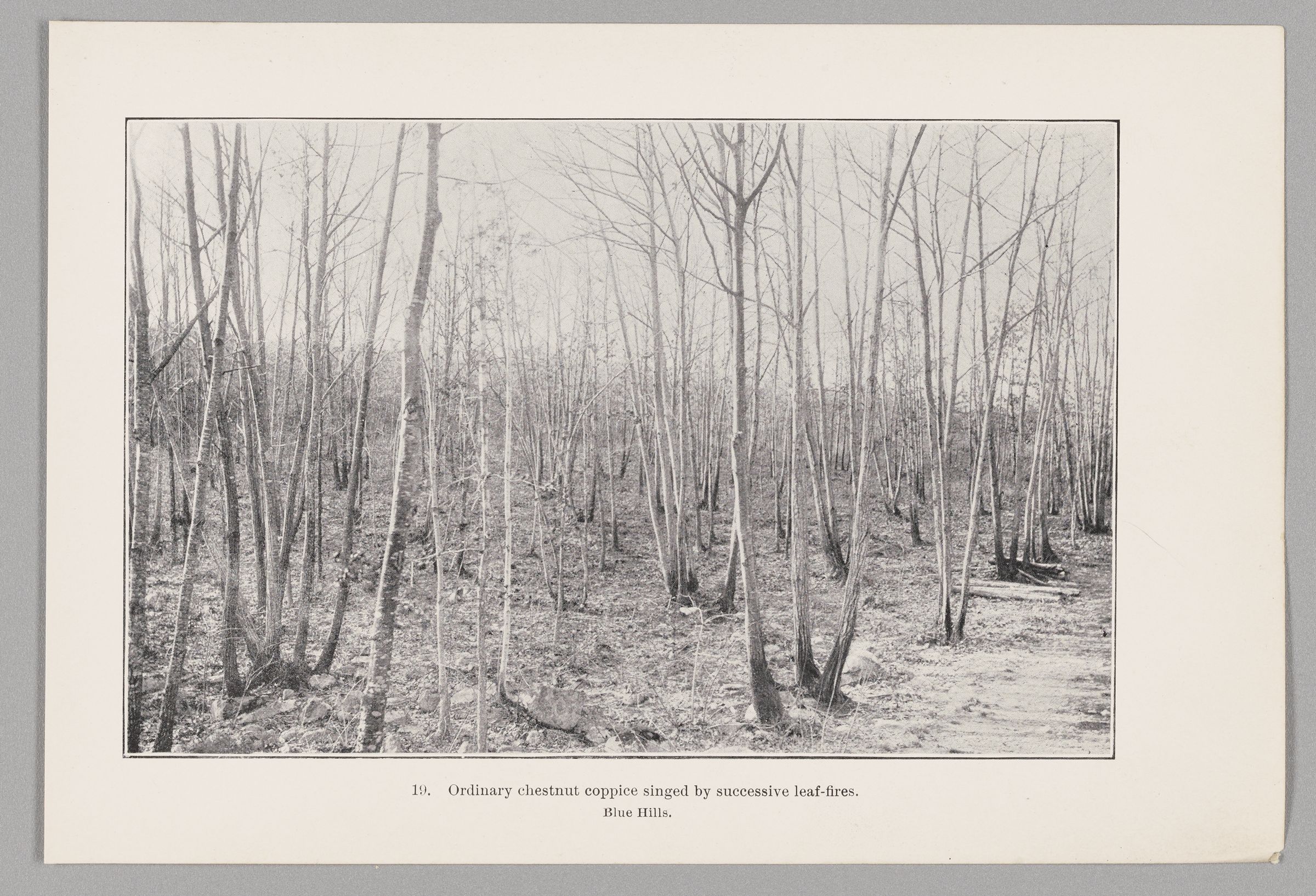

In the Blue Hills, says Berrizbeitia, Eliot noticed seedlings growing between the coppices. He knew that, if left to its own devices, the forest would regenerate. He was right—but, frequent forest fires prevented the natural regeneration of the forest.

The Massachusetts government decided they had to intervene. “They realized, ‘we devastated our soils with agriculture.’ What’s going to happen to us?” To jumpstart a new succession cycle, as the regeneration process is called, they planted white pines in large numbers, adding over one and a half million in the Blue Hills. This is a practice the US forest service continues today, planting pines and other trees throughout the US, an aspect of silviculture—a word coined in the late nineteenth century, when Eliot was hard at work on the park system.

All along the outskirts of Boston, the lands Eliot developed into the Metropolitan Park system were full of coppiced forests, the primary source of fuel in the area until the transition to coal took place in the 1880s. Instead of remnant wilderness, these were fallowlands, abandoned forests that needed to be put to a different use. He likely began his project to remove the coppiced trees, Berrizbeitia theorizes, but soon enough, the gypsy moth and chestnut blight took hold in the area, killing the coppiced trees. Thousands of new trees—a variety of species—were brought in from nearby nurseries, and when those failed, more were planted. Berrizbeitia is now researching the infrastructure that drove the transformation of the Blue Hills—including where those millions of pine seedlings were cultivated, and how they were transported and stored.

She argues that Eliot’s proposal to remove the coppiced trees was an attempt to erase the imprint of settler’s colonization of the Massachusett people’s land, and that although he knew the importance of the hills to the indigenous nation, he did nothing to recognize them beyond the naming of landmarks.

In the face of the current environmental crisis that requires a transition from fossil fuels to renewable and diverse energy sources, coppicing has reentered the conversation on sustainable resources. Combined with other energy sources, such as solar and wind power, says Berrizbeitia, it’s possible that harvesting lumber with coppicing techniques could become another energy resource. Although still widely used in Europe, coppicing is now experiencing a revival in the US. Berrizbeitia’s research on the Blue Hills restores to the region the story of a designed forest whose history might help us move into an uncertain future with more tools at hand.