For his first architectural commission, Peter Chermayeff landed a big fish: Boston’s New England Aquarium. It was 1962; Chermayeff was 26 years old, had earned his master of architecture degree from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) a mere six months prior, and didn’t yet have a license to practice architecture. He and his partners had just created Cambridge Seven Associates, a multidisciplinary collaborative firm of architects and graphic designers that would soon gain international prominence for a range of work, from small exhibitions to large mixed-use complexes.

More than six decades later, speaking about his early success, Chermayeff humbly observes: “I have a certain willingness to take risks, I suppose. And I have surrounded myself with first-rate collaborators.” Of course, his continued achievement stems from more than a penchant for risk-taking and multidisciplinary collaboration. A world-renowned authority on aquariums, responsible for high-profile projects such as the National Aquarium (1981) in Baltimore and the Oceanarium (1998) in Lisbon. Yet, the self-described “ambivalent architect” nearly didn’t become an architect at all. He had settled on filmmaking when a well-timed risk and a collaborative enterprise changed his mind.

The son of Russian-born modern architect Serge Chermayeff, Peter immigrated with his family to the United States from England in 1940 at the age of four. He and his brother Ivan (four years Peter’s senior) spent the next year with family friends—Walter and Ise Gropius in Lincoln, Massachusetts—while their parents traversed the country in search of an American outpost. Over the following decade and a half, as the father assumed a series of teaching positions (including stints in California, New York, and Chicago), the sons graduated in succession from Philips Academy at Andover. In 1953, the same year that Serge assumed leadership of GSD’s first-year program, Peter entered Harvard College with his sights trained on architecture. He majored in Architectural Sciences, which allowed him to commence graduate work after only three years of collegiate studies. Thus, in the fall of 1956, Peter entered the GSD.

Chermayeff immensely enjoyed his first and fourth years of his architectural studies, taught respectively by his father (“a hell of a good teacher”) and Dean Josep Lluís Sert (“a master and superb teacher.”) “The school was filled with energy and talent,” Chermayeff recalls. “I was intrigued by the power of the community, the quality of my classmates, and the fun we had in exchanging ideas. I was learning as much from my fellow students as I was from the faculty.”

Yet, even while enjoying his time at the GSD, Chermayeff wasn’t convinced that an architectural career was right for him. He had spent a summer in New York working for his brother Ivan, who had recently launched a graphic design firm with Tom Geismar. (Over the years, Chermayeff & Geismar would craft a plethora of highly recognizable logos including those for NBC, Mobil, PBS, and Chase Bank.) Another summer, Chermayeff worked with the Italian sculptor Costantino Nivola in his studio on Long Island as the artist created a large cast-concrete bas relief for an insurance company building in Hartford. As Chermayeff neared the end of his schooling, these endeavors prompted him to think less about architecture as a career and “more so about the visual arts, filmmaking in particular.”

During his final year at the GSD, Chermayeff had achieved unexpected success with a 15-minute experimental film. Titled Orange and Blue, the unnarrated film depicts two rubber balls, one orange and one blue, as they bounce from a bucolic wooded landscape into a junkyard strewn with the detritus of modern life. Taking a liking to the production, a film distributor paired Chermayeff’s short with Ingmar Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly as the Swedish feature toured the United States. Chermayeff found the unanticipated accolade to be “funny, ridiculous, but also wonderful.” What’s more, says Chermayeff, “I realized that, in the course of doing the film, I’d had more fun than I’d had doing anything with architecture.” So, upon graduation from the GSD, in 1962, a year when US officials were urging families to build fall-out shelters, Chermayeff set out to make another film—this time an informative documentary on the effects of nuclear weapons.

Six months later, as Chermayeff was immersed in raising funds and producing the documentary, his friend Paul Dietrich (MArch ’56) suggested they start a collaborative firm that would combine architecture, urban design, graphic design, and industrial design. Chermayeff declined; “Paul,” he explained, “I’m off in another direction. I’m making films.” Yet, the idea had been planted in Chermayeff’s mind.

The following week, Chermayeff made a bold move. He traveled to the Franklin Park Zoo in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood and, without an appointment, approached zoo director Walter Stone. “He must have thought I was crazy. I told him that I thought his zoo was dreadful,” Chermayeff recalls, “and that it could be rethought, reimagined, replanned, and changed for the better if he would allow us.” Stone was intrigued, agreeing to attend a slide presentation in Chermayeff’s Cambridge studio on how the as-yet-unnamed firm would revitalize his zoo. Impressed by their ideas but without funding to hire them himself, Stone introduced Chermayeff to the person in charge of developing a new aquarium in Boston. After a successful meeting, the fledgling firm was included on the project’s short list of architects, and an interview followed. Ultimately, Chermayeff and colleagues were selected to design the New England Aquarium—a lynchpin in the renewal of downtown Boston’. “And that,” says Chermayeff, “is how we started Cambridge Seven.”

As the name implies, seven partners initially comprised the collaborative venture: in addition to Chermayeff, four architects—Louis Bakanowsky (MArch ’61), Alden Christie (MArch ’61), Paul Dietrich (MArch ’56), Terry Rankine—and graphic designers Ivan Chermayeff and Tom Geismar, who simultaneously maintained their New York practice. They were all relatively young (Dietrich, in his mid-30s, was the elder stateman of the group). Yet the men had secured a major project, “an adventure in itself,” recalls Chermayeff, “because it involved reimagining and reinventing a building type—an urban aquarium, a place of encountering nature.” For Chermayeff, though, the New England Aquarium commission took on additional significance: “it meant that I could in fact find my way in this field because the project called for interwoven exhibition design and graphics and would address the content of things as much as the form of the envelope or the planning of the surroundings. It became, for me, place-making with a purpose, driven by content and context.” Opened in 1969, the Boston aquarium played a key role in transforming the city’s waterfront into a vibrant public locale. It also led to more aquarium commissions around the globe.

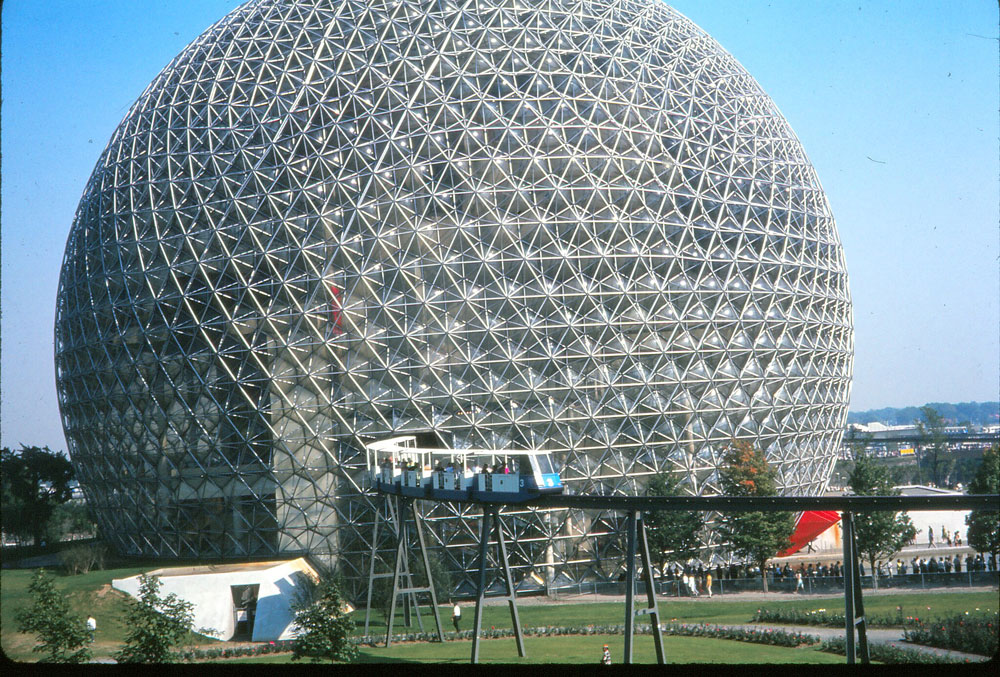

Even before the New England Aquarium’s completion, though, Cambridge Seven acquired two noteworthy projects—”not from the aquarium particularly,” Chermayeff notes, “but from the notion of the firm as a multidisciplinary collaboration.” The first arrived in 1964 when Jack Masey, design director for the United States Information Agency, invited Cambridge Seven to spearhead the US Pavilion for Expo ’67 in Montreal. Chermayeff and the others worked with Buckminster Fuller to make a transparent bubble, a geodesic dome as a three-quarter sphere 250 feet in diameter, which Fuller’s team engineered. Cambridge Seven designed the interior, which consisted of staggered platforms, described by Bakanowsky as “lily pads,” joined by escalators and stairs. Exhibits showcased items from a NASA lunar landing module and oversized works of contemporary art to Raggedy Ann dolls and mouse traps—all products of American creativity and ingenuity. An elevated monorail further animated the pavilion, bisecting the spherical space at the equator as it transported Expo visitors throughout the fairgrounds.

The other prominent multidisciplinary project Cambridge Seven tackled in the mid-1960s involved environmental design for the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) transit system. As Chermayeff notes, “We made some basic changes that had to do with the experience of the user, the people who use the system, riding the trains or the buses, walking through the stations. We developed guidelines and standards and, above all, a system of graphics and identity that unified the different subway stations and gave clarity to where you were and where you were going.” These changes included rebranding the transit system as the “T,” an idea borrowed from Stockholm, Sweden. “We concluded that the ‘T’ would work as a symbol for a lot of very good reasons. Intuitively, if you see the letter T, you can think of transportation, travel, transit, tube. . . so many words that conjure the notion of what it’s all about,” Chermayeff says. Geismar painstakingly created the black-and-white “T” logo, still ever present throughout the Boston region.

Likewise, a version of the “T”’s minimalist spider map remains in use today, coherently depicting individual locations within a larger, unified system. As Chermayeff explains, they color coded the subway lines, providing each line with a geographically derived identity. Thus, the former Harvard–Ashmont Line was renamed the Red Line, referencing Harvard’s signature color. The track running to Boston Harbor and northeast along the sea became the Blue Line, while the Green Line branched toward Olmstead’s Emerald Necklace southwest of Boston. “And Orange . . . well, I just didn’t know what else to do,” Chermayeff confesses. “It was a fourth color, and it made sense to combine with the others!”

Above ground, the colors simplified the user experience, signaling the stations’ affiliations. “As you walk down the street, if you see green and orange, you know that this station takes you to both Green and Orange Line trains. This means that the whole city, the skeleton of the city, becomes more legible,” Chermayeff notes. “Looking back on it,” he concludes with a grin, “in terms of the impact on millions of people over time, I think what we did there was pretty terrific.” That this overarching scheme for the MBTA endures today, nearly sixty years later, suggests that Chermayeff is indeed correct.

Moving into the 1970s, Cambridge Seven continued to garner attention, completing an array of work including museums, educational buildings, and mixed-use complexes, eventually winning the American Institute of Architecture’s prestigious Firm of the Year award in 1993. Chermayeff became known internationally as the foremost aquarium architect, leading significant projects throughout North America, Europe, and Asia. He also continued to make films, including the eleven-part, non-narrated Silent Safari series for Encyclopedia Brittanica that depicts rhinoceroses, lions, and other animals in their natural East African habitats. Chermayeff left Cambridge Seven in 1998 with two younger collaborators, Peter Sollogub and Bobby Poole, and he continues to practice design with Poole.

Throughout his career, Chermayeff, the “ambivalent architect,” has approached the built environment through a multidisciplinary lens, integrating design and visual culture to make useful, inviting, inspiring places for the public at large. Thinking about the profession today, he forecasts an even greater need for collaboration. “An architect is, almost by nature now, an expression of a collective will rather than an individual will,” Chermayeff asserts. “We learn from each other, and we learn by tackling and solving problems that matter. I like to think that in the next several years, we’ll find ways to address issues like housing and the environment more broadly, where instead of individualistic statements, design occurs through more bees building their bits of the hive, reinforcing each other to make urban places that are humane and rich.”