Widely known during his life as the “dean of African American architects,” J. Max Bond Jr. (AB ’55, MArch ’58) commanded respect in the field as much for designs that privileged the people who inhabited them as for his leadership fighting for racial justice in cities. Earlier this year, the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) renamed the largest classroom in the school’s Gund Hall in honor of the prominent alumnus, whose work includes the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta, the Harvard Club of New York, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York.

Members of Bond’s family, Harvard classmates, former business associates, and those invested in his legacy gathered last week in Piper Auditorium, steps away from the J. Max Bond Jr. Room, to celebrate his life and work. The gathering was equally an opportunity to confront the truth that Bond’s many accomplishments in the field of design came despite the racism he faced in his chosen profession as well as at Harvard. While intended to honor Bond as an “architect and urban activist,” Sarah M. Whiting, Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture at the GSD, made clear in her introductory remarks that the classroom renaming was also about reckoning with the “extreme ugliness” of Bond’s time at Harvard, “making sure the community remembers both.”

The event centered on a lecture by Brian D. Goldstein (AB ’04, AM ’09, PhD ’13), a historian of architecture and urbanism at Swarthmore College whose forthcoming book on Bond grounds his work in broader currents of design and social justice movements in the second half of the twentieth century. (A recording of the talk and subsequent panel is available online.)

Bond attended Harvard College and then the GSD at a time when racial discrimination was rampant even while the institutions promoted liberal values. As Goldstein eloquently recounted of Bond’s time at the GSD, for example, Bond undertook a course of study shaped by Dean Josep Lluís Sert that emphasized modes of modernist design rooted in egalitarian social commitments and humanistic intentions. Yet, the aspiring architect’s experiences at the school and life in Cambridge often contradicted these ideals. This “place of possibility,” as Goldstein called Harvard, was also a site of “discouragement and violence unlike anything Bond had experienced in the Deep South.”

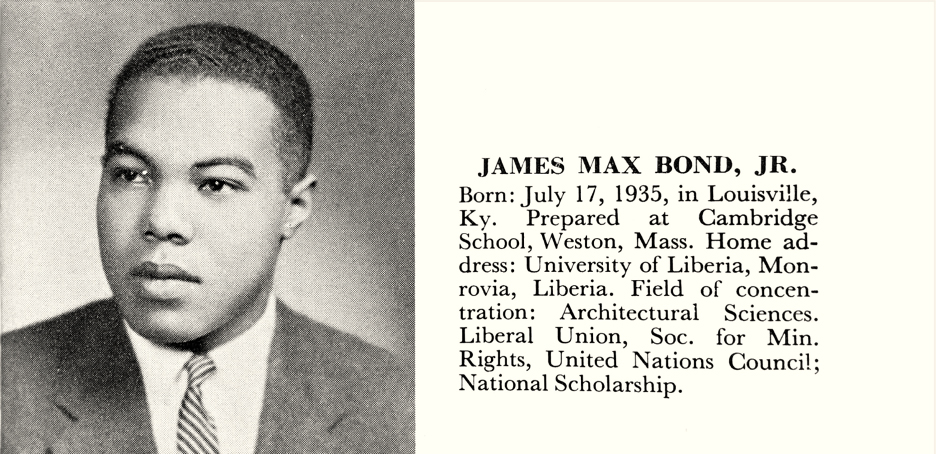

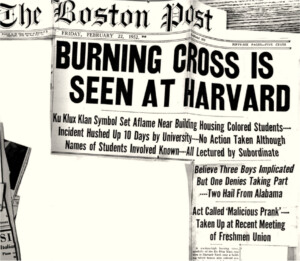

Entering the College in 1951 at the age of 16 while his family lived in Monrovia, Liberia, Bond was among 15 Black students in his freshman class. Arnold Howe (AB ’55), the only living graduate of this pioneering cohort, was in attendance at the event. The challenge of settling into the university environment at such a young age was intensified for Bond by the antagonism of classmates and instructors alike. One especially horrifying incident occurred outside the freshman’s dormitory on Harvard Yard; as Goldstein put it, “the iconic built environment [became] an instrument in the project of racial terror.” One night, several Harvard students set a cross on fire in front of Stoughton Hall, the dormitory where the majority of the Black students in the class lived at the time in an “effectively segregated space.” Active in civil rights organizations on campus, Bond refused to dismiss the attack as a mere “prank.” He co-authored a letter to the editor in the Harvard Crimson decrying racism on campus, and the story was eventually picked up in Boston newspapers and other publications around the country.

Bond spent his undergraduate years majoring in architectural sciences, an academic track that allowed him to spend his undergraduate senior year at the GSD. Speaking on the panel, Moe Feingold (AB ’54, MArch ’58) recalled Bond’s quiet studiousness within the program as well as his willingness to take risks, for example designing a kindergarten classroom with open fireplaces to gather around. Like any student, Bond faced struggles in the academic environment as well. Yet the already rigorous course of work was made more harrowing by open discrimination. One professor, Goldstein explained, pulled Bond aside to let him know that a Black man could not succeed as an architect and to admonish him to pursue a different profession. Goldstein cited census figures from the time that count only 180 Black architects in the United States compared to more than 23,000 white people in the field.

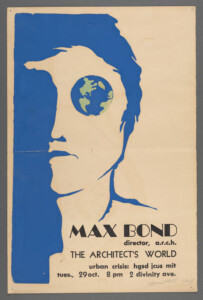

Bond earned his degree and only rarely returned to the university, though he did come back to Cambridge in 1968 to lecture in his capacity as executive director of the Architects’ Renewal Committee in Harlem (ARCH), an organization dedicated to community-driven renewal efforts. This initiative stood in contrast to the dominant strains of urban design that Bond encountered at the GSD, which often seemed blind to the racial disparities in the top-down “renewal” projects that led to mass displacement of Black residents in particular.

Several of the speakers noted that, as an architect, Bond focused first on how inhabitants would experience the spaces he created. David Lee (MAUD ’71), a colleague of Bond’s, observed that “architecture for him was about the people rather than the form,” and that he “found form that reflected the condition and the people that he was working with.” Illustrating this approach, a selection of photographs from the J. Max Bond Jr. Papers at Columbia’s Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library has been installed in the classroom. These images, many likely taken by Bond himself, depict his buildings filled with people, emphasizing the everyday use of space.

Through Goldstein’s presentation and the subsequent discussion, a portrait of Bond as a person emerged. Steven Davis, a former partner of Bond’s at Davis Brody Bond, described how Bond’s intense work life was balanced by a “wicked sense of humor” and concerns for the prospects of other Black architects until the end of his life. “You mention Max’s name and you pause for a moment,” said Lee, “He had that kind of presence.” Indeed, many of the people who knew Bond personally have supported efforts to continue his legacy. Isabel Strauss (AB ’13, MArch ’21), an incoming faculty member at Smith College, and Shawn L. Rickenbacker, director of the CCNY J. Max Bond Center for Urban Futures, spoke about the ways they have attempted to create resources for design students today to understand Bond’s work and create initiatives in urban design that are true to his vision.

Bond was a skeptic about institutions, as Goldstein noted, yet the spirit of his work can also continue in settings that now carry his name. Bond’s name, as Dean Whiting argued, will be a constant reminder for the community of its fraught past and potential futures. In that sense, the renaming is not a capstone on the experiences Bond had at Harvard, but the start of ongoing work to remember and repair.