For the last 30 years, motorists in Norway have driven winding roads into the mountains and fjords along the country’s 18 National Scenic Routes, many of which skirt stunning coastlines, and are home to Arctic foxes, whales, and reindeer. Norway began developing these routes in the 1990s, by competitively selecting architects to design viewpoints and rest areas in the often fragile terrain. Now, with tourists flocking to witness the views—as well as the internationally renowned toilets, rest stops, viewing platforms, and other service facilities—and escape the quickly warming Mediterranean, the government faces the challenge of managing traffic along the narrow, winding roads, many of which, explains Luis Callejas, visiting professor in landscape architecture at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), were first traced in the eighteenth century for their views rather than efficiency.

In 2022, LCLA OFFICE, the firm Callejas directs together with Swedish-Norwegian architect Charlotte Hansson, was selected from an applicant pool of 81 design teams to develop sites on the Scenic Routes for the next six years. The beach where they’ll design a rest stop and bathroom is on the Lofoten Route, an archipelago above the Arctic Circle. With craggy, snow-topped peaks and shimmering teal-blue water, it remains in almost complete darkness all winter, except for frequent northern lights that draw visitors, and then becomes resplendent in 24-hour summer sunshine, a “paradise for arctic surfers, with fjords as the backdrop,” Callejas explained.

As part of his studio this spring, “Landscapes of the Norwegian Scenic Routes,” he traveled with GSD students throughout southern Norway, exploring some of the most important architectural designs along several routes with diverse landscapes, from wide sandy beaches to snowy fjords. Students have spent the semester creating their own speculative interventions, which Callejas says would need to endure under changing environmental conditions.

“One of the key questions of the studio,” he explained, “is how climate change and climate policies will affect the projects of the Scenic Routes.”

Callejas asked students to consider how their designs might marry environmental savvy with the durability the road conditions demand. And, because small communities along the Scenic Routes are impacted by tourists who arrive en masse each season, students’ sites must also lighten tourists’ impact—for example, limiting where they walk and directing how they spend their time during a rest stop—while allowing them to experience landscapes that are both magnificent and fragile. The paradox of the country, Callejas noted, is that it has “very sophisticated climate policies in terms of pollution and the standards in which infrastructures can be built,” but because it’s also geographically complex, it’s not connected by rail as are other European countries. Thus, rest stops need to include fill stations for today’s gas and electric cars, with the ability to be adapted for the near-future when all cars are electric.

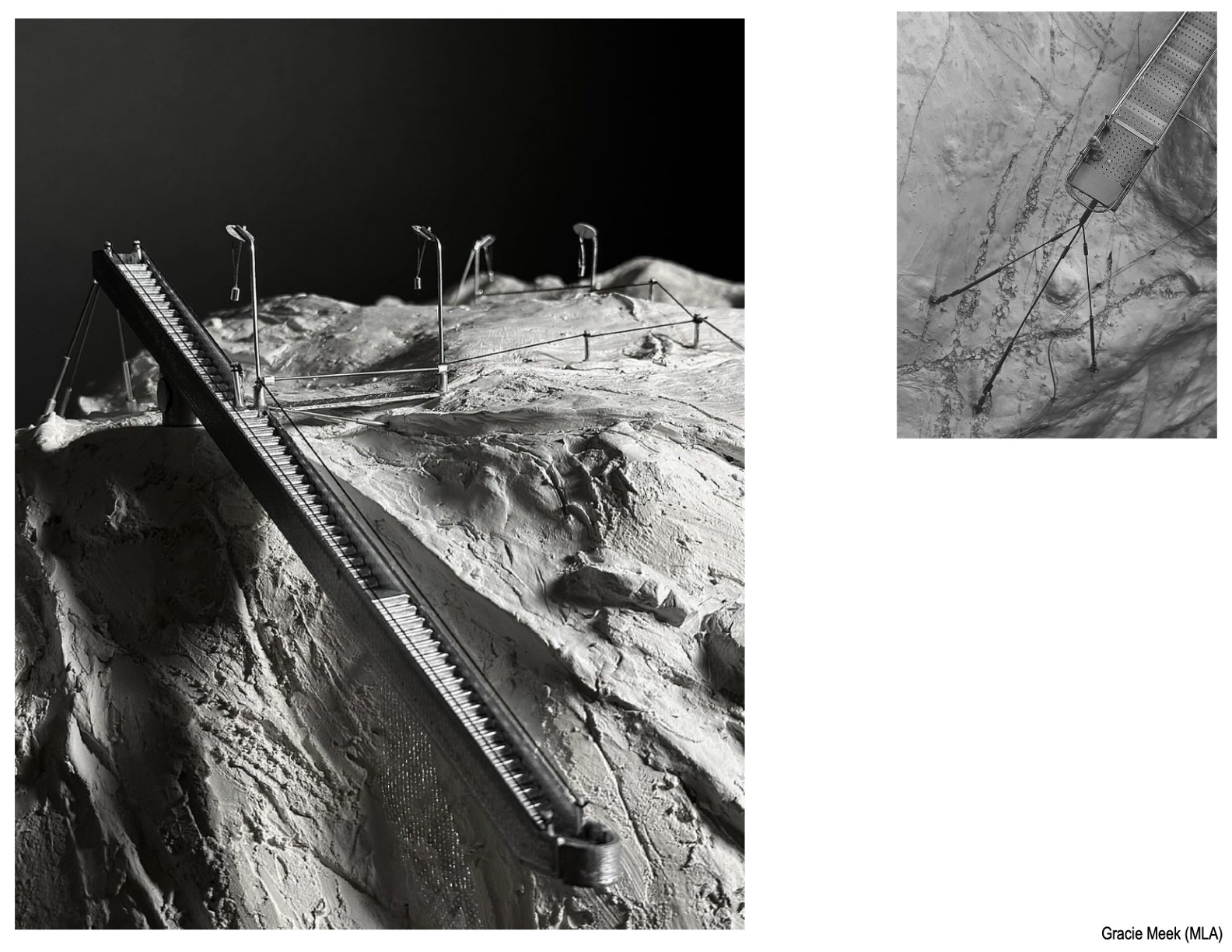

The scenic routes are sections of roadways that were cleared hundreds of years ago, meandering through the country’s most beautiful landscapes, with narrow stretches etched into rocky fjords. Water constantly moves across the rock and roads, which can trigger disasters such as avalanches and floods. “Students learn that this is a design opportunity,” Callejas said, “as opposed to an engineering problem.” Additionally, the public is very sensitive to any visible interventions in the natural world, and will only accept well-designed solutions. This problem-solving, he says, is one of the elements of the studio that he most enjoys.

Students were tasked with designing three projects, the first without ever having visited Norway, a feat made possible thanks to what Callejas calls Norway’s “digital twin.” The country’s publicly accessible surveys map the land down to 20 points per square meter. He asks his students to consider “what happens when the digital twin is so high resolution that it starts to challenge the idea of direct experience as something that is always necessary?” Drawing a comparison to medicine, in which diagnoses can be made with scans and imaging, he argues that students can use sophisticated technologies to design from afar: “I’m interested to see what happens when the students suddenly come up with attitudes towards the landscape that the locals, who know the landscape very well, may not find as easily.”

Norway’s sophisticated roadway technology also includes an app with live cameras and a range of maps and alerts on road conditions and obstacles, from avalanches to animal crossings, facilitating travel along remote routes that change rapidly in the winter. Callejas’ studio required the app’s constant and updated road condition information to move through southern Norway this February, traveling about 1,500 miles from Oslo to Geilo, southwest to Stavanger, and back to Oslo.

Along the way, they stopped at the Allmannajuvet zinc mines, which were operational in the late 1800s and reinvented by Peter Zumthor & Partner as a café and gallery, with an available guided tour of the mine. They took in the impressive Vøringfossen, designed by Hølmebakk Øymo, and visited the whimsical “fairytale toilet” at Tryvefjora, designed by Helen & Hard, where a series of pine trunks support a concrete rooftop. This is one of many celebrated bathrooms that have attracted curious tourists along the scenic routes; at Stegastein, visitors can use a bathroom that juts out over a precipice.

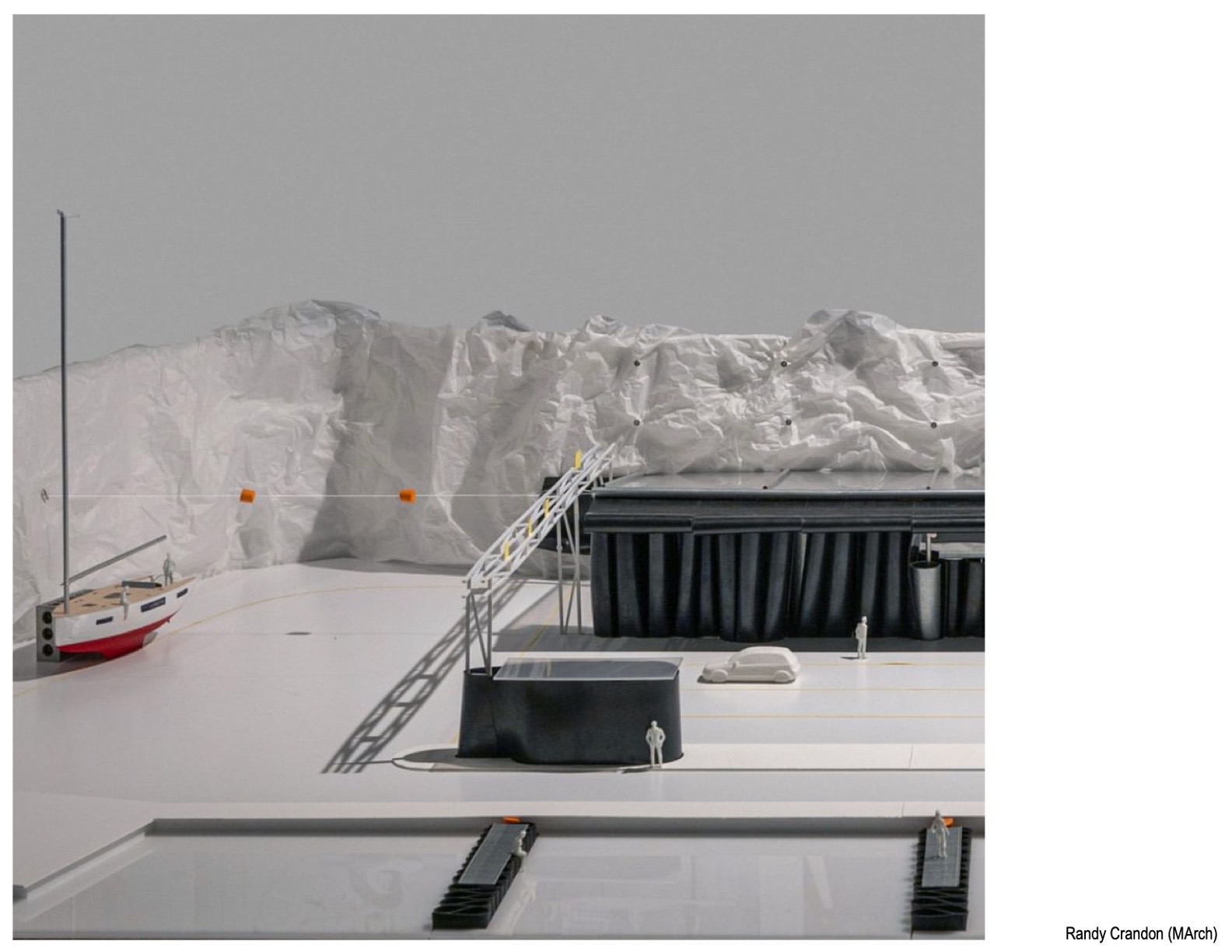

With many projects on the routes relying on concrete and steel for durability, Callejas encouraged students to build without the “heavy handedness of the infrastructural works,” and to consider alternative materials. Students created rest stops at Jossingfjord, a site well known to Callejas as his team had already proposed a rest area there. The port is unique for its “landscape defined by the presence of ilmenite, a rock type similar to the composition of the moon,” he said, and “the raw matter for titanium dioxide.” It’s been mined from this area in Norway for nearly a century.

For his part, Callejas is at work on the Lofoten beach rest area. With so many visitors arriving by car and van year-round, the roadway commission has asked Callejas’ firm to design a new public bathroom, which will need to be durable in the face of the beach’s “beautiful white sand” that will pummel it all year long. LCLA OFFICE will also design a space for “wind protection and perhaps even overnight shelter,” with access to a potable water source.

The building will be constructed of raw aluminum by local ship builders, as the area doesn’t have a traditional construction work force. Treated with a “sandblast gradient” to make the aluminum appear weather-worn, the structure will be reminiscent of the silos that still stand from the region’s industrial days. Today, at Lofoten beach, travelers might spot otters, puffins, cormorants, and dolphins—just some of the wildlife protected by Norway and accessible along age-old roads that now boast some of the region’s most interesting contemporary architecture.