A 7-mile underwater sculpture park and hybrid reef will soon trace the shore of Miami Beach. Known as the ReefLine, this first-of-its-kind project fuses public art, science, and conservation to address threats posed by the climate crisis, in particular sea level rise and warming ocean temperatures. At the same time, the ReefLine offers an innovative model for cooperation, situating art as a catalytic force that transcends disciplines and fosters wide-spread environmental stewardship. As the project’s founder and artistic director Ximena Caminos recently asserted in a lecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), the ReefLine “forces alliances between artists, scientists, engineers, architects, and communities. . . . Through storytelling, cultural practice, and knowledge, we translate complex science into shared emotional understanding and collective responsibility.”

Charles Waldeim, John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture at the GSD and co-head of the MDes program, introduced Caminos to the GSD audience. “Beyond the importance of Ximena Caminos’s work, what’s so powerful about the ReefLine is that it is a new paradigm,” Waldheim declared, “a new category of work that hadn’t existed before at the intersection of arts, design, and environmental stewardship.”

Throughout her career as a curator, artistic director, and cultural placemaker, Caminos has used art to foster community development and raise awareness about topics she holds dear. For example, in her homeland of Argentina, Caminos worked with conceptual artist Jenny Holzer to highlight the abuses of the country’s former military government. Two decades later, she orchestrated a commentary on the climate crisis with Leandro Erlich’s Order of Importance (2019), a traffic jam of 66 full-size automobiles, sculpted from sand, in Miami Beach. More recently, she curated the art master plan for the UnderLine, a 10-mile linear park on formerly fallow land beneath Miami’s Metrorail.

“To me, everything starts and ends in the ocean,” says Caminos. It seems natural, then, that with the ReefLine, Caminos has focused her attention on the marine world. Following preliminary funding from the Knight Foundation’s Knight Arts Challenge in 2019, Miami Beach residents voted in 2021 to issue a $5 million bond for the project. This sparked years of collaboration between disciplinary experts (art, architecture, technology, science), governmental authorities (city, state, federal), and local communities—all stakeholders in the ReefLine, which Waldheim aptly described as an “audacious adventure.”

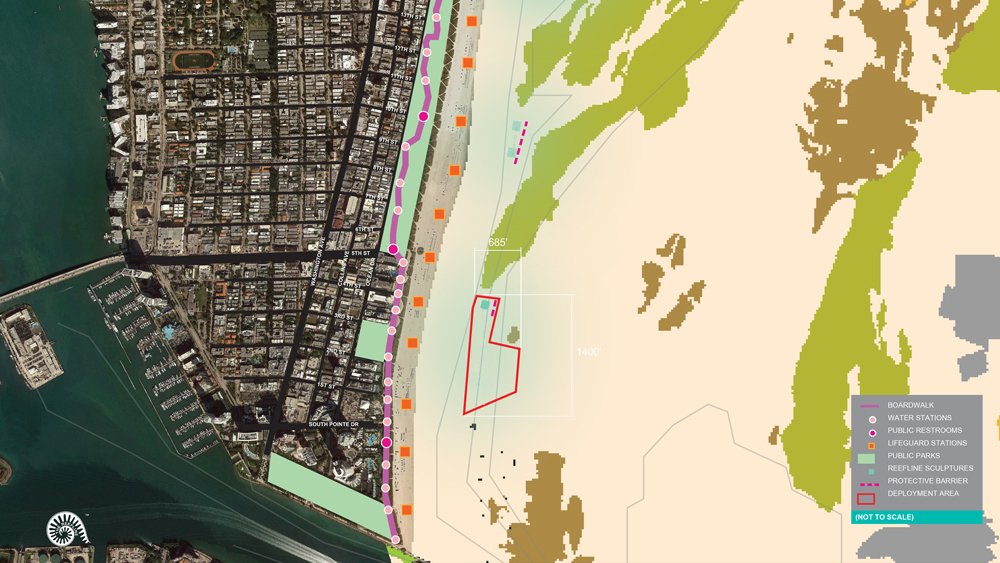

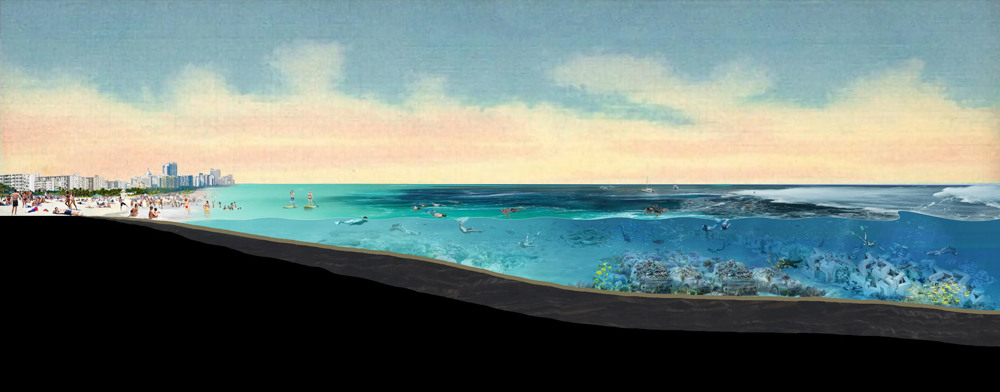

Located 600 feet offshore at a depth of 20 feet, the ReefLine begins off South Beach and runs north, featuring large-scale installations that simultaneously comprise a public sculpture park and a hybrid reef, intended to enhance biodiversity in an area ravaged by decades of sand replenishment and dredging operations. Experts estimate that, since the 1970s, 90 percent of the Florida coral reef tract has been destroyed, harming the underwater ecosystem and leaving the land even more vulnerable to rising sea levels and storm swell. Caminos and her team envision the ReefLine as providing much-needed coastline protection and, of equal importance, encouraging public interaction with—and education about—the marine environment.

The first sculpture/hybrid reef will be installed in early September. Designed by Erlich and called ConcreteCoral, the work reprises the artist’s earlier land-based installation with 22 automobiles, which have been cast in environmentally friendly concrete using 3D-printed molds. Innovative insets (Coral Loks) will attach living coral to vehicles, fostering a vibrant submerged garden for marine life to explore alongside willing snorkelers, who can simply venture out from the beach, no boat or fee required.

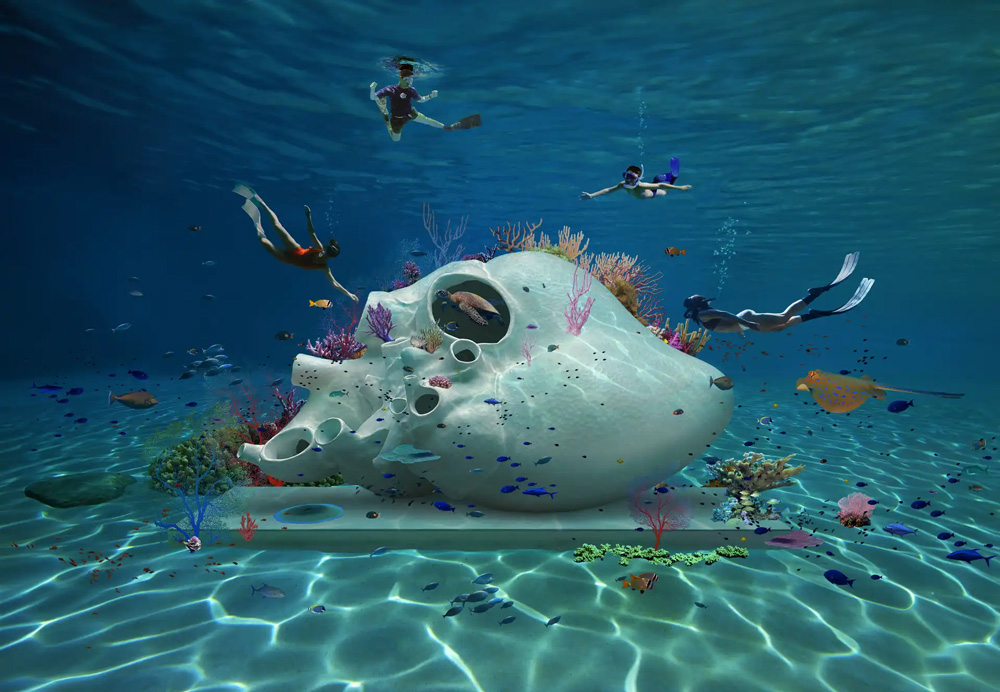

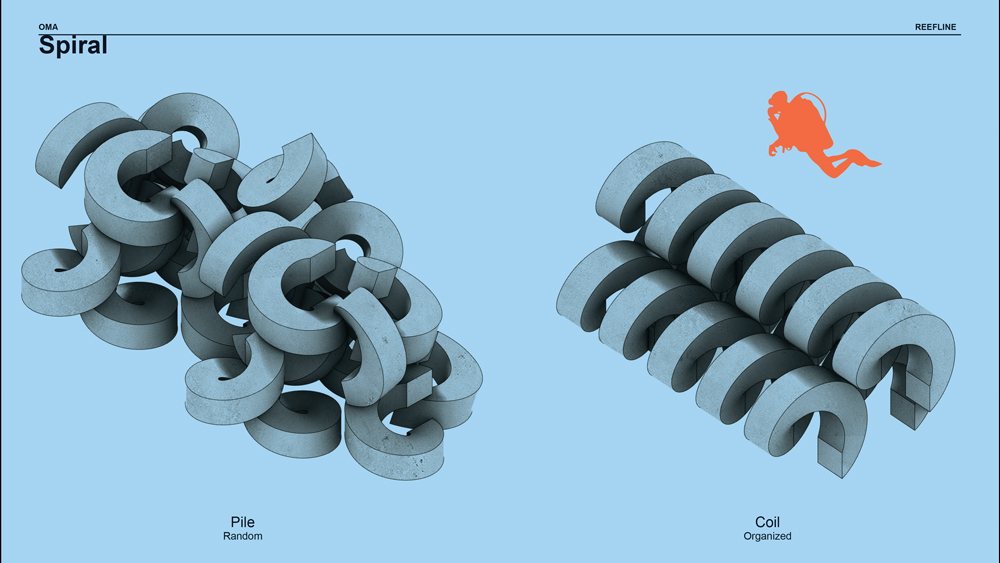

In the next two years, more sculptures will follow Concrete Coral, adding to the ReefLine’s “snorkel trail.” British artist Petroc Sesti modeled Heart of Okeanos on the heart of a blue whale and fashioned the sculpture from CarbonXinc, an experimental eco-concrete that acts as a carbon sink. Coral scientists will seed living corals in the 17-by-9-foot module, while sea creatures colonize its plentiful openings. With the Miami Reef Star, fifty-six 3D-printed concrete starfish congregate in the shape of a giant star. Designed by artist Carlos Betancourt and architect Alberto Latorre, the 90-foot-wide sculpture will be public artwork, marine habitat, and visual icon, visible via air upon approach to Miami International Airport. And a series of interlocking concrete elements—designed by OMA/Shohei Shigematsu, also responsible for the ReefLine’s master plan—will form a protective barrier against sand migration and serve as another surface on which coral may grow. Additional eco-conscious sculptures by artists from around the world, selected through a new Blue Arts Award competition, will join this collection in the future.

The ReefLine encompasses more than underwater sites, with educational components that connect the submerged installations with events on land. For example, in December 2024, the annual Art Week in Miami Beach featured a version of the Miami Reef Star arranged on the sand, as well as physical signage and digitally accessible images of the corals that will soon flourish offshore. Temporarily installed on the beach, the Miami Reef Star received more than one hundred thousand visitors throughout the festival’s seven-day run. It also drew the attention of officials organizing the 2025 United Nations Ocean Conference in Nice, France, which will now feature a twin reef star on its Mediterranean beach.

In Miami Beach, Caminos’s team has plans for the ReefLine Pavilion & Biocultural Center, situated along Ocean Drive in the popular waterfront Lummus Park. The structure, to be 3D-printed like the Miami Reef Star, will house a learning space, coral demonstrations, gift shop, and multipurpose event space. Caminos also envisions the ReefLine Salon, a regular meet-up modeled on the social salons of early modern France where individuals across disciplines will gather to informally share ideas.

Following her presentation, Caminos spoke with Pedro Alonzo, a curator, art advisor, and GSD lecturer who recently taught a course for MDes students on curation in the public realm. The discussion focused on the power of art, with Caminos commenting that “art has the power to open doors where doors don’t exist. I think that’s a hack,” she explained, and the ReefLine offers a perfect example. An incredibly complex project, the ReefLine doesn’t fall into any neat category; funding comes from a cultural grant, while a hybrid reef permit allows for its creation. Yet, Caminos emphasized that, while the ReefLine straddles art and science, art—not science—“actually unlocked the funds and the imagination of the people,” the citizens of Miami Beach who overwhelmingly support the project. “Neuroscience now confirms what artists have always known,” Caminos declared earlier in her talk; “empathy and narrative move people much faster than numbers do.”

Caminos also highlighted how the ReefLine sculptures are “doing the work and not representing it; [the art] is the environment and is serving the environment.” Alonzo echoed this sentiment. “Art tends to be symbolic, representational, and the ReefLine transcends that. Some of this work functions as a carbon sink,” he commented. “This is all very important.”

Waldheim agrees. “A mix of habitat creation, biodiversity, addressing the climate crisis directly, the ReefLine is absolutely as innovative and progressive a model for the arts and design as I’ve seen anywhere else in the world. And we are so very thrilled that Ximena came to share it here with us.”