Francis D. Pastorius’ Garden: A Botanical Cosmos in a “Howling Wilderness” (c. 1683–1719)

by Miranda Mote (MDes HPD ‘15)

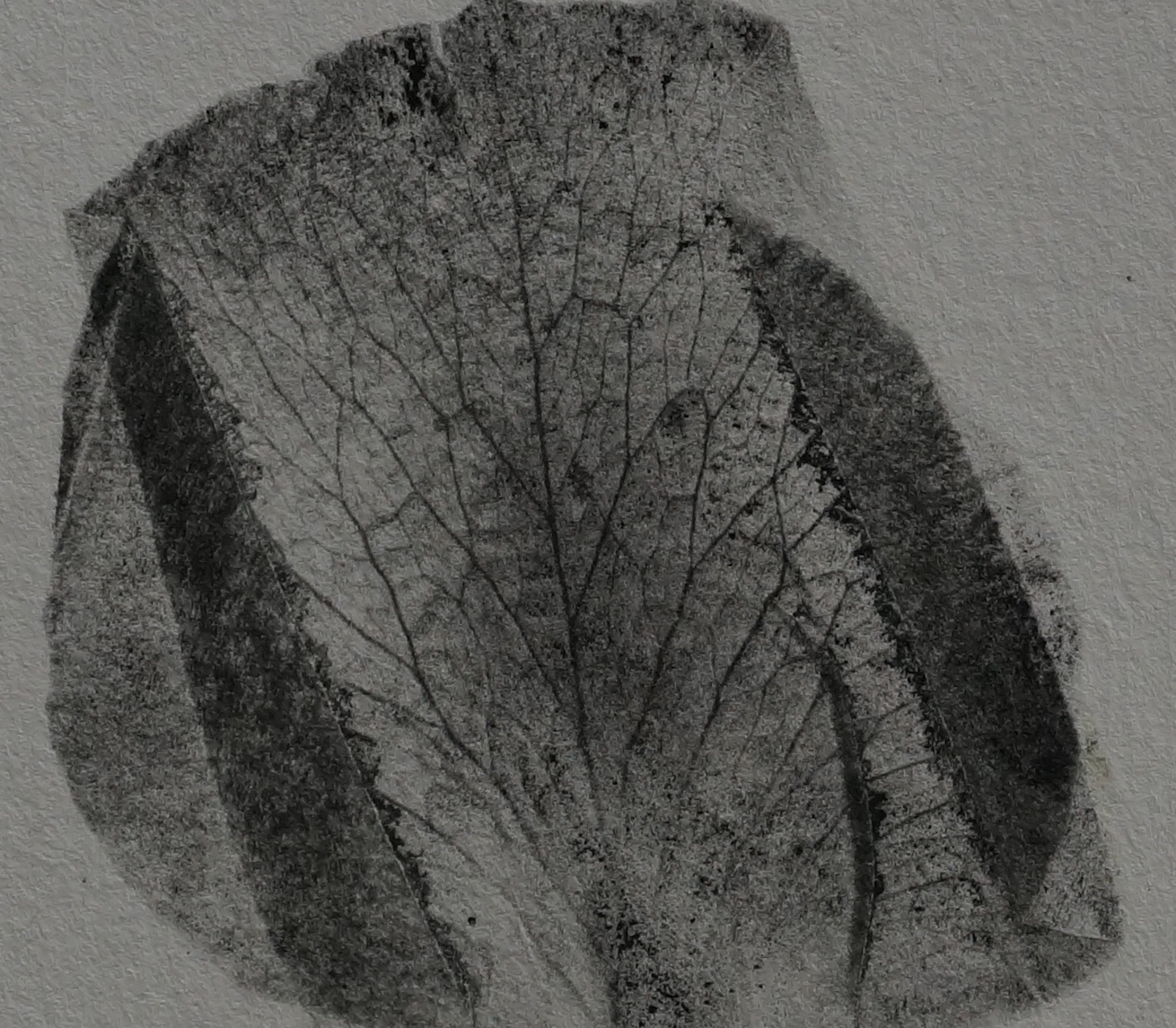

Francis D. Pastorius described Pennsylvania as Germany’s howling wilderness, a place of freedom for German Pietists. He believed all living beings had souls—including the hundreds of species of flowers, herbs, grape vines, and fruit trees that he cultivated in his six-acre Germantown garden, orchard, and vineyard. Plants bound his faith with Pietist and Quaker theologies. His Monthly Monitor briefly showing when our works ought to be done in gardens, orchards, vineyards, fields, meadows, and woods and poetry imagined a botanical cosmos as a pious animate entity in America. Through it, he contemplated and cultivated an egalitarian, alchemic existence through astrology, lunar effect, and the material of plants for the benefit of human physical and metaphysical health.

Pastorius considered his garden a woman, that measured the wisdom of his cosmos and mediated his own mortal existence in Nature. To a Pietist, a woman was a metaphor derived from the prophetic scripture of Revelations and described an androgynous spiritual ideal of divine wisdom. To Pastorius, plants were essential for human physical and spiritual health. He also understood them to be a text that decoded the divine secrets of his celestial and terrestrial cosmos. His Monthly Monitor, dated 1701, accounted for this relationship and comprehensively documented his seventeenth-century garden in eastern Pennsylvania. Most significantly, it documents how Pastorius’ formative horticultural practice and plant trade that predated John Bartram’s endeavors, was bound with practical and metaphysical purpose.

As a result of my study, I propose that “astrology,” “lunar effect,” and “vineyards” could be added to a second edition of Therese O’Malley’s Keywords in American landscape design. The zodiac and moon’s relationships to gardening, husbandry, and human health were contemplated as science in early America. They were metaphysical suppositions in the physical world of Europe that were imported through almanacs, science and garden treatises. These relationships were related to but distinct from religion and were common practice by people like Pastorius. Vineyards were central to William Penn’s vision for Pennsylvania and Pastorius’ vision for “Germanopolis.” They were also significant in subsequent generations of great American gardens and farms. All three of these keywords were formative to the cultivation and design of early American landscapes. Pastorius’ Germantown was imagined through and built of gardens, apiaries, orchards, vineyards, and fields; all of which mediated the physical and metaphysical Natures of Pennsylvania’s wilderness and Pastorius’ faith in divine wisdom.