Memory-Go-Round

by Hanna Kim (MDes ’19), Eric Moed (MDes ’19), Andrew Connor Scheinman (MDes ’19), Malinda Seu (MDes ’19)

In August 2017, thousands of torch-bearing white nationalists descended on Charlottesville, Virginia to protest the planned removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. This intensified a national reckoning with the hundreds of Confederate statues that dot cities from Jacksonville to Helena, Montana, leaving a stockpile of removed Confederate statues with nowhere to go and Americans with questions about what to do with them. Should these monuments be destroyed, or relocated to museums or cemeteries?

The violence of militant protesters in Charlottesville and elsewhere loudly echoes the Civil War. Even today, Confederate and Union continue to battle in the American public sphere, a proxy war 150 years in the making. Still, Americans on both sides have more in common than they imagine: many Confederate and Union monuments are identical, produced at the same foundry with the same likeness.

As Robert E. Lee himself wrote, it is wiser “not to keep open thesores of war but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife, to commit to oblivion the feelingsengendered.” Memorializing war heroes also memorializes war, and if the idea of a union is to be achieved without the proxy culture wars of today, monuments engendering these feelings—on either side—must be removed of their military valor. Civil War monuments must be trained for peace.

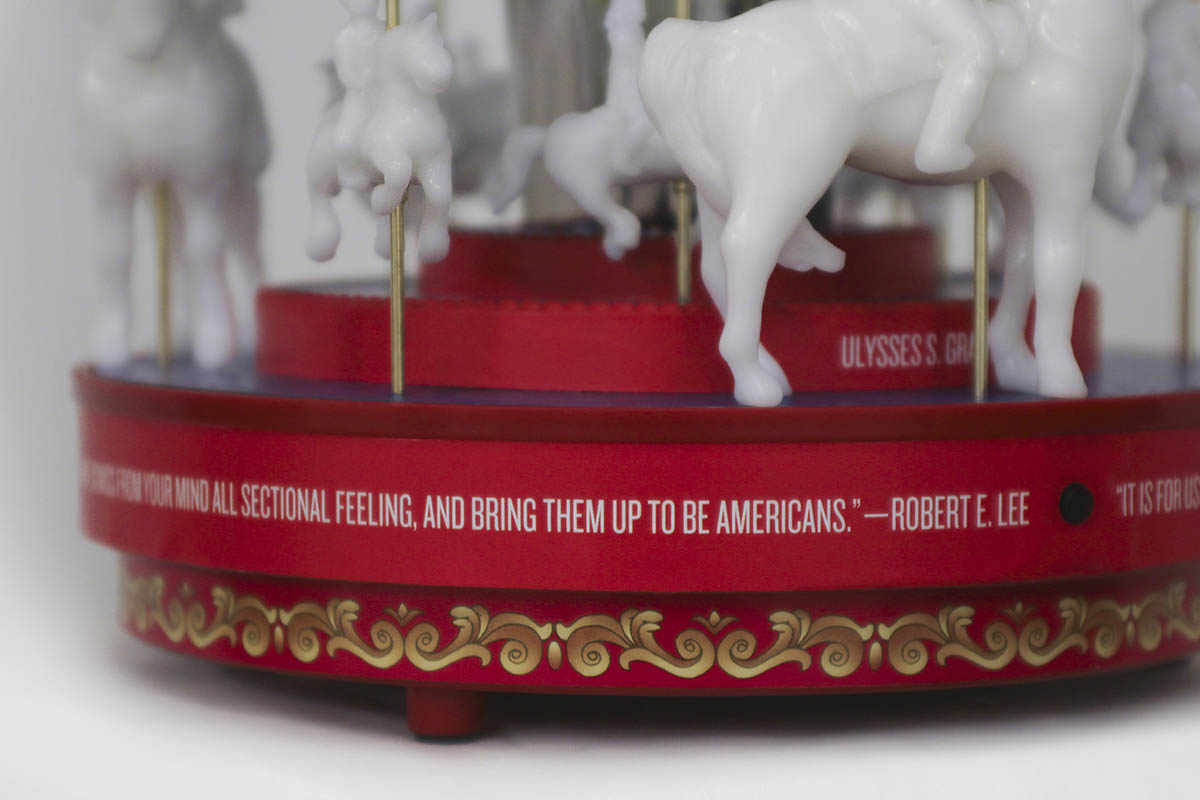

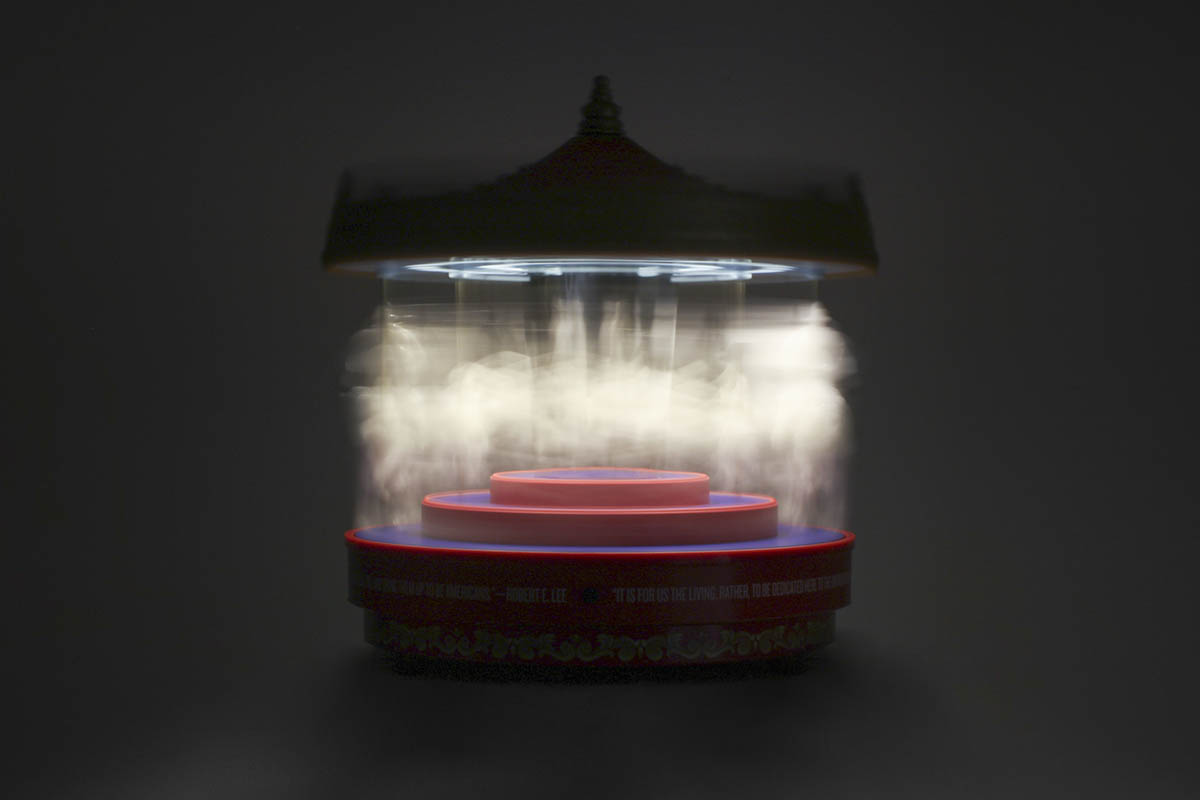

Enter the Memory-go-round, a monumental carousel that confronts Civil War revisionism by building on a different sort of American nostalgia.

Now known as a large-scale mechanical amusement ride, the carousel originated as a training game among 12th-century Arabian and Turkish warriors, named from the Spanish carosella, meaning “little battle.” In the Middle Ages, it developed into a festooned and flamboyant festival activity, for which warriors would practice on a device featuring legless wooden horses suspended from arms on a central rotating pole. Festival goers, enthralled by the public performance of these games, eventually took part, turning the carousel from a training game to an object of entertainment. Only after migrating to America near the turn of the 20th century did the carousel become the sizable, decorative ride we know today, adorned with regal ornamentation that mimics and expands upon the device’s militant past.

Civil War statues have uncertain futures and militant pasts, which must be remembered but no longer celebrated. To train them for peace, the Memory-go-round enlists these soldiers and their steeds to gallop side by side with their former enemies—to be, simply, American. Just as carousels evolved from military exercises to entertainment devices ringing in the new American century to the tune of carnival music, so too will Civil War monuments become monuments to more noble American ideals of this century—monuments to the devalorization of war, monuments toward playfulness and peace.

In its first incarnation on the National Mall, the Memory-go-round will contain several Confederate and Union monuments collected from all over the country. The Memory-go-round will travel throughout the American public sphere, inviting Americans to ride alongside Civil War veterans and atop their horses, and encouraging local monuments to join in on the fun. Cyclical and non-hierarchical, the Memory-go-round confuses North and South, refusing to take sides or even acknowledge differences between mounted Civil War generals and the children riding with them. As a monument to the removal of memorials from their pedestals, the Memory-go-round gives all Americans— Union or Confederate, past or contemporary—equal footing.