'Self-Reliant' Architecture and Body in North Korea, circa 1980

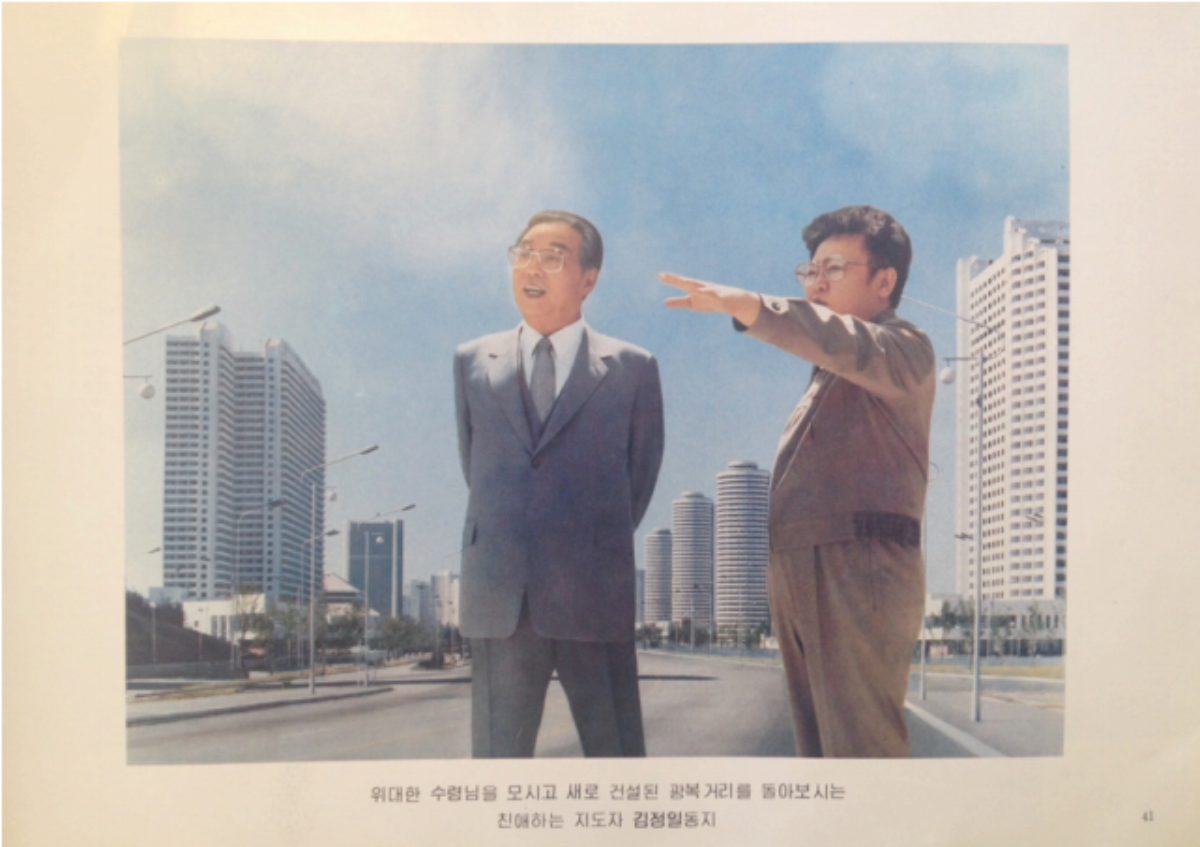

Dear Leader Kim Jong-il observing the newly constructed Kwangbok Street with his father, the Great Comrade Kim Il-sung. (Source: Dialogues on Juche Architecture, vol. 3, 41.)

by Melany Sun-Min Park (MDes ’14)

Kim Jong-il’s 46th birthday, 16 February 1987, marked the front cover of Dialogues on Juche Architecture, the first volume of a three-part tome (volumes two and three would follow in 1988 and 1990). Dialogues is the only known illustrated companion that visually coupled architectural production to juche, North Korea’s sociopolitical ideology of “self-reliance” that was made central to the mentalité of its citizens, ever since it was constituted in 1972 and reinstated in the country’s Third Seven-Year Plan (1987–1993). That discussions on “juche architecture” appeared in Kim’s treatise, On the Art of Architecture (1991), and throughout the North Korean journal, Korean Architecture (1988-), arguably cast the late 1980s and the early 1990s as a period that attempted to articulate—on architectural terms—the state’s discourse on juche.

Yet the formal translations of “juche architecture” remained incoherent: a commingling of words such as “modern” and “tradition” that found its visual and built incarnations in a motley array of structures ranging from national monuments, apartment types, to Olympic stadiums. The textual explications on “juche architecture” nevertheless converged on an elusive and broad definition that Kim had contrived: a “public-centered” architectural deliberation that was thought to belong to, and be tied to, citizenship.

Seen in this light, I ask, how it came to be that “self-reliant” architecture, which allegedly paid tribute to the nation’s own architectural heritage, expertise, absolutist patronage, and people, set the stage for the bodies that were disciplined to construct and inhabit these spaces. Indeed, how did the web of “bodily” episodes—of labor, vision, mobility, standardization, and governance—in turn reveal the paradoxes that were implicated in the idea of “self-reliance,” a kind of collective subjectivity that was ultimately managed by the Kim patriarchy?