We caught up with Abby Spinak, lecturer in urban planning and design, to discuss the courses she is leading this fall, what she hopes students will take away from them, and her design inspiration outside the classroom.

Graduate School of Design: This fall you are teaching two courses: “Critical Perspectives in Environmental Planning” and “Experimental Infrastructures.” Why are these courses relevant now?

Graduate School of Design: This fall you are teaching two courses: “Critical Perspectives in Environmental Planning” and “Experimental Infrastructures.” Why are these courses relevant now?

Abby Spinak: My courses tie Environmental Planning to recent social justice-oriented perspectives in the Environmental Humanities. Planners have known forever that society-environment relations—how we design public space, govern natural resources, define public health, and distribute access to all of the above—in practice are not so much technical optimization problems as they are contested fields in which we ultimately inscribe our values as a society in the built environment. I think the tumultuous politics of the last couple years has made this more clear than ever for the public, so now is a great time to teach students how to read human-environment interactions as politics. For example, we might explore not just the social context of debates over drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, but why and how the regulation of such activities might be hidden in a tax bill. We also talk about what to do about that as researchers and as citizens.

Last fall, I started the semester telling my students that, while “Environmental Planning” is called “environmental,” it is really a course about race, class, and power. Because we talk about the environment with words like “natural” versus “unnatural”, “native” versus “invasive”, “wild”, “urban”, “resilient,” etc., environmental planning tends to contain a lot of ideas about how we should treat each other and who belongs in what spaces. This is easier to see after you study the history of environmental planning and policy, and I hope my students will carry these lessons into practice after they graduate.

“Experimental Infrastructures” is a more focused exploration of these issues in the case of large-scale networked systems. This class asks how infrastructure inscribes social values onto the landscape in ways that subsequently constrain the ability of societies to debate and contest dominant cultural norms. You can see this in the United States in how highways and development policies in the mid-twentieth century exacerbated racial and gender inequalities, for example, or more recently in how entrenched legal and political expectations about energy, growth, and property rights steamrolled the Dakota Access Pipeline protests in 2016. What if we could start over and design a feminist infrastructure? A decolonizing infrastructure? I’ll be asking students to imagine infrastructures starting from counterhegemonic cultural values and to consider what societally would have to change to support such infrastructure, as well as how these alternative infrastructures could alter our landscapes. This is a brand-new class, so everything about it will be experimental! I’m very excited to see what we come up with.

GSD: What do you hope students will take away from your courses?

AS: Two things, primarily: first, that your personal definition of environmental goods and evils positions you politically; and, second, that environmental knowledge is always produced in a cultural context. This second point has become a strange thing to teach in the age of “fake news” and “alternative facts.” Usually, the social production of knowledge seems like pretty esoteric deep theory, but now it feels like critical civic education.

There’s nothing wrong with information having politics – all information does – but there’s a lot wrong with intentionally using this to mislead people. Learning to be aware of the cultural contexts in which we and others come to understand “facts” doesn’t mean there is no such thing as lies. But if we teach our students that knowledge is objectively “true” or “false,” apart from the social contexts in which that knowledge was developed, then the culturally-embedded nature of all knowledge makes it easy for those with ill intentions to throw doubt on the process of knowledge-gathering, no matter how rigorous. They can then claim that intentionally-misleading information is no less true than, say, a peer-reviewed study or carefully triangulated investigative journalism. This has really impoverished civic debate.

If the cultural and political nature of knowledge production were taught earlier, to everyone, I think the politics of the knowledge wars happening right now would have less shock value. People would be more equipped to judge the validity of information within the context of its production, and our politics would be more sophisticated. So, in summary, I hope my students will leave class seeing themselves as more empowered citizens.

GSD: Did you have a favorite class in college or graduate school? What made it your favorite?

AS: At every stage of my career, there has been a class that radically changed how I see the world. I’m a social scientist because of Jim Howe’s undergraduate anthropology class at MIT, “Conquest of America” which is, I think, where I first learned how to question the inevitability of history and especially of Western-style development. When I then went on to pursue a Master’s degree in Anthropology at the University of Chicago, William Mazzarella’s “Commodity Aesthetics” was where I started to understand the political power of critical theory. In my doctoral studies in Urban Planning at MIT, Anne Whiston Spirn’s class, “Urban Nature and City Design” taught me how to read built and natural environments as cultural and historical texts, especially how to look for the contested visions and fights for social justice embedded in landscapes.

GSD: What’s on your reading list/watch list/play list right now?

AS: A few years ago, I started listening to “Nature’s Past,” a Canadian Environmental History podcast. It is wide ranging and always interesting. I started listening to it as something to do while baking bread, but then I kept wanting to take notes, and my laptop always ended up covered in flour.

My reading list right now is everything on the The Syllabus Project, a collaborative library created by Nancy Langston and Davey Fousey to highlight environmental writing by women and scholars of color.

But, in particular, I’ve been trying to find time to read Antina von Schnitzler’s Democracy’s Infrastructure: Techno-Politics and Protest After Apartheid, on water rights in Johannesburg. Maybe I’ll assign it to my class this fall!

GSD: Who’s your design hero?

AS: I mostly think about design through infrastructure. Right now, my design heroes are the community activists I’ve interviewed in the last few years who have fought to bring local energy decisions under participatory democratic control—for example, the “New Power” activists with Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, or the Southern Regional Council’s community organizers who, in the 1980s, tried to use electricity governance as a venue for expanding voter rights and racial equality.

These activists understand that infrastructure is also social structure. If you think about the ways we talk about renewable energy, for example, it’s often in the same breath as concerns about or hopes for economic growth, job creation, and revitalizing or protecting manufacturing, and it’s almost always implicated in environmental health. But energy technology doesn’t do anything social or environmental on its own; it depends on how it’s designed and implemented as a socio-technical-economic system. I’m really inspired by people who see the socially transformative potential of energy infrastructure and deliberatively work towards redesigning it in the service of greater social, economic, and political inclusion.

GSD: What role can design(ers) play in creating a more just, beautiful, and equitable world?

AS: Space is a way of organizing society, of facilitating or constraining action. Design and planning therefore have the potential to be revolutionary acts, from the smallest scale—say, turning a parking spot into a garden—up to the global— say, thinking about cities as the frontlines of climate change. As designers and planners, we approach the world with unique vision: we are trained to intuitively interpret the spaces we move through not as “given” but as “constructed,” and therefore we can always see the potential for them to be rewritten, to be made better.

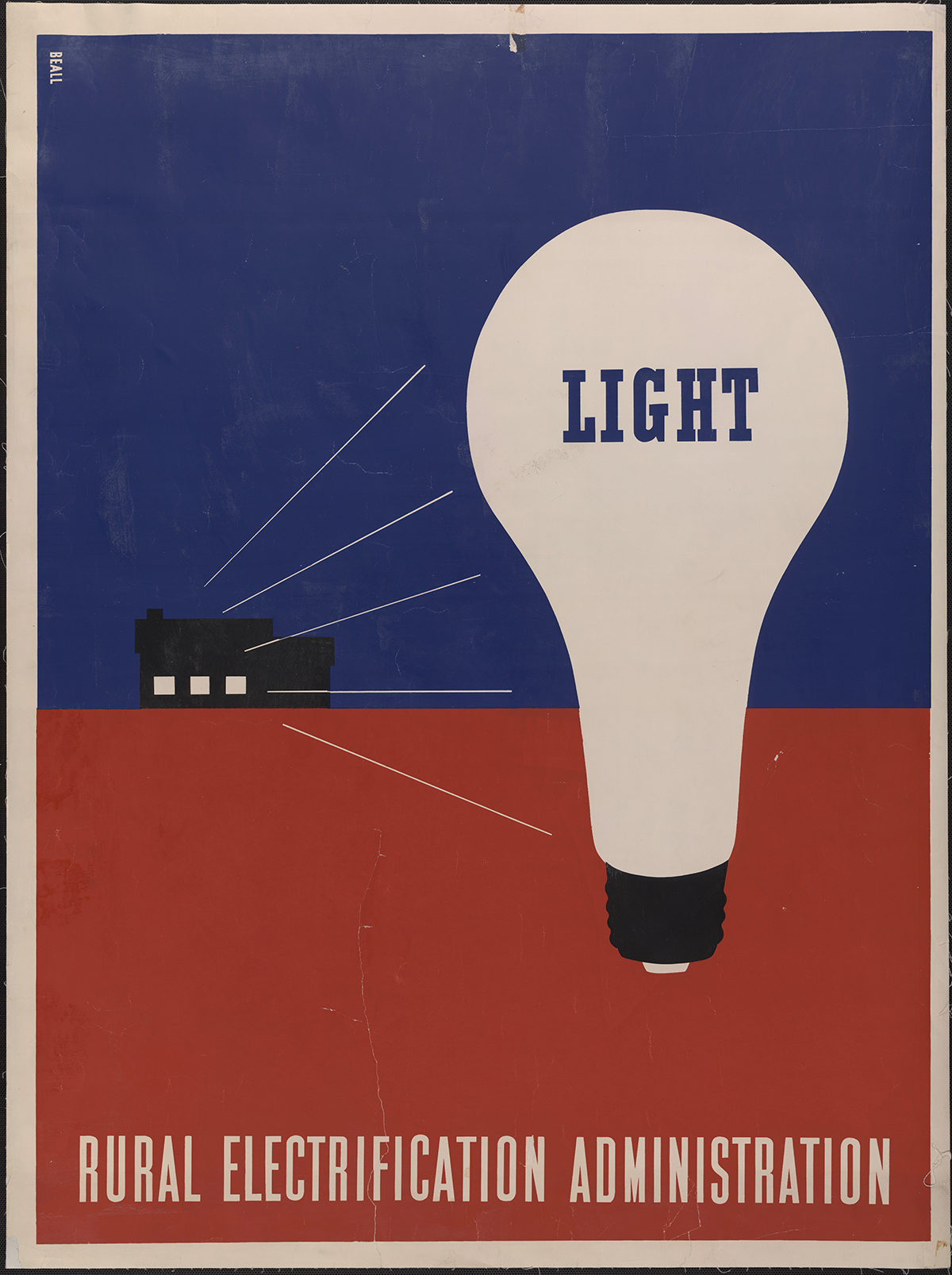

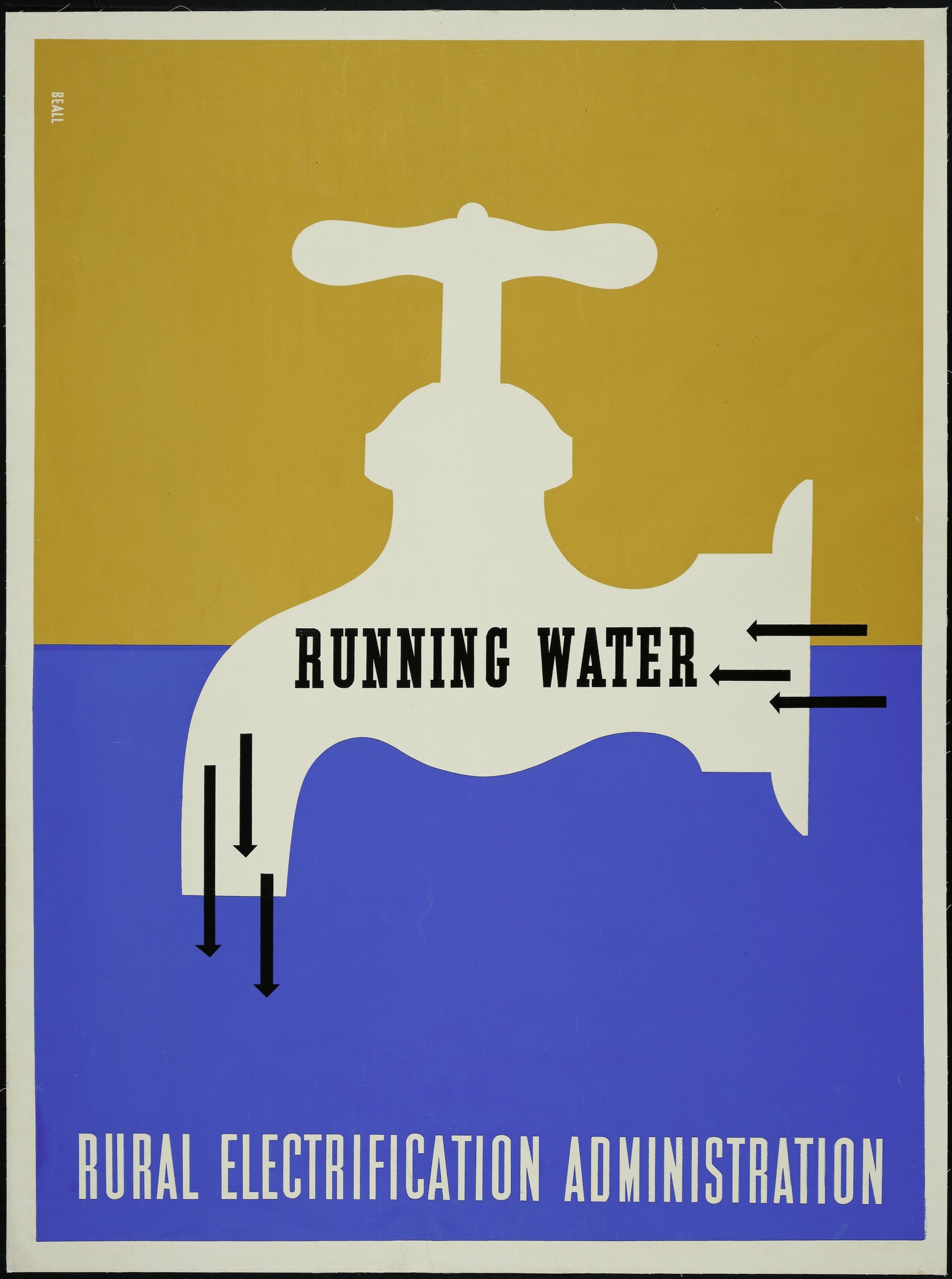

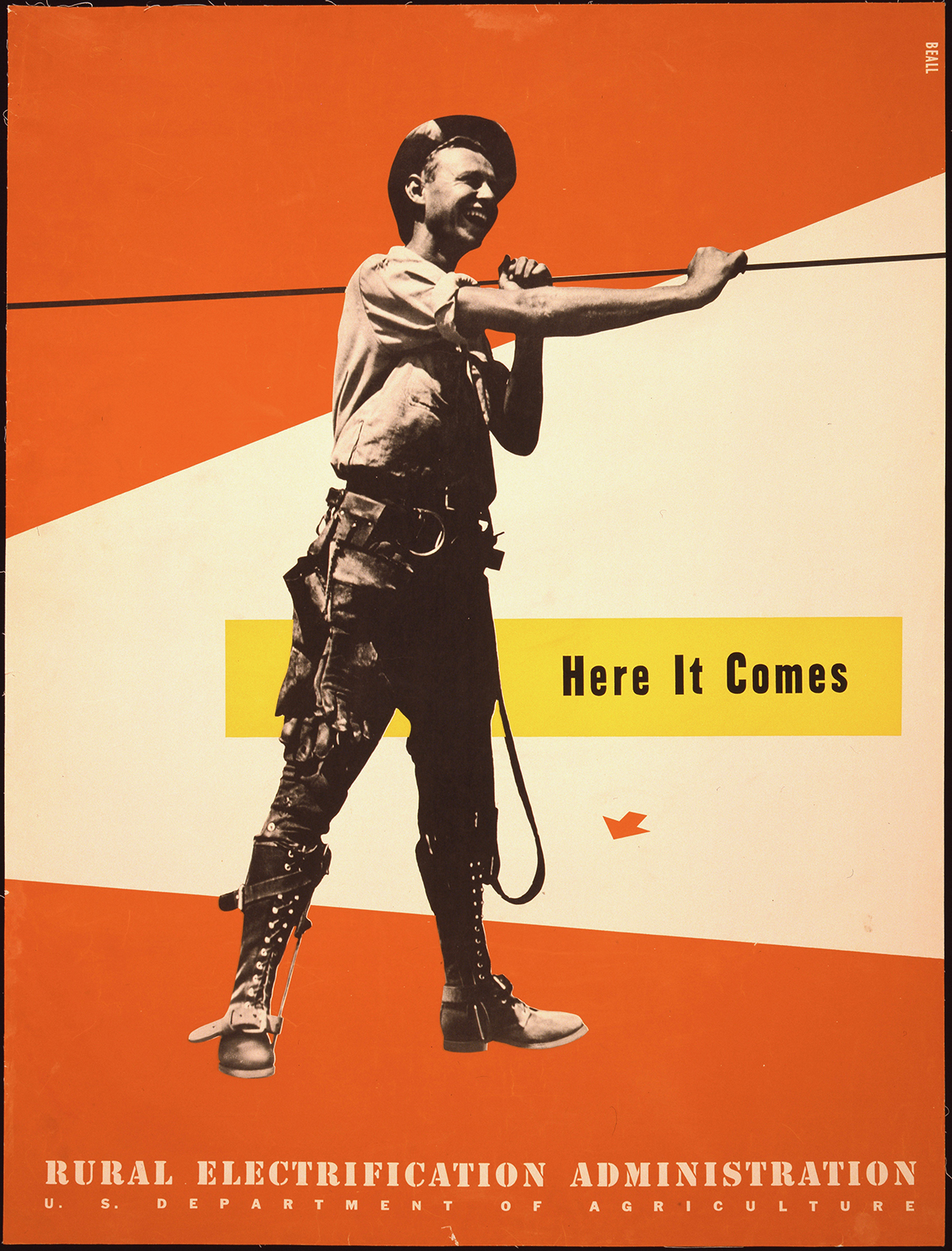

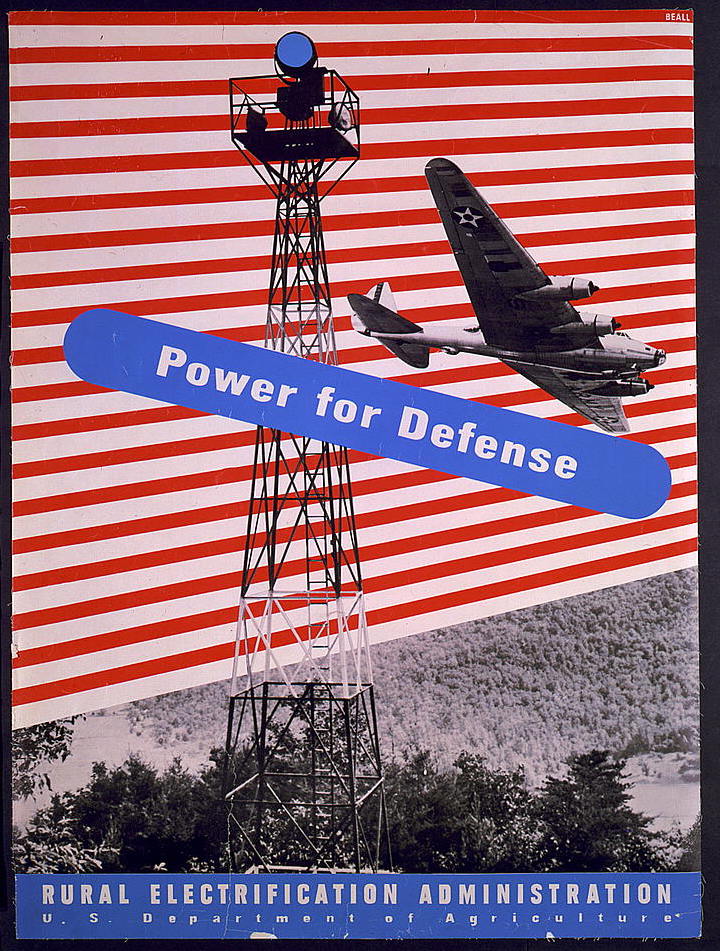

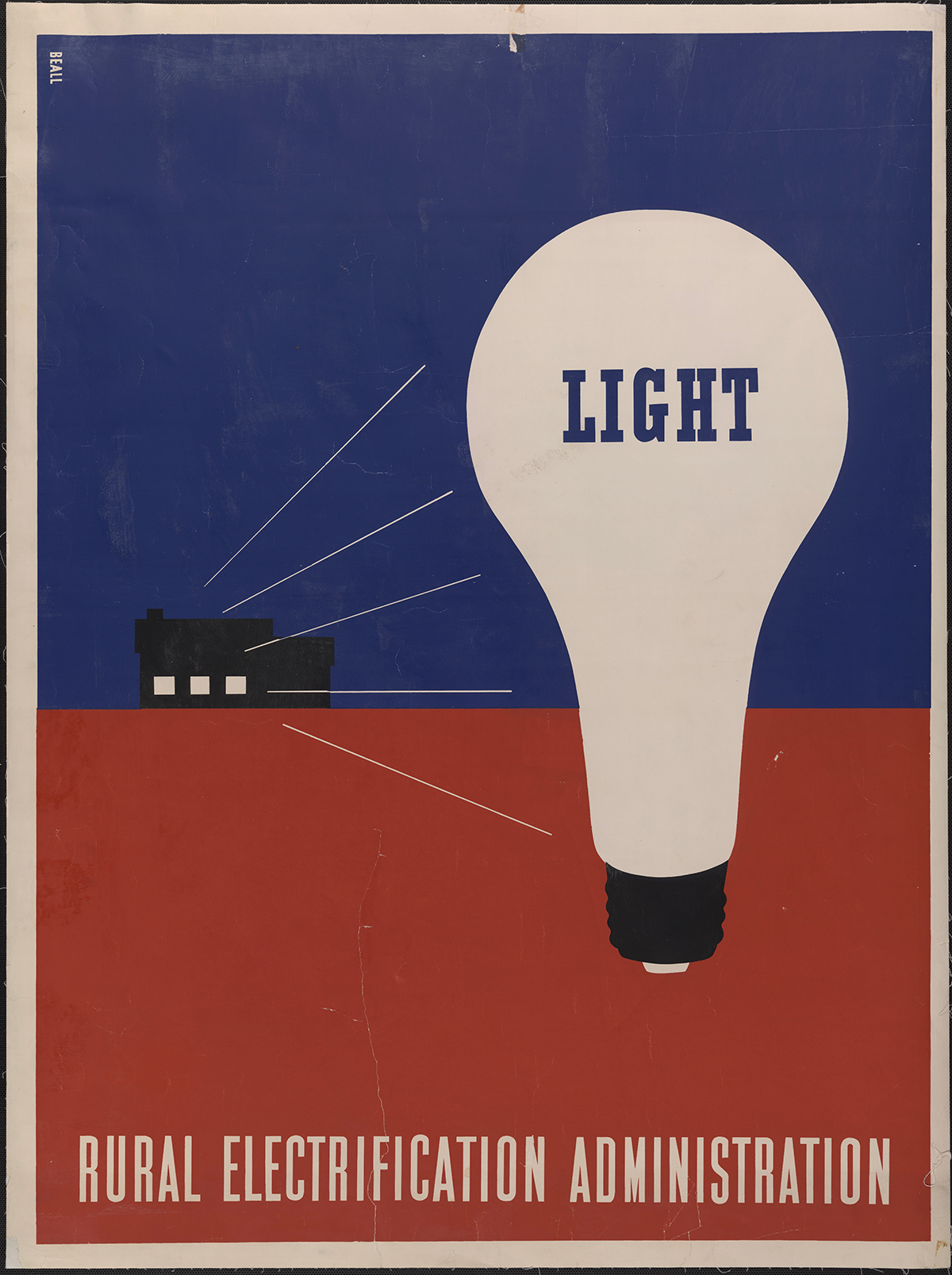

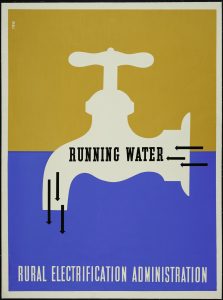

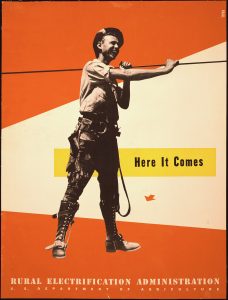

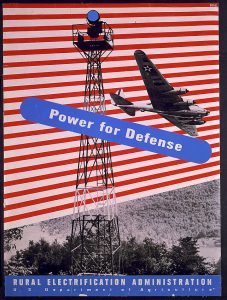

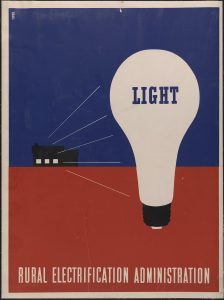

Spinak is currently working on a book about community-owned electricity and energy politics in the mid-twentieth century United States. The above posters, designed by Lester Beall in the 1930s, promoted a federal program that financed “electric cooperatives” across the country. Like many New Deal projects, the Rural Electrification Administration’s primary goal was national economic recovery—in this case, through encouraging decentralized industry, industrial agriculture, and wider access to consumer goods—an agenda that interacted in complex and contradictory ways with the local-scale, community-centered democratic ideals of the cooperative business model. The book explores how electricity raised critical questions about citizen participation in the American economy which we have yet to resolve.

Posters such as the ones above can serve as a reminder today to reconsider ideas of the nation as a coherent and coordinated economic entity and can raise interesting questions about the relationship between energy infrastructure and quality of life. For a more detailed exploration of the “graphic vernacular” of the New Deal, see art and design historian Michael J. Golec’s article, “Poster Power: Rural Electrification, Visualization, and Legibility in the United States” (2013). Golec argues that such imagery worked to construct the bureaucratic state in the mid-twentieth century, by both “render[ing] rural society legible” and “visualiz[ing] a future with electricity” that embodied ideals of efficiency and mass consumption.