Ireland’s northwestern borderland is a place that has changed a lot over the last two decades. For those living there, recent memory includes a time when the border was “hard,” meaning that it was marked-out with customs posts and military checkpoints. Until twenty years ago, two authorities–those from Northern Ireland on one side, and the Republic of Ireland on the other–could stop, question and search border-crossers, including locals whose daily commutes involved twice-daily crossings. Hassle and delay were facets of everyday life for residents, many of whom lived on one side and commuted to a job or school on the other. There was a degree of emotional discomfort to crossing the border, and it was an experience that could provoke a question that had no easy answers: Where do you think you belong? A distinction between the two sides of the landscape was reinforced by border infrastructure, which for many created an artificially-divided common ground.

Nowadays it is possible to cross the border without even realizing you have done so. Often the only indications are road markings that change from yellow to white, and most of the border’s 200+ roads are too small to have such markings. Two important international agreements are responsible for rendering Ireland’s border invisible: In 1993, the United Kingdom (including Northern Ireland) and the Republic of Ireland joined the European Union’s Single Market, which meant goods or services could be sold to member states within the EU without fuss. Customs posts closed, and the economies of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland began to grow together. The question of whether Ireland should have a border at all remained a key issue in Ireland’s politics even after 1993, especially in Northern Ireland, where the debate had spurred violence. That violent phase was known as the Troubles, and it drew to a close in 1998 with the Good Friday Agreement. This peace accord finally took guns and bombs out of Northern Ireland’s politics. The military checkpoints disappeared almost as quickly as the customs posts had, and the border became invisible. As a symbol on the map, the border remains contested but is no longer a confrontational element in the landscape.

As complex and fraught as cross-border communication and identity is, today the fate of the border region in Ireland is further complicated by the potential outcome of Brexit, the attempt to untangle the United Kingdom from the European Union. Leaving the EU is something the UK decided to do in a referendum three years ago, and after many setbacks it is now slated for October, 2019. It will make Ireland’s border the only land frontier between the UK and the EU. It is possible that the UK will leave the single market that day too, undoing the work of 1993. This could mean the return of custom checks at the border. Brexit could also damage the work of 1998, as the Good Friday Agreement allows for both Irish and British citizenship for the people of Northern Ireland, an arrangement that was more easily workable within the shared context of the European Union.

Harvard design and anthropology students arrived in Ireland’s northwestern borderland in March 2019 as part of a research trip to where the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland meet, to understand the landscape and its potential within the framework of impending political and social transformations. They visited the northwestern borderland, including the city of Derry/Londonderry, north Donegal and Lough Foyle. I met Gareth Doherty, assistant professor of landscape architecture and principal investigator of the research project Atlas for a City Region: Imagining the Post-Brexit Landscapes of the Irish Northwest, in a café near Derry/Londonderry. As part of the research project, Doherty is leading a seminar at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, Design Anthropology: Objects, Landscapes, Cities, as well as a studio with Professor Niall Kirkwood, Field Work: Brexit, Borders, and Imagining a New City-Region for the Irish Northwest, which imagines how the region will develop over the next 50 years or more.

An underpinning idea was that researchers can gain a lot by living in communities and trying to understanding them from the inside, from the ground up. “This can be a useful complement to the planning processes,” he explained. Traditionally, ethnographers and anthropologists work alone, and often spend extensive amounts of time in the places they are studying. The field research did not have much time–just a few weeks–but they had plenty of people–a dozen landscape architecture students and seventeen design anthropology students.

The students traveled to the borderland to explore, talk to locals and then pool what they had gathered. The team was embedded in urban zones like Derry/Londonderry, in villages and on farms. They were looking at practical issues–food systems, transportation, border technology and the fishing industry–but also at more abstract factors, such as sexuality, music and concepts of home. Anthropologists, said Gareth, are good at asking why, but this project was also about getting them to think into the future and consider where a society’s dynamics may lead. Architects, planners, and landscape architects, on the other hand, are well-practiced in imagining futures, so during this project they were encouraged to consider the rationale for their creations.

The students arrived with some set tasks and issues to investigate. Firstly, they were asked to identify if the area they were exploring could be accurately described as a region, a region with an international border running up the middle, but nonetheless a coherent place. “What do you think the limits of this region might be?” I asked. Gareth unfolded a map of the area, ran his finger around it, indicating an area spread equally across both sides of the border about 70 miles wide and 70 miles high. It encompassed Derry/Londonderry, Strabane and Letterkenny, but the outer edges of this proposed region were deliberately vague. “We didn’t want to simply draw another border,” says Gareth.

It seems fair to call this area a region: The economic pull of Derry/Londonderry is felt across the border in rural Donegal, and cross-border roads are busy (Derry/Londonderry was where we often went to shop when I was a child, despite the checkpoints. Once we had got beyond the dislocating experience of the border there was not much that was alien about what we discovered on the other side).

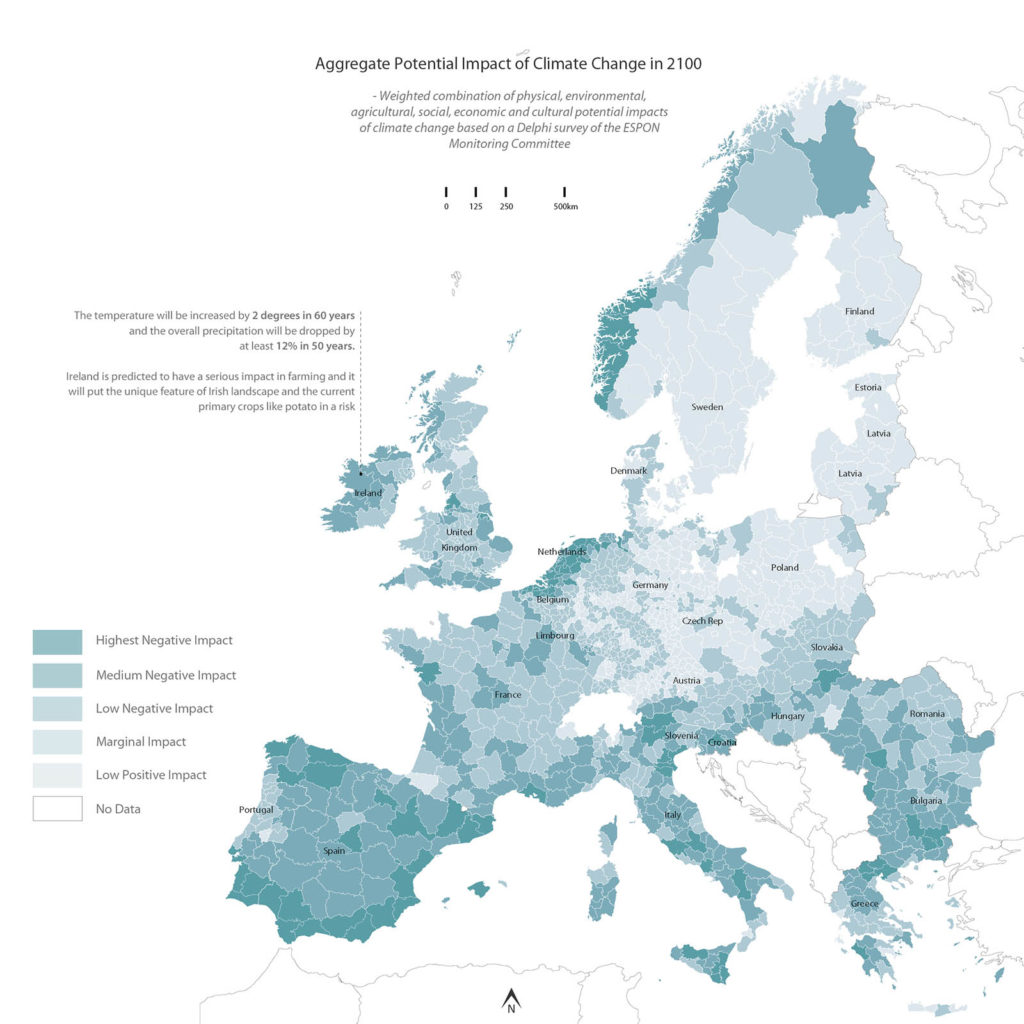

The students were asked to consider how this region could be affected by climate change. Broadly speaking, as it runs from east to west, Ireland’s border goes from high and hilly to flatter and more open. To the northwest, horizons get lower; the sky gets bigger and the border joins its one major river, the Foyle, which widens on its way to the sea. Because of its low elevation and the fact that it’s hemmed by water on three sides, this land and economy will be hugely affected by a rising sea level. The landscape’s delicacy is suggested in old maps of the area. In the 1600s, a large headland called Inishowen, now firmly attached to the rest of Ireland by a neck six miles wide, was considered a separate landmass. This shift is reflected in the area’s original name: Inish means island. The landscape was likely boggy and prone to flooding before the advent of drainage systems. Now, several miles from the sea, round pebbles as if from a beach are still to be found beneath a shallow layer of soil, an indication that once upon a time the tides came much further in.

On their daily explorations, the students were encouraged to rely on chance, as Gareth reasoned that chance encounters can be very rich. At first this might seem a haphazard way of going about things, but if there are two dozen people out there relying on chance every day for a couple of weeks, then you can be confident of returns. Planning too much, Gareth suggested, can lead to bias. How can one plan without relying on the preconceived? Chance means freshness and immediacy. Chance also means being unprepared, so students had to rely on their humanity and instincts to simply get along with the people they met and learn things from them. The students did not hand out questionnaires; they talked and listened. One student reported that walking their host’s dog was a great way to get into conversations with locals. Sohun Kang, from South Korea, went to places open for visitors, such as community groups, public libraries, and a boxing club. He found that one encounter could lead to another. Kiran Wattamwar, who is from India, called into a community center on a lucky day and within an hour she was “engaged in a discussion with eight people, friends of friends who had all been called over by someone else they knew.”

Another of the students’ tasks was to examine how people live on a cross-border basis. Kiran wanted to find out how people’s use of telecommunications was shaped by the border. Despite the fact that there are no additional roaming or cellular charges across the border region, Kiran discovered that some people preferred having two phones, compartmentalizing their lives on either side of the line. Having two phones is indeed the mark of many borderland citizens, as is having two separate currency pockets for British Pounds and Irish Euros.

Ashutosh Singhal, originally from Mumbai, examined the aquatic border and the rules around national fishing rights, visiting fishing villages like Greencastle and Buncrana. For generations, fishing has been an important part of the region’s economy. Fishing fleets are permitted anywhere around the UK and Ireland. Singhal mapped opportunities for socio-economic development in the fishing communities of Inishowen; “opportunities that could be used to by-pass the implications of Brexit”.

The students’ final task was to consider how Brexit might affect their research area and people’s lives in the region generally. It is certainly a concern for the fishing fleets. Ashutosh warned that, “the consequences of a Hard Aquatic Border on these fishing communities will be dire.” Meesh Zucker, a City Planning graduate student at MIT, focused on the visibility of marginalized identities in the region, particularly LGBTQ+ people, and spoke to many who would rather see Brexit cancelled. Some fear identity profiling at the border, while transgender individuals were concerned that they may be stopped from receiving healthcare on one side of the border or the other. Some told Meesh that they feared Brexit “might lead to events similar to those that took place during the Troubles.”

This is far from a minority concern. In the region these students visited, and all along the borderland, there is real anxiety that the frontier’s invisibility will turn out to have just been a 20-year phase–a short, productive hiatus from the border’s overarching story: confrontation. This would be a real shame because, as this group of students and researchers discovered, so much is just getting started.

Garrett Carr is the author of The Rule of the Land: Walking Ireland’s Border. He is a Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing at the Seamus Heaney Centre, Queen’s University, Belfast, Northern Ireland. Atlas for a City Region: Imagining the Post-Brexit Landscapes of the Irish Northwest is sponsored by Derry City and Strabane District Council and co-sponsored by Donegal County Council.