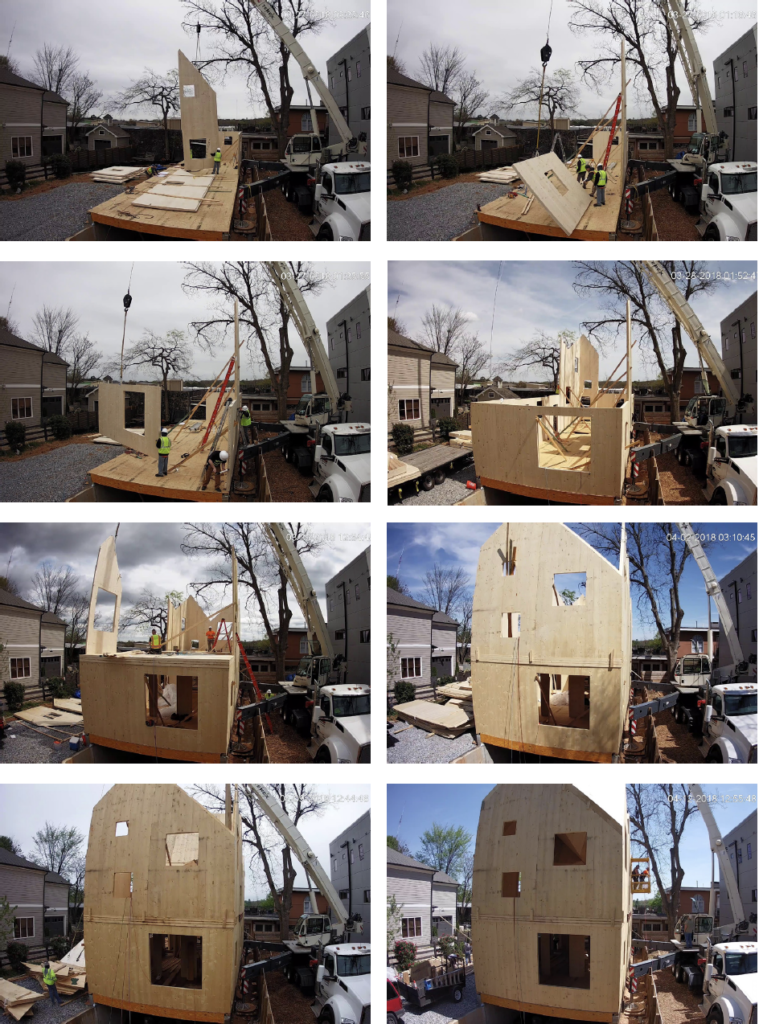

On the first day of the construction of Haus Gables–after 11 trucks had ferried 87 panels of cross-laminated timber from Savannah to Atlanta–Jennifer Bonner was stuck in Cambridge due to a last-minute travel snafu. So she watched her first built project come to life via security camera from a thousand miles away.

“The whole thing looked like an architectural model being assembled in place,” the designer recalls. “If you squint your eyes, watching the panels being installed at that scale, one could imagine, ‘This is the way we cut up materials—chipboard, foam core, and whatever else is on our desks—and make models.’”

Sitting on an 18-by-55-foot floor plate in Atlanta’s Old Fourth Ward, Haus Gables represents the third physical iteration of a research agenda that Bonner has been pursuing at her firm, MALL, over the past decade: What happens when architects start with the roof? If we let roof typology organize the rest of a building, might we start generating new forms of urbanism?

It’s a concept Bonner first presented in her 2014 exhibition, “Domestic Hats.” After studying roof typologies throughout Atlanta, she cataloged 50 different houses and milled their roofs as foam “hats.” Her next iteration, “The Dollhaus,” presented a 1-to-12-scale wooden model of a suburban home topped by oddly gabled rooflines. In producing each exhibition, Bonner researched, metabolized, then reframed the common language of suburban roofs, in a nod to the unseen complexities and cultural residues embedded within something so ordinary.

It’s a concept Bonner first presented in her 2014 exhibition, “Domestic Hats.” After studying roof typologies throughout Atlanta, she cataloged 50 different houses and milled their roofs as foam “hats.” Her next iteration, “The Dollhaus,” presented a 1-to-12-scale wooden model of a suburban home topped by oddly gabled rooflines. In producing each exhibition, Bonner researched, metabolized, then reframed the common language of suburban roofs, in a nod to the unseen complexities and cultural residues embedded within something so ordinary.

Haus Gables is “The Dollhaus” brought to life. And it was an enormous risk: Bonner took on the role of designer-as-developer-as-financier, shouldering all project liability on her own.

“The process was actually incredibly liberating,” Bonner says. “This is what the architect should be doing: building, but also conceptualizing architecture, with one foot in academia, in experimentation.”

MALL is an acronym for “Mass Architectural Loopty Loops,” and with Haus Gables, Bonner has produced the sort of project that the firm promises and celebrates. She began by taking three pairs of gables and organizing them such that, from the front-curbside view of the house, the roof appears at a typical gable pitch. However, thanks to a clever rotation, the observer sees that the traditional gable outline is a bit clipped, making something feel slightly off.

The underside of this multi-gabled roof is a folded, geometric ceiling on the home’s interior. In the interest of revealing this ceiling geometry, Bonner manipulated cross-laminated timber (CLT) like a piece of origami. This non-traditional approach required a rethink of the horizontal structural systems common to roofs, like the eave-to-eave connections that often double as an attic or loft floor. Bonner tackled this challenge alongside Haus Gables’s project engineer Hanif Kara, a longtime mentor as well as Professor in Practice of Architectural Technology at the GSD and design director of structural engineering firm AKT II.

“With Haus Gables, there are no ties in the roof, but the roof’s form acts as a shell structure through the folding of the CLT,” Kara observes. “This system is rigid in itself. We then have to take care of externally applied horizontal forces, such as wind.”

It is from this roof geometry that the inflections and space of the rest of the house follow, allowing Bonner to max out the modestly-sized floor plate. This effect, in turn, satisfied Bonner’s ambition to create wide, airy volumes within the 2,200-square-foot space. A viewer can see up to the ceiling from a few points on the first floor, and the inverse applies on the second floor: Someone standing there can see a periphery of spaces on the ground level.

“It’s four times bigger inside than it is outside,” says Mack Scogin, in an interview with Metropolis. Scogin is Bonner’s colleague at Harvard Graduate School of Design, where he is the Kajima Professor in Practice of Architecture. “As we say in the South, she’s somethin’ else.”

The CLT panels composing Haus Gables’s roof were among the 87 that Bonner had flip-milled at KLH in Austria. Each panel was designed digitally to the millimeter—Bonner checked the final design file by hand six different times—and numbered one through 87—“like cartoon panels,” Bonner observes.

The CLT panels composing Haus Gables’s roof were among the 87 that Bonner had flip-milled at KLH in Austria. Each panel was designed digitally to the millimeter—Bonner checked the final design file by hand six different times—and numbered one through 87—“like cartoon panels,” Bonner observes.

“Precise industrialized off-site manufacture is one of the biggest advantages we have, since we have to have fully drawn, designed, and calculated systems, helping us avoid lack of fit on site,” says Kara. “This means there is no casualness at all in the binding of macro and micro detailing of connections. The brute force of computation and digital manufacturing is now so powerful it allows us to examine forensically the structural stresses and manufacturing constraints all in one model. This collapsing of process is all very exciting.”

After milling, the CLT panels were loaded onto three open-top containers and shipped to the Port of Savannah in Georgia, where they were packed onto hot-shot trailers heading to Atlanta. All 11 trucks were staged to receive and deliver the panels in the order in which they were to be installed, with a crane on site ready to lift the panels into place.

Bonner smiles when confessing that nearly every subcontractor who walked through the door of Haus Gables immediately scratched their head. She explains this was because not many were accustomed to working with CLT—plumbers and electricians wondered where their pipes or wires would go within walls that are solid. But perhaps the real issue was that they couldn’t find the front door.

“Yeah, there’s no front door,” Bonner admits. Instead, visitors enter through the garage, a bright-white, glossy space that reads more art gallery than automobile storage. From first glance, Haus Gables defies ordinary expectations of “house.” Faux finishes dash across the interior, with material elements including vinyl, terrazzo, and ceramic tile placed like massive stickers on the CLT walls. The master bedroom is set off by gray vinyl that resembles concrete; the dining room is bathed in a yellow vinyl that looks like marble; the kitchen is all black terrazzo. The CLT walls were whitewashed to achieve a milky hue, in effect freezing them in time to avoid yellowing.

Things get weirder on the outside. Eschewing wood siding, Bonner sought an abstract material for the exterior facades, wanting something ordinary that could be found in big-box stores. She settled on cementitious stucco. On two facades, she applied a brick stencil, an eighth of an inch thick, to the final trowel of stucco. Then, at the last second of application, she blew millions of tiny glass beads—the material used in reflective traffic paint—in a “dash finish,” creating a shimmering, reflecting façade.

In other words, the exterior is composed of fake bricks that shine like diamonds. Here, Bonner references Mary Corse, an American artist fascinated by perceptual phenomena and light, who “painted” with glass beads in the 1970s.

“I wanted to be just a little devious,” Bonner observes, noting she was unsure how brightly a 55-foot wall would shine until she saw it in action. The phenomenon doesn’t photograph: “You’ve got to be there to see it,” she says.

These various elements serve basic representational purposes, but they also get at a Southern tradition that fascinates Bonner: faux finishing, a practice with historical roots in the American South—originally a manifestation of a “fake it ’til you make it” philosophy. “There’d been an idea of, ‘We can’t afford certain materials, so let’s paint it, or apply an appliqué, or get a really thin veneer of real material,’” she says. “This was part and parcel of the notion of the house as built in the South.”

A native Southerner, Bonner waxes poetic about an early-career experience she had in deep-rural western Alabama with Rural Studio’s Samuel Mockbee, who instilled in her the notion that there can be immense intellectual value in nearly any place. She also points to Southern projects like Paul Rudolph’s Tuskegee Chapel and Mack Scogin and Merrill Elam’s Clayton County Library—projects of profound experimentation that lie outside today’s architectural canon.

“There are all kinds of radical projects that have happened in the South,” Bonner observes, “but that aren’t a main reference in our teaching. They are these very specific, radical experiments. I think they motivated me to create more of a dialogue around architecture in the South.”

Take Haus Gables out of its Old Fourth Ward site and, with its all-white exterior, it may read as high-modern, Japanese residential. Or, with its monolithic, overhang-free exterior, something from Switzerland. The dominance of CLT evokes Scandinavia. But we’re in Atlanta—the “Dirty South,” as Bonner reminds me. (She’s authored a book series entitled A Guide to the Dirty South, with editions focused on Atlanta and New Orleans.)

“These materials, these stickers, these colors, this kind of pop, the faux finishes—these were my ways of shaking things up a little bit,” Bonner says. “If I would say one thing about the South, it’s that it’s complicated. There needed to be a lot going on with the house to make it complicated.”

In her office, Bonner shows me a drone-filmed video of Haus Gables at dusk. As the lens pans upward, Haus Gables looks more and more like a model, sitting in front of an Atlanta skyline largely shaped by another of Bonner’s Southern design heroes, John Portman.

“I admire the invention of a typology—the super atrium—out of downtown Atlanta, and of Portman working away on his kind of architect-developer model in inventing things,” Bonner says. “He was inventing, and I’m trying to invent. To build this in Atlanta was a very important move for me.”

Developing and constructing Haus Gables involved a fair share of 20-hour days, in which Bonner would travel from Cambridge to Atlanta and then back, allowing her to teach studio at the GSD while also leading her inaugural built project to fruition. If Haus Gables is conceived as a model, a representational device, then it proved instructive for both its architect and her students.

“My students knew what I was undertaking, knew how big it was, and were so excited to hear about the process, to see a member of the junior faculty building this project,” Bonner says. “They asked me to show them the behind the scenes, the difficulties of doing such a project, what was I coming up against. I wasn’t giving them an academic lecture about a house; I was giving the down-and-dirty version.”

“My students knew what I was undertaking, knew how big it was, and were so excited to hear about the process, to see a member of the junior faculty building this project,” Bonner says. “They asked me to show them the behind the scenes, the difficulties of doing such a project, what was I coming up against. I wasn’t giving them an academic lecture about a house; I was giving the down-and-dirty version.”

In a continuous braiding of research, practice, pedagogy, and mentorship, Bonner and Kara are currently planning a Spring 2020 option studio entitled “Mass Timber and the Scandinavian Effect.” Haus Gables stands as only one of a handful of CLT-composed houses in the US (the first, in Seattle, was designed by Susan Jones, a fellow GSD alumna). With Haus Gables as a real-life model, Bonner’s experimentation with CLT, like her decision to design from the roof, questions the very rudiments of how we design.

“One interesting thing that Hanif and I have always been discussing is how this house is really a proof of concept,” Bonner says. “To build a domestic hat at one-to-one, out of an innovative wood product like CLT, in a place that has not yet built with it—there’s a lot to figure out. It’s literally throwing all of our energy and resources into building a proof of concept.

“Maybe I’m demonstrating or rehearsing the same kind of thing the students do, which is to have a position on architecture, an agenda, a thesis,” she continues. “Work it conceptually and intellectually, and then try to deliver it. It’s like working in studio, where you’re trying to dig at the conceptual thesis of an architectural project, and then you culminate in a final review. Haus Gables is the culmination of a body of work that I’ve been working on for the past five years.”