By the time Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. founded the world’s first landscape architecture program at Harvard in 1900, he and other landscape architects, like his father, had devoted much of their careers to addressing some of the era’s greatest social challenges. For Frederick Law Olmsted, confronting the institution of slavery and the cotton economy was of profound importance. For Charles Eliot, advocating for progressive land trusts and conservancies was vital. Eliot shaped much of how the Boston region would develop in the coming century while conceptualizing a framework of conservation of natural resources that would be applied around the world.

As anti-immigrant and nativist anxieties germinated in turn-of-century America, the establishment of a landscape architecture program at Harvard, under the presidency of Eliot’s father, Charles William Eliot, presented a novel—and enduring—expression of design’s potential to ameliorate the growing pains of an evolving society.

Poets, prophets, and reformers are all picture-makers, and this ability is the secret of their power and their achievements. They see what ought to be by the reflection of what is, and endeavor to remove the contradiction.

“In its original formulation, the field of landscape architecture was seen to hold great promise to address societal and environmental conditions through design,” observes Charles Waldheim, the Graduate School of Design’s John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture and Director of the Office for Urbanization. “While neither Eliot would have used the term ‘social justice,’ they did see the development of landscape architecture, the building of reform parks, the conservation of natural resources, and the building of modern sciences to support these activities as directly addressing the lives of people.”

Waldheim offers perspective on these threads with the exhibition Big Plans: Picturing Social Reform, on view through September 15 at Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Waldheim, the museum’s Ruettgers Curator of Landscape, collaborated with assistant curator Sara Zewde (MLA ’15) on the show, inviting viewers to see how landscape architects of the past, engaging with photographers and the media, advocated for social reform, and how the legacy of their work speaks to some of today’s urban and cultural challenges. “Social justice, equity, and reform are not new topics for landscape architecture—rather, they are at its origin,” Zewde notes. “This exhibit calls for a new look at the roots of the discipline.”

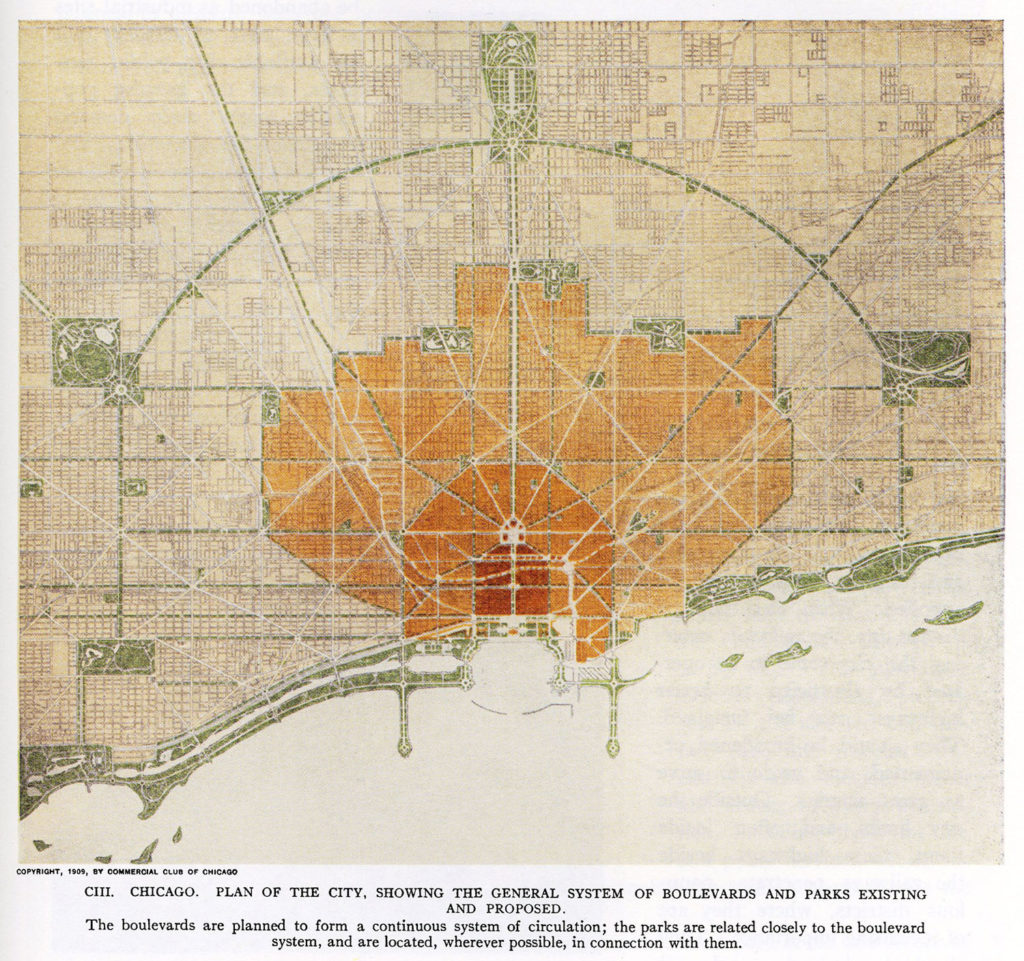

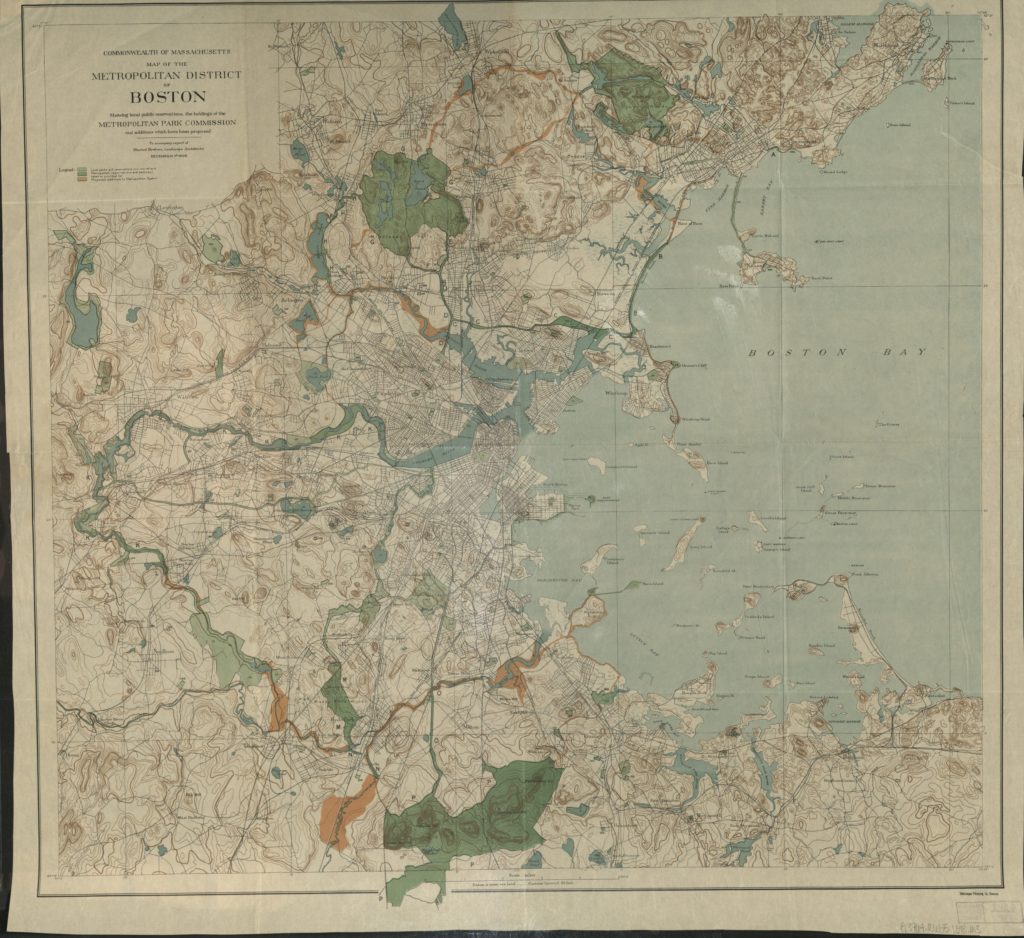

Waldheim and Zewde have curated a set of city plans, archival materials, historical maps, and photographs in order to demonstrate how, from its inception, landscape architecture as a field has invested itself in preservation, social justice, and economic equality. Zeroing in on the late 1800s and early 1900s, Big Plans features large-format urban plan drawings and small-format documentary street photographs, especially the work of photographer Lewis Wickes Hine. The exhibition considers central questions that intertwine visual media and landscape: How do pictures illustrate the conditions in our city now, and inspire us to improve them for the future? In other words: How do visual images support progressive social reform?

Olmsted’s career offers various entry points to these questions. As Zewde observes, Olmsted was first appointed superintendent of New York’s Central Park in 1857, as America was on the cusp of the Civil War. He advocated, through writing, for the end of chattel slavery and for a reconsideration of what society would need to do in order to overcome the “stain of slavery.”

“Olmsted and Eliot’s progressive and urban reform works of the late 19th century can be seen in the context of a country not far removed from that war, and engaging directly with those questions,” Zewde says. “Political and economic tensions remained high into the late 19th century as cities were witnessing intense rural-to-urban migration, industrialization, and immigration—forces that would prompt Olmsted and Eliot’s ‘Big Plans,’ and the formation of the discipline of landscape architecture.”

In Big Plans, Hine’s photography chronicles living conditions as experienced by immigrants in turn-of-century Boston. Like Hine’s broader body of work, which documents the working lives of children forced into industrial and agricultural labor and enduring soul-breaking conditions, these images demonstrate Hine’s commitment to advocacy and social reform. The large-format maps and urban plans in the exhibit encourage the viewer to envision the connection between Hine’s emotionally compelling images and the more orderly—but equally reform-minded—planning and design work led by Olmsted and Eliot.

Waldheim and Zewde complement the exhibition’s core displays with interactive video and multimedia. Long-format video offers contemporary voices discussing and analyzing some of the work and themes on display, and “Map This”—an ongoing community-engagement project—invites viewers to help generate alternative mappings of greater Boston.

One of the show’s most evocative features, though, is at its entry wall. There, Waldheim and Zewde highlight a quote from Frederick Douglass, taken from a lecture Douglass presented in Boston’s Tremont Temple on December 3, 1861:

“Poets, prophets, and reformers are all picture-makers—and this ability is the secret of their power and their achievements. They see what ought to be by the reflection of what is, and endeavor to remove the contradiction.”

As Zewde observes, the power of what Douglass calls “picture-makers” is connected less to a specific medium and more to the process and thought behind envisioning or illustrating an idea or a moment.

“Rather, the power he describes is embodied in the process itself—the process of visioning the ‘is’ and the ‘ought,’ in so far as this is the first step toward bringing them in closer union,” Zewde says. “Digital techniques and contemporary media may open up new vantage points onto those visions, but ultimately these are tools to be employed in the greater pursuit of Douglass’ secret power.”