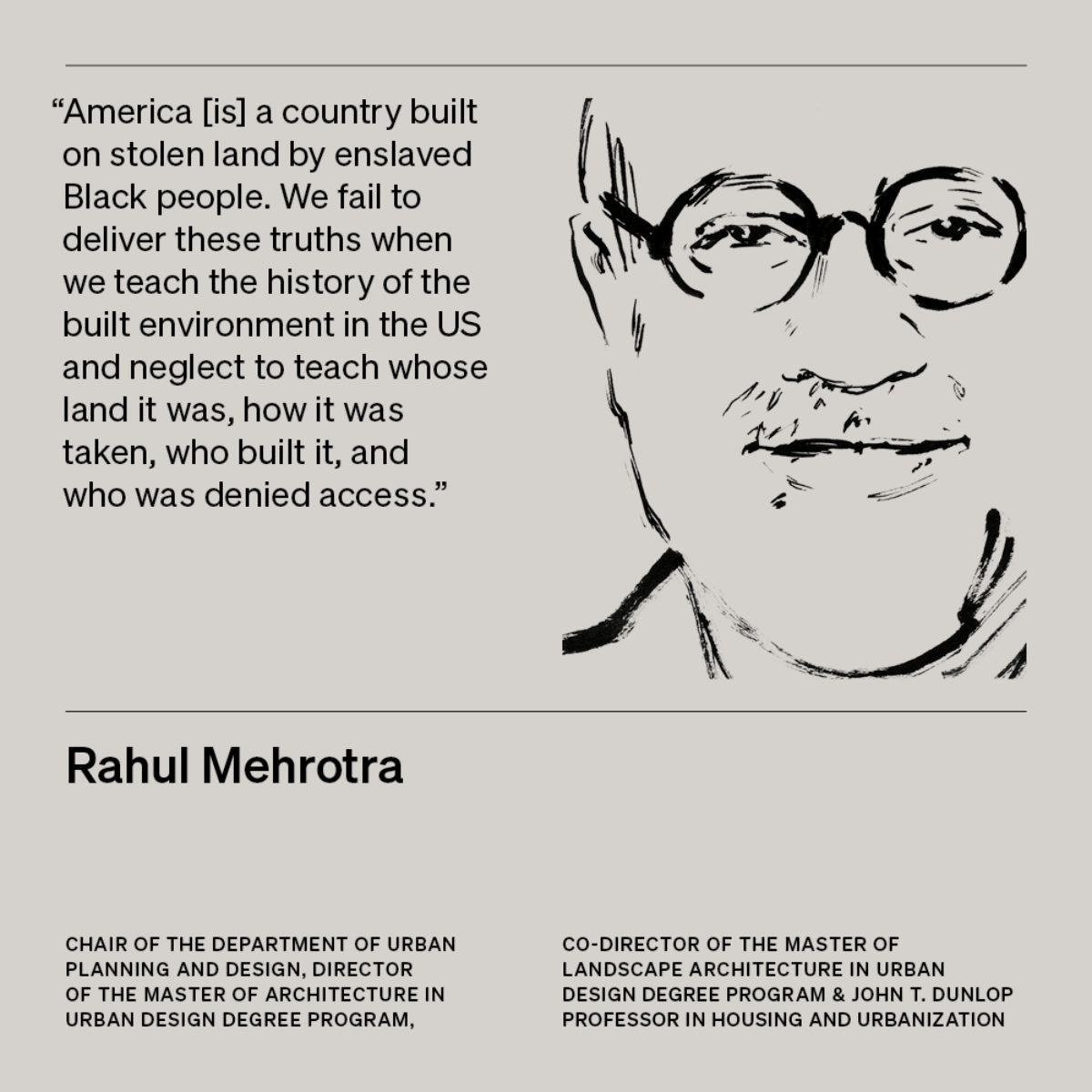

Rahul Mehrotra, Chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design, John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization, Director of the Master of Architecture in Urban Design Degree Program, Co-Director of the Master of Landscape Architecture in Urban Design Degree Program

As an architect and urban planner working in the US and India, how do you understand the role of architecture and design in contributing to systemic inequity? How can architects and designers use their work as tools to fight for underrepresented communities that have been targeted by structural racism and its spatial manifestations?

The physical form of cities and architecture are critical instruments with which we bring societies together or with which we separate and polarize them through zoning, redlining, urban renewal, and so on. What I have learned from my work in India is that architecture, urban design, and planning are not always the solution to the problem. Sometimes they are the problem.

Furthermore, I believe that architects and designers must not let design disciplines get co-opted into perpetuating biases and divisions in society. We should have the confidence to go into a project and call out the limitations inherent in the way it has been defined. We need to have the integrity to advocate against a project—especially if it is positioned to merely symbolically try to solve a problem, whether it’s racism or other institutional inequities. Sometimes convincing a client or a constituency to not do the building or project is the more appropriate solution.

I believe our aspiration as professionals should be to recognize our agency as well as our limitations. But unless we understand issues like racism at a structural level, we won’t even get there. That is an education that our faculty, and by extension our students, need. This is something I am deeply concerned with as a teacher—in today’s culture, everyday crises, fears, and concerns are expanding at an exponential rate, but often our sense of agency as designers is diminishing at the same rate. I would not want a generation who will keep nuancing their understanding and expanding their fields of concerns as students, but then graduate and find they do not have the tools to influence the environment and the issues that they are committed to. All architects, planners, and designers must maintain a close correlation between their concerns and their influence; the wider apart those get, the more cynical and jaded you become, the more your work becomes commercially focused, or you try to justify it through other ways that often harm the planet and society.

How does your experience growing up in India and recently becoming a citizen of the US shape your perspective on the racial justice movement happening across the country? How does it impact your pedagogical approach?

I carry a very particular experience as an immigrant, and as someone who has faced discrimination and racism. Having said that, my understanding of American history is limited. But I note that this is a common problem among international students and often with my American colleagues. In applying for American citizenship, which I received just a couple of years ago, I quickly learned that the kind of history you’re expected to know when interviewing for citizen status is one of American exceptionalism. For example, they test your knowledge of which president issued the Emancipation Proclamation, but never ask you to study and familiarize yourself with the brutalities of slavery that led up to it.

I find a parallel here to my student experiences in India, where I became aware of what came to be known as “subaltern studies.” This was a group of Kolkata intellectuals active in the 1970s and 1980s who wanted to reclaim their history in postcolonial studies and critical theory, and did so by gathering alternative histories that hadn’t traditionally been told in India’s elite intellectual circles. They were focused on subalterns (people of inferior rank or station due to race, class, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, or religion) as agents of political and social change.

They attempted to propel the rhetoric of emerging political and social movements to go beyond highly visible actions like demonstrations and uprisings to engage with forms of productive action. Their fight for “truth” and its representation resonates with the telling of the history of America, a country built on stolen land by enslaved Black people. We fail to deliver these truths when we teach the history of the built environment in the US and neglect to teach whose land it was, how it was taken, who built it, and who was denied access.

When we talk about the Black Lives Matter movement and racial justice issues related to Black communities, I ask what it means for the curriculum taught at the GSD, as much as for design at large. Students and faculty are challenging the integrity of the “heroes” in the canons of architecture, landscape, and design more broadly. And they are asking for many more lenses to understand the biases that influence our disciplines through the blind worship of these icons in the profession. They are rightly demanding a far more complex and nuanced pedagogy, to better understand and critique the heroes, typologies, and city forms we’ve come to hold sacred as precedents. If we don’t understand the embedded stories and the subaltern voices that have led to the construction of forms, and their related histories, we will perpetuate these injustices forever.

How can we broaden the spectrum of lenses that expose students to these different biases?

I believe that while individuals and curriculum are important, there is a critical need to look at the underlying issues and structures of society that people unknowingly perpetuate. New Deal programs, redlining, and urban renewal all had underlying biases that displaced Black people for generations and constructed a singular dominant imagination of the nation around a filtered narrative of American exceptionalism. As faculty and students, we must sharply focus our learning and attention on the history and theory of systemic and structural issues so that we are equipped to undo and reimagine the problems our disciplines have perpetuated.

Teaching has to straddle both ends of the spectrum. It’s not just about making people aware of these issues, it’s also about addressing, reimagining, and remaking the underlying structures of the institution: how departments are organized, how the silos of coursework are organized, what we include and what we knowingly or unknowingly leave out, and how we interact and share resources with the Cambridge and Greater Boston communities.

Our locality is where we can begin. We need to rethink our structures, how we organize events, public programming, and the platforms we set up for conversations in order to see problems as more ecologically and intrinsically linked. By slicing issues into silos, we don’t get the interconnectedness; when we look through one lens, we are limited in action by what we can see.

How should the pedagogical approach of the GSD change in order to make space for this kind of interconnectedness?

In pedagogy, what’s important is the notion of scale. We have to challenge ourselves as an institution to work across these scales. At the small scale of the individual building, architects are limited to solving the problem by softening the threshold between components of society in order to address inclusiveness and exclusion. They can, however, decide what kinds of projects and what aspects of a project are worthy of their time and attention. At the planning and urban design scale, it’s a bit easier, as planners and urban designers necessarily have to think about multiple systems and populations. At the territorial/regional scale, the landscape architects have the greatest agency as they’re trained to look at these large terrains.

But how can we educate each beyond their own scale, so they can understand the systemic problems? How do we teach the ability to understand how these issues play at different scales? We have to recognize that we reinforce the divide when we silo these discussions in our pedagogy and public engagements. We perpetuate a problem where architects have the arrogance to work at the urban scale without understanding the inherent structural problems at that scale, and planners work on broader landscapes or territories without adequate training in those issues.

Additionally, every student brings their lived experiences and unique perspective to any discussion and it’s critical that the faculty creates safe spaces for people to share their perspectives because we have so much to learn from each other. Thus, the interconnectedness you refer to already exists, at least at the interpersonal level, and it’s really a matter of activating this more consciously in our pedagogy and in the more structural organization of the GSD.

Do you believe that a course on spatial justice should be a mandatory part of core programming? If not, what kind of restructuring to the curriculum do you think is necessary?

It’s not about making spatial justice a core class, but a matter of emphasizing core issues like race and ethnicity, economic justice, climate change, and public health and embedding them in every course—background and foreground, always omnipresent. Our responsibility as teachers is to reflect collectively on what voices we’re including, what we’re not including, and to be self-critical. That’s fundamental to how we provide alternate narratives. All GSD faculty should ask themselves, How does understanding racism inform my curriculum? What is happening in the world and why is my curriculum not responding to this condition? One must make space in the curriculum to let other voices meaningfully enter the discourse, be heard, and have a transformative effect—that is, we must open our minds to be changed by them.

I am critical of the idea of a required core class on race because it lets everyone else off the hook. Maybe it will be a good beginning, but if we can’t meaningfully embed the questions of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and ability in all our curriculum, then we might as well accept that we lack the ability to go beyond gestures and symbols to really have the courage or capacity to effect real change.

Rahul Mehrotra is professor of Urban Design and Planning and the chair of the Department of Urban Design and Planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Mehrotra is a practicing architect, urban designer, and educator. His Mumbai + Boston-based firm, RMA Architects, was founded in 1990.