The pandemic has had an immediate and tangible impact upon urban life—rewiring and, in some cases, completely transforming the daily experience of our cities. Nightclubs, concert halls, and stadiums have gathered dust since mid-March, while car-cluttered streets in city centers have transformed into pedestrianized avenues that teem with bistros and eateries. One of the most far-reaching changes has been that in a very short amount of time, our relationship to work has been completely transformed. Millions of people are suddenly working from home, which has raised many questions for the future of housing design.

“Dual-Use,” Farshid Moussavi’s current studio at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, explores the politics of designing everyday spaces in architecture and the profound impact it has on people’s lives. In an era when residential developments’ cookie-cutter formwork follows private-sector financial systems and reinforces divisions along gender and class lines, Moussavi is interested in subverting that capitalistic demand. By generating new socially inclusive and politically resilient dual-use housing typologies while still satisfying market need, Moussavi adopts an approach that is anchored in real-world problems as well as in the constraints of practice.

According to Moussavi, over the course of the pandemic, we have inadvertently traveled back through time: reverting to a preindustrial, 19th-century housing model, wherein domestic space was also the workplace. Today, office workers roll out of bed, don their work shirts, and find a flattering corner of their home to load up Zoom. A craftworker folds out a workbench from a closet in his studio apartment, while a mother feeds her baby before heading into a spare bedroom that has been repurposed as a hair salon where she receives clients. But working from home is far from a universal right; the pandemic has revealed and intensified inequalities of privilege, labor, and class as not all work can be accommodated in the standard modern apartment.

Moussavi explains that even as the pandemic has pushed to the surface the inequality embedded in the current DIY conversion of domestic space into workspace, it has also presented the idea that another world might be possible. If we abandon the live-work binary that has dictated the development of modern cities, how might new urban residential typologies be enriched with equality, diversity, and resilience and generate new forms of social capital within a truly shared experience of city life? It is an exciting and vital time.

“Generally, left-wing activists, academics, and journalists blame the housing crisis on neoliberal enterprise and the nation-state for abandoning welfare,” says Moussavi. “We need to understand the housing crisis as a typological question too—not just who delivers housing, but how it’s designed, and what can be done differently as well.”

Grounding the recent attention placed on dual-use residential architecture within the much longer history of live-work domestic spaces, this studio merges an in-depth historical survey with emerging contemporary criticism. A book identifying eight types of workers that must be taken into account with any dual-use architecture, penned by Frances Holliss, London-based architect and emeritus reader in Architecture at London Metropolitan University, will be discussed in tandem with case studies ranging from the medieval English house where farmers lived alongside their livestock to recent examples. The Mumeisha Machine in Tokyo, built in 1909, for example, features a long corridor that acts as a transition space between the public street and private residences around back, while the Maison de Verre in Paris, built in 1932, features a three-doorbell system in a doctor’s home office, with separate entrances, so that professional and personal affairs could be carried out in their own designated space.

The studio will also conduct virtual home visits with individuals representing these different home-work setups. And it will hear from architects and historians of architecture and art including Umberto Napolitano, Irénée Scalbert, and Hans Ulrich Obrist on the relationship between housing and spatial diversity, biodiversity, and user-empowerment.

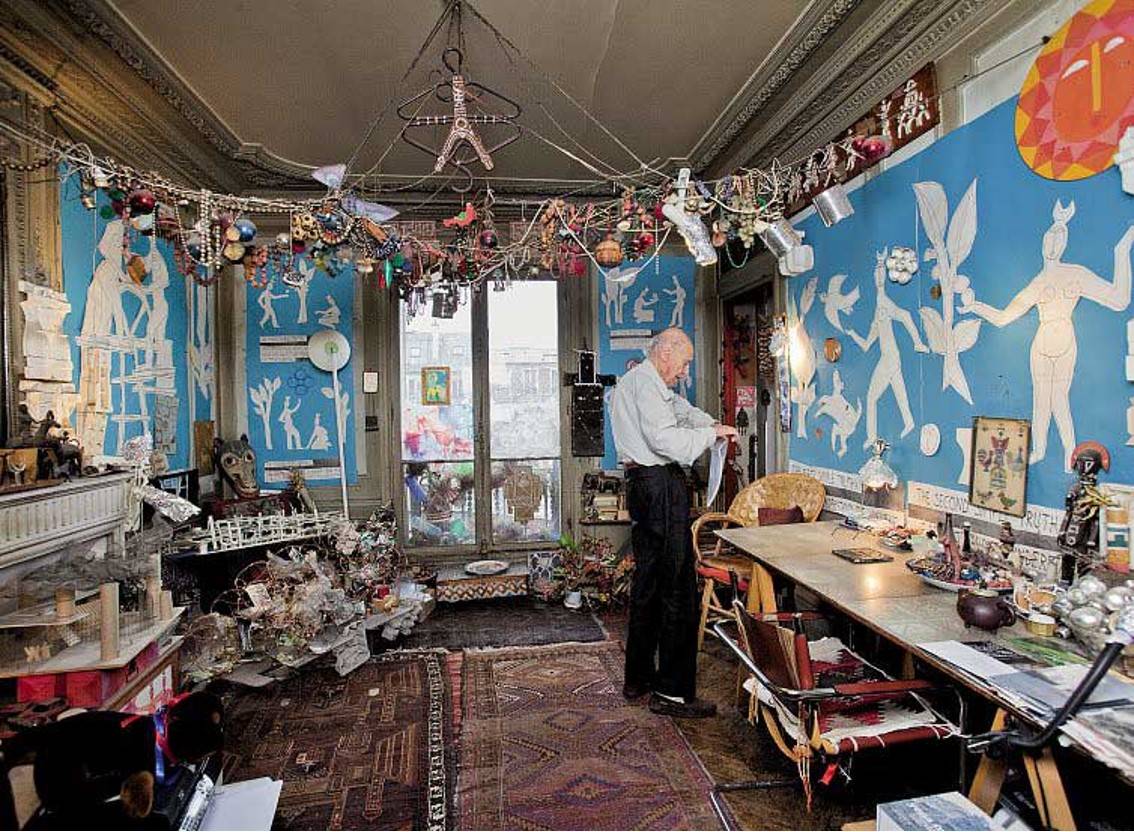

Building upon a sequence of housing studios Moussavi has taught since 2017, “Dual-Use” brings an additional protagonist—Yona Friedman—to join two French architects researched by the previous studios. The 19th-century Parisian Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s flexible block system, which was investigated in the 2017 studio, is in many ways the antithesis of Jean Renaudie’s spatially complex 20th-century residential architecture, which was investigated in the subsequent studio. In different ways, Haussmann and Renaudie sought to interconnect the design of individual dwellings and the urban space, and focused on user empowerment through the provision of spatial diversity. Yona Friedman offers an interesting comparison point, with a largely theoretical practice that was centered on ideas of self-planning and user-appropriation of space.

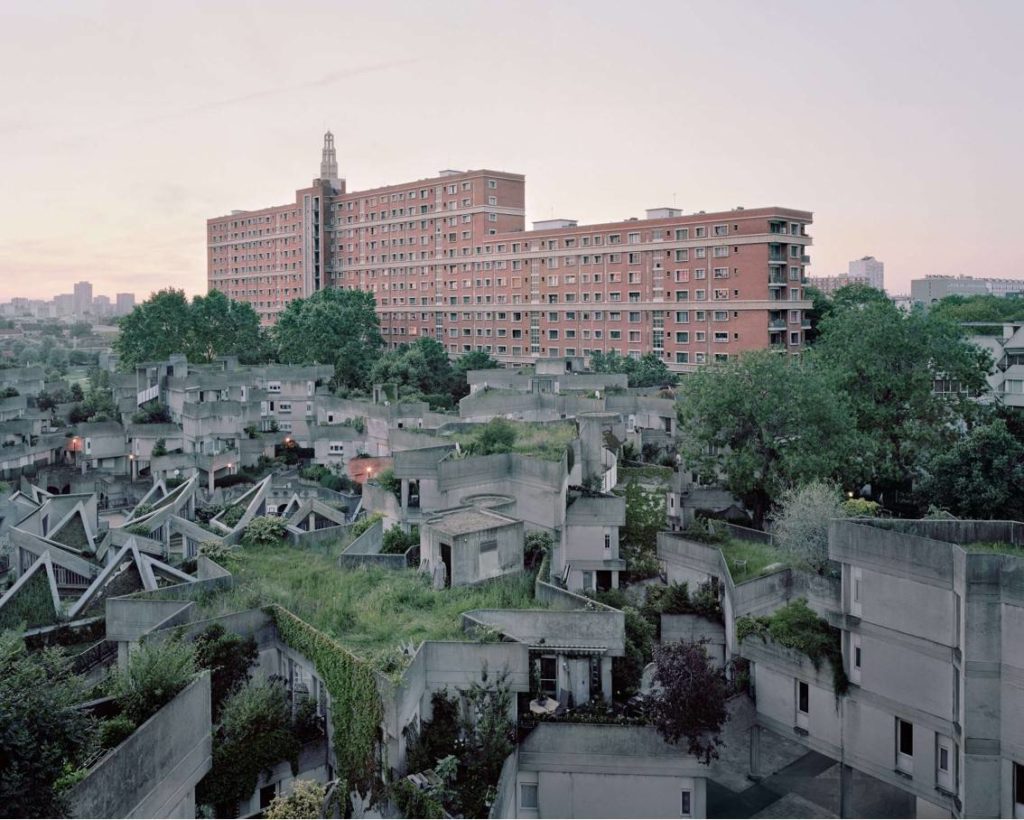

According to Moussavi, in Haussmann’s system, external consistency is king—long blocks of housing carve out the shape of the city, while the internal elements remain flexible and readily tailored for individual use. A tall lower level with ample natural light provides the perfect site for unique live-work configurations, while the block retains a uniform urban facade. Renaudie, meanwhile, takes the opposite approach in his kaleidoscopic Ivry-sur-Seine, which offers spatially unique dwellings, no two of which are identical. Garden-scale balconies spill out beyond the apartments and provide a strong connection between domestic space and the landscape, between biodiversity and well-being. Malleable space, a flexible boundary between intimacy and community, and multiple types of use are built into Renaudie’s architecture. Friedman, a contemporary of Renaudie, was largely a theorist; projects like the Flatwriter—which could ostensibly help users design their perfect apartment with the press of a button—are far more utopian, untethered to market demand.

“Haussmann begins from the collective, whereas Renaudie departs from the individual—and with a focus on biodiversity in cities, is very relevant to our concerns today,” says Moussavi. “Friedman adds that element of ambiguity. You can learn from all three of them simultaneously and find new applications for their work in the conditions of the present—that’s the beauty of having history behind you, and why I’m a huge fan of precedents.”

Students will apply their insights to these architects’ work in designing their own dual-use block in one of three sites along La Petite Ceinture—meaning “the little belt” in French—a 32-kilometer stretch of unbuilt land surrounding Paris. Containing the skeletal remains of a 19th-century railway system, the belt has become a space of wild abandon. Known as the mecca of Parisian street art, it also includes areas of slums and overgrown nature. Data from public consultations gathered by Paris Urban Agency (APUR) shows the belt’s latent potential in the city’s collective conscience: community gardens, affordable housing, and a wildlife reserve were among the suggestions raised by the public.

Based in the 16th, 13th, and 19th arrondissements, these sites vary widely in their own topographies, demographics, and the way they slot into Parisian life and culture. Moussavi explains that the 16th, known as the rich urbanites’ enclave, has the least social housing of anywhere in the capital, while the 19th—the poorest arrondissement in Paris—has the highest concentration of social housing and is the site of former refugee camps. All of the sites are elevated above or face the material ghosts of the railway. Surrounded by Haussmann blocks, parking lots, abandoned stations, and jazz clubs, these are loaded spaces, and the students will need to be surgically precise in their interventions. The future of Paris is waiting.

“We are asking the students to take a visionary position,” says Moussavi. “The pandemic has called into question the efficiency of all the old housing systems, and I think it’s up to us to produce the visions of tomorrow.” The need for alternative typologies for live-work housing is self-evident. According to a study published by the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research this summer, 42 percent of the US labor force is currently working full-time from home; this figure climbs to 52 percent in Europe, and 65 percent in the UK. Even when a vaccine is made widely available and we flatten the COVID curve for good, many Fortune 500 companies will continue to allow employees to work from home. The studio is an opportunity to rethink residential architecture and generate new typologies with dual-use apartments that are suited for a variety of households and that place individuals as well as community at their core.

As seen in the organic evolution of Renaudie’s private terraces into community gardens at the hands of its residents, it’s important for these new typologies to be adaptable: both toward their inhabitants’ fluctuating needs and for unseen future circumstances. In its capacity to incite structural change and transgress the current boundaries of architectural thinking, the pandemic is a catalyst to cross that threshold—but it shouldn’t be understood as an isolated scenario. “Architecture must not be just reactionary,” cautions Moussavi. “Genuinely equitable dual-use domestic space is not just a pandemic issue, but a matter of one’s right to a supportive live-work environment regardless of profession.” This right, and its future rewards of resilient, enlivened communities, persists far beyond the confines of any pandemic.