The term “landscape” historically referred to pictures of the world—vistas or views—and so it is only a small step to think of landscapes as portraits of society, representations of social imaginaries. What is included and excluded in these pictures is revealing. A landscape can be a tool for a designer: a mirror held up to society that exposes the distortions and repressions that underpin its self-image. In the past months and years, activists have aimed to hold up such a mirror to reveal systemic racism in America. Students, faculty, staff, and guests at the GSD have joined in and sometimes led the way. I have had the opportunity to interview several of these inspiring figures: Everett Fly, Jill Desimini, Linda Shi, David Moreno Mateos, and Kathryn Yusoff. Their viewpoints vary, but all agree that adjustments to the disciplines taught at the GSD would help in coming to terms with—and hopefully undoing—the systemic racism revealed across the American landscape.

The architect, landscape architect, and preservationist Everett Fly notes that this process begins with seeing. Fly grew up and now practices in San Antonio, Texas, a city with a palpable sense of heritage embodied in its historic architecture. San Antonio formed Fly’s sensibility, which he hopes more designers will share. “Too often, architects start with their plan by assuming that no other culture has influenced or impacted the site where they’re planning. . . . [They assume a] clean slate—as if no one had ever existed there.” But contrary examples make their way periodically into the news. In 2010 in Sugar Land, Texas, excavations for a public building project uncovered a mass gravesite containing the remains of 95 former slaves. Similar discoveries occurred in New York and Philadelphia. Important stories had been buried along with these bodies. “For too long we have lived with the assumption that there is nothing significant you need to know about African American history in the landscape,” Fly says.

Fly first came to this realization during his education as an architect. Like today, the 1970s was a period of strong social justice movements. At architecture school in Austin, Fly had few Black classmates, and he never heard professors speak about the contributions of African Americans to American architecture. When he began graduate studies at the GSD, Fly enrolled in a history course taught by J. B. Jackson, who was transforming the field of cultural landscape studies. Jackson talked about the role of Indigenous peoples and European immigrants, as well as the impact of railroads and highways within the American landscape. It was far from the clichéd notions of landscapes as merely picturesque views. Still, Jackson only mentioned African Americans a few times. With a streak of defiance, Fly set out to write a term paper on historic Black towns in the South.

By the end of a semester of intense archival work, he had amassed a few dozen brief references. Jackson took a personal interest in the project, which Fly continued into the following semester. He soon included examples scattered across the United States. Fly began sharing his findings at conferences and making contacts in historic preservation. After graduating, a year-long fellowship allowed him to visit many of these towns and go to the cartographic division of the National Archives to seek out obscure maps. “This opened up another vision for me: that you could document these places, despite what people would say, that ‘we don’t have the information’ or ‘you can’t prove that these existed,’” Fly explains. What followed has been a lifelong practice of gently asking people to look again. When greeted with “No, we don’t have anything like that,” he replies: “I bet you do, and you just don’t know how to look for it.”

Fly’s work as a preservationist came together as three components: “Being able to see the communities, being able to find the documentation, and then being able to correlate that with the formal discipline of historic preservation.” This work is as important now as ever. Take cemeteries. Because of discrimination, African Americans were often turned away from public cemeteries, and burials had to take place on private land at some distance from where people lived. These small private cemeteries—”some of our most treasured and valuable sacred places”—are threatened by their obscurity. The first step is to know they exist, then to document them, and finally to engage the mechanisms of historic preservation. Similar to graveyards, early structures such as schoolhouses and churches were built by African American tradespeople rather than architects because pathways to licensure were not available. Seeing and valuing them means also valorizing a thread of African American cultural heritage. “We’re not just protecting the physical structure,” Fly says, “we’re also protecting the legacy of the trades.”

Fly urges more young designers to take an interest in the forgotten cultural heritage that can be revealed across the American landscape. He says that this work begins by always asking the client a question: “How much research have you done ‘below the surface,’ into the layers of history—who lived on this place before today, and how did they live here?” In Fly’s experience, a client will often say that they haven’t done any research. That leaves it up to designers to uncover traces that can be used to “enhance the richness of your design, and help educate your client and the users of the site.” Drawing out more layers adds richness to the picture a landscape presents.

Sometimes whole other types of sites become visible when a landscape is critically reexamined. Jill Desimini, an associate professor of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, is a champion of vacant lots. Although they are relatively rare in the centers of growing cities, in parts of other cities—Detroit, for example—vacant lots predominate. Desimini emphasizes that this is not a neutral result of market forces, but a dynamic that plays out in countless decisions that are often biased in unacknowledged ways by race and the perceived value of land. “You see aggregations of vacant land in places where residents are people of color, where people are impoverished, where toxicity levels are high due to past decisions, where predatory lending prevails, and where there is a lack of access to resources and services,” she says.

Cities prefer the easy solution of selling land to generate tax revenue. Desimini suggests exploring pathways for “returning land to the neighborhood.” This is not as simple as it sounds—it is a process that must be envisioned and designed. Desimini is currently teaching “From Fallow: Equitable Futures for Landscapes of Injustice,” a seminar at GSD that “partners with a few progressive organizations that care for vacant property.” She says that the open-ended nature of studio research is an asset: “It is a matter not so much of making drastic change to the sites themselves, as drastically reimagining how we approach them.”

Beyond her seminar, Desimini’s larger project involves changing the way landscape architects work. Her books, Cartographic Grounds: Projecting the Landscape Imaginary (with Charles Waldheim) and From Fallow: 100 Ideas for Abandoned Urban Landscapes, are both invaluable resources. Investigation, drawing out possibilities, publishing, and conversation can have a dramatic impact on the course of a discipline. She explains, “I think that we need to be less fickle and faddish and work on projects for a long time and in places for a long time. It is hard to sustain the interest, but I think that it is necessary to build trust.” To undo systemic injustices in the American landscape, a sustained systemic response is necessary.

Linda Shi, an assistant professor at Cornell’s department of City and Regional Planning, has come to a similar conclusion but from a different direction. As an expert on urban environmental governance, Shi examines and suggests planning policies for addressing climate change while simultaneously improving social equity. Her studies are capacious, with titles such as “Explaining Progress in Climate Adaptation Planning across 156 U.S. Municipalities.” But they are rooted in careful investigations of local policies—for example, a series of resilience action plans for Boston.

Shi’s focus on policies is unfamiliar to most designers: “In planning, the things we often trade in are papers and books” rather than in projects and precedents. Landscapes are shaped by policies, but planning and design “often happen in the absence of a consideration of policy and other realities that constrain action,” she says. Imagine, for example, a project to build a new park in a low-income neighborhood. It seems good—an amenity for the community. But if a parcel of land becomes a park, it will not be generating property taxes. And who will use the amenity? If designs do not account for policy structures, the market will take over and “do what it does, which is gentrify.” The park may ultimately exacerbate inequities by driving up housing costs. Shi suggests applying the design imaginary to the policy sphere: “a combination of policy and design, rather than the two being separate.”

She began working on issues of equity and justice from a background in environmental management. While working for AECOM, Cambridge-based I2UD, and elsewhere, she realized that, in practice, environmental governance is “all about social issues and the rural-urban relationship.” Shi enrolled in a planning doctoral program and was particularly moved by class taught by Neil Brenner and Diane Davis that gave her a theoretical lens on what was happening and her role in it. She finds this perspective crucial: “Planners, as much as architects, need more reflexive thinking about our roles in our projects and how we embed a concern for justice in our work.”

One path for change may come from outside the core disciplines of the GSD. David Moreno Mateos, an assistant professor of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, is a restoration ecologist—which is to say, he is a scientist. Moreno Mateos teaches “Ecosystem Restoration,” “Climate by Design,” and, this semester, “Re-Wilding Harvard.” This most recent seminar stems from a radical proposal to return Harvard’s landscape to a condition of wilderness. For now, Harvard has only offered a small plot for experimentation, but what is important for the seminar is not the scale, but the vision. Imagining landscapes without humans is a useful thought experiment for designers who ought to be able to justify the human control their projects require. Moreno Mateos has worked on much larger sites that have been severely degraded by human activity, including Southwest Greenland, where Norse sites have been recovering for more than 650 years. For the Harvard site, Moreno Mateos notes that “Lawn, from a biodiversity perspective, is green cement.” A wild landscape is one that can function on its own, and it is a bold claim that functional wilderness can be re-created even in the middle of Cambridge.

According to Moreno Mateos, part of the process of re-wilding Harvard is to “learn from how people were using the land before European settlement.” Different human groups have had differing power to transform landscapes. The Indigenous peoples of North America had their own impact, causing 95 percent of megafauna on the continent to go extinct over a period of thousands of years. European colonists caused fewer extinctions, but their impact was larger and more temporally concentrated. Human-caused ecological changes are ongoing: with vastly fewer buffalo, for example, forests are now expanding into the Great Plains. The idea is not to assign blame or to return to an imagined idyllic state, Moreno Mateos says, but to see that as one culture displaces another, ways of viewing the land also shift. Now more than ever “we have entirely domesticated landscapes that are not real.”

Moreno Mateos’s work suggests a certain type of environmental justice: “the right of species to live in the place where they used to be.” The first step, he says, is to “understand what an ecosystem actually is,” how it operates, how it responds to human impact, and how it can recover from them. From there, landscape architects may be in positions to use design to help these processes to happen, working with clients on specific sites. And even with wilderness, human involvement is crucial: “You need to listen to people. You need the people who live with an ecosystem to be part of it. Otherwise it’s going to fail,” he explains.

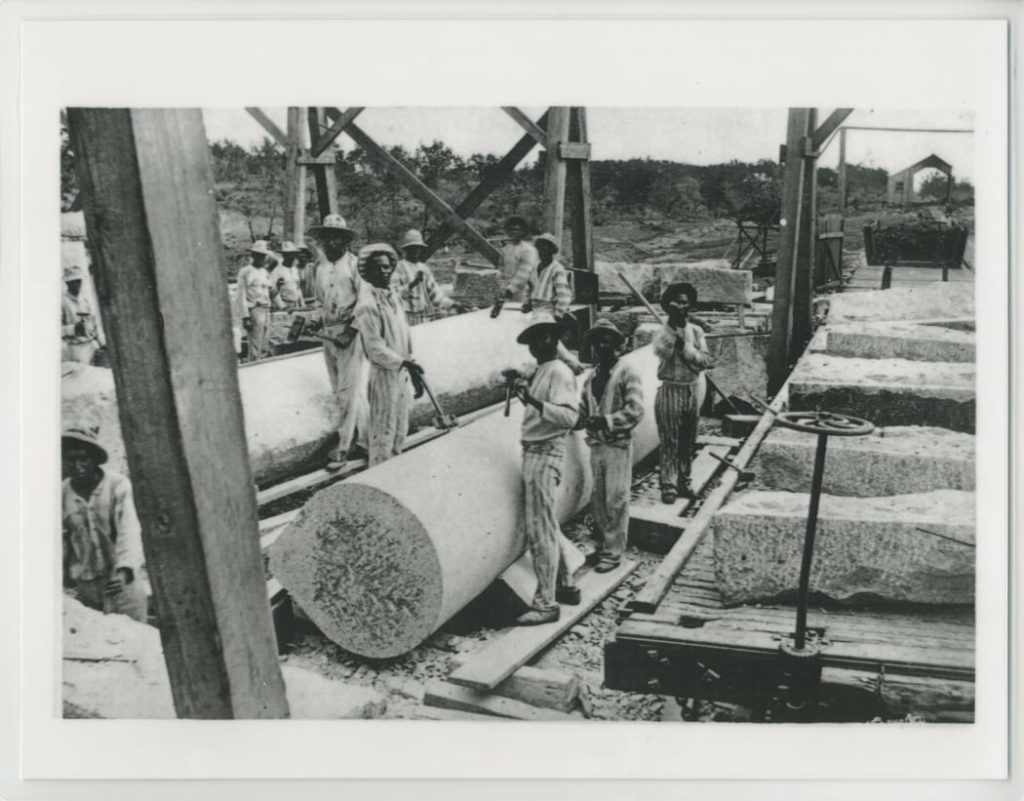

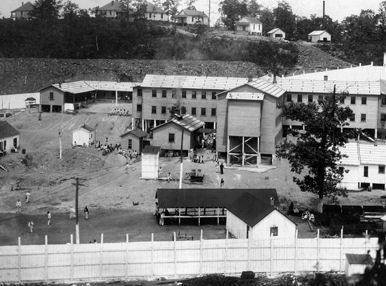

Of all those I interviewed, Kathryn Yusoff offers perhaps the widest lens in generating a picture of the interrelationship of race and landscape. Yusoff holds the unusual title of Professor of Inhuman Geography at Queen Mary University of London. The cases she brings to the table defy reduction. She gives me an example: “Convict-lease prisons in Alabama were built at the entrance to mines. These prisons were filled with Black men and boys that were literally kidnapped from social space to enter a legal system that systemically punished Blackness, while simultaneously co-opting Black life to corporations as a ‘resource’ for industrialization. Convicts were sent to mine coal and work in the iron ore furnaces. So, there is a very clear connection between what goes up, in terms of the buildings of modernity in the ‘Magic City’ of Birmingham, Alabama and the shares in northern stock exchanges, and who goes down into the underground. This landscape of racial capitalism both met the political ambitions of white supremacy by suppressing the Black vote and materially built the post-plantation urban landscapes through another form of Black subjugation.”

How to untangle this complex nexus and engage with it as designers? For Yusoff, the first step is to shift what is taken as the object of design. “There is a tendency to assume that the built environment is the primary space of consideration, whereas I would like to disassemble that ‘autonomy’ and have us think with a broader set of relations of the un-architectural or what might be called the subterranean architectures of spatial practices.” If buildings and landscapes present flattering pictures of a simple and tidy social order, a little excavation will uncover a vast network of lives that have been repressed. “What are the racial undergrounds that enable the verticality of the city, its flows, and material connectivity?” she asks.

Yusoff’s work upends key concepts that are in danger of becoming platitudes. In response to the vogue for the Anthropocene (a term that refers to the current geological period, in which humans are having a definite geological impact), Yusoff demands “a billion Black anthropocenes, or none.” The life and perspective of each Black body that has made “the Anthropocene” happen must not be forgotten under the rubric of such a wide and abstract term. “These are the billion life-worlds of Indigenous and Black peoples that colonialism attempted but failed to extinguish,” she says.

Yusoff’s project is big, and its implications are daunting. “This is a transnational and planetary affair and involves confrontations with the histories of settler colonialism, neo-extractivism, and the normative understandings of matter itself.” For designers, aesthetics—how things look—may be the most accessible aspect of Yusoff’s work. She recasts aesthetics as political: “Political aesthetics is a way to think through the aesthetic-as-always-implicated in the construction of sense and sensibility, which is more than a question of feeling. I think about these arrangements of sense as a ‘affectual architectures’” Telling a story, painting a picture, or constructing a landscape is a political act. “We can see any mapping of planetary origins as a world-building praxis, where people and places get framed in certain ways.” One task for social justice, then, is to pay attention to the “strata of peoples that underpin planetary transformation and are pressed closer to its harms.”

However landscapes are understood, seeking justice within them cannot be a simple affair. Engaging with a functioning ecosystem within a cultural landscape and within a democratic society should be viewed as an ongoing process. This engagement involves actively studying—and imagining—what landscapes are, and what they can be. Only then can we begin projecting a better world onto them.