Euro-American conceptions of the future often disregard the past—or, worse, reject it. From the Bauhaus to contemporary techno-utopianism, novelty continually underpins the dreams of what could be, particularly those dreams proclaimed by architecture’s loudest voices. The 18th Venice Architecture Biennale—on view through November 26 and featuring a range of work by students, alumni, faculty, and affiliates of the Harvard Graduate School of Design—does not condemn these efforts; rather, the exhibitions and national pavilions imply that such visions are impoverished because they are amnesic. We must not build for tomorrow without understanding and acknowledging all that came before—a position that many less-lauded practitioners globally have long championed.

Memory is one of the strongest, if not often explicitly stated, topics of this Biennale, curated by Ghanian-Scottish architect, academic, and novelist Lesley Lokko. Counterintuitively titled The Laboratory of the Future, the exhibition focuses less on showcasing models of what will be and more on the foundational material and conceptual conditions from which structures arise, from the transnational extraction of minerals on which projects like New York City’s Hudson Yards development depend to a display of the banal correspondence that all building projects and exhibitions such as this require. Process is privileged over product. Totemic structures, which loudly declare singular futures, are replaced by displays of vast archives, such as a collection of every issue of The Funambulist. Studio workshops occupy a cavernous room in the Arsenale as if in situ, messy and overstuffed. These rich displays’ too-muchness suggests multiple paths forward rather than didactic solutions. As a result, the conversations Lokko convenes equalize the exhibition’s participants. In particular, those from Africa and the African diaspora, women, and younger practitioners are treated as prominently as those architects whose names typically dominate the most prestigious architecture competitions, festivals, and building contracts.

Many projects highlight instances of success without singular architects. The Ecuador-based design agency Estudio A0, whose co-principal Ana María Durán Calisto (Loeb Fellow ’11) has served as Design Critic in Urban Planning and Design at the GSD, challenge colonial narratives of “primitive” Amazonian cities in Surfacing–The Civilized Agroecological Forests of Amazonia. Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technology used for gold prospecting helped produce maps of 26 ancient urban areas, which featured waterways, suburbs, and other complex structures.

These discoveries reject notions that the forest was entirely “wild” and indicate that inhabitants of the Amazon River basin had both advanced understandings of their natural surroundings and the ability to shape them. Woven tapestries (a recurring mode of expression throughout the Biennale) depict imagined representations of life and the built environment in these cities, which in turn make material the interlocking nature of the urban and ecological.

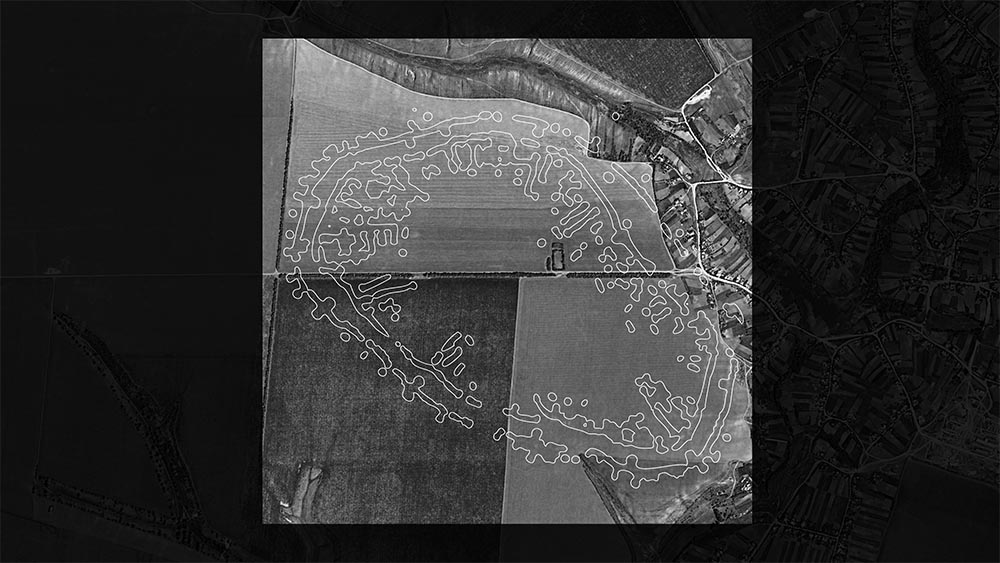

The earth again acts as a depository of novel notions of the city in The Nebelivka Hypothesis, presented by David Wengrow and Eyal Weizman with Forensic Architecture and the Nebelivka Project. Eleven settlements from 6000 years ago, each with domestic buildings built in a ring encompassing a vast open area, were discovered in central Ukraine using modern archaeological technology. What the curators describe as the “centerless” configuration of Nebelivka is not just a banal characteristic. “No evidence of palaces, central storage, administration, rich burials, nor any other signs of top-down control” were found in excavations, the presentation details—a discovery that contradicts the early scholarly consensus that cities require “hierarchical form and structure.” Additional evidence was found that inhabitants’ farming had a gentle relationship with the surrounding land. This relates to the area’s chernozem, a remarkably rich soil, which the researchers argue may not have arisen by chance. It may be anthrosol—soil formed through human activity—which could demonstrate that cities can not only sustain but improve ecological health.

High-tech research is not required in order to learn from the past, though. The Slovenia Pavilion’s exhibition, +/-1 °C: In Search of Well-Tempered Architecture, goes so far as to criticize high-tech intervention in solving ecological concerns. Rather than dismiss vernacular buildings as charming ethnographic curiosities, curators Jure Grohar, Eva Gusel, Maša Mertelj, Anja Vidic, and Matic Vrabič showcase dozens of traditional buildings that are remarkably energy efficient architecturally, without requiring complex engineering solutions hidden behind walls. The exhibition implies that learning from these structures is not an issue of embracing nostalgia but rather common sense, as myriad solutions to regulating building temperatures already exist: the central stove that dried clothes, cooked food, and served as a gathering space for sleep and sociality in Slovenian homes; micro-sleeping cells in German cottages that could be closed and heated by an individual’s own body heat; a smaller room for social activities within Slovenian huts that could be heated separately from the pantry and the other less-used spaces surrounding it.

Edgar’s Sheds, an installation by GSD Assistant Professor of Architecture Sean Canty and his firm, Studio Sean Canty, also celebrates the vernacular. It features a fragmentary and poetic reconstruction of two sheds built by his great-grandfather Edgar in Eliott, South Carolina, enacting what Canty calls “retroactive reproduction.” The partial buildings “draw attention to the holes and ruptures of our collective history of black experience,” he writes, which is “a direct consequence of slavery.”

In each of these examples, and throughout much of the Biennale, the definition of “architect” is challenged. There is no single mind to whose genius these vernacular innovations can be attributed, for example.

Recognition instead must go to collective memory, which the Great Britain Pavilion designates a space maker in its own right. Curated by Joseph Zeal-Henry (Loeb Fellow ’24), Jayden Ali, Meneesha Kellay, and Sumitra Upham, Dancing Before the Moon argues that ritual practices, which depend on sustained and embodied collective memory, act as “spatial portals.” The artworks on display address hybrid identities in their reflections on rituals both ancestral and contemporary. Monumental vessels by Jayden Ali evoke Cypriot cuisine and Trinidadian steel-pan bands. Mac Collins’s abstract sculpture made of ebonized ash timber, at once anthropomorphic and otherworldly, celebrates the dominoes popular amongst British Jamaicans.

For diaspora communities especially, cooking, music, games, and similar actives help dissolve distance and time, bridging international borders psychically and collapsing temporalities. “They rethink the past and imagine alternative futures where architecture is agile and spontaneous and communities are bound together by social (rather than economic) practices,” the curators assert in their introduction. To dismiss these ritual participants as non-architects is in turn to delimit the possibilities of how space is understood and who has the authority to claim as well as design for it.

In striving to define new futures, the Biennale foregrounds a history in which too many voices have been dismissed and too many details about both the births and deaths of built spaces have been cast aside. Even the awards at the Bienniale sought to address this past occlusion, including Nigerian architect Demas Nwoko’s Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. Despite designing “forerunners of the sustainable, resource-mindful and culturally authentic forms of expression now sweeping across the African continent—and the globe,” Lokko writes, Nwoko remains “largely unknown, even at home.”

The casting aside of whole populations is reflected in Synthetic Landscapes, a project by Stephanie Hankey, Michael Uwemedimo and Jordan Weber (all Loeb Fellows ’22) that details the violent extraction of oil near the Niger Delta. Chevron and other oil companies’ interventions in Nigeria have forever changed the local ecosystem, destroying villages as well as the natural environment. The carbonized soil that resulted from this ecological violence “cannot be remediated, only removed, contained, moved and moved again,” writes the team, who illustrate this by using this soil itself in the exhibition’s floor. The act is a physical reminder of a warning from Amitav Ghosh about how we consider the past, which the trio quotes: “Those at the margins are now the first to experience the future that awaits all of us.”

The need to acknowledge those too-long disregarded is also poignantly addressed in unknown, unknown, an installation by Eric Howëler (Associate Professor in Architecture at the GSD), Mabel O. Wilson, and J. Meejin Yoon (MAUD ’97). The multifaceted immersive work arises from Höweler+Yoon’s Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia, which opened in 2020. It commemorates the approximately 4000 enslaved peoples on whose labor the university was dependent from 1817 to 1865. Rather than honor the dead in stereotypical monumental forms such as sculptures, the work makes visible these men and women’s erasure and their lack of recorded identities. Videos illustrate the scale of this violence by depicting a list of their limited descriptors, recorded in ledgers and similar archival materials, such as “Peter, Unknown,” “Runaway, Unknown,” and “Unknown, Unknown.” This is in turn accompanied by a recitation of these “names,” read in part by three of their descendants. The exhibition is made even more haptic by the projection surfaces themselves: muslin sheets hanging from the ceiling, which specifically reference the cotton-centric labor forced upon this enslaved population.

As these and the majority of the projects on display in Venice emphasize, the question of the future must not remain the restricted domain of only a few architects’ fantastical speculations. Rather than provide solutions, this Biennale instead strives to engrain a basic understanding of how to answer the question at all. It does not ask us to stop dreaming. It merely proposes that in order for dreaming to succeed, we must first understand who designs, who builds, and how the materials they use affect us all.