As we continue to face the twin crises of rapidly accelerating climate change and biodiversity loss, city leaders and city residents are especially feeling the heat. The increasingly desperate need to radically cool cities is becoming widespread news, and the appointment of chief heat officers in cities as widespread as Athens, Miami, and Freeport, Sierra Leone, is a testament to the urgency of the issue. Many factors contribute to both the climatic challenges and the loss of biodiversity in cities (including, simply, the construction of buildings and streets), but one solution stands out: trees.

Trees are known for their inherent ability to provide shade, and therefore to cool the environment. In many cities generally, and especially in urban neighborhoods with predominantly Black, Brown, multi-ethnic, and socially vulnerable communities, the pervasive lack of a healthy tree canopy contributes to soaring temperatures and negative public health outcomes. This is just another way in which lower income, racially and ethnically diverse communities (often referred to as “environmental justice communities”) are impacted more significantly by the multiple effects of climate change.

The absence of trees also contributes to an increasing loss of ecosystem biodiversity and wildlife habitat, which in turn has detrimental effects on the environment as a whole (both in cities and beyond). And, with few or no trees in urban spaces, we reduce the opportunity to sequester carbon, to clean the air and the soil, to mitigate stormwater flooding, and to sustain healthy habitats for birds and other creatures–all critical functions of trees in healthy ecosystems–thereby exacerbating both the effects of climate change and the impacts of social and racial inequities.

Boston and Cambridge, along with many cities around the world, have recently developed their own urban forestry master plans to reverse these negative effects. They are creating new urban forestry divisions and leadership that will oversee implementation–including both care of existing trees and cultivation of an expanded tree canopy specifically adapted to tough urban environments. In many other places, like Los Angeles, city governments are partnering with educational institutions, non-profit organizations, and professionals to develop metrics-based, neighborhood-specific plans for the most impacted communities, from both environmental and social standpoints. In Dallas–Fort Worth, the non-profit group Texas Tree Foundation has been raising philanthropic dollars to fund and oversee the installation of tree plantings, advise on urban forestry plans in various cities in the region, and set up new training opportunities in the green labor force for those coming out of prison and looking to gain new skills and move on with their lives. Additionally, new “microforestry” efforts (also known as Miyawaki Forests) that dramatically increase species biodiversity in very small urban footprints are finally making their way from around the world into American cities and even into news coverage by the New York Times.

Most recently, as of the last week in September, Cambridge has its first urban forestry demonstration project at Triangle Park, in the Kendall Square neighborhood. The project is one of three small urban parks–two on “leftover” or underutilized parcels of land–that is meant to dramatically increase the amount and type of open space available to residents and workers in this part of the City. (My firm, Stoss Landscape Urbanism, was commissioned in 2016 to design both Triangle Park and the nearby Binney Street Park, which will open in 2024 as a park for dogs and people, while another Cambridge firm, MVVA, was commissioned to design the third park, Toomey Park, as a community gathering space and play area). Triangle Park in particular, was designated to embody the principles of the City’s urban forestry plan–in part as a test, in part as a demonstration–of this new commitment to trees, biodiversity, and innovative maintenance techniques tailored to this new mission.

“The design of this project was guided by the City’s Urban Forest Master Plan and includes significant tree plantings and canopy growth in the Kendall Square area,” said Public Works Commissioner Kathy Watkins. “It also allowed us to try some new approaches for how we think about open spaces and planting trees in the City. As the trees and plantings grow in over time, this unique park will provide an incredible shaded space in the heart of Kendall Square for residents and visitors to enjoy.”

The site itself is small (three-quarters of an acre) but complex. At various times in his history, it was a tidal mud flat at the mouth of the Charles River, a fueling station, a parking lot for trucks, a dumping ground for urban debris, and an empty traffic island. It continues to be surrounded on all three sides by vehicular traffic–to the east and north by busy and noisy four-lane arterials, and to the west by a smaller connector street with an active retail/restaurant frontage. All this presented a series of challenges for transforming a compacted site with urban fill and contaminated waste to a healthy and thriving ecosystem that could support the growth of trees, shrubs, and groundcovers, and become the new center of the nearby community. These are challenges that were ultimately overcome by an extensive and collaborative team comprised of landscape architects, ecologists, arborists, maintenance specialists, environmental engineers, and others that are a combination of both city staff and hired consultants.

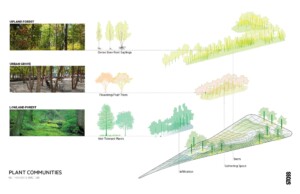

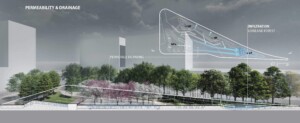

The design responds to these conditions and seeks to create a new space for trees and people to intermingle in a dense urban neighborhood. A berm along the eastern edge of the park marks the eastern edge of the site and screens the traffic and noise from Edwin Land Boulevard, allowing for elevational differences that enhance both social and environmental opportunities. On the back and top, it is planted with a variety of native upland trees and plant species (shagbark hickory, black oak, hackberry) in dense thickets that are designed to grow rapidly and to allow for natural competition and succession–an innovation in urban parks like this, one that requires an intense level of ongoing care and maintenance for which the City has committed resources and expertise. The inner side of the berm is inscribed with terraced lawns and linear seating walls, creating a welcoming and active social edge at the heart of the space–perfect for socializing, sunning, or reading. On the north, a lawn slope and stage are backed by woodland varieties and border forest floor (including American hornbeam, American smoketree, arborvitae, Eastern hayscented fern); these, too, screen out some of the noise and visuals of the nearby traffic but also create distance from the street to allow for more casual sunning, play, and performance activities. The very south end of the site–where the triangle comes to a very sharp and dramatic point, the earth is excavated to collect the site’s stormwater (a kind of green infrastructure stormwater “sponge”) and is overplanted as a lowland forest of Dawn Redwoods and a variety of birch species with an understory of ferns and witch-hazel. This feature even twenty years ago would have been non-existent, as conventional engineering techniques would have relied on pipes and infrastructure to flush the water away; here, instead, we deliberately retain the water on site into order to create ecological diversity and an environmentally healthy space. Finally, the central plaza–designed with a dramatic but abstracted parquet floor motif and rendered in white and black gravel–is populated with a combination of multi-stem River Birch and Kentucky Coffeetrees, which will provide a unique and richly shaded and flexible setting for people on scattered cafe table and chairs.

In all, the park includes almost 400 new tree plantings and introduces 15 new tree species to the collection of eight trees and four species already on site. This is quite remarkable on a site that measures just over three-quarters of an acre with a variety of spaces reserved for people and activities!

In a burgeoning neighborhood with very low levels of open space and urban canopy, this small city forest is impactful–and the social and environmental benefits will continue to grow and intensify over time, just as the trees themselves grow and take on wonderful shapes and characters. Equally important as these direct effects, the project is intended to serve as a test case and model for how the City of Cambridge implements its Urban Forestry Plan–and how cities across the country and around the world can benefit from what we learn moving forward. More tests and demonstrations like this are needed–so that we can collectively see how these projects mitigate and reverse the effects of climate change and biodiversity loss we are seeing now–and how cities can re-tool their own staffs and maintenance practices in order to better cultivate and care for these leading-edge, research-in-practice projects.