For almost two decades, Sarah Oppenheimer has investigated the conditions that enable us to act upon and recondition the built environment. The artist is best known for her dynamic architectural interventions, or more precisely, insertions, as her work tends toward partial modifications rather than total disruptions in the structural fabric of a given space.

In spring 2024, Oppenheimer was a design critic in architecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD), where she led O(perating) S(ystem)1.1, an advanced research seminar in the Mediums domain of the Master in Design Studies (MDes) program. Though Oppenheimer’s work is insistently analogue, the students in OS1.1 modified the interior lighting of the GSD’s Gund Hall with digital and wireless means to relay haptic, kinetic, and visual information across a site-specific, networked system. Nonetheless, the course was directly informed by many tendencies that have long been consistent throughout Oppenheimer’s practice, even as they have evolved over distinct periods.

In an early work titled 610-3365 (2008), permanently installed at the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh, a vista of an area immediately outside the museum appears embedded into the gallery floor on the fourth level of the building. An elongated, narrow aperture opens into a plywood tunnel, the smaller end of which is placed inside a window frame on the third floor. Downstairs, one can experience the work as a sculptural volume: an oblique, truncated pyramid with smoothed edges descending from a “wormhole” in the ceiling, as Oppenheimer refers to it. The “existing architecture,” listed on the work’s label as a medium, is indivisible from the work itself. However, back on the upper level, the acute perspective resulting from the cone-like design is offset and virtually flattened by the optical effect of two pairs of diverging grooves carved along the structure’s interior, flanking the openings at both ends, while the ultra-Eamesian curvatures of the form also help to minimize sharp shadows. This sleek viewing device offers a crisp but disorienting image that equally adheres to the logics of immediacy and hypermediacy, rearticulating the perception of proximity between interior and exterior spaces.

Currently on long-term view at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), S-334473 (2019) is exemplary of another well-known series of Oppenheimer’s works. An iteration of an earlier project titled S-337473 (2017), exhibited at the Ohio University’s Wexner Center for the Arts, the MASS MoCA work consists of a pair of interactive, kinetic sculptures grafted onto the existing architecture. Visitors can rotate and reorient the sculptures along a predetermined arc. Each device features a beam made of glass and black steel that can pivot around the 45-degree axis of a slanted pole. When turned vertical, the beam stands parallel to the columns in the space; it aligns with the wooden ceiling joists when turned horizontal. The instrument’s structural support and rotary actuator are revealed on the gallery floor above, at the other end of the rotational axis that extends through the ceiling. Such instruments are like “conduits for energy transmission,” Oppenheimer says. Activating the devices with their movements, audience members experience the environment through the lens of transient images framed by the machine’s choreography and reflected in its surfaces.

While Oppenheimer’s work might readily recall the aesthetics of Lygia Clark, Nancy Holt, or Daniel Libeskind, she also points out resonances between her practice and that of Christo and Jeanne-Claude. The duo’s monumental wrapping of iconic buildings with temporary structures made of fabric was always accompanied by an archive documenting a bureaucratic trail, the process of negotiations with implicit yet all-too-present policies and protocols. For Oppenheimer, Christo and Jean-Claude’s temporary overlays can, in fact, foreground a sense of touch by other means, a kind of sociality that exceeds or extends the limits of haptic grip or optical grasp.

Particularly important for Oppenheimer is “grasping what systems already exist before we start thinking about the overlay of another system,” that is, before the so-called design process begins. In fall 2023, Oppenheimer was an artist-in-residence at the Laboratory of Intelligent Systems at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL), an experienced that expanded the scope of her thinking about how exactly change takes place within an environment. Through studies that include edible robotics and autonomous ornithopters, researchers at EPFL aim to develop task-based technologies that can be integrated with the dynamics of an existing organic system. “Once the organism is reframed as a locus of emergent and adaptive patterns rather than a closed-off thing, a robot would no longer need to mimic an object per se,” Oppenheimer explains, “but learn the living entity’s way of existing in its larger social network.” Developing this interest in larger social and biological systems, she has sought deeper and more dynamic insertions into the existing architecture or, more precisely, orchestrations of evolving architectonic ensembles.

Exhibited at von Bartha gallery in Basel, N-02 (2022) is a more recent piece that incorporates several interlinked elements in motion. Visitors could activate an expansive pulley system by sliding horizontal black bars attached to custom-made freestanding walls, adjusting the vertical position of several rows of linear lighting fixtures hanging from the ceiling. A change in one corner of the room could trigger effects of different degrees elsewhere, allowing for several trajectories of causation to be possibly traced between what seem like inputs and outputs. The shifting reflections of the luminescent strips in the glass facade of the gallery—which sits in a converted garage with an active gas station still outside—marks yet another layer of change in one’s environmental perception when looking out from the inside.

Given the largely infrastructural and therefore hidden underpinnings of a lighting system, N-02 and related projects highlight the relationship between what meets the eye, what can be touched, and what can be sensed and identified as a mechanism of change in the environment. Light is here both a medium and a metaphor for the “perceptibility of cause and effect,” as Oppenheimer puts it, “because if something cannot be sensed, visually or otherwise, then it can hardly figure in our understanding of causation at all.”

Many of these ideas set the scope for OS1.1. The seminar aimed to experiment with lighting hardware to redirect sensory registers. “Illumination blurs a building’s boundaries,” reads the course description. The Gund Hall lobby served as the main site of exploration, where students conducted light systems analysis, surveys of wiring diagrams, studies of reflectivity on different surfaces, research into the legal limits of occupation, as well as interviews and walkthroughs with the facilities staff and regular occupants of the space. With backgrounds ranging from media arts to computational and industrial design, the students brought their expertise in programming, modeling, and fabricating, among others, to bear on the principle of adaptation. Seminary participants designed several prototypes with each iteration exploring reciprocities between bodily gestures, environmental perception, and the rhythms of machinic modulation.

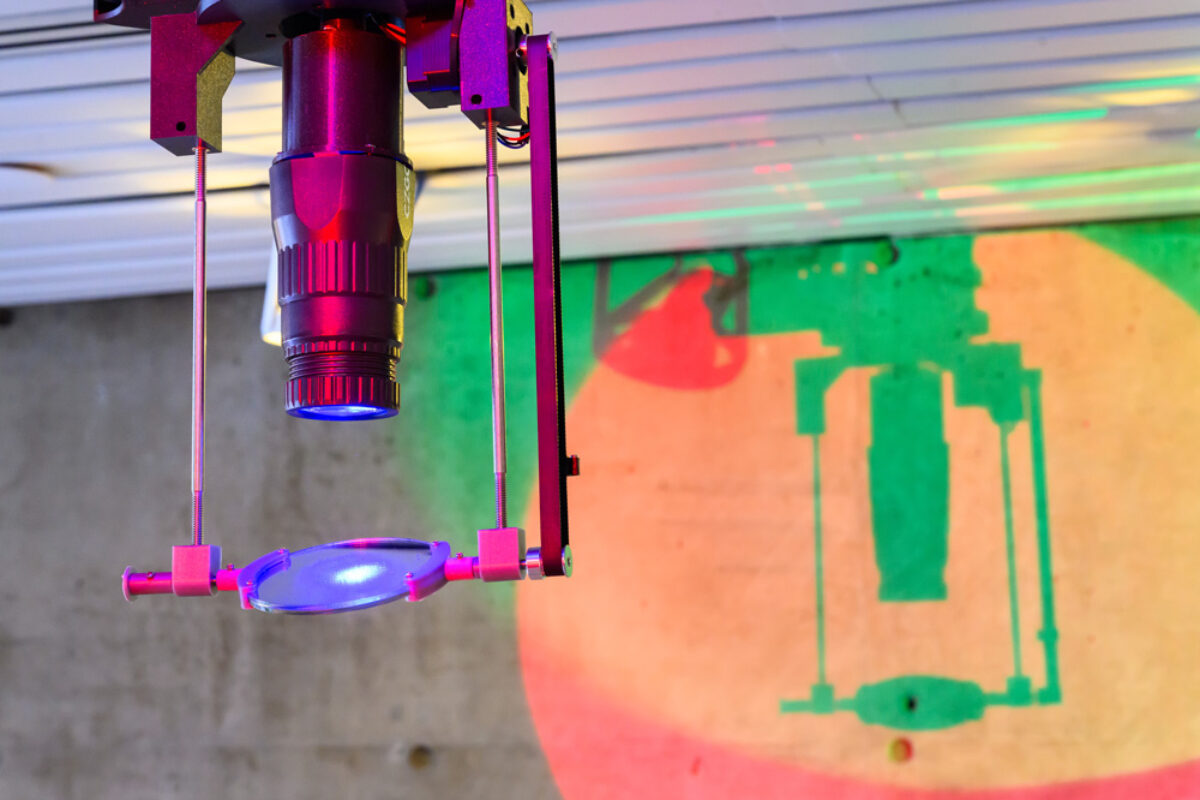

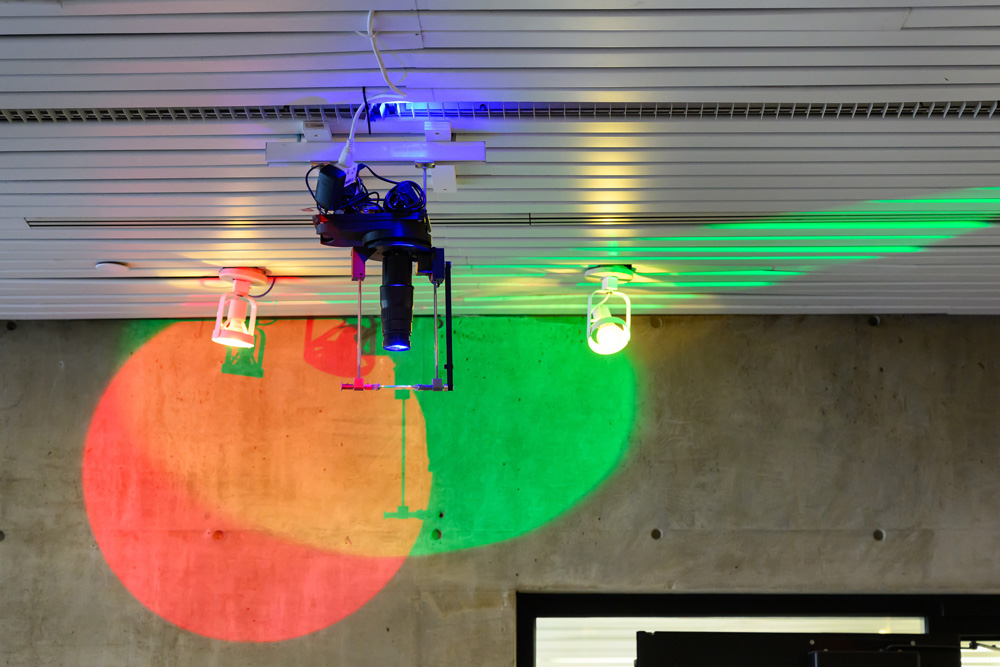

The final exhibition of student works includes a collectively designed kinesthetic ensemble. Three wooden rings affixed around one of the columns in the Druker Design Gallery control three bespoke spotlight fixtures lodged into the ceiling, each with a rotating reflector. Each ring, which Kai Zhang (MDes Mediums ’24) refers to as an “architectural knob,” is equipped with optical sensors, an RGB color strip, and ball bearings. By turning a ring in one or the other direction, one could adjust the x-coordinates of one mirror and the y-coordinates of another, moving and modulating the three spots of red, green, and blue across the space.

Technically, the system resembles the inner workings of projectors and 3D printers that use movable micromirrors to control the direction of light beams. As one of the group’s guiding observations, this was suggested by Quincy Kuang (MDes Mediums ’24), who brought professional experience in the Digital Light Processing (DLP) industry. Conceptually, the comparison also indicates the project’s attempt to reframe images and objects as gestures with reprogrammable contours and coordiantes. OS1.1 developed as Oppenheimer’s own focus in recent years has shifted away from what she calls an “object-oriented” approach. She has become increasingly interested in questioning “how we could set in motion something whose gestalt cannot be seen as an enclosed totality; how we could sense linkages or effects of linkage across spatial gaps.”

On the note of filling in the gaps, Kuang’s personal residence, only a stone’s throw from the Gund, also remained accessible to everyone in the class to use as an invaluable, shared studio and fabrication lab. After all, experimentation with the variable materialities and mechanics of common spaces can itself serve as a context for cultivating an alternative, even if amorphous, sense of collectivity adjacent to institutional settings. While visitors to Gund Hall could manipulate the system produced in the course of OS1.1, the complex interaction of input and output devices made it difficult to anticipate the effects produced by the set of spinning rings. As in Oppenheimer’s own practice, the project staged a feedback loop between human interaction and environmental affordances. Her methods, as an artist and instructor, eventually foreground a sprawling network of variably perceived inputs and outputs, where causation is neither linear nor zero-sum.