As oceans expand and storms intensify, coastal regions face a rising threat: water. Whether due to deluging downpours or surging seas, flooding has increased in frequency for shore communities. Throughout the past two decades, landscape architects and urbanists associated with the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) have explored ways in which oceanfront regions can adjust to this new, wetter reality as coastal adaptation approaches have evolved, shifting from a reliance on hard infrastructure designed to keep water out, to what architects and engineers call nature-based solutions, which often intentionally let water in. Today, GSD-affiliated designers have expanded this trajectory by prioritizing communication and education as essential first steps for adaptation efforts in the struggle with climate change.

The Looming Threat of Sea Level Rise and Storm Intensification

The inaugural report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), issued in 1990, underscored the dangers confronting coastal communities, with sea level rise positioned as a main culprit. Sea level rise stems from global warming, the IPCC explained, which results in higher ocean temperatures that cause water to thermally expand, ice sheets and glaciers to melt, and storms to intensify. A 3-foot rise in sea levels, the report warned, would severely impact coastal regions, “threaten populations in low-lying areas and island countries,” displace millions, expose even more to coastal storm flooding, destroy the built and natural environment, and force the redesign of infrastructure to withstand “flooding, erosion, storm surge, wave attack, and sea-water intrusion.”[1] (In recent years, the menace of a 3-foot bump in sea levels has grown to a worst-case scenario of a 6-foot rise by 2100—a fate that will affect thousands of coastal miles and upwards of 800 million people globally.)

Despite the IPCC’s initial warning, the need for coastal adaptation was slow to infiltrate public discussion. Then, in late August 2005, Hurricane Katina roared ashore in southeast Louisiana, bringing storm surge that contributed to the failure of New Orleans’s levee system, inundating 80 percent of the city. Nearly 1400 people died, and flooding took two and a half weeks to recede. Seven years later, Superstorm Sandy’s convergence of weather and tidal patterns overran New York City’s protective infrastructure. High waves and storm surge swamped subway tunnels, knocked out power grids, engulfed at least 50 square miles of the city, decimated area shore communities, and claimed more than 100 lives. No longer nebulous phenomena, sea level rise and storm intensification were rendered strikingly real, exacting a terrible economic, social, and human toll.

For both Katrina and Sandy, infrastructural failures disproportionately affected low-income and working-class communities—a fact that suggested issues of social inequality were built into the infrastructural system itself. This continues to hold true not only in urban settings, but in locations in all stages of development around the world. Likewise, natural ecosystems have been devastated by infrastructure such as levees, sea walls, and pumping stations, which have historically inflicted negative impacts on the environment as well as plant and animal life. With such inequities in mind, architects and engineers have started to seriously rethink dominant approaches to storm water management.

Battery Park, Manhattan, Photo by Timothy Krause. Creative Commons.

From Gray to Green

For centuries, dikes, pipes, and other human-made elements have served as industrialized societies’ go-to tactics for controlling water, either preventing its entry or facilitating its rapid removal. The Netherlands, with a third of its land below sea level, had long been a global leader in such endeavors. By the late twentieth century, Dutch experts began exploring a different approach to water management: they looked to nature, drawing lessons from processes such as permeable ground absorbing water or wetlands buffering against storm surge. Building on these ecological systems, in 2007 the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management launched the Room for the River program to strategically restore rivers’ natural flood plains. The broadened flood plains, achieved through owner-compensated land reclamation and dike relocation, allow rivers to safely accommodate larger volumes of water, which would have previously flooded developed areas. Moving forward, these renewed flood plains will help offset the rising water levels resulting from climate change.

In 2008, the year following Room for the River’s initiation, the GSD embarked on a two-and-a-half-year partnership with Dutch agencies to create the Harvard–Netherlands Project: Climate Change, Water, Land Development, and Adaptation. Characterized by the motto “Water is Our Enemy, Water is Our Friend” and spearheaded by GSD professor Jerold Kayden (MCR-JD ’79), the project involved seminars and option studios in which students and faculty worked with Dutch experts to rethink long-accepted ideas around water management. Instead of focusing on “engineering know-how to build up dikes and improve pumping technology,” they explored “open[ing] cities to the sea in such a way that natural systems can co-exist with human habitation.”[2]

Elsewhere, coastal adaptation measures that mimicked natural processes were gaining traction. Many submissions to the 2007 design competition for the Governors Island Park and Public Space Master Plan in New York Harbor addressed future rising tides and storm surge, for example incorporating recreational green spaces that could act as buffer zones during flood events.[3] A few years later, the Museum of Modern Art staged an exhibition at the PS1 Contemporary Art Center called Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront, featuring interdisciplinary design teams’ proposals to “re-envision the coastlines of New York and New Jersey around New York Harbor and to imagine new ways to occupy the harbor itself with adaptive ‘soft’ infrastructures.”[4] On the opposite coast, San Francisco launched an ambitious plan to transform Treasure Island, a former US naval base on a low-lying artificial island adjacent to the Golden Gate Bridge, into a neighborhood with thousands of homes alongside parks, plazas, open spaces, an urban farm, and a commercial town center. This sustainable development, among the first major projects of its kind, established guidance for sea level rise adaptation policy moving forward.[5]

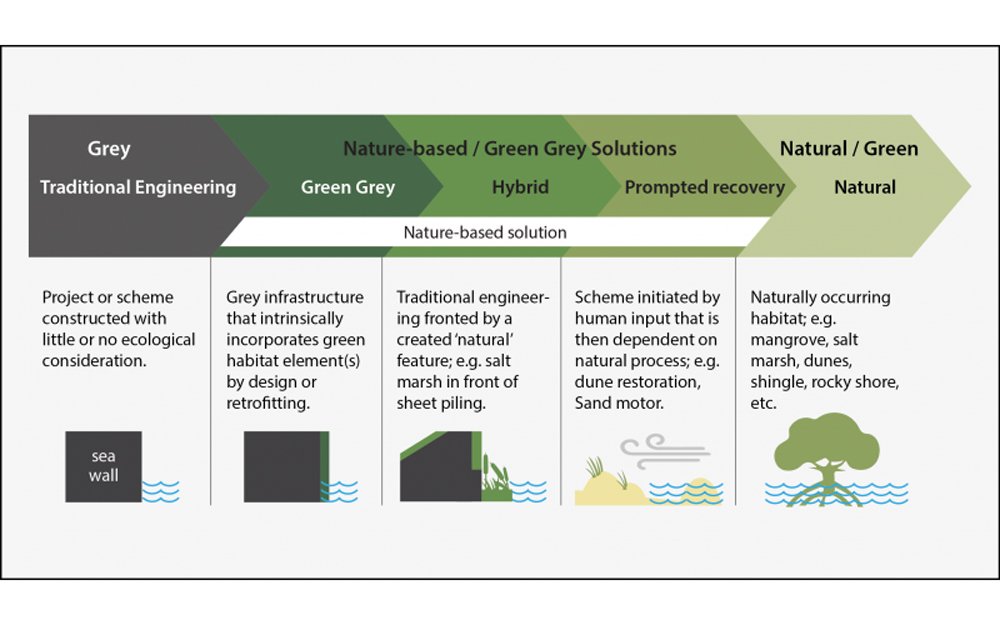

Likewise, in 2010, the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE)—the organization responsible for constructing and maintaining water management infrastructure throughout the country—announced the Engineering with Nature (EWN) initiative. Described as “the intentional alignment of natural and engineering processes to efficiently and sustainably deliver economic, environmental, and social benefits through collaboration,” the EWN framework underscored the USACE’s willingness to supplement their engineering tool kit, which classically consisted of hard/“gray” infrastructure, with soft/“green” approaches—what the US Department of Homeland Security’s Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) now calls “nature-based solutions.” The creation of the EWN indicated that, alongside designers, engineers recognized the value in reconsidering traditional approaches to flood control.

Sandy’s arrival in 2012 accelerated the search for water management solutions that combined gray and green approaches. This hybrid paradigm features in winning projects from the Rebuild by Design competition, initiated in 2013 by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Intended to foster resilience in Sandy-impacted areas through “regionally scalable” yet “locally contextual solutions,” Rebuild by Design operated as a funding mechanism for the initial phase of seven innovative projects.[6]

This includes the BIG U, designed by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and ONE Architecture & Urbanism, comprising a series of open green spaces that work with berms, deployable walls, and other hard components to serve as flood protection around lower Manhattan. Another project, Living Breakwaters, designed by SCAPE—a landscape architecture and urban design practice run by GSD alumni Kate Orff (MLA ’97 and firm founder), Gena Wirth (MLA/MUP ’09), Pippa Brashear (MLA/MUP ’07), Alexis C. Landes (MLA ’10, also a lecturer at the GSD)—with Parsons Brinckerhoff, involves artificial breakwaters that shield Staten Island’s southeastern coast from storm surge and wave action. Constructed of stone and concrete, the partially submerged breakwaters reduce beach erosion while providing habitats for oysters and other marine life. Currently both the BIG U and Living Breakwaters are advancing through multi-phased construction, demonstrating a distinct progression from water management through hard engineering (such as New Orleans’s levee and pump system pre-Katrina) to approaches that incorporate green processes.

Coastal Adaptation as a Social Movement

Since the Harvard–Netherlands Project concluded in 2010 and Sandy wreaked havoc in 2012, discussions around coastal adaptation and storm water management at the GSD have followed a similar path from gray to green, hard to soft, with programs, studios, and initiatives stretching from Canada to the Philippines, Denmark to China. Recently, the GSD has advanced the conversation by foregrounding community engagement as a necessary precursor to developing water management strategies. In other words, GSD-affiliated practitioners are considering coastal adaptation as a social movement as much as an infrastructural program. This fall, amidst offerings that address coastal adaptation and resilience around the globe, the emphasis on sharing knowledge with and learning from residents of coastal communities is clearly visible in two courses that focus closer to home: Rockaway Peninsula, New York; and Portland, Maine.

Residents of the Rockaway Peninsula, which juts from the southwest corner of New York’s Long Island, have yet to fully recover from Sandy. And with increasing land values, problematic rebuilding practices, and near full salt-water inundation predicted by 2100, life on the barrier island is not getting easier. This convergence of forces prompted Ed Wall—professor of cities and landscapes at the University of Greenwich, visiting professor in landscape architecture at the GSD, and a practitioner whose work focuses on spatial equity—to organize the project-based seminar “Rockaway’s Housing Superstorm: Between Rising Waters and Climate Gentrification.” In this course, Wall and his students collaborated with Rockaway residents to design a new public realm throughout the peninsula that connects local housing to the waterfront and provides shared space for recreation, social interaction, and transportation-hub access. With ample community input, the students then developed strategies of adaptation to respond to the rising seas in the coming months, years, and decades.

Wall believes that collaboration between experts and the communities they serve is a prerequisite for successful adaptation interventions. Yet, as Wall notes, “architects, landscape architects, engineers, and the agencies that employ them too often undertake work in a location without spending enough time there.” This results in designs that may inadvertently ignore true community needs and fail to foster the local interest that sustains a project long term. Thus, Wall’s seminar repeatedly engaged with Rockaway residents and community activists, on site and via video conferences; these interactions guided the students as they designed and refined interventions. “This back-and-forth is partly about building trust with the community,” Wall explains, “and partly about supporting the students as they learn to navigate these relationships and recognize the complexity of this type of work. It’s complicated, layered, and messy, and I genuinely believe it must start with these conversations.”

In addition to frequent engagement, Wall advocates community education through regular and honest discussion about future environmental predictions. “There needs to be some way of communicating that our landscapes are changing,” he asserts. “When we have heavy rainfalls or a drought, what does that mean? Where does our water come from, and how are seasonal tides different from daily tides?” For Wall, public awareness about climate science is an imperative, as is clarity about the temporal nature of buildings, cities, and landscapes.

Similar sentiments about communication and education feature in the work of Pamela Conrad, a landscape architect and design critic at the GSD. This fall Conrad (Loeb Fellow ’23) and Michael Blier (MLA ’94) led an option studio titled “Envision Resilience: Imagining a Future Waterfront for Portland, Maine,” part of a larger multi-university design studio and community engagement initiative called Envision Resilience Challenge, sponsored by Remain. Through Conrad and Blier’s studio, the students worked with local stakeholders to develop short-, mid-, and long-term interventions for the city’s downtown Old Port, which experienced two extreme flooding events in January 2024 alone. The studio prioritized community engagement, aligning with Conrad’s belief that “it is absolutely critical to bring the community into the conversation early, and in a safe space.” This begins by establishing a shared common ground regarding climate-related risks.

During the initial meeting with area residents and stakeholders, Conrad’s students introduced neighborhood sea level rise maps and then posed questions: what concerns you the most about these predictions? What’s important to you in this area? Where do you think we should prioritize resources? This knowledge informed the studio’s next step, which involved additional community discussion around adaptation approaches. “We act as facilitators for the conversation and listen deeply so we can hear community members’ ideas,” Conrad explains. “Then we move to the drawing board to transform their ideas into adaptation concepts, after which we return to the community with those strategies. This process leads to more long-term stewardship because community members see their ideas in the visions presented, and they’re the ones who will advocate for these projects over time.”

Among landscape architects, it is generally understood that nature-based adaptations, such as a living marsh instead of a concrete seawall, can address the risks of sea level rise and storm intensification as (if not more) effectively than hard infrastructure—and with accompanying benefits such as reduced carbon emissions and increased cost savings, human health, and biodiversity. Yet, hard infrastructure often remains the norm in coastal adaptation work, in part because there is no way to systematically assess the efficacy of nature-based adaptations. Fortunately, this will soon change. This fall, Harvard’s Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability funded an ambitious project by Conrad and Charles Waldheim, John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture and director of the GSD Office for Urbanization, to develop and distribute an evaluation methodology for nature-based shoreline adaptation solutions. This study aims to educate design and engineering practitioners, highlighting sources of embodied carbon and demonstrating that “low-carbon, nature-based infrastructure can address, rather than exacerbate, the climate crisis,” thereby laying the groundwork for the broader adoption of nature-based adaptation solutions.[7]

Conrad’s educational efforts likewise extend to international practitioners and leaders. As one of two delegates representing the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA), she recently attended the UN Climate Change Conference in Baku, Azerbaijan (COP29). Here Conrad and Thai landscape architect Kotchakorn Voraakhom spearheaded a workshop for global policymakers and launched their recently completed WORKS with Nature: Low Carbon Adaptation Techniques for a Changing World, a guide presenting 100 nature-based strategies for various contexts—developing and developed countries, urban and rural locations, coastal and inland. [8] Conceived as “a low-carbon, nature-based resource for all countries, at all scales, and for all budgets,” WORKS with Nature prioritizes communication and education as a critical next step for climate adaptation, not to mention climate mitigation and ecosystem regeneration, all efforts essential for sustained future life on our planet. As Conrad notes, “We must share our collective stories, lessons learned, and work on nature-based solutions with the global community.” In the end, “we are all in this together.”[9]

[1] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change: The IPCC 1990 and 1992 Assessments (June 1992), 106-107, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/05/ipcc_90_92_assessments_far_full_report.pdf. Note that sea levels rise and recede at different rates around the globe, depending on an area’s ground-water subsidence, distance from the equator, and other factors.

[2] See Pierre Bélanger and Nina-Marie Lister, “Landscape Disurbanism” option studio course description, https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/course/landscape-disurbanism-depolderization-decentralization-in-the-dutch-delta-region-spring-2010/.

[3] Ed Wall, interview with author, Nov. 6, 2024. All further quotes from Wall come from this interview. Wall was part of the team that established the 2007 Governors Island competition.

[4] “Rising Currents: Projects for New York’s Waterfront,” Mar. 24–Oct. 11, 2010, Exhibitions and Events, MoMA, https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1028.

[5] Pamela Conrad, interview with author, Nov. 8, 2024. All further quotes from Conrad, unless otherwise noted, come from this interview. Conrad worked on the Treasure Island development during her time with CMG Landscape Architects.

[6] “Origin and Impact,” Hurricane Sandy Design Competition, Rebuild by Design, https://rebuildbydesign.org/hurricane-sandy-design-competition/.

[7] “Salata Institute Funds Five New Climate Research Projects,” Sept. 18, 2024, Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability at Harvard University, https://salatainstitute.harvard.edu/salata-institute-funds-five-new-climate-research-projects/.

[8] Jared Green, “At COP29, Landscape Architects Will Workshop Landscape Solutions to Climate Change with World Leaders,” Dirt, Nov. 6, 2024, https://dirt.asla.org/2024/11/06/at-cop29-landscape-architects-will-workshop-landscape-solutions-to-climate-change-with-world-leaders/.

[9] Pamela Conrad, “Introduction: When it Comes to Climate and Biodiversity, How Do We Choose?” in Pamela Conrad and Kotchakorn Voraakhom, WORKS with Nature: Low Carbon Adaptation Techniques for a Changing World (United Nations Climate Change, Nov. 18, 2024), 13, https://unfccc.int/documents/644016.