Across from the main entrance to the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale stands a courtyard lined with bamboo scaffolding. An ancient Chinese structure fashioned with lashed bamboo poles, such scaffolding dates back thousands of years and remains ubiquitous throughout Hong Kong, wherever construction is underway.

This particular bamboo scaffolding, erected in a Venetian courtyard, serves a different purpose: it is both set piece and enticement, part of a collateral event called Projecting Future Heritage: A Hong Kong Archive, curated by GSD alumni Fai Au (MDes ’11) and Ying Zhou (MArch ’07) with Sunnie Sy Lau. The scaffolding draws in visitors, showcasing its artful existence while leading to an adjacent warehouse-turned-gallery that catalogs examples of Hong Kong’s post-war building typologies and infrastructures.[1] Employing natural materials and collective practices, the bamboo scaffolding evokes a sense of ingenuity and timelessness.

This year’s architecture biennale, also known as the 19th International Architecture Exhibition, carries the theme “Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective.” Explaining this title, curator Carlo Ratti aligned the Latin intelligens with multiple forms of knowledge available to humankind. (Gens, after all, is Latin for people). Nevertheless, since the biennale opened last month, reviews—including “A Tech Bro Fever Dream” and “Can Robots Make the Perfect Aperol Spritz?”— have largely focused on the omnipresence of technology. True, the high tech abounds in a range of guises, from algae-infused building materials to sensor-ladened space skins. Yet, even as the dangling automatons and LiDAR maps underscore the “Artificial,” an expansive understanding of intelligence, one that embraces the “Natural” and the “Collective,” remains palpable, especially among contributions by members of the GSD community. This undercurrent surfaces through visitors’ “low tech” experiences with sensorial input, animal encounters, and communal engagement.

A Multisensory Biennale

The 2025 Architecture Biennale encompasses 300 installations, 66 National Pavilions, and 11 collateral events (as well as more than 100 GSD-affiliated contributors). Given this concentration of projects, one would anticipate an array of sights, sounds, scents, and atmospheric conditions. What appears striking, however, is the number of projects that rely on visitors’ immersive and multisensory involvement for full effect.

While most installations discourage hands-on interaction (“non toccare!”), tactile sensation nonetheless reigns supreme. This begins with Ratti’s main exhibition, staged primarily in the Arsenale’s Cordiere (a former rope factory/warehouse), which opens with the project Terms and Conditions. Here visitors move from the bright Venetian sunlight to a dim, muggy vestibule containing the waste heat from the air conditioning system that maintains the vast hall beyond at a comfortable 23 degrees Celsius (73.4 degrees Fahrenheit). The oppressive heat envelops visitors, offering them a glimpse of Venice’s projected future climatic conditions as they move beneath suspended air conditioning units, finally emerging into the Cordiere’s cool, light-filled, low-humidity interior where hundreds of exhibits await.

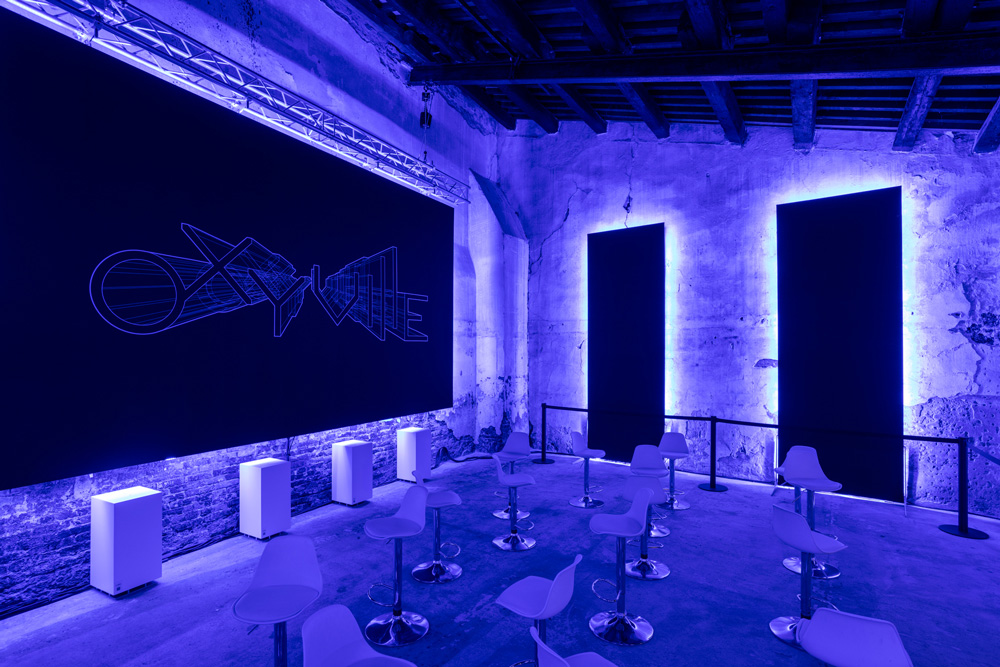

The immersive experiences continue with installations that cloak visitors in sound—dripping water; awe-inspiring music reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 Space Odyssey; humming frequencies, and more. One such exhibit—Oxyville by Jean-Michel Jarre, Maria Grazia Mattei, and GSD professor Antoine Picone—uses electronic music to explore the relationship between 3D audio and architecture. Within a space illuminated by glowing blue lights, visitors experience soundtracks that conjure different “sonic architectures,” such as that of a cathedral or, perhaps, a nightclub.

Other exhibits involve perceptible odors. Their inclusion isn’t necessarily intentional, although it is for some installations, such as Sound Greenfall and Grounded, the Türkiye Pavilion. Still, in many circumstances, discernable aromas become integral experiential components of a given project. For example, with its dense concentration of indoor microclimate-producing plants, Building Biospheres—the Belgium Pavilion, curated by GSD professor Bas Smets and Stefano Mancuso—proves incredibly fragrant. Meanwhile, the rectangular blocks of earth (chinampas) that populate Chinampa Veneta, the Mexico Pavilion, evoke the shallow-water environments in which these life-supporting landscape elements traditionally float.

The exhibits are diverse visually, with intriguing dynamic elements and textured surfaces—smoke, water, lava, wood, vegetation—to catch one’s eye. Film features prominently, at times animating wrap-around enclosures to immerse visitors in the imagery. Stresstest, the German Pavilion (which includes a project by GSD alumni Frank Barkow [MArch ’90] and Regine Leibinger [MArch ’91]), employs this strategy, filling three walls of the pavilion’s soaring main space with infrared heat maps and alarming news footage of warming city centers. (A tolling bell—our planet’s death knell?—sounds in the background). Former GSD Loeb Fellow Tosin Oshinowo (LF ’25) harnesses a similar approach on a smaller scale for Alternative Urbanism: The Self-Organized Markets of Lagos. This installation’s screens surround visitors with the bustling activity of three Nigerian markets that recirculate so-called waste items from industrialized societies (clothing, auto parts, and more)—repairing, altering, and reusing them to create a sustainable system that transcends conventional patterns of consumption.

While planning the 19th International Architecture Exhibition, Ratti and his curatorial team no doubt recognized that all this sensory input could prove overwhelming. Perhaps this is one reason behind the minimalist AI descriptions that appear, in English and Italian, alongside the designers’ longer project explanations. Some may be disturbed by these pared-down depictions, at times a mere two sentences versus the designers’ original multi-paragraph text; have critical nuances been lost? Is this a commentary on the human attention span? Does architectural discourse really require such CliffsNotes? All these may well be the case. Yet, after experiencing a few dozen installations and realizing hundreds more await, it becomes clear that, whatever else they may be, the AI descriptions are a kindness, a “low-power mode” for visitors’ mental stamina as they undertake this endurance event. An added bonus: the AI text ruthlessly eliminates the discipline’s notorious archi-speak, in theory making the biennale more accessible to the public, including the mass of tourists who roam the Venetian cobblestone streets.

Animal Encounters

Aside from thieving seagulls and Piazza San Marco’s iconic winged lion, animals aren’t often associated with Venice, by said tourists or locals. A number of biennale installations seek to change this, including The Living Orders of Venice by Studio Gang, led by GSD professor Jeanne Gang. This project uses iNaturalist, a citizen science app, to enact a Biennale Bioblitz: a crowd-sourced field study to document local animal activity during the show’s 6-month run. In addition, the firm’s exhibit in the Cordiere showcases prototypical habitats to accommodate Venice’s non-human residents—the birds, bats, and bees displaced throughout centuries of construction, which destroyed their natural architectures. Instrumental for the planet’s health, these creatures require appropriate homes in increasing crowded urban centers, and Studio Gang proposes species-specific abodes to complement Venice’s existing classical architecture.

Architecture for animals likewise plays a role in Song of the Cricket, which models a rehabilitation effort for endangered species—in this case, the Adriatic Marbled Bush-Cricket, believed extinct for fifty years before its 1990s rediscovery in the wetlands of northeastern Italy. Alongside integrated research and monitoring programs, Song of the Cricket offers modular, floating islands as portable breeding stations that reintroduce healthy cricket populations to the Venetian Lagoon. Emblazoned with “BUSH-CRICKETS ON BOARD,” these temporary habitats support multiple cricket lifecycles, reducing threats of predation and disease. Other components of the project include a sound garden featuring the crickets’ song, described “as a bioindicator of ecosystem health,” unheard in Venice for over a century.

Similarly, animals emerge as crucial contributors in the Korea Pavilion, titled Little Toad, Little Toad: Unbuilding A Pavilion. With the project Overwriting, Overriding, exhibitor/GSD alumna Dammy Lee (MArch ’13) turns to the structure’s non-human occupants—a large honey locust tree and Mucca, “the [cow-spotted] cat who roams the space as if it were its own home”—to interrogate the pavilion’s history, highlighting the “hidden entities that have silently coexisted with the pavilion.” The installation 30 Million Years Under the Pavilion, by artist Yena Young, complements this narrative with a camera mounted beneath the structure to document unexpected visitors. The footage reveals that Giardini critters regularly frequent this and presumable all pavilions, which typically remain closed to the public when a biennale is not in session. (One is reminded of Remy the Cat, the unofficial GSD mascot who trapses through Gund Hall at will.) Thus the Korea Pavilion, built in 1995 yet reminiscent of Le Corbusier’s designs of the 1920s, serves as a home for not just the architects, artists, curators, and works they produce, but also cats (Mucca and two others), mice, birds, spiders, flies, and even a hedgehog—all cataloged by hand in pencil below wall-mounted Ipads that depict their visits. Amid the hi-tech fanfare that characterizes much of the 2025 Architecture Biennale, the ease, simplicity, and whimsy of Lee’s and Young’s projects, in conception and execution, feels particularly powerful.

The Power of Community

The Polish Pavilion, Lares and Penates: On Building a Sense of Security in Architecture, offers another commanding and clever presentation that shines among the National Pavilions. Infused with its own dose of whimsy, this exhibition zeros in on the ways in which architecture creates a sense of security, relying on two concepts from two very different communities: solutions derived from conventional building and health regulations, such as roofs, electrical codes, and evacuation signs; and others rooted in traditional Slavic cultural practices like brandishing dowsing (divining) rods to determine fortuitous home placement, installing horseshoes in doorways for luck, and burning smudge sticks to banish negative energy from a space. Lares and Penates, defensive household deities of Ancient Rome, lend their name to the exhibition while its designers present these security-bestowing practices as equally valid, complementary elements that, as a brochure accompanying the pavilion states, “help people feel more secure in a swiftly changing reality.” This non-judgmental approach is exemplified by the placement of a bright red fire extinguisher at the heart of a stone-and-shell encrusted niche. Fire codes, after all, are sacred in their own way.

While highlighting the human desire for security, the Polish Pavilion also alludes to our innate tendency to find strength in community, to connect with others to share ideas, resources, and support. Since its inception in 1980, Venice’s International Architecture Exhibition has embodied this urge for the cultivation of community on a global scale. That people today continue to congregate for the biennale, even though digitalization makes it possible to distribute knowledge without transcontinental trudging, indicates that many still yearn for actual (versus virtual) contact. Two installations openly address this impulse, as they provide platforms for present-day gathering and discussion. At the same time, they offer clear connections to the biennale’s communal past.

The Speakers’ Corner, by Christopher Hawthorne, former Loeb Fellow Florencia Rodriguez (LF ’14), and GSD design critics Sharon Johnston (MArch ’95) and Mark Lee (MArch ’95), who comprise the firm Johnston Marklee, offers a forum for workshops, lectures, and panels within the Cordiere. The inspiration for this sixty-person grandstand, made of unfinished white pine, stems from the 1980 Architecture Biennale—specifically, I Mostri d’Critici, curated by architectural historians/critics Charles Jencks, Christian Norberg-Shulz, and Vincent Scully, underscoring the disciplinary role of criticism and discourse. Throughout the 2025 biennale’s run, the Speakers’ Corner is hosting a series of events focused on future possibilities for architecture criticism—including those posed by the emerging role of artificial intelligence, as signaled by the biennale’s AI project descriptions.

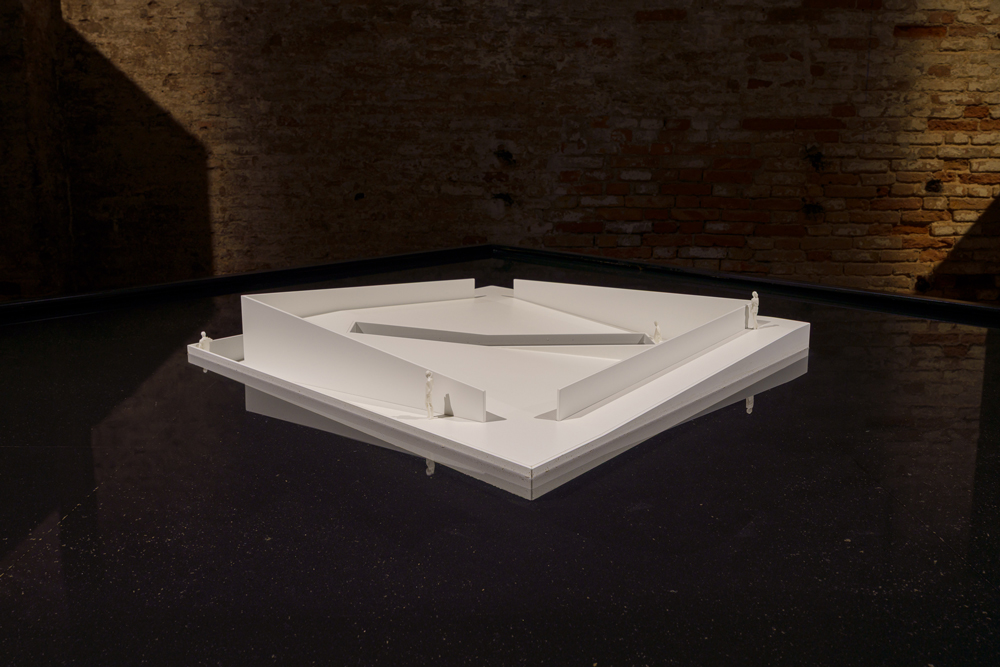

The other installation that highlights collective gathering and this biennale’s connection with the past is Aquapraça by CRA – Carlo Ratti Associati and Höweler + Yoon (founded by GSD professor Eric Höweler and alumna J. Meejin Yoon [MAUD ‘02]). Envisioned as a floating plaza to prompt discussions around climate change, this 400-square-meter entity will debut in the Venice Lagoon on September 4 before migrating across the Atlantic Ocean to join COP30 in Belém, Brazil, in November of this year. (A large model of the floating platform is currently on display in the Cordiere.) Aquapraça’s pure geometries recall those of Aldo Rossi’s Teatro del Mondo of 1979, a floating wooden theater that became an icon of the First Architecture Biennale before traveling via tugboat to Dubrovnik.

It is no accident that both the Speakers’ Corner and Aquapraça echo the aesthetic simplicity and communal intent of Rossi’s aquatic building. These projects illustrate the human desire to gather, to experience sights, sounds, and environments in real life. The sustained existence of the biennale attests to the continued significance of collective intelligence as well as creating places and events that bring people together.

[1] In addition to Fai Au (MDes ’11) and Ying Zhou (MArch ’07), Projecting Future Heritage includes many GSD affiliates. Jonathan Yeung (MArch ’20) and Wing Yuen (MArch ’22) are part of the curatorial team. Exhibitors include Max Hirsh (PhD ’12) and Dorothy Tang (MLA ’12) with Airport Urbanism: Remaking Hong Kong, 1975–2025; Su Chang (MArch ’17) and Frankie Au (MArch ’16) of Su Chang Design Research Office with Made in Kwun Tong: Between Type and Territory; and Betty Ng (MArch ’09), Chi Yan Chan (MArch ’08) and Juan Minguez (MArch ’08) of Collective with Pixelated Landscapes.