In spring 2021, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging introduced the Racial Equity and Anti-Racism Fund (REA Fund), an initiative aimed at raising awareness of how race, racism, and racial injustice affect society—especially by and through design professions—and to promote a culture of anti-racism at the GSD. The inaugural REA Fund projects, ranging from the individual to the institutional, have come to fruition in recent months, illustrating the diversity and depth of inquiry the fund has supported.

“The REA Fund has been a vehicle to bring the GSD together,” says Naisha Bradley, Chief Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging Officer at the GSD. “Over this first year we’ve had strong community input and were able to support initiatives from multiple constituencies at the school. Whether it was through one-time initiatives, community-wide programming, or semester-long classes, the REA Fund has created an innovative pathway for us to incorporate anti-racism into our community fabric and help create a GSD where many voices can be heard and all people can thrive.”

The fund has sought stakeholders from around the GSD to consider the sorts of programming and dialogue that has been missing, and to suggest solutions. It has also prioritized the need for immediate or accelerated change alongside longer term, ongoing work connecting design and anti-racist practice.

Whether it was through one-time initiatives, community-wide programming, or semester-long classes, the REA Fund has created an innovative pathway for us to incorporate anti-racism into our community fabric and help create a GSD where many voices can be heard and all people can thrive.

Naisha Bradley, Chief Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging Officer

“The REA Fund serves as one action of a holistic approach to institutional transformation,” explains Esther Weathers, Associate Director of Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging. “It requires the GSD community to pause and take stock of where we are now and imagine what could be possible. By distributing resources to faculty, researchers, staff, and students alike, we lower barriers and empower everyone to be a leader in cultivating a GSD for all.”

Technology as Racial Justice

“Access to technology, like the internet and the devices through which we interact with it, are susceptible to the racial disparities that affect our physical environments and social structures,” says Omotara Oluwafemi (MArch ’22). “In creating digital spaces, we have to begin to reinterpret accessibility and equity as terms that also apply to the virtual realm.”

Oluwafemi collaborated with Idael Cárdenas (MArch ’22) to plan the February 22 panel discussion “The Use of Technology in Design as an Avenue Towards Racial Justice,” focusing on digitally driven design narratives, technology, and mechanisms and how these dynamics intersect with questions and matters of race in design. With REA Fund support, organizers convened Michelle Chang and Marisa Parham, as well as two moderators, for conversations around how to ground considerations of equity and community empowerment amid ongoing digital innovation and growth.

Oluwafemi collaborated with Idael Cárdenas (MArch ’22) to plan the February 22 panel discussion “The Use of Technology in Design as an Avenue Towards Racial Justice,” focusing on digitally driven design narratives, technology, and mechanisms and how these dynamics intersect with questions and matters of race in design. With REA Fund support, organizers convened Michelle Chang and Marisa Parham, as well as two moderators, for conversations around how to ground considerations of equity and community empowerment amid ongoing digital innovation and growth.

“This past year has been especially challenging for BIPOC designers, as a resurgence of white supremacy and police violence negatively affected our most vulnerable communities,” says Cárdenas. “In this heightened atmosphere, Tara and I felt that it was critical to provide a platform where diverse voices can discuss these issues in parallel with how it affects the built environment.”

Through the panel, Chang and Parham observed how the digital universe can be a liberating space, but also one whose effects can vary widely based on each user’s identity. The context of the pandemic and virtual pedagogy threaded the conversation: panelists took up the intersections between technology and narrative, and how means and formats of communication and idea-sharing can shape methods of teaching and designing.

Parham has long positioned technology and digital media as fundamental to the creation of narrative and dialogue. During the panel, she shared her multimedia project “.break .dance”—a “time-based web experience,” she explained—that gathers various stories and voices, presenting them via an unfolding user-interface.

Like other projects and phenomena discussed during the panel, “.break. dance.” demonstrates how BIPOC voices and experiences, so often minimized or overlooked, can find particular resonance in the digital world. “Through technology and digital media, we are able to connect with communities across the globe to empower our local and domestic efforts for equity,” Oluwafemi says. “Digital media has given us access to histories and stories that we are not taught in school. We are able to fill in the gaps in our institutional knowledge, as seen through efforts like [anti-racist design school] Dark Matter University.”

A Moratorium on New Construction to Disrupt the Design Paradigm

Assistant Professor of Urban Design Charlotte Malterre-Barthes has shaped pedagogy and research around urgent aspects of global urbanization, addressing questions of how disadvantaged communities can gain access to political and economic resources as well as to ecological and social justice. Last spring, Malterre-Barthes engaged the REA Fund to organize the April 23 panel discussion “Stop Construction? A Global Moratorium on New Construction” with panelists Arno Brandlhuber, Cynthia Deng, Elif Erez, Noboru Kawagishi, Omar Nagati, Sarah Nichols, Beth Stryker, and Ilze Wolff.

Malterre-Barthes moderated a conversation in which designers questioned the role of construction in generating and perpetuating social and ecological injustice, as well as alternative growth models and approaches that eschew construction as a primary force. She notes that suggesting the possibility of a moratorium on new construction was bound to stir debate, especially given that designing and creating new spaces are foundational to the design fields.

Panelists questioned common definitions of architecture and design, as well as assumed models for growth and development. Deng and Erez, for example, expanded the definition of “architect” beyond the creator of a building to include maintenance and repair—a role of continual caretaking rather than a momentary or ephemeral act. Evoking his ongoing doctoral research on urban development in Tokyo, Kawagishi positioned a construction moratorium as an opportunity to consider alternative real estate models—ones that look beyond office and commercial space—as economic motors for a city or region.

Malterre-Barthes sought also to question which nations and people hold the power to direct other nations on how or what to build—or not build—given inequalities in housing, infrastructure, and other resources. A moratorium could, for instance, inhibit disadvantaged nations from achieving growth and harden socioeconomic divisions along GDP lines. Nagati and Styker challenged this idea, however, drawing from research on Cairo: there, high vacancy rates are fueled in large part by locally specific conditions that beget a need for nuance beyond GDP and economics. Wolff echoed the call for a deeper look into contextual, local complexities, pointing to ongoing debates in Cape Town over social housing. And Brandlhuber pushed for the need to reconsider ownership structures on existing buildings, to take into account the costs of embodied carbon energy, and to foster or inspire different economic systems through a moratorium.

“Controversy is inherent to the debate [over new construction], just like with growth in general—namely, how can nations with a consolidated building stock tell others they should not build further?” Malterre-Barthes says. “We also need to avoid falling into ‘academic extraction’ ourselves as we take on these debates. This means the conversation needs to be absolutely plural, something the REA Fund helped us achieve.”

“Stop Construction?” was the first in a series of roundtable discussions at the heart of the broader “A Global Moratorium on New Construction” research initiative, which Malterre-Barthes co-organized with Berlin-based architectural practice B+.

Elevating Design’s “Hidden Figures,” and Finding New Ways of Creating and Sharing Knowledge

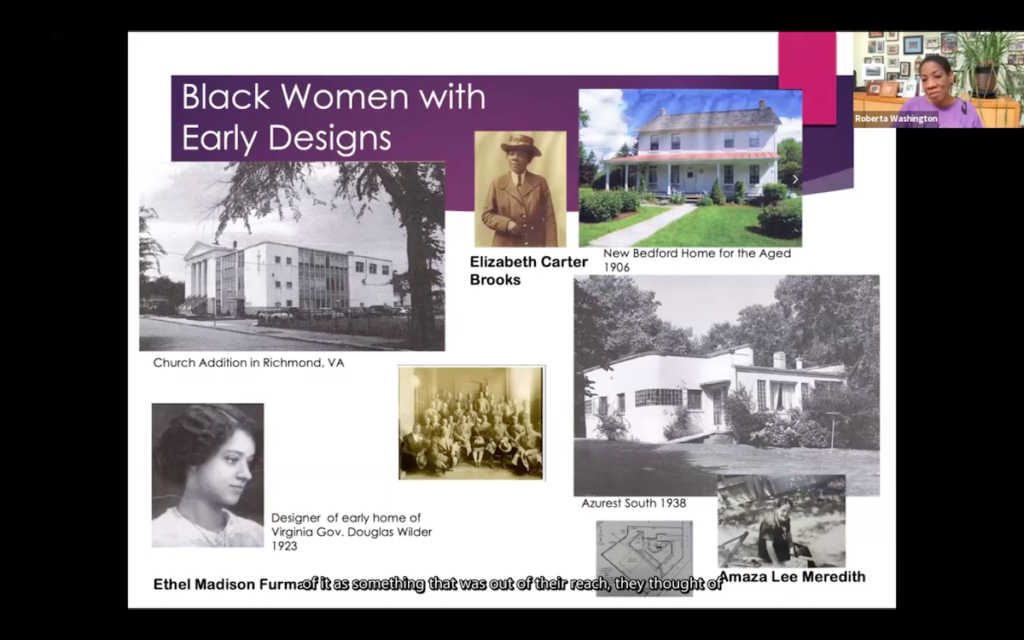

As an architect, urbanist, and activist, Hansy Better Barraza has studied the complexities of how identity and design intersect. Following years of research, as well as the cultural tumult that marked 2020, Better Barraza conceptualized the Spring 2021 Harvard GSD seminar “Hidden Figures: The City, Architecture and the Construction of Race and Gender” as a dual opportunity: an effort to reveal designers and communities who have been historically diminished or overlooked, as well as a disruptive moment in which to question how design knowledge and pedagogy—their production and dissemination—may be complicit in such inequities.

Better Barraza placed co-creation at the heart of the course’s mission—a value and an act that is fundamental to her ongoing design practice and research. She saw co-creation as an opportunity to challenge the traditional model of professor-to-student knowledge distribution, seeking instead to generate knowledge holistically. Throughout the seminar, Better Barraza encouraged students to engage their own ethnic and geographical identities as touchstones, and to seek connections between the “Hidden Figures” seminar and their concurrent studio work. Collaborative pedagogy, Better Barraza believes, can lead to a fairer and more complete understanding of design’s history.

[The REA Fund] requires the GSD community to pause and take stock of where we are now and imagine what could be possible. By distributing resources to faculty, researchers, staff, and students alike, we lower barriers and empower everyone to be a leader in cultivating a GSD for all.

Esther Weathers, Associate Director of Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging

The seminar synthesized their research into a series of public-facing resources. Student-led “Transforming the Timeline: Reclaiming Women’s Authorship in the Built Environment” celebrates a diverse set of women who offered significant but underacknowledged contributions to design and the built environment. With REA Fund support, students also produced an Instagram account and end-of-semester panel discussion that both share and deepen the seminar’s knowledge production.

“A research paper is only read by the student and their instructor and is then stacked in a folder,” Better Barraza says. “I thought instead, Let’s post our panel discussion online, let’s do a website, let’s make an Instagram page, let this knowledge be free and dispersed. It’s just so much more powerful when made public.”

One goal behind “Transforming the Timeline” is to provide an ongoing resource linked with various affinity groups at Harvard GSD that acts as a natural, co-creative element. Such a database encourages communal dialogue rather than concentrating ownership to one editor or curator—similar to the seminar’s disruption of professor as knowledge creator and student as merely a recipient.

As a title, “Transforming the Timeline” suggests not only reassessing the predominant historical narratives of design but also eschewing the concept of a timeline at all. Students rethought the linear, hierarchical dynamic of design production—exemplified by hypothetical questions such as “Who invented this building type?” or “Who did this first?”—in order to look more democratically into design history. Linear, flat narratives of design history thus open up to fresh intersections and new areas of inquiry.

Students emerged with, in many cases, fundamental shifts in how they view not only design but many other forces and powers that shape society and the built environment.

“Having an architecture background, I’ve been taught the tools and skills throughout my education to perceive design and form in a seemingly ‘objective’ matter, now understood to be through a wildly subjective and western lens comprised of Eurocentric canon and framed by white-dominated architectural and academic references and ideas of beauty,” observes Robert Nilsen (MDes ’23). “Although empathy to the users and context of our orchestrations and buildings are stressed as a component of the design process, what has been widely overlooked is how far this context extends. The seminar and the dialogue between Hansy, my colleagues, and myself acknowledged design as a node within a context of a larger societal landscape, a web intermediating between our physical environment, its influences, and the implications for its future.”

Anna Carlsson, who is cross-enrolled from Harvard Law School, credits the seminar with encouraging a reassessment of how the law functions. “In doctrinal law classes, almost everything we read is judge-written case law. That’s a very particular perspective given who’s had the opportunity to become a judge in this country,” Carlsson says. “And in the typical law classroom environment, your ability to find the right and wrong answers are based on how well you’ve managed the language of those judges. With the Hidden Figures course, we had the opportunity to sit with ideas, process them together, and apply insights to our own experiences.”

¡…. A La Calle!

Latin GSD’s spring symposium, ¡…a la calle! Art, Design, and Discourse in times of turmoil in Latin(x) America, invited artists, designers, and scholars to present and speculate about the current and future state of Latinx creative practices. Participants discussed critical practices and action models via social agency, art, and design.

“The current socio-political instability in Latin American regions and the criminalization of Latinx communities in the US invites us all to find physical and virtual spaces for reflection, action, and solidarity through the lens of art, architecture, and design,” writes Latin GSD. With REA Fund support, Latin GSD invited Latinx leaders in the design fields and other designers to join this event. Speakers included Regina José Galindo, Noemí Segarra Ramírez, Ronald Rael, and Delight Lab.

“The current socio-political instability in Latin American regions and the criminalization of Latinx communities in the US invites us all to find physical and virtual spaces for reflection, action, and solidarity through the lens of art, architecture, and design,” writes Latin GSD. With REA Fund support, Latin GSD invited Latinx leaders in the design fields and other designers to join this event. Speakers included Regina José Galindo, Noemí Segarra Ramírez, Ronald Rael, and Delight Lab.

Shifting Power in the Black Belt

While a lecturer in urban planning and design, Lily Song helped organize CoDesign, an effort to strengthen links between teaching, research, practice, and activism and to foster applied projects within the GSD and collaborative opportunities beyond. The project intrigued 2016 Loeb Fellow Euneika Rogers-Sipp, an artist, activist, and CEO and founder of Atlanta’s Destination Design School of Agricultural Estates (DDSAE).

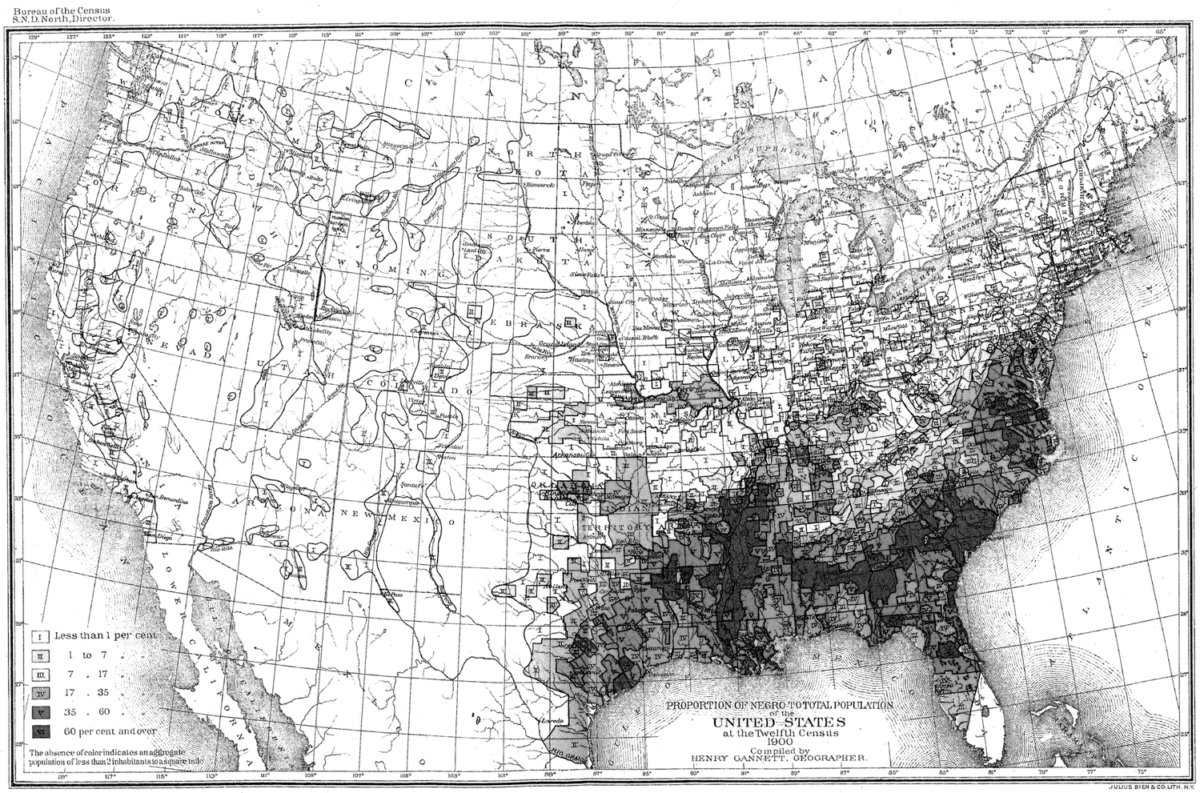

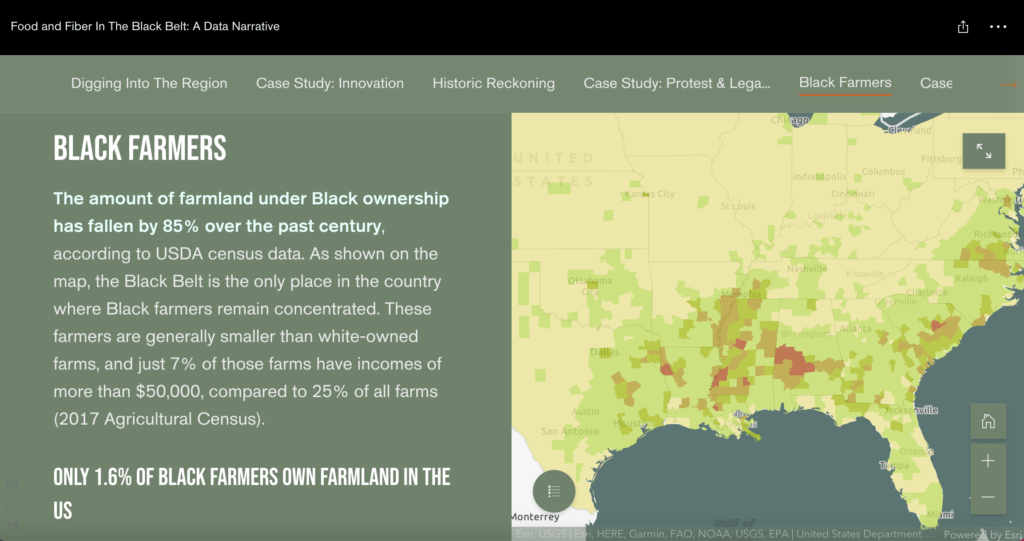

Noting a mutual commitment to promoting anti-racist practice and epistemology throughout design, Rogers-Sipp invited Song to collaborate on a research seminar focused on the so-called Black Belt region—a band of the American South stretching from Virginia to Texas in which plantations and slavery were endemic. A full-service art and community-design school that takes the Black Belt region of Georgia as its campus and canvas, DDSAE has 10 partner-site locations. The school aims to “celebrate and reimagine the profound culture and history of food, farming and hospitality through the creation of a Black Belt Reparations Design Residency and education center that can serve as a replicable model with a national ripple effect.”

Song says, “Having studied with Black radical thinkers and activists like Robert Allen and Phil Thompson, who look to the Black Belt as the cradle of American freedom movements and cultural traditions, I received this as a real honor.”

Song and Rogers-Sipp’s Spring 2021 field lab arose amid ongoing dialogue over the proposed Green New Deal, a congressional resolution to combat climate change and generate jobs in clean-energy industries. The CoDesign Field Lab research seminar worked to gather, analyze, and illustrate data in order to make a case for the Black Belt region as prime siting for Green New Deal initiatives. Organized into five teams, GSD students mapped out opportunities and assets in the Black Belt region, especially as related to production of food and fiber, energy and waste systems, climate resilience, mobility, and access to other resources. The teams also examined regional stakeholders, decision makers, and resource holders in order to gauge the power dynamics at stake in planning out a Green New Deal. With a focus on reparative planning and design, the goal of the seminar was to seek to compensate for and heal past injustices while establishing fair, constructive approaches for forward progress.

The seminar concluded with “Black Belt future histories,” in which each of the five teams collaborated with DDSAE students and community leaders to create multimedia narratives that imagine and, in some cases, propose design solutions for the Black Belt. Cynthia Deng (MArch/MUP ’21) designed a website gathering these narratives, including storymaps and other analysis, as well as information about the various GSD and DDSAE participants. The REA Fund enabled the field lab to collaborate with mentors and DDSAE partners, and enriched the lab with support from teaching associates.

Reflecting on the power of connecting GSD designers with DDSAE’s students, Song says, “This was, of course, owing to the DDSAE’s ongoing youth and intergenerational leadership efforts, along with the lead the DDSAE partners took in prompting mutual guidelines for cross-nourishing and engagement, which were critical infrastructures for the ensuing co-design.”

(1, 2) Work by CoDesign Field Lab and Destination Design School of Agricultural Estates is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://codesignfieldlab.cargo.site/