When I began studying architecture in the 1980s, students would often get asked at crits what, exactly, those blank white or beige walls indicated on their drawings or models were intended to be made of. The answer, almost inevitably, was “concrete.” Concrete was the wonder material, the realizer of dreams. The reliable, universal one-word answer. The staff would, inevitably, roll their eyes. But that reliance on a blank material rendered as an abstract surface has been threaded through the history of the last century of so of architecture. In the beginning, even architects themselves could only dream of abstract planes of concrete. Le Corbusier, Rietveld, and the others built walls of brick, rendering them so they would appear as concrete—smooth, featureless, as if drawn rather than built. They made concrete through manifestation.

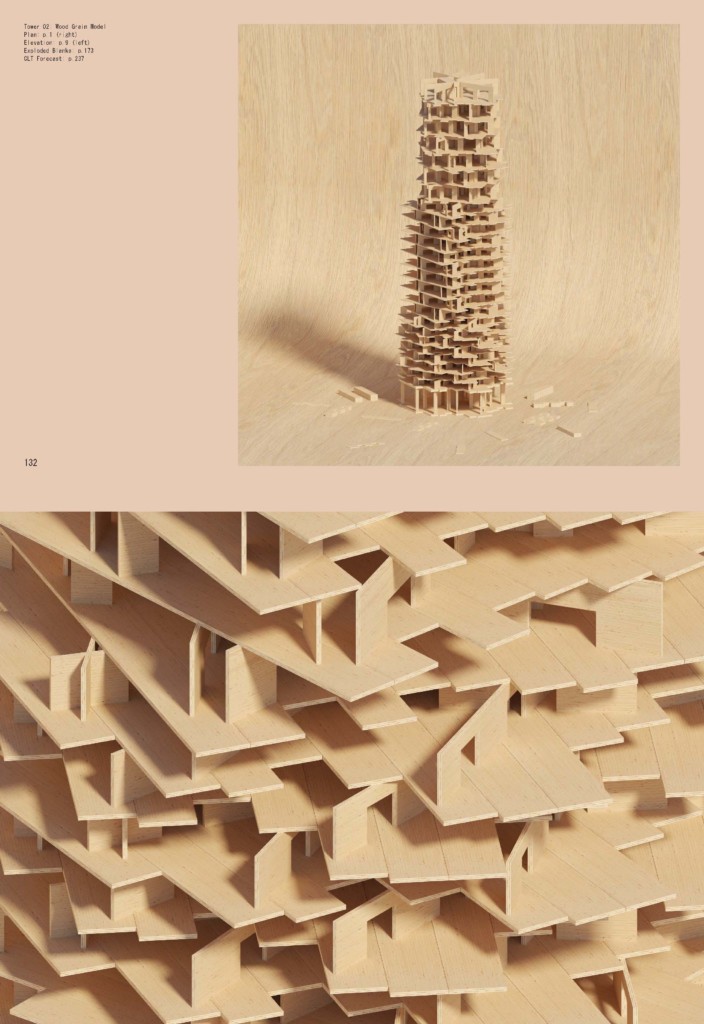

A century on, with the world more aware of impending climate crisis, that one-word answer of “concrete” might be dumber and even less acceptable than it was then. The response now, however, might well be “CLT.” Even more than concrete, big panels of cross-laminated timber, cut in a spotless factory by robots, far away from the mud, sweat, and swearing of the construction site, looks like the future. Prefabricated, clean, as much drawing as material, rendering as reality, it represents the new wonder material of our eco-aware, guilt-burdened age; the world-saving, carbon-soaking, multifunctional stuff sent to salve our consciences in the creating of new buildings we know to be wrong, in attempting to make architecture at all.

It is a heavy burden for one material to bear. And that is why Hanif Kara and Jennifer Bonner, who teach together at the GSD, have compiled a book that attempts to feel a way toward a new language for CLT, a material that looks like it has everything, but that hasn’t yet coagulated a sense of theory, meaning, or material culture around itself yet.

The book’s title, Blank (Applied Research and Design Publishing/ORO Editions, 2022), hints at this emergent identity, the still-unformed nature of a material that is both lumber and number, wood and data, a slab that exists between the forests and the digital. In one way, CLT is nothing new. It’s a close cousin of the plywood which emerged as a mass-market material a century or so ago and became a staple building product after having been adopted from other industries including aviation.

Clearing my parents’ old house out the other day, I took an ancient Singer sewing machine to the dump. Heavy as hell in cast-iron, it came in its own vaulted carrying case. I’d guess it was from the 1920s and that curved wooden top was probably the product that propelled plywood into a mass-market material. Singer’s slice of the market was so huge in the early 20th century that their adoption of bent plywood for their sewing machine cases gave this new wonder-material the scale to become an accessible material, one that subsequently came to define varying strands of modernism, from Aalto’s and Breuer’s ergonomic loungers via the streamlined bars and railway carriage interiors of Deco to the spartan studio-interiors of Case Study houses and artists’ studios.

Plywood however was mostly a surface rather than a structure. It’s true there were all kinds of laminated beams and ply products but we still probably think of it as a surface, a sheet. CLT is surface, too. But also structure. It is wall but also floor, ceiling, roof, insulation, internal finish, and the rest. Its versatility is almost comical. It holds, perhaps, a similar status in our age as not only concrete did to the modernists but as plastic did in the postwar era. It looks like the future; a total, wraparound environment.

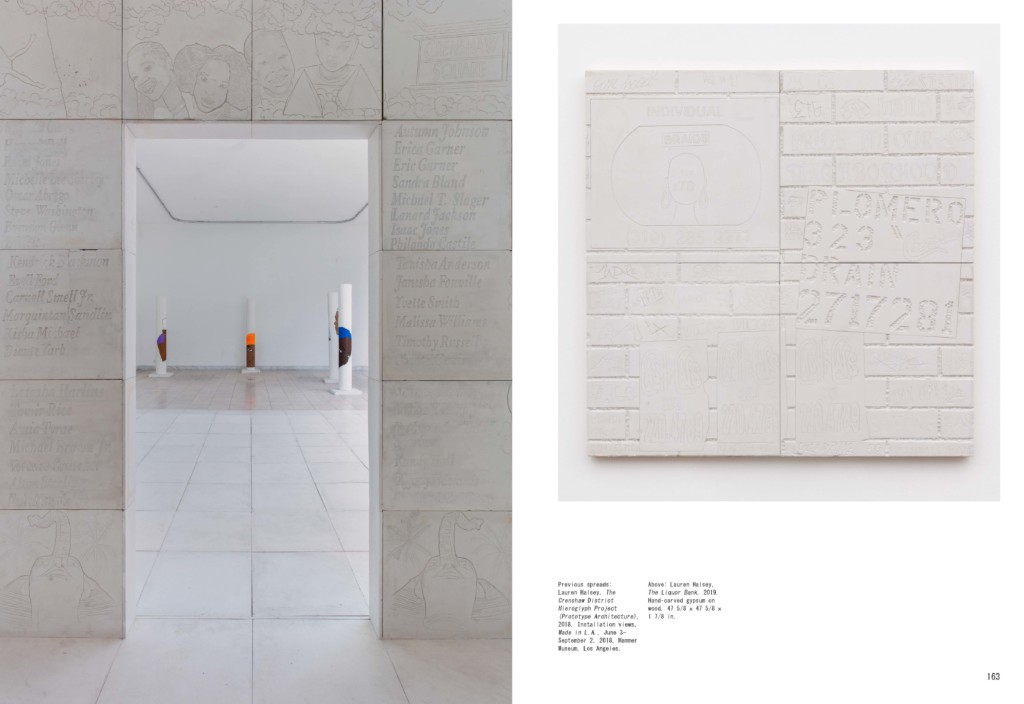

Right: Lauren Halsey, The Liquor Bank, 2019. Hand-carved gypsum on wood, 47 5/8 x 47 5/8 x 1 7/8 in, Page 163, Blank.

On the other hand, it also smells like the past. It might be high tech in its manufacture but CLT is still lumber. Its future should seem assured then, particularly in the US, where the history of housing has been one of adopting the cheapest, easiest timber construction techniques. The American house is already an all-timber affair: the balloon frame, timber windows and doors, shingles, log cabins, lodges, sticks of timber nailed together. It should be simple to segue into CLT construction in which all of that comes in one package.

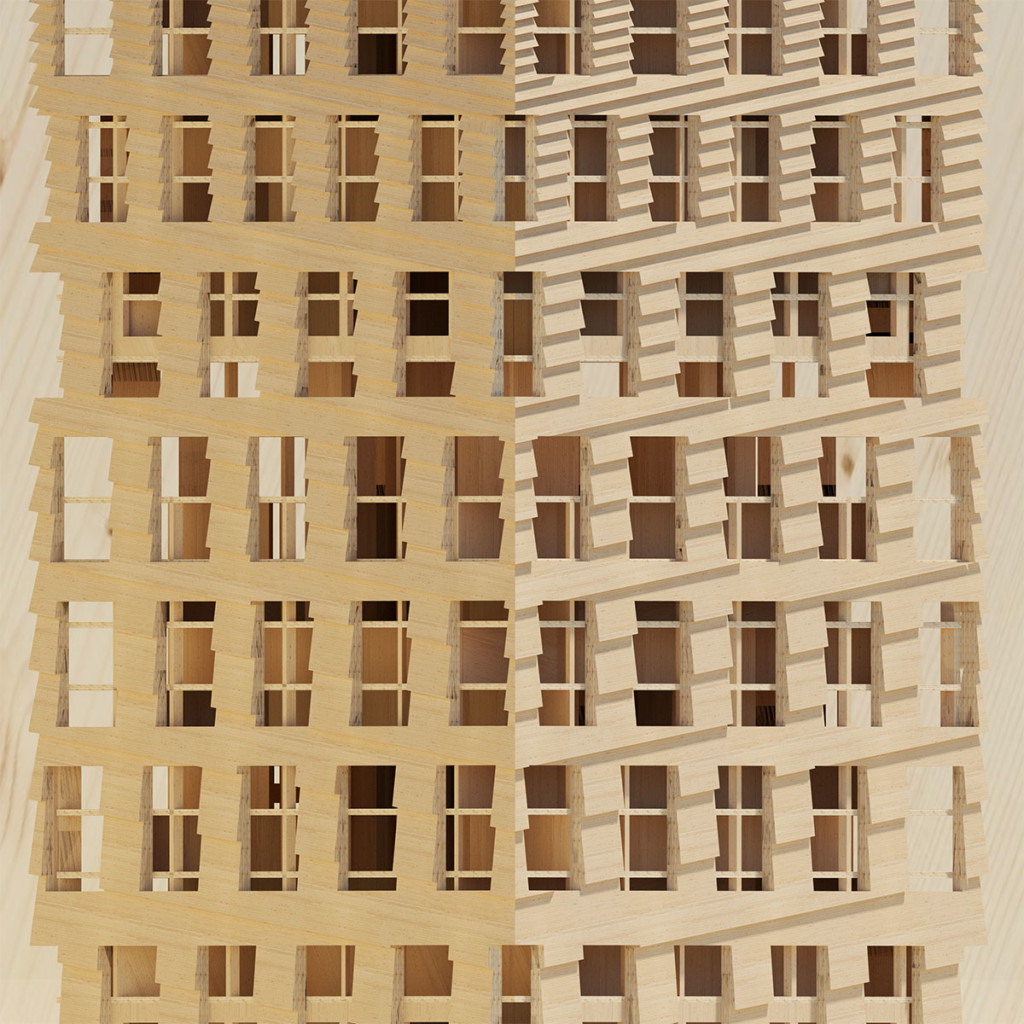

The writers here outline possible histories and futures, their texts interspersed with designs— plans, models, cutout kits of parts, propositions for a new language of architecture constructed around the capabilities of a material that does so many things at once. Along with the optimism, there is a sense of feeling a way toward new modes of expression. If the designs can look a little familiar, shot through with elements of deconstruction, wiggly walls, Swiss seriousness, and parametric ambition, many of the texts consider what the shift means. This kind of mass timber, Hanif Kara points out, is now being employed in ways more akin to how concrete is currently used in construction. It’s an odd shift—the move from the formwork leaving its imprint on the structure to the timber being employed directly—the return of the uninverted grain.

Erin Putalik puts mass timber back in its plywood context with a brisk potted history and Courtney Coffman chooses to look at the qualities of the book’s title, the curious blankness of the material. In his essay, Sam Jacob points out the cartoonish qualities of CLT, the ways in which cutouts and punched openings might resemble the cat-shaped holes in a wall through which Tom has fled at speed or the fake/real ACME tunnels constructed by Wile E. Coyote. There is something clunky in these cutouts, a super-graphic approach to the material as two-dimensional with extruded depth, rather than the complex strata of a more familiar wall or door frame with its codified layers. It has a weird confluence with foam board as a substrate for models, a super-simplified language blown up to 1:1 without translation in material quality.

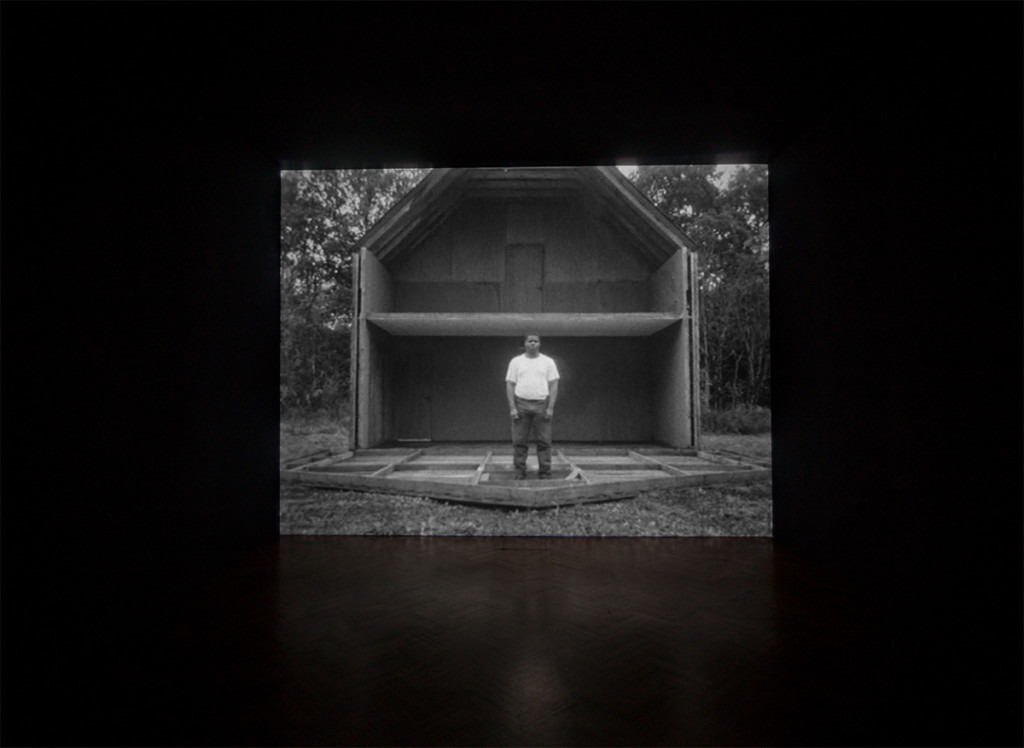

It is also, as Elif Erez (March ’21/ MDes ’22) points out in her essay for Blank titled “Deadpan CLT”, impossible not to think of the scene from Buster Keaton’s Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928, featured above) in which the facade of a house rips away from its walls and falls on the deadpan comic in the most perfect way so that his form is accommodated by an upstairs window. The scene was resurrected in Deadpan (1997) by British artist Steve McQueen, who subtly subverted it as an echo of the invisibility of the Black body in 20th-century popular culture. That delaminated elevation is a cipher for CLT, a thing both seriously substantial and comically weightless, sign and signified. There is something slapstick about an entire elevation built from a single sheet as it appears here (though of course this was frame and shingles). It reduces architecture to the condition of a stage set, a flat, something fake built only to represent reality and enable the suspension of disbelief.

Other contributors, including Jennifer Bonner, point to the condition of the blank as something already fully assimilated in fine art (she singles out Mavis Pusey; perhaps she might have also alighted on Richard Woods or even Roy Lichtenstein) who used the “plank-ness” of timber as a shorthand for materiality. Elsewhere Gehry, Rossi, Mies, and Corb appear, sometimes as plywood pioneers, at other times as adopters of the blank slab which could be concrete or marble—but why not CLT next? Even Lewerentz makes a guest appearance (in Nader Tehrani’s essay) as an architect who adopted one material—brick in his case—as if it were a contiguous surface, in often surprising and surreal ways, anticipating the way in which CLT is employed as a total environment, a laminated bubble.

Other writers here comment on the unsettling similarity of CLT structure to a supersized architectural model. Like the basswood or balsa wood architects meticulously incise to building miniature models in which everything is simplified, complex structural beams and details are stripped out and one material, one strip of wood is left to represent all surfaces and both internal and external finishes, CLT, with its clunky depth and chunky cutouts can look like a hypertrophied miniature. It has that quality of a photo taken with an endoscope in a tiny model or those mesmerizing snaps you sometimes see on social media of the inside of a musical instrument, a violin or a guitar suddenly appearing as a kind of Gehry phantasmagoria with a shaft of light piercing the F-holes and the struts and bracing: the everyday made suddenly unfamiliar.

Many of the authors point out something both curiously cuddly and unsettlingly uncanny about the material. In its grain, its feel, its smell, it is wood; but in its use it is concrete and in its manufacture it is digital. It is that hybridity that has made it simultaneously so attractive and so difficult to pin down, to position in the architectural palette.

Mass timber is, in its way, the architect’s dream material. It is (relatively) sustainable, a renewable resource, prefabricated, digital in its milled manufacture, precise, warm, and able to elude the requirements for the endless layers of finish and insulation which have made a mockery of Victorian and early modernist calls for “honesty” in construction and the show-and-tell approach to elevations. But perhaps sometimes, when we get what we dream of, we don’t know quite what to do with it. Regulation is still catching up, the notoriously conservative construction industry is still not quite convinced, and planners remain, despite endless screeds about sustainability, stuck in concrete.

Every new material, of course, provokes its own reaction. CLT’s super-sustainable halo is now being questioned by some for its liberal use of glue. Dowel-laminated timber (DLT) is occasionally touted as the next next big thing, avoiding petrochemical adhesives entirely. But it looks like CLT is, for the moment at least, here to stay. Blank is as much a comment on its newness, the lack of imprint on the culture, as it is on the character of those enigmatic slabs.

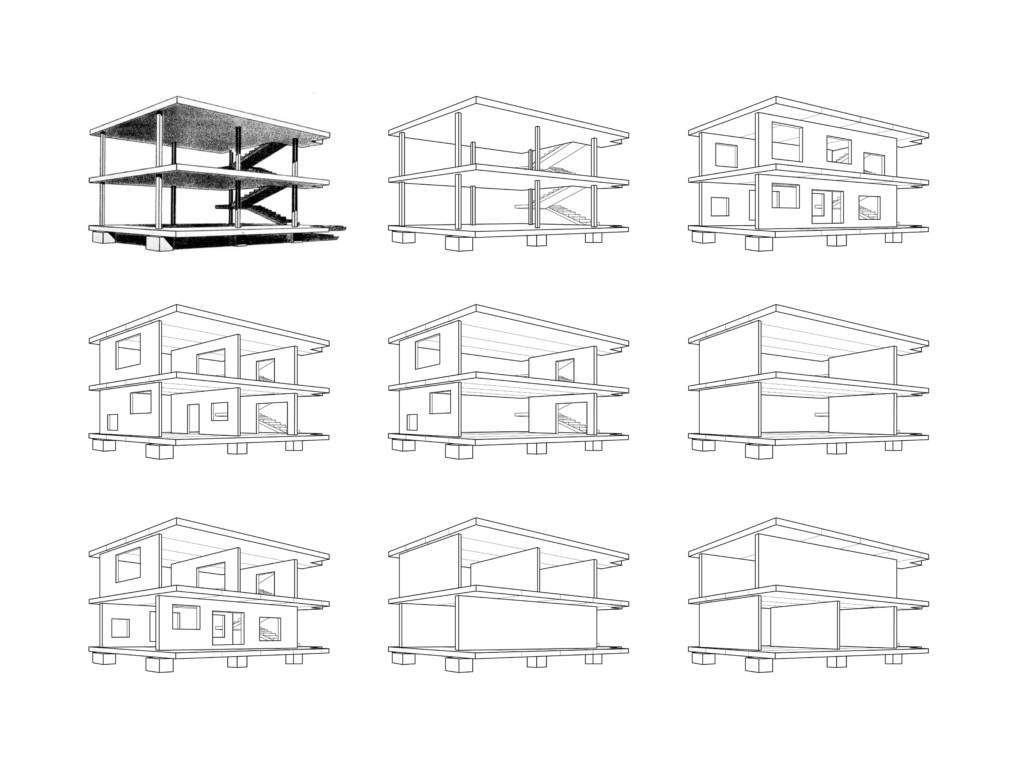

Concrete, Kara points out, had Le Corbusier’s 1914 Maison Dom-Ino—the ubiquitous image of the column and slab—that remains the model for almost all contemporary construction. The boosters of CLT have not yet emerged with an ur-model as elemental and memorable as this, perhaps because the results might just be too simple, too bizarrely familiar—a house-shaped house, a box. Ironically, Kara suggests, CLT would make a better Dom-Ino house than concrete ever could as planes provide more rigidity than reinforced concrete columns. There is no single image for CLT like Corb’s for concrete in this book, rather an increasingly complex series of explorations of form, each of which points in different directions as attempting to suggest that the possibilities are infinite.

The construction of the American balloon frame house, which still seems so simple, fragile, and astonishing to Europeans, was a result of a number of factors. First the availability of cheap timber, second the abandonment of the guilds and master carpenter networks of Europe which prescribed long apprenticeships and complex jointing techniques (along with the propensity of people to build their own houses using limited skills), and third the mass production of the nail as a machine-made and abundant good. The construction industry since then has become specialized and exclusive, though the framing technique remains.

Perhaps CLT needs its barn-raising moment. Perhaps its real adoption will need not only the complex renders and undulating lines of attempts at a parametric city of CLT towers but a return to the cartoonish world of Tom and Jerry and Buster Keaton. Perhaps Spike’s doghouse is a better model than the most complex CLT skyscraper. The charm of the material lies precisely in its elemental simplicity. Anyone who has ever built a model, used Lego, or played with a dollhouse can understand how it works. The problem is not problematizing it, but making it legible. Should be easy.

Right?