Moments of intense constraint have driven architecture toward seismic ruptures, which go on to determine how people build and live for centuries. We are within one such moment today. As a pandemic forces communities across the world to reconsider how and where people assemble, questions arise around how to augment the built environment accordingly, and which of these augmentations become new paradigms.

Events like this punctuate history. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 ruptured American architecture in ways that would directly shape the 20th-century city. After fire had charred many of the city’s wood-constructed buildings (and sidewalks), building code was updated to favor flame-resistant materials like brick, stone, and steel, which then became rudiments of urban skylines. Within a decade, the earliest steel skyscrapers started rising; a new type was born.

A century and a half later, wood has started looking good again. As designers have toyed with how wood might recapture the American architectural imagination, one format has arisen as a steward: mass timber (“mass” as in “massive”)—a generic term that includes wood-based material of various sizes and functions, including familiar glue-laminated (glulam) beams and laminated veneer lumber (LVL).

But it’s cross-laminated timber, or CLT—boards of wood glued together in perpendicular stacks to create a thick block—that has truly ruptured the canon. “Builders see [CLT] as a way to construct midrise structures faster and cheaper,” wrote the Washington Post last year. “City planners see a fast track that could help reduce housing shortages. Architects love its light weight and look. And some environmentalists tout its ability to lock up carbon to combat climate change.”

Jennifer Bonner and Hanif Kara speculate on the possibilities of a so-called “Scandinavian Effect,” fueled by mass timber and the new lenses it offers on material and structural advancement, constructability, and form.

CLT arose as a popular building material in Europe throughout the early 2000s, especially in Scandinavia. Canadians started building with it before long. This past November, Archinect revealed Mitsui Fudosan and Takenaka Corporation’s plans for a 17-story, 70-meter-tall wood-frame office building in Tokyo, which would become the tallest wooden building in Japan.

CLT’s American invasion has been hampered by the nation’s highly prescriptive building code—one legacy of the Great Chicago Fire—and by the near-ubiquity of stick-frame construction. But as wood, and CLT in particular, has attracted more interest in recent years from designers, developers, and builders alike, United States industry regulations are starting to follow suit. “Developments in code are happening right now with mass timber within the US,” observes Jennifer Bonner, associate professor of architecture at the GSD. Bonner would know—she recently cast CLT as the star of her first built project, Haus Gables, a two-story house in Atlanta, Georgia.

With Haus Gables, Bonner questioned the very rudiments of how architects design, and inspired a closer look at CLT’s potential to generate new types or effects. She tackled the CLT challenge alongside project engineer Hanif Kara, professor in practice of architectural technology at the GSD, and a longtime mentor.

While engineering Haus Gables, Bonner and Kara hatched “Mass Timber and the Scandinavian Effect,” a spring 2020 studio that framed CLT within questions of cultural instigation and identity alongside the material’s physical properties. Bonner and Kara speculated on the possibilities of a so-called “Scandinavian Effect,” fueled by mass timber and the new lenses it offers on material and structural advancement, constructability, and form. They point to parallel currents: the Bilbao Effect—that city’s reinvigoration via a new cultural nexus, the Guggenheim Bilbao—and the Dubai Effect—architectural illustrations of free-market capitalism via gravity-defying skyscrapers.

To test these speculations, Bonner and Kara wanted to apply the Scandinavian Effect to a tabula rasa of sorts—the American South—and see what might stick. “Suddenly the students couldn’t make a purely Scandinavian architecture, but it became something other quite quickly,” Bonner says. Weeks of dialogue and iteration led the studio to speculate on CLT’s potential in new and varied settings. Prompted to design both a house and a mid-rise tower in Raleigh, North Carolina, students experimented with and forecasted where and how CLT may expand its roots.

Tectonic Shifts

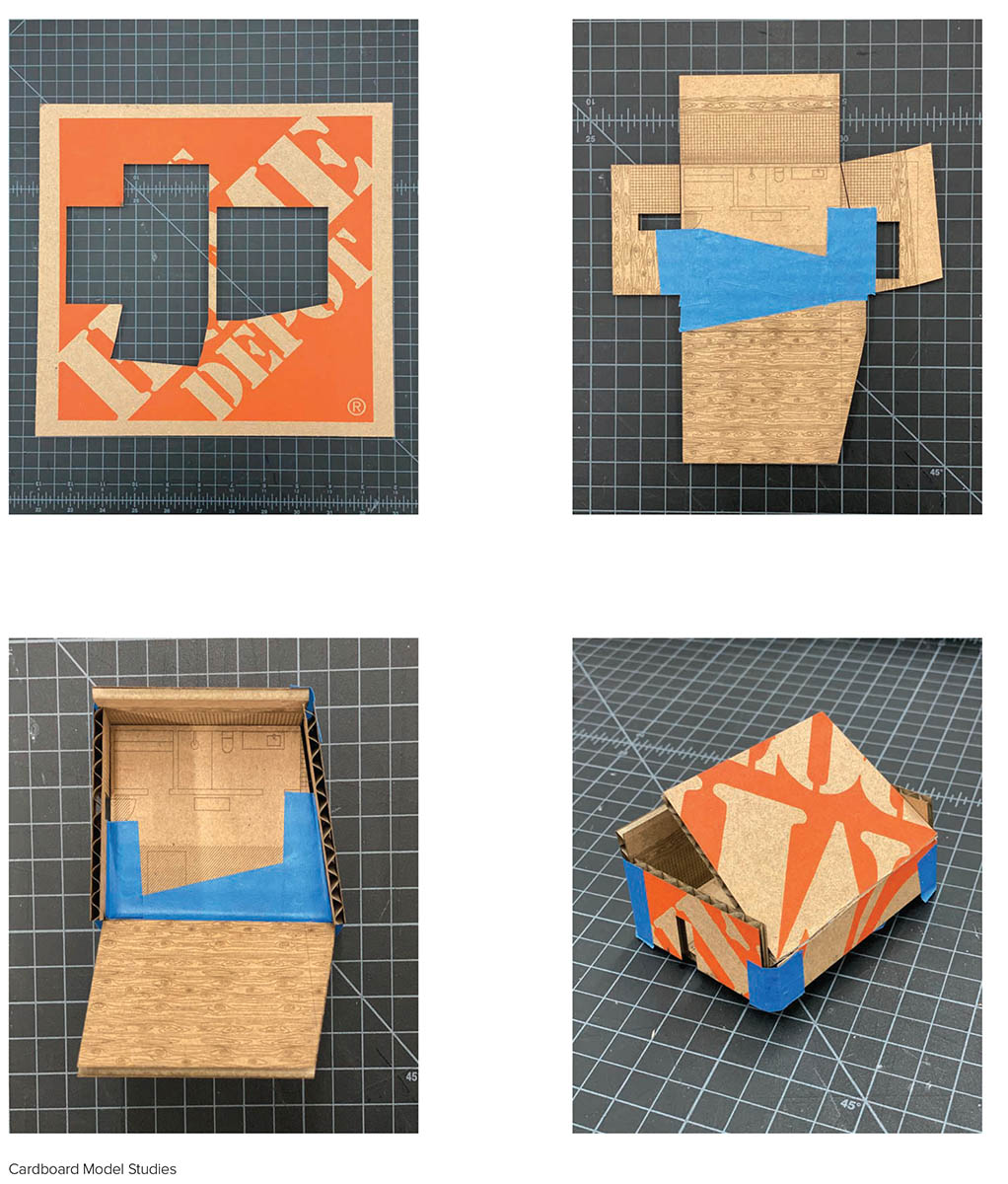

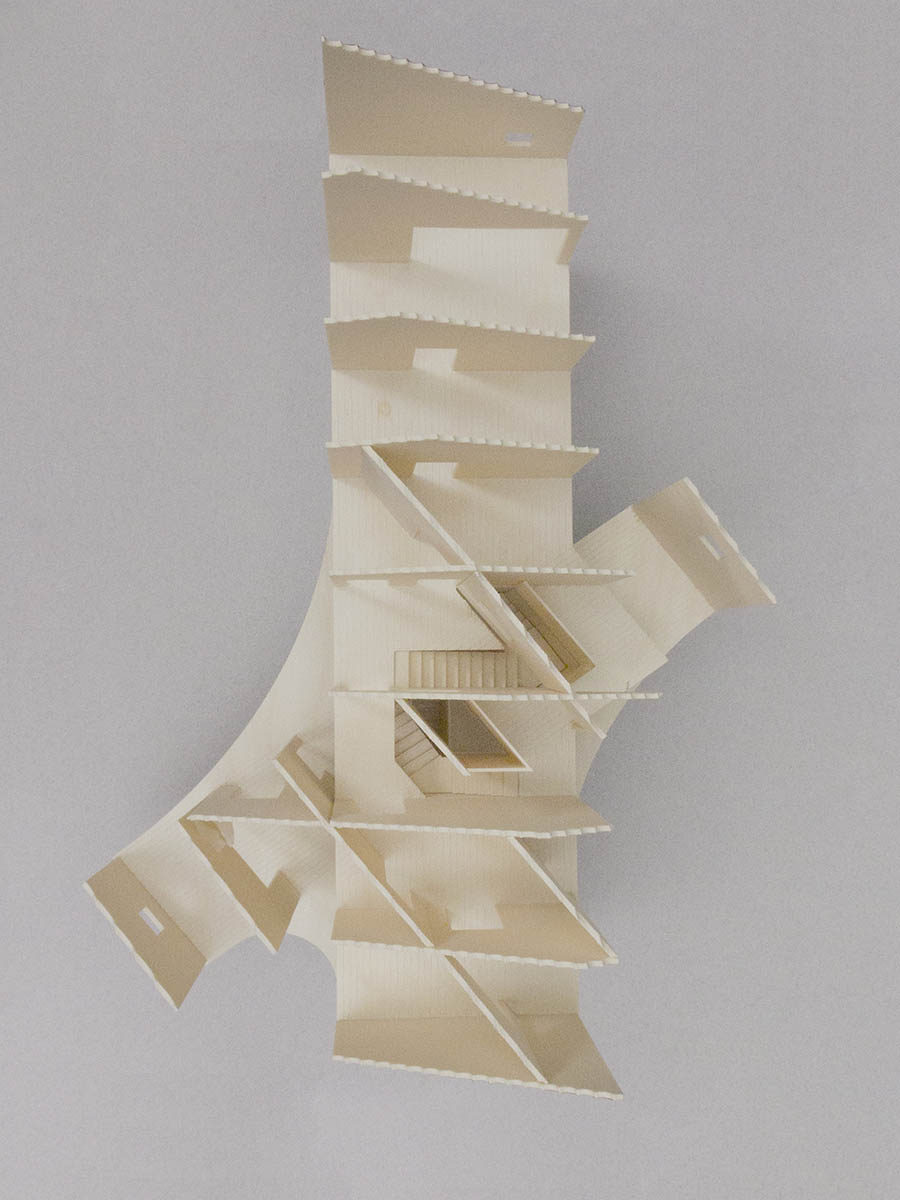

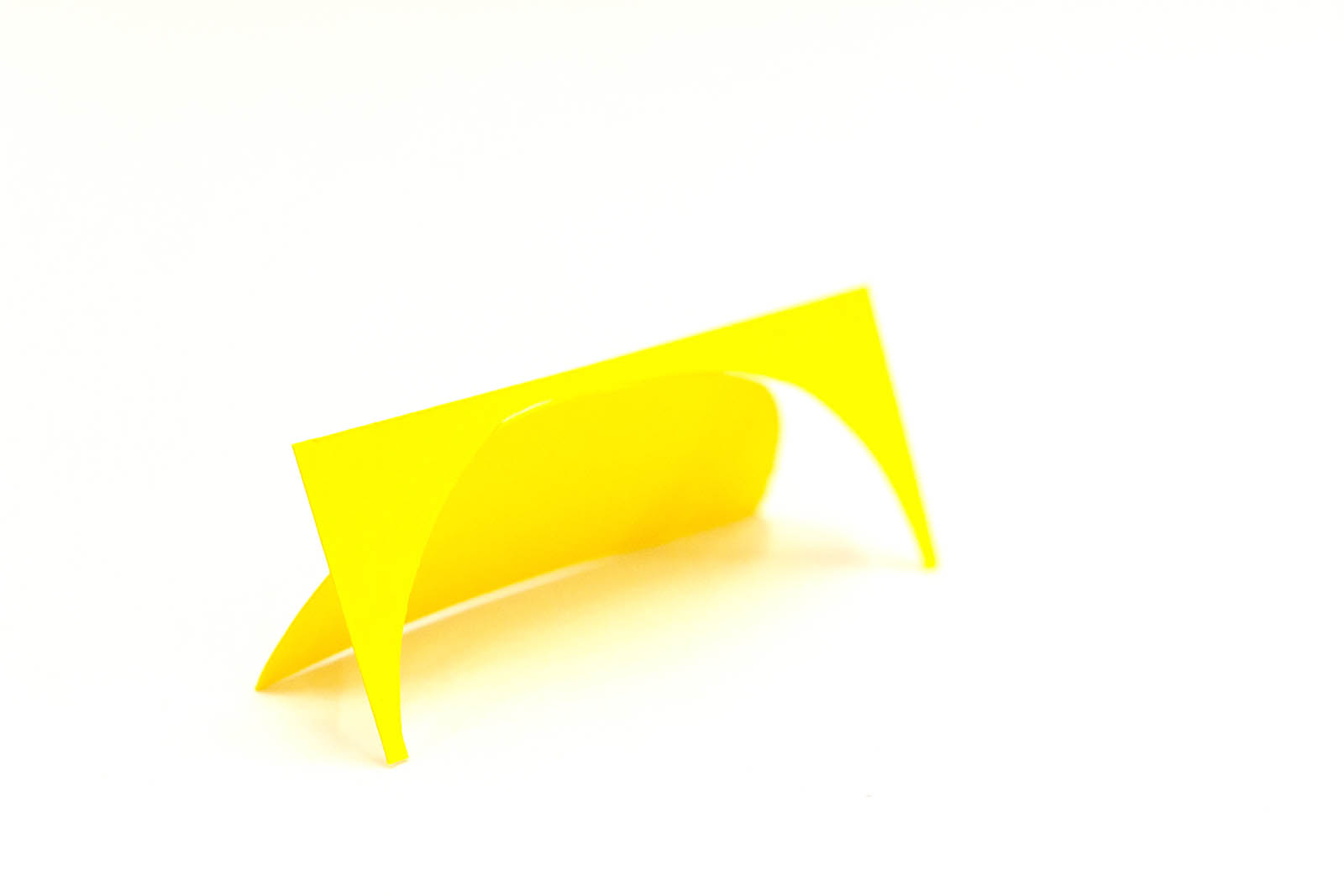

Bonner had planned to be on-site for construction of Haus Gables. Instead, a travel snafu grounded her in Cambridge, and left her monitoring a security-camera feed as 11 trailers delivered 87 CLT panels. “The whole thing looked like an architectural model being assembled in place,” Bonner recalls. “If you squint your eyes, watching the panels being installed at that scale, one could imagine: This is the way we cut up materials—chipboard, foam core, and whatever else is on our desks—and make models.” In fact, the house was snapped together much like its miniature cousin, The Dollhaus, the intentionally scaled 1:12 model, which Bonner had created as a research iteration through her design practice, MALL.

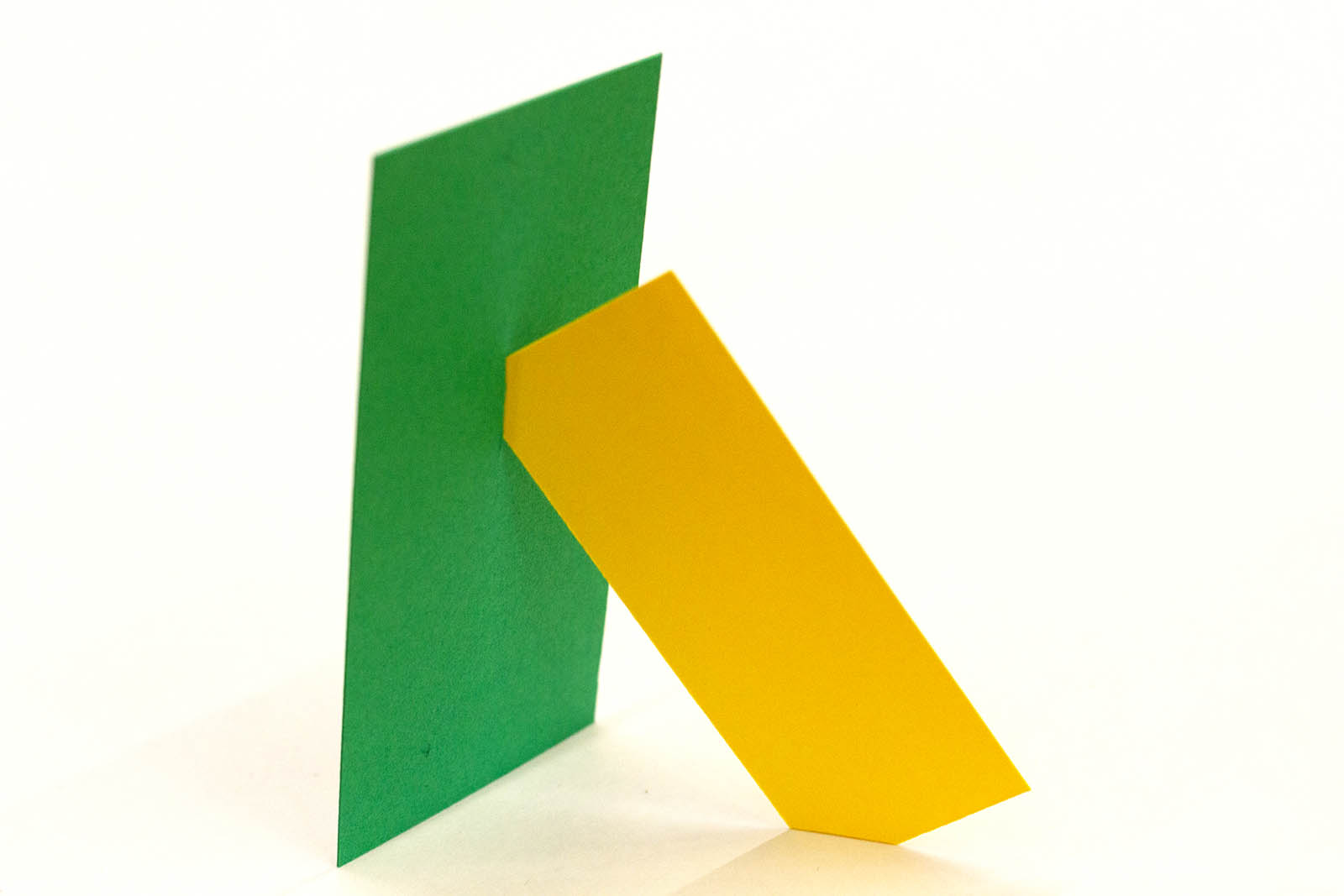

For the studio, CLT’s diverse characteristics established it as a prime representational canvas for testing architectural possibilities: It can evoke both paper-thin origami and big-block Brutalism; it can be folded and manipulated, but can also withstand extreme weight and pressure; it lends itself to experimentation and play, but begets intense precision and calculation.

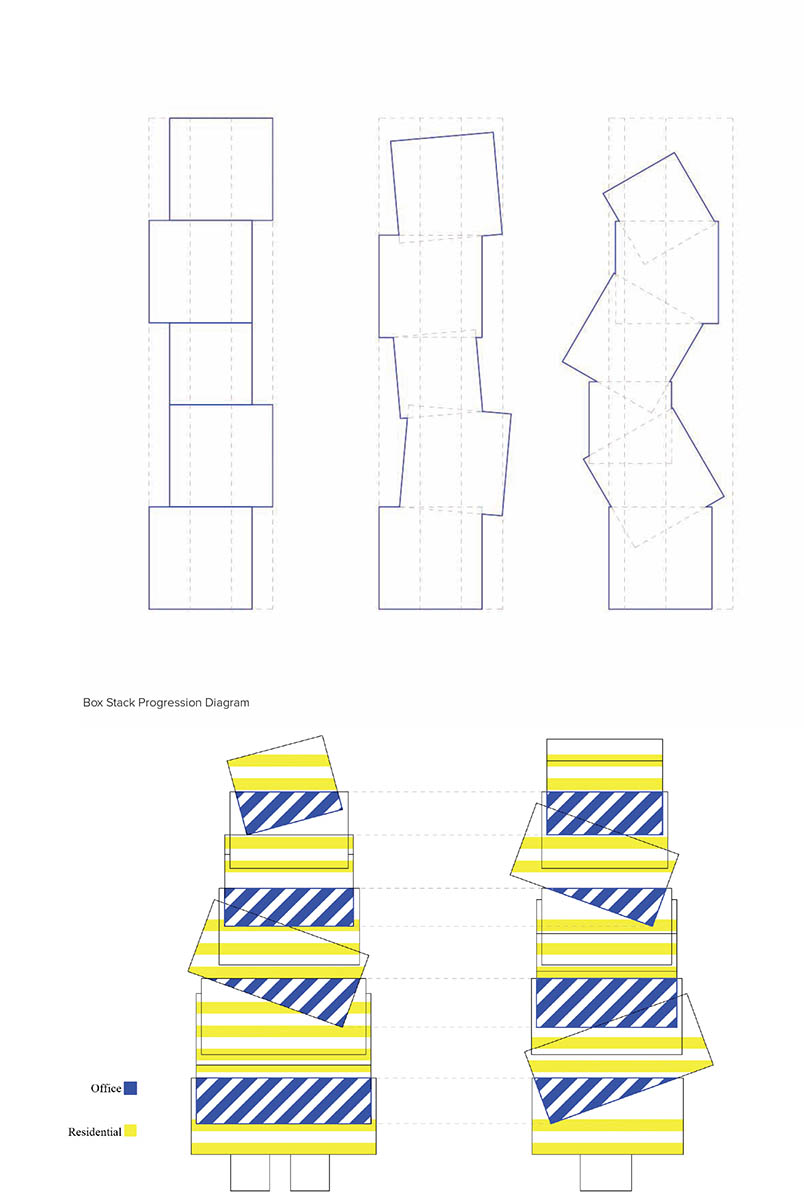

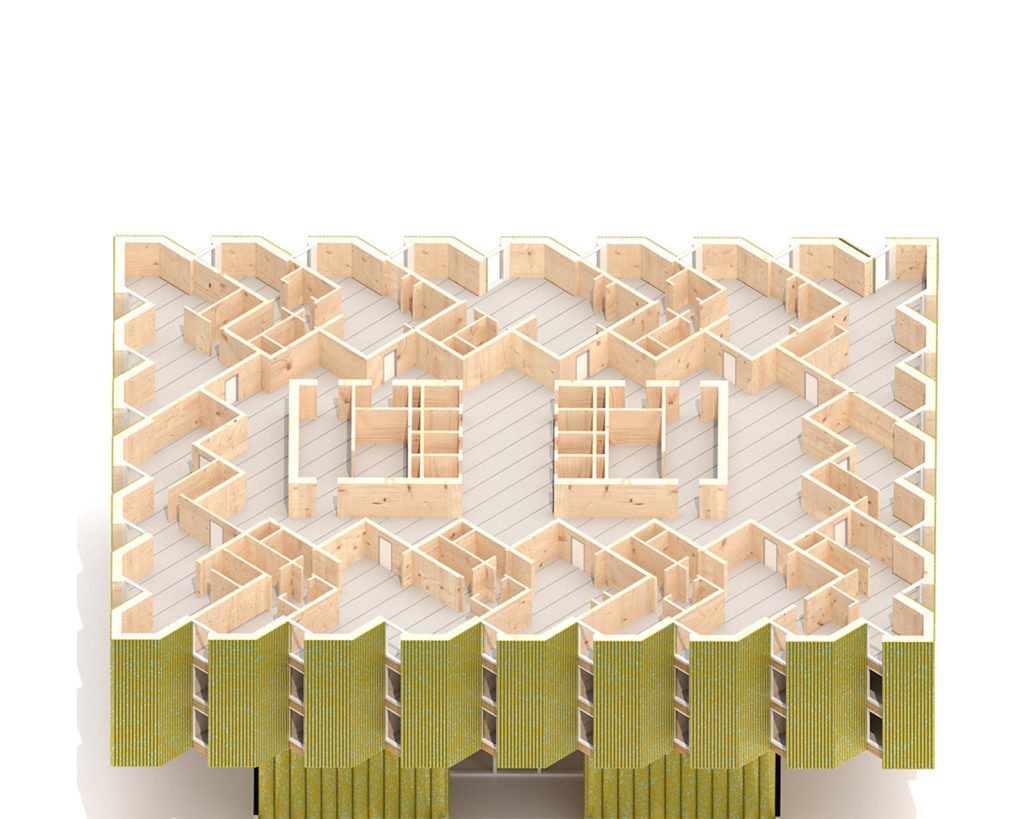

The students spent the first few weeks getting to know their new material a bit better. Aryan Khalighy (MArch ’21) began his experimentation with a crude test: he watched empty cardboard boxes fall and stack themselves under simulated gravity, producing a pile of nested mass that appeared like an irregular tower. Similarly, Edgar Rodriguez (MArch ’20) conceptualized CLT as piled-up mass, from which he realized the opportunity to experiment with the underbelly of the roof. Calvin Boyd (MArch ’21) started the design process for his “Notch House” with a single roof gable, which he then multiplied, creating both added interior space and a central CLT core. Boyd cut treads and slots into that core, generating a stair column that bears the rest of the house’s CLT structure. He describes the effect as one of levitation, illustrating CLT’s ambiguity between heavy and light. (Bonner, too, “started from the roof” with Haus Gables.)

Others identified different tectonic opportunities around which to organize the house. Benson Chien (MArch ’21) looked to the inner-wall spaces that result from traditional “balloon framing”—the use of standard two-by-fours to generate a house’s cubic skeleton. Chien wondered if, instead, layered CLT panels could generate a different wall structure, if not a new typology.

Each of these designers used so-called CLT blanks—structural sheets composed of three-ply, five-ply, and seven-ply CLT panels—as their main ingredient, exploiting the opportunity to play with stacking and layering. Chien’s shotgun-style “McMansion” stacks layers of CLT to form walls, then carves openings in the CLT blanks that serve as both windows and room thresholds. Aesthetically, Chien translated “suburban kitsch” from surrounding homes to the CLT blanks and cutouts of his McMansion, acknowledging the marching spatial rhythm of the shotgun-house typology while metabolizing the house’s surroundings.

“On the scale of the panel, one can remove portions of the CLT blank to easily create unique apertures or carve out layers to form custom interior patterns,” observes Ian Grohsgal (MArch ’21). “On the larger scale of multiple panels, one can take advantage of the ready-made quality of CLT to arrange them in unique patterns and to create larger readings.”

Anna Kaertner (MArch ’21) applied CLT blanks to so-called accessory dwelling units—self-contained apartments within an owner-occupied home, either attached to the main dwelling or in a separate structure—interrogating the tendency for the larger house’s structural hierarchy to predominate. Kaertner’s “Big/Little House” centers a staircase that creates a shared skylight for the two houses. She reimagined the roof as beams instead of planes, with interconnecting logs generating a scalloped roof. The resulting curved wall binds the two houses in elevation, generating two sides—one smooth, one serrated—and revealing a new CLT grain through aggregation.

“CLT is an extremely malleable material, and its expression does not need to be planar,” Kaertner says. “Irregular geometry and curves do not produce labor- or materially-intensive processes because the geometries are produced at the same moment and use the same process that produces CLT itself. This makes it possible to seek out these new expressions for connection and structure.”

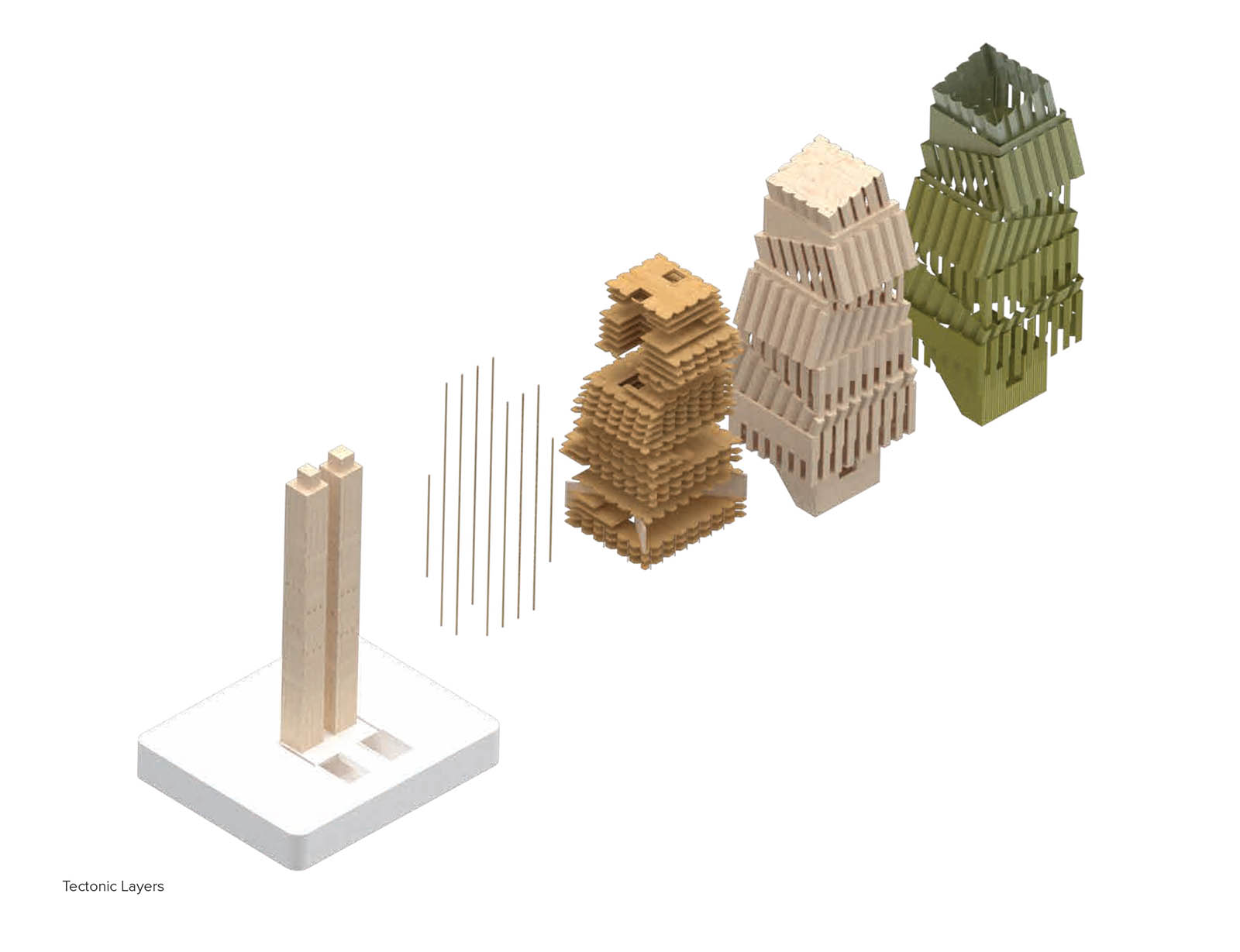

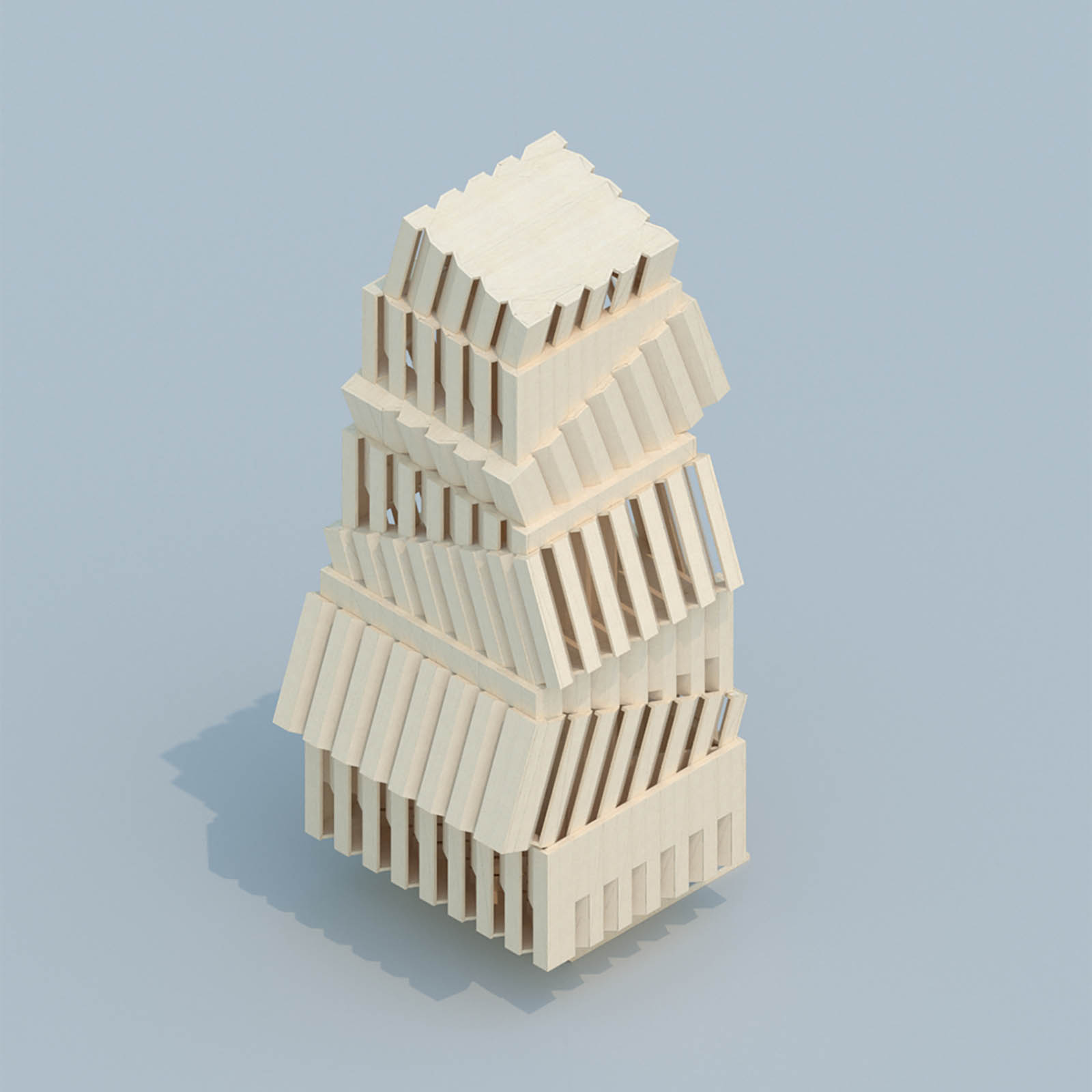

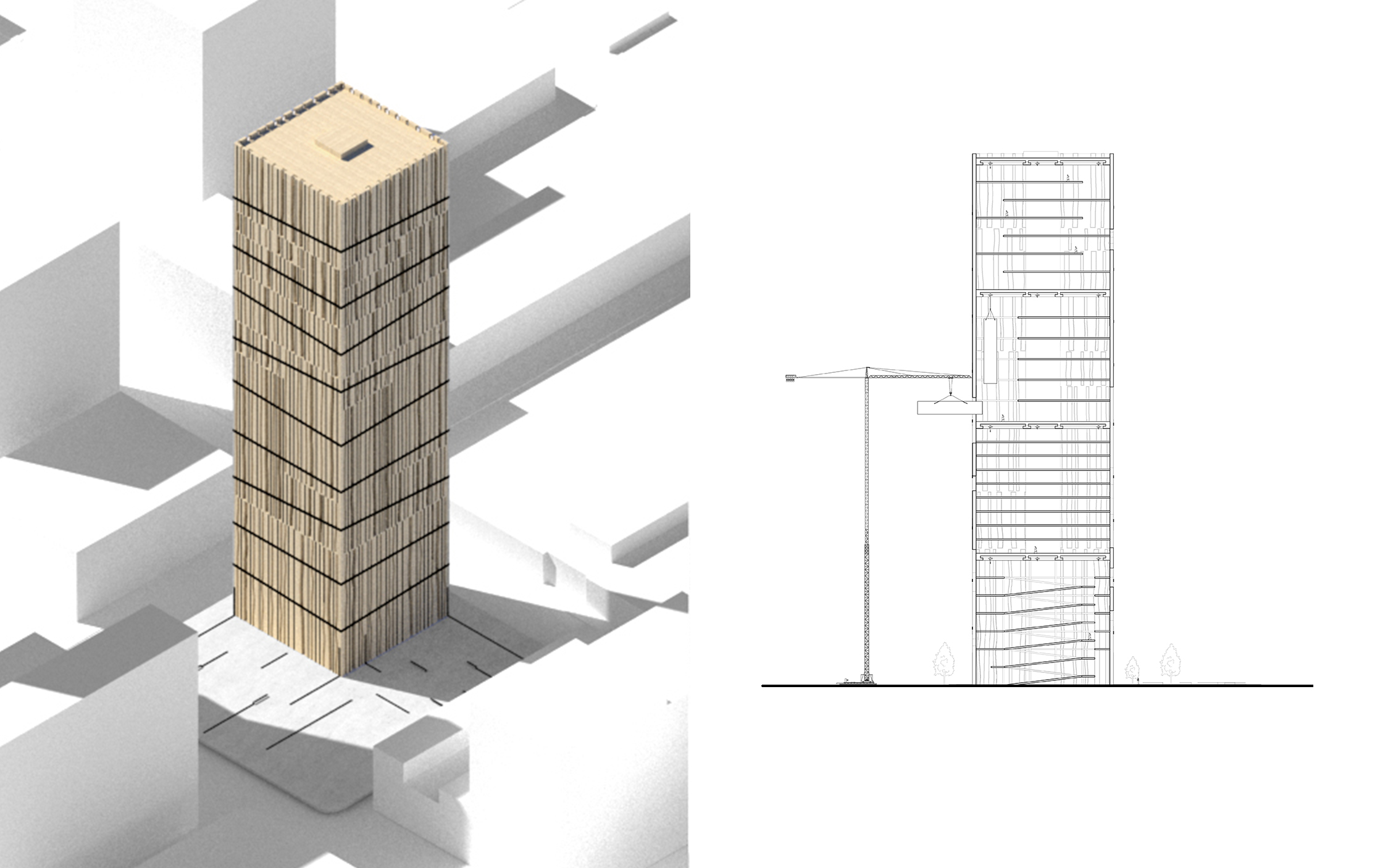

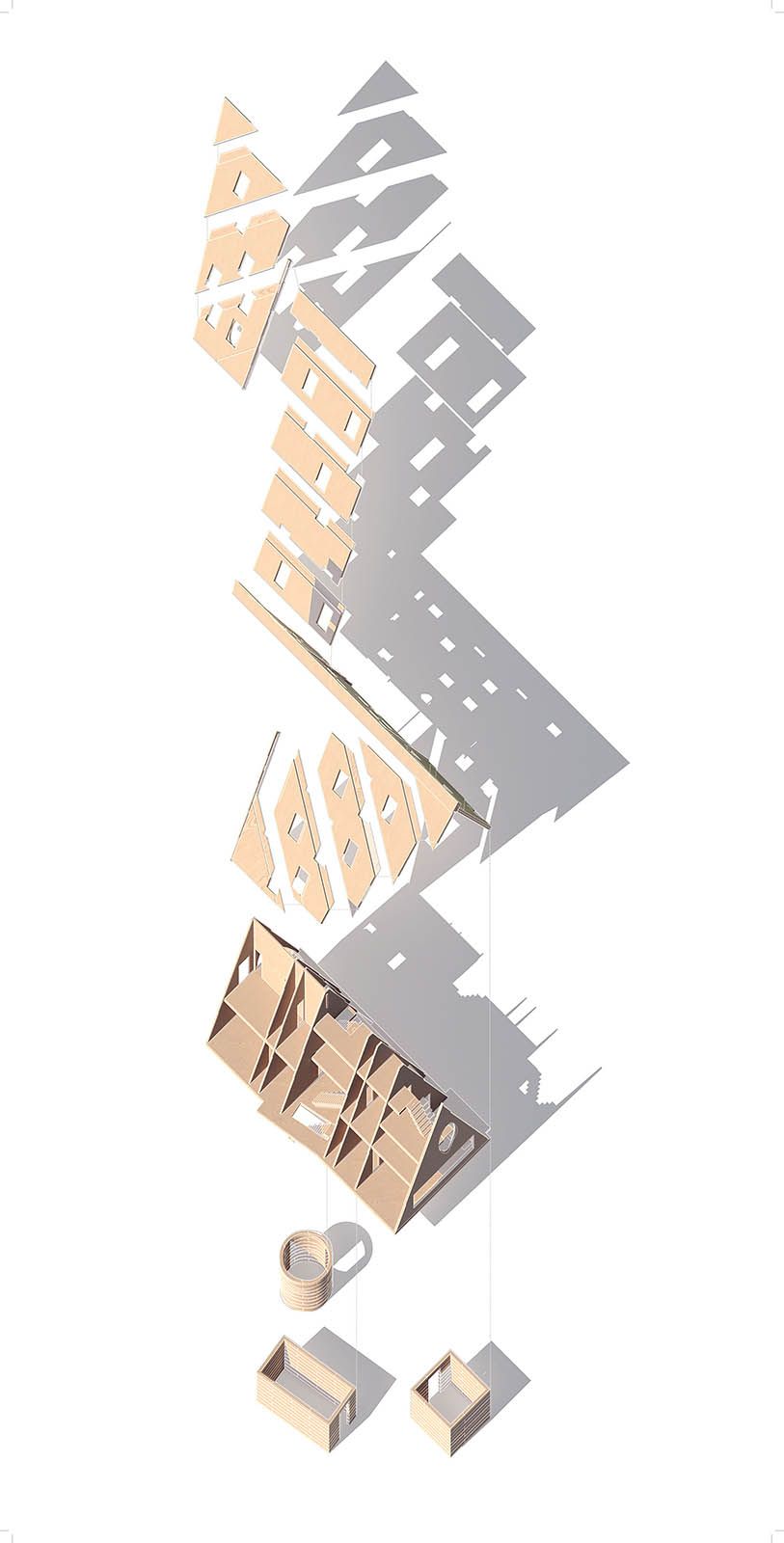

House design offered an organic testing ground for CLT—after all, wooden houses dot America—but wooden towers remain an anomaly. Despite this, CLT’s ability to bear weight qualifies it as an apt ingredient for the American tower. Anna Goga (MArch ’20) designed a mid-rise that embraces CLT’s sheer bigness and suggests how the material’s format could generate an entirely new tower typology.

Goga began with simple cuts into CLT blanks, using small pieces of steel at each cut to conjoin pairs of panels. After 400 slices and 400 bandages binding 300 panels, Goga generated an exoskeleton in which the facade line sits inside the tower. This CLT tube comprises four 24-meter-tall zones with a gantry system of cranes built into each of the four ceilings, allowing for reassembly of floor plates and walls with endless variations. (Here, Kara raises a precedent: Google’s European headquarters in London’s King’s Cross, which offers the largest CLT floor in Europe, a floor that is entirely removable or changeable over the building’s lifespan.)

“We come to an interesting point where a CLT blank encourages us to customize the building three-dimensionally,” Goga says. “I was exploring the idea of the after-life of a building and the possibility to reassemble it from the inside, which is potentially possible with light and easily assemblable CLT panels.”

As CLT’s tectonics offer the enticement of “scaling up” such reassembly and reconfiguration, designers see grander opportunities for rearrangement or reconsideration of design typologies. Reviewing Khalighy’s CLT tower unit plan, GSD professor Oana Stănescu noted a “kind of mini-suburbia” emerging—a suggestion of such interplay between CLT tectonics and larger-scale typologies.

Customizably Unexpected

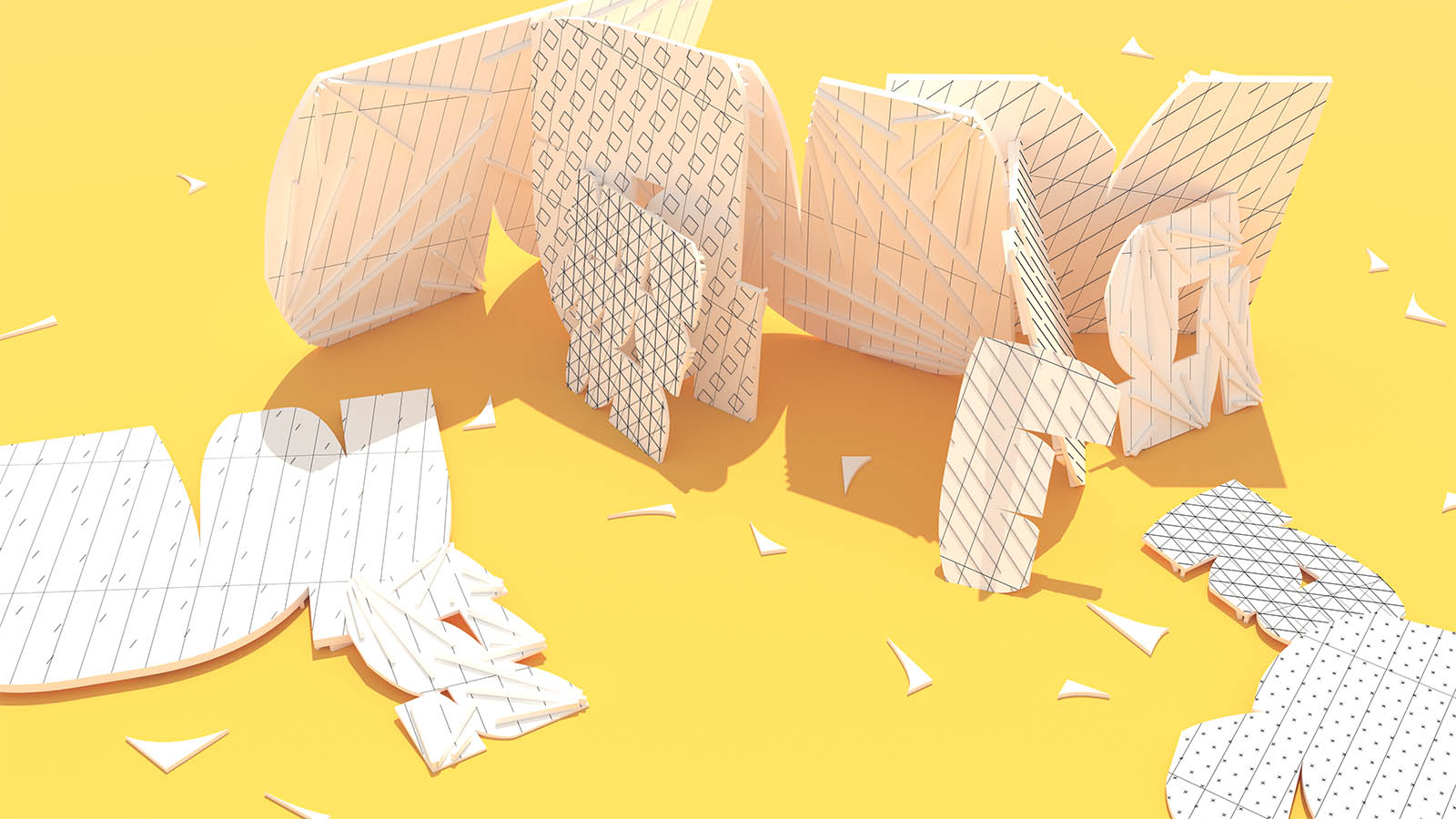

While Khalighy stacked cardboard boxes, Hiroshi Kaneko was carving paper snowflakes. “With early study models, I took advantage of our inclination as architects to use thin, easily workable paper,” says Kaneko (MArch/MDes-HPDM ’21). After leaning paper sheets against each other, he trimmed corners in ways that allowed the paper to retain planarity while introducing subtle, two-dimensional curves, gesturing toward the CNC technology used to machine-cut CLT panels.

“This studio gave us the opportunity to bring to CLT what steel and concrete already benefit from: boundlessness,” Kaneko observes. “The work of this studio, the work of bringing new metaphors into building materials, helps lift the bounds we impose upon materials and opens us up not necessarily to better design but to new technologies that can support our imaginations.” In “Cutting Corners,” Kaneko’s tower proposal, the facade presents what he calls “coherent whimsy” and “allied composition” of patterns, taking advantage of two CLT characteristics: the ability to carve cutouts and textures, as well as the aggregation of wood-grain patterns.

Applying digital precision at enormous scales threaded the studio’s speculation; both Goga’s and Kaneko’s exploration of CNC technology, for instance, inspired a broader, more programmatic concept of rearranging entire buildings.

Elif Erez (MArch/MDes-HPDM ’22) traced CLT duality—massive in scale, yet customizable to extreme precision—to its essence: CLT begins its life span as whole wood that is broken into smaller pieces, then stacked and aggregated into CLT form. “I think the CLT blank has a kind of deadpan humor to it,” Erez says. “It is both sheet-like and massive, and when used in the way that one is accustomed to using sheet materials, it does unexpected things with scale and effect.”

In Erez’s house proposal, “Barn för Barn,” an A-frame volume floats atop three smaller volumes, which in turn form the entryways into three separate housing units, divided by two sets of walls that double up to house bathrooms, kitchen, and storage. As the A-frame volume is raised, the ground floor becomes a shaded outdoor space, offering a collective playground for the three housing units above. Forming three different foundations and entrances, CLT blanks read as simultaneously small and enormous.

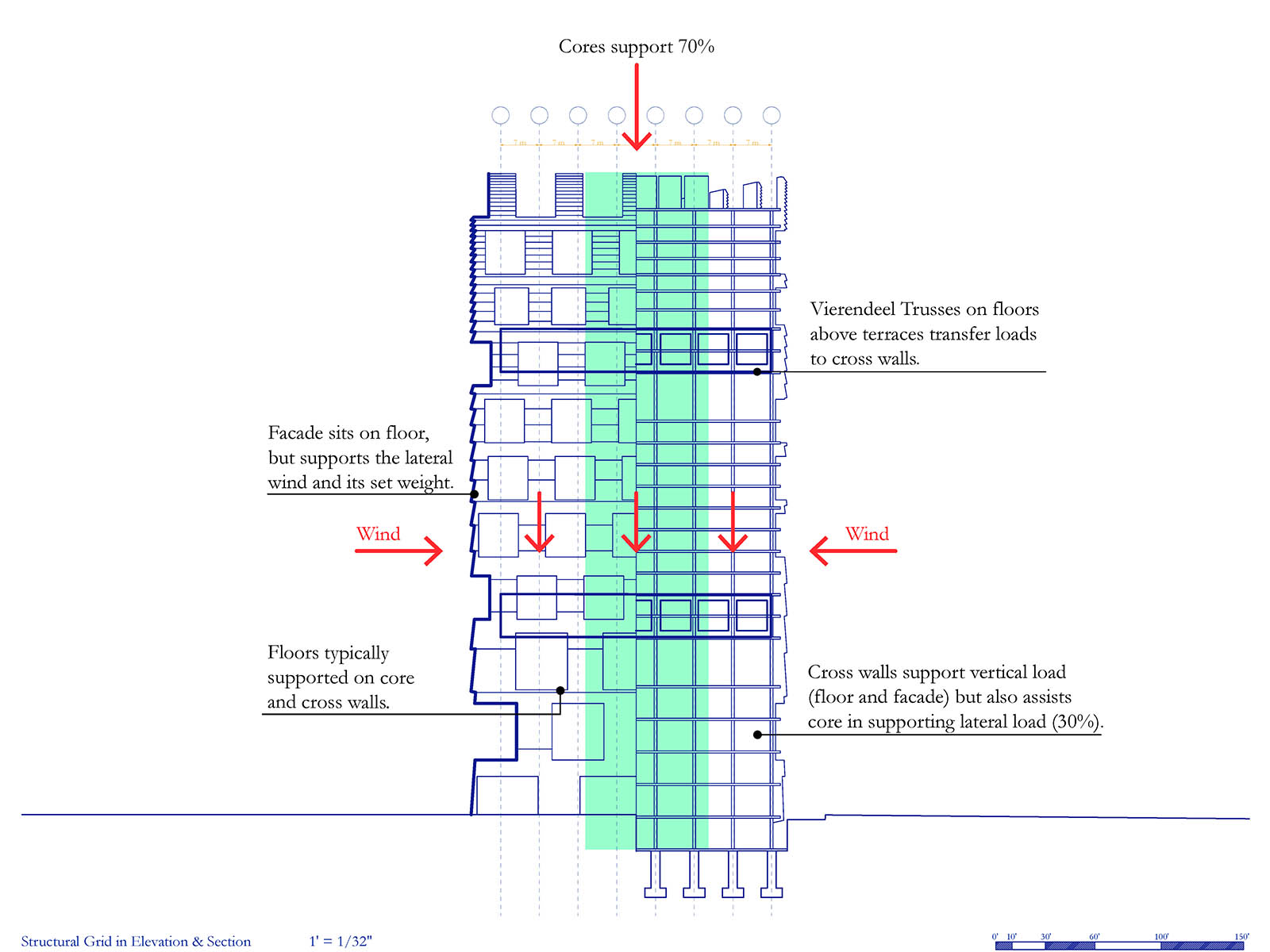

Erez scaled-up “Barn för Barn” for her tower proposal, “Barn, Barn, Barn för Barn,” by designing a floating window grid and three cores that support 70 percent of the tower’s vertical load. Erez applied the same system in the house as she did the tower—CLT as shiplap siding—with the effect appearing gigantic on the tower when compared to its traditional use on houses. Each core of the tower offers a component for collective childcare, while main program is pushed to the building’s edges. The tower, with its brushed metal facade, points just a bit off the perpendicular street grid, creating a triangular orientation. The effect is a tower that offers heterogeneous spatial and programmatic possibilities, and a moment in which the domestic and the urban meet and meld.

Kyat Chin (MArch ’21) probed structural opportunities by designing a tower with a rotational wall system instead of a table. Like others, Chin played first with stacking of CLT blanks and spaces; the four generic table types that resulted were then scaled, stacked, and nested in various configurations, achieving column-free plans to accommodate various programs. One effect, Chin says, is illusions of “rooms within rooms.” Chin cladded the tower’s facade with Canadian cedar shingles and anodized aluminum, blending the domestic and the industrial to reinterpret tower aesthetics.

Like Erez, Daniel Garcia (MArch ’20) presented an askew tower—in his words, “slightly misbehaved”—adapting a generic post-and-beam form into what he describes as an exploration of the post-digital at the tower scale. Intended as an art and design school for Raleigh, Garcia’s tower complicates generic form with the sort of hyper-precise digital editing that CLT construction enables. For his house project, Garcia rearranged the Southern “dog trot” typology to suggest a new form: he adapted the dog trot’s main feature—a long breezeway—and split, then offset, the house along that axis, taking advantage of CLT’s distance-spanning properties. He also stamped the house’s asphalt shingles with an embossed image of wood.

Studio colleague Edward Han (MArch ’21) observes that the ability to color-stain, emboss, and cut patterns into CLT means that it can act as a “contemporary kind of ‘wallpaper’ and ornament.” With aesthetics a central studio consideration, this CLT characteristic offered particular excitement. “For the first time,” Han says, “we have a structural material that can be perfectly cut, mitered, shaped, and fenestrated with a CNC machine, offering endless possibilities.”

Instigating Sustainability, and other Perpetual Effects

In testing CLT against images of domesticity and the American South, the studio questioned how CLT’s unique properties might coalesce in creating a new Effect. Cultural readings interlaced studio proposals: suburban kitsch, log-cabin tectonics, “McMansions,” the traditional Southern porch, and American “bigness” found fresh expression. Traditional stick-framing emerged as an unwitting foil.

“Stick-framing relies on repetition of a particular type, producing houses that look the same: repeated American Dreams of previous centuries,” observes Peeraya Suphasidh (MArch ’20), who recently completed “Wooden House” in Amboise, France. “CLT provides flexibility in terms of customization and gives the ability to do something unique and precise with shorter time.”

One theory behind CLT’s recent recognition has been consumer desire to see more wood. IKEA, for example, structured a 2015 campaign around “wood as lifestyle.” In the studio brief, Bonner and Kara point to IKEA’s Skogsta furniture collection, as well as Sam Jacob’s £30 Plank Scarf, as signaling the image of wood as on-trend. “Wood is often left exposed in mass timber buildings—it doesn’t need to be wrapped or bolstered to meet code—and there is nothing quite so beautiful as large expanses of exposed wood,” writes Vox’s David Roberts. “It is appealing on a primal level, a connection to nature.”

Amid urgent climate concerns, much CLT dialogue circles questions of sustainability. Wood-based buildings can be “carbon sinks,” many argue, absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Experts have speculated on the potential to reduce emissions in the building and construction sector (concrete produces an estimated 5 percent of human-generated carbon dioxide emissions each year). They also expect that it can trim the waste, pollution, and costs associated throughout the construction process—arguing that CLT buildings are simply faster and cleaner to create. And while proponents wrestle with questions about deforestation and supply, Scandinavia has demonstrated that appropriate forestry principles can offset this balance.

The studio also approached broader questions of how, in its application to ongoing issues like housing shortages and affordability, mass timber like CLT might present disruptive solutions. As such, CLT becomes a tool beyond materiality for the architect, inviting if not begetting a recharged agency for architects and a pull for closer collaboration with engineers, builders, artists, and others. Through such synergy, CLT offers designers the chance to not just design new buildings, but to provoke new typologies and ways of working.

“There is potential here for architects and designers to leverage the digital layer of prefabrication to make real-time decisions on cost, performance, and embodied carbon, among others,” says Lily Huang (MArch ’09), Associate Director of Building Innovations at Sidewalk Labs. “Taking an iterative approach can create a more robust process, which leads to better buildings. Mass timber has the potential to catalyze an architectural movement that can define how we design and build buildings in the next 50 years.”

“This is the fascinating fact about CLT: it brings structure and architecture—since their divorce in the modern movement—back together,” observes Khalighy. “This is not a compromise on the autonomy of architecture. On the contrary, it expands the agency of architects and enables them to rethink the structural core of architecture through a collaboration with engineers. To have two instructors in our studio—Jennifer Bonner as an architect and Hanif Kara as an engineer—provided a fantastic environment for us to experience the negotiation between both disciplines, not only from a practical standpoint, but as an intellectual activity.”

“Mass Timber and the Scandinavian Effect” was led by Jennifer Bonner, Associate Professor of Architecture, and Hanif Kara, Professor in Practice of Architectural Technology, with Teaching Associate Nelson Byun (MArch ’15). The studio’s February 2020 site visit was generously supported by Sven Tyréns Trust.