Three Student Proposals Addressing the National Housing Crisis Place at the 2021 Hack-A-House Competition

Proposals developed by three groups of Harvard Graduate School of DesignGSD students were recently recognized at the 2021 Hack-A-House competition . Hosted by Ivory Innovations and co-sponsored by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University, the annual 24-hour charette-style competition seeks solutions to the national housing crisis. Once given a prompt, teams of one to five students have 24 hours to submit an innovative proposal for a problem directly affecting housing affordability in one of three categories: Finance, Regulatory & Reform, or Construction & Design. The solutions seek to create economic opportunities for vulnerable populations in the participants’ communities and beyond.

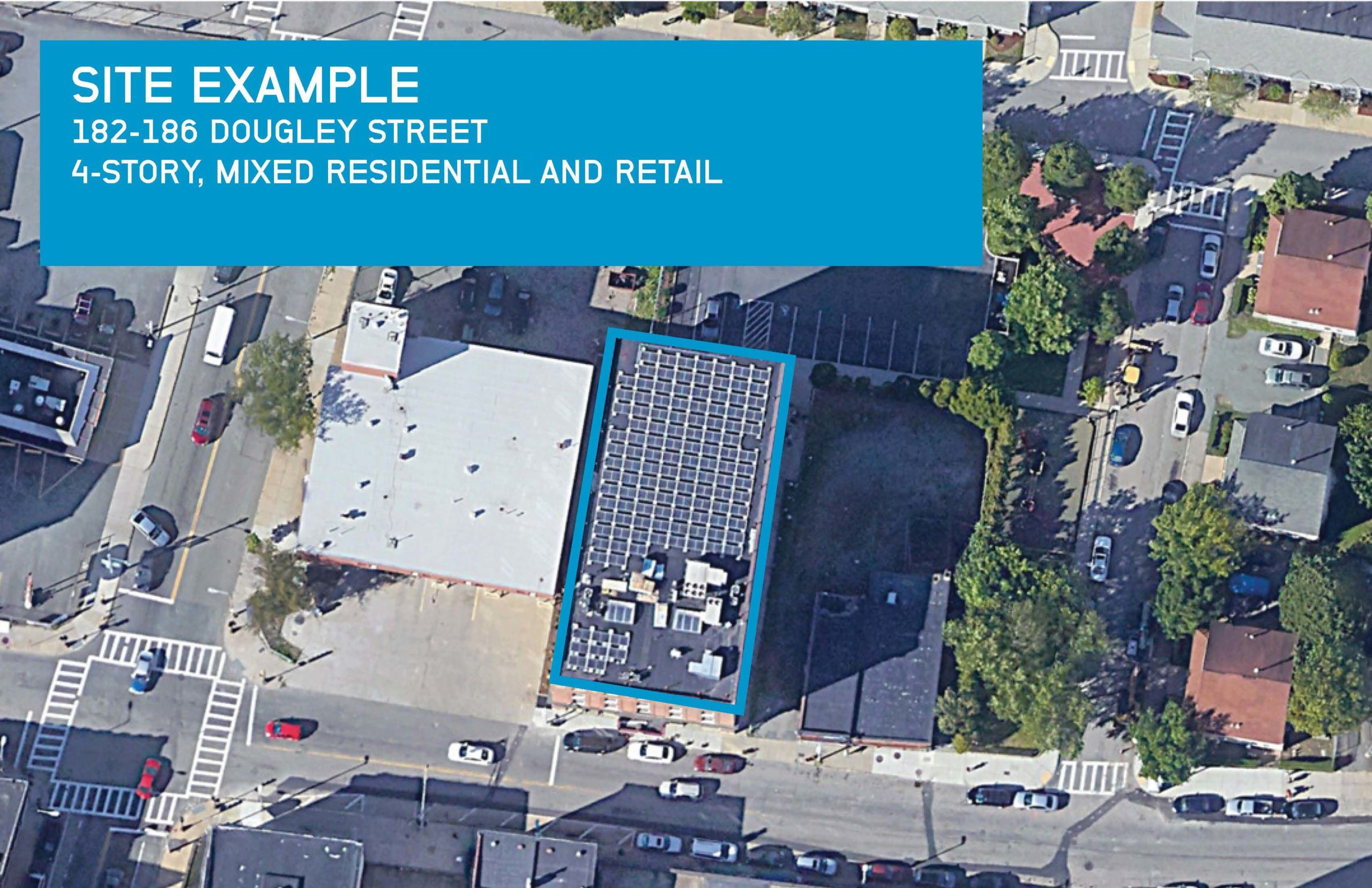

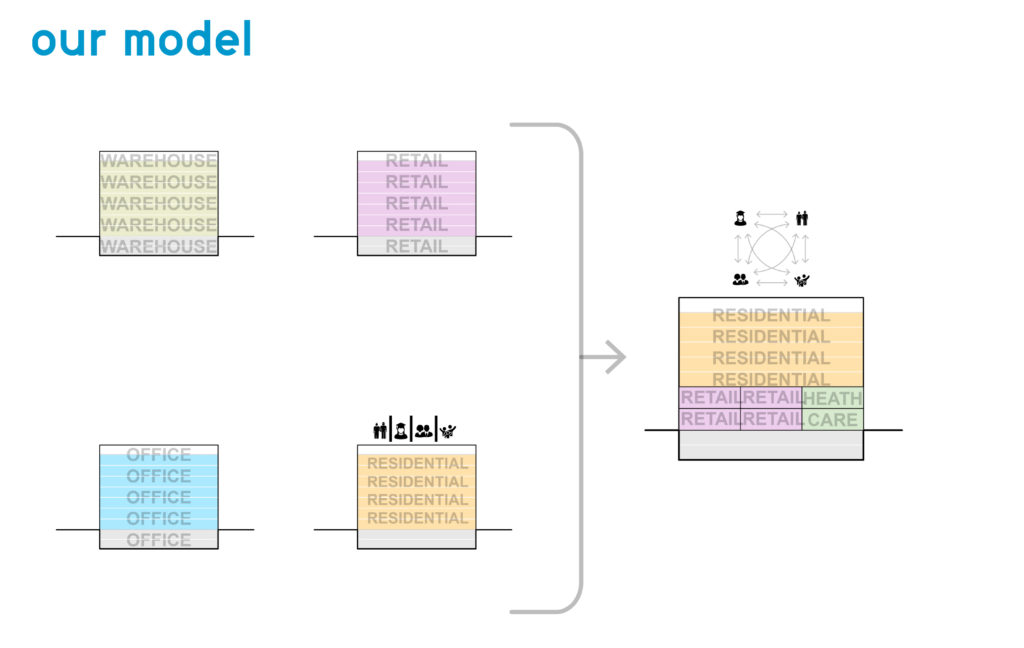

“Legacy Living: A Pathway to Affordable Multi-Generational Homeownership” by Miguel Lantigua-Inoa (MArch II ’23), Margaux Wheelock-Shew (MArch II ’23), Adam Yarnell (MDes EE ’22), and Arami Matevosyan (MDes REBE ’22) was the winner in the Policy & Regulatory Reform category. The team addressed the lack of affordable elderly housing, the projected shortage of home health aides, and the increasing percentage of adults over the age of 65 in the United States. In response, the project proposes the development of mixed-use, multigenerational housing that includes healthcare services alongside traditional retail outlets.

Watch the team’s video presentation .

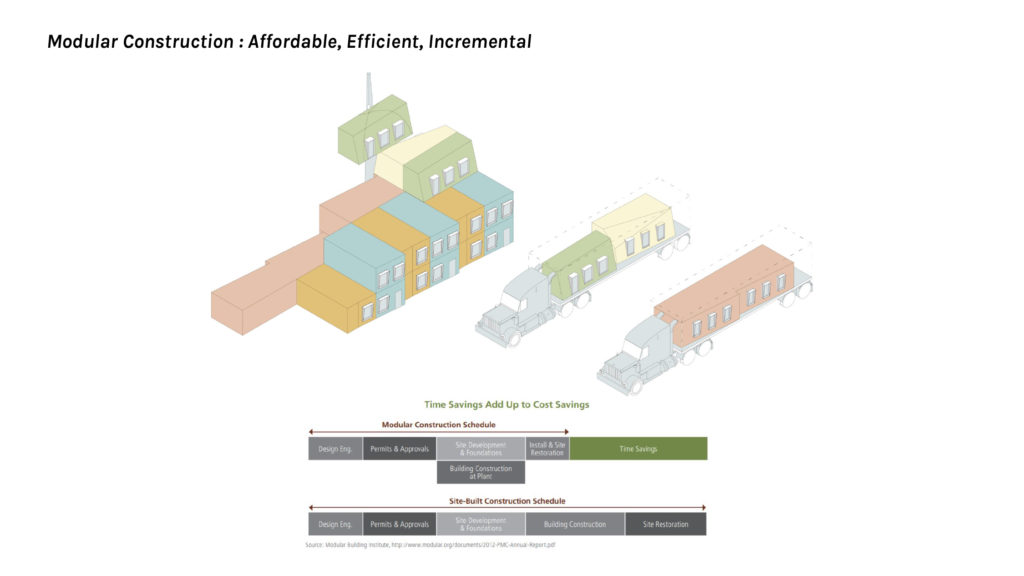

“Union Squared: A Housing Typology for ALL Households” by Cassie Gomes (MArch I ’22) and Angela Blume (MArch I ’22) was a runner-up in the Construction & Design category. The proposed project seeks to make homeownership affordable to 30 percent of area medium income (AMI) households by providing a “diverse assortment of housing types for varying household arrangements” through a “catalogue of parts that can be used to expand a house over time.” The team identified modular construction as an affordable and efficient method that can expand incrementally based on household needs.

Watch the team’s video presentation .

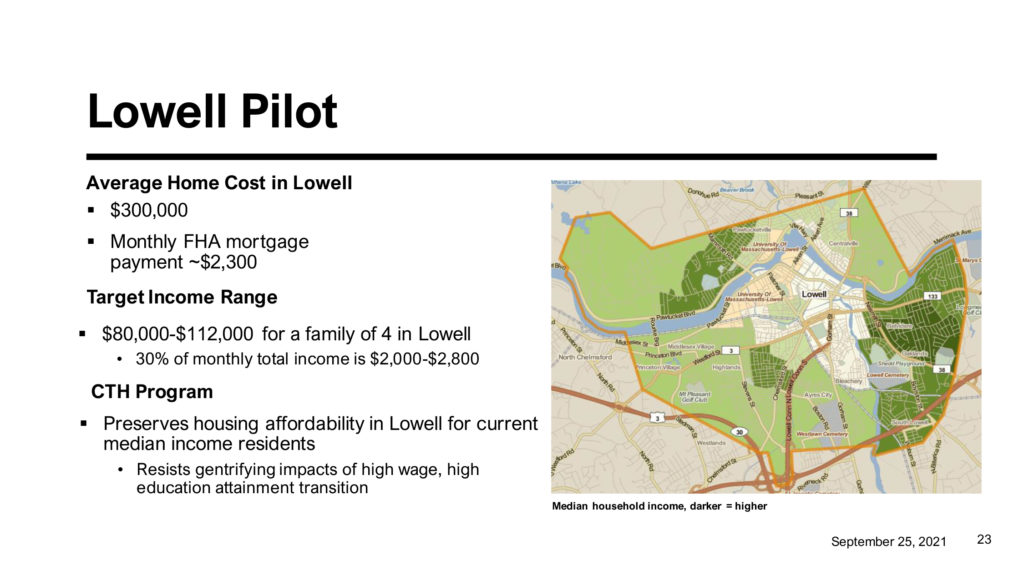

“Assumable Mortgage Financing: Affordable Equity-Building in Gateway Cities” by Zoe Iacovino (MUP/MPP ’23), Claire Tham (MUP ’23), Chadwick Reed (MUP ’22), and Allison McIntyre (Tufts University) was a runner-up in the Policy & Regulatory Reform category. The project seeks to combat gentrification in cities on the peripheries of major metro areas, like Lowell, MA, that are facing population growth in the wake of mass adoption of work-from-home policies due to COVID. Team Undecided proposes that ARPA (American Rescue Plan Act) funds are used to originate assumable mortgages on homes in neighborhoods subject to gentrification to allow an affordable path to homeownership for lower income residents in Lowell and beyond.

Watch the team’s video presentation .

This is the second year in a row that GSD students have placed in the annual Hack-A-House Competition. In 2020, Iacovino, Reed, Ryan Johnson (MUP ’22), and Gianina Yumul (MUP ’22) won the competition’s grand prize in the Policy & Regulatory Reform category for their project, “Parking Lot Potential: Converting excess parking to affordable manufactured housing in a post-COVID world.”

Faculty-led KARAMUK KUO Wins Competition for New Research and Laboratory Building in Basel

KARAMUK KUO , the Zurich-based architecture office led by Ünal Karamuk and GSD Assistant Professor in Practice Jeannette Kuo, has won the competition to construct a new laboratory and research building in the center of Basel, Switzerland. The competition was conducted anonymously, with 48 international firms participating in the first round and 13 firms selected for the competition. Utilizing innovative hybrid timber and a concrete structure, the project incorporates flexibility, durability, and sustainability. According to a press release by the Building Department of Basel, “The jury, chaired by city architect Beat Aeberhard, unanimously voted for KARAMUK KUO.”

The 32,000-square-meter (350,000-square-foot) building is the anchor in a masterplan by Herzog & de Meuron that transforms the industrial Rosental Mitte area into an open and vibrant science campus. With leasable lab spaces, a science lounge, and teaching and conference spaces, the building will be a hub for scientific exchange, bolstering the city’s biochemical and pharmaceutical industries. The University of Basel’s chemistry department is expected to be the primary tenant and will occupy half of the new laboratory space for the next decade.

Read a press release about the project from the City of Basel.

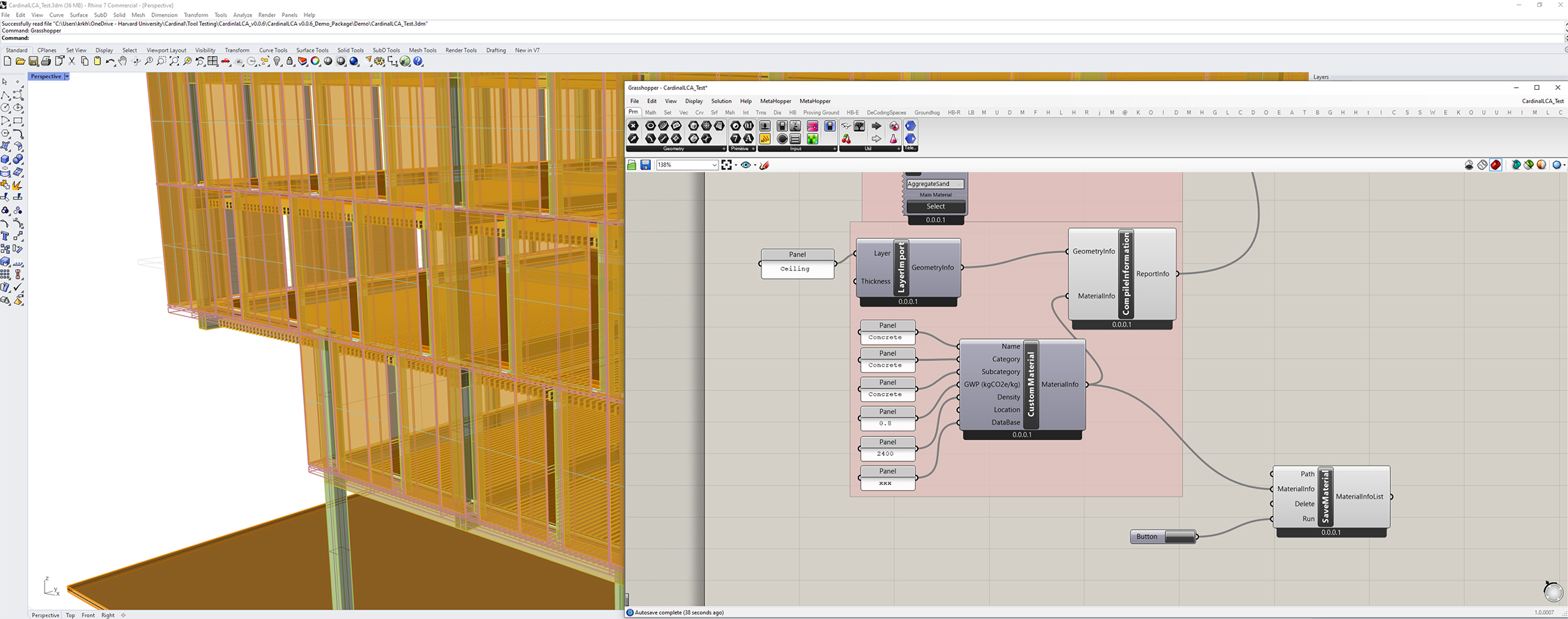

Student-Developed Environmental-Impact Assessment Tool Released for Grasshopper

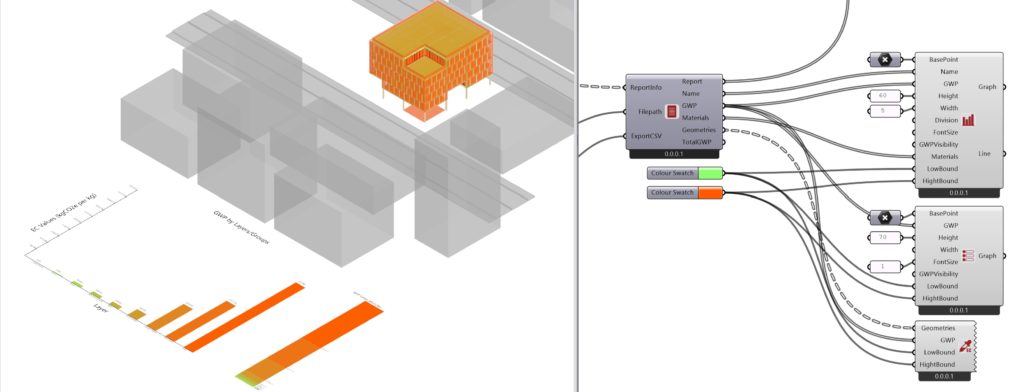

Cardinal LCA , an early-stage environmental-impact assessment tool developed by Jessica Chen (MDes EE ’22) and Kritika Kharbanda (MDes EE ’23), was recently released as a Grasshopper plug-in. Designed for non-experts, the tool allows architects to analyze the environmental costs of material decisions in the early stages of the design process.

The framework for the tool was formed in “Advanced Topics on Embodied Carbon in Buildings,” a fall 2020 seminar led by Jonathan Grinham, lecturer in architecture and senior research associate. The course provided “an open arena to address the environmental and human impacts of material management in the built environment through tangible, design-led learning.”

Over the summer, Chen and Kharbanda created an external team to develop their GSD research into a Grasshopper plug-in. “Currently, the product stages (A1-A3) are accounted for in the GWP [Global Warming Potential] calculation, and the study boundary includes early design stage elements in a Rhino model—the structure, envelope, and interior assemblies,” explain Chen and Kharbanda. “The tool analyzes the embodied impacts (GWP in kgCO2e) using the EC3 (US) and ICE 2019 (UK) databases.”

Users have the option to input their own Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) data and develop their own library, and the tool’s outputs are shared through Excel. The files include values, 2D graphs, and 3D mapping highlighting elements with the lowest and highest GWP contributions.

“Using Cardinal LCA in early stages allows for quick estimation, with more carbon capture benefits,” note Chen and Kharbanda. “It is easily integrated into the architectural workflow and architects save time by performing real-time visualizations. Further, architects can exercise the flexibility of controlling precision by using average or specific values.”

In September, the Cardinal LCA team received the 6th Annual MDes R&D Award to present their work at the American Center for Life Cycle Assessment (ACLCA) 2021 Conference .

Cardinal LCA can be downloaded from Food4Rhino .

Anne Anlin Cheng on Discussing Beauty and Aesthetics to Dismantle Systems of Oppression

In her latest book, Ornamentalism, multidisciplinary scholar and Princeton professor Anne Anlin Cheng focuses on the urgent, albeit often overlooked subject of Asiatic feminism. Intending to fill a conceptual void, Cheng addresses the centuries-old Western tradition of equating Asiatic femininity and excessive ornamentality. “Ornamentalism, for me, is not just about having a person made into a thing, which is oftentimes something that we think of around the history of race. But it is also about the condition of life and possible intimacy within objectness. It is about how personhood might be indebted to objects,” she said during her recent lecture at the GSD: “Monsters, Cyborgs, and Vases: Apparitions of the Yellow Woman.”

Cheng describes ornamentalism as a “theory of being.” It focuses on the means by which the personhood of the “Yellow Woman” is construed through the artificial and the ornamental. “These processes happen more often and more visibly than we think,” she explained in the lecture, “through the minute, the sartorial, the decorative, the prosthetic, and design.” In a recent conversation over Zoom, she reflected further on ornamentalism, the importance of finding an unorthodox vocabulary to examine racialized gender oppression—especially in the case of the Yellow Woman—and why we must radically reconsider what is beauty and what is human in a broken world.

What inspired you to begin writing about the Yellow Woman?

The issue has been at the back of my mind for a very long time. But the need to write a book and do the work came after I saw an exhibit at the Met in 2017—China: Through the Looking Glass. I was stunned by its unabashed Orientalism. At the same time, I also found this show mesmerizing. Not only because it was so sensorially rich, but also because of the intense objectification and the insistence of Asiatic femininity as an idea and presence in the show.

I read all of these articles about it (there were a lot of protests). And the thing that struck me was that we’re looking at this expansive history of the representation of Asiatic femininity, but the way we have to talk about it is incredibly limited. I mean, critiques of commodification, objectification, or fetishization are all accurate critiques. But we have been saying the same thing for decades and we should have a much richer vocabulary to think about these issues. This phenomenon is what got me started on this project. And once I delved into it, it became very clear to me that the association between Asiatic femininity and ornamentality is philosophically, artistically, and representationally, deep and expansive.

How do you define the Yellow Woman?

I find the term very painful. I’m using it deliberately because I wanted to denote the racialization of Asiatic women, one that is quite obvious and yet very underdiscussed. I’m also talking about a history of representation that is completely indifferent to what “Asian” or “Asian American” really means. What I’m talking about is an American view of Asiatic femininity.

You’ve spoken about invisibility as a form of oppression. What does that look like in practice?

I think Asian Americans and Asians in America suffer from an ambivalence problem. They are invisible since they rarely fall into the racial calculus unless a crisis happens (like a virus). They are often seen as invisible through discourses such as the model minority discourse, where people say, “They’re all doctors and lawyers anyway, so what do we care?” And at the same time, they’re hypervisible as subjects of difference. They look racially different. And this is part of the reason why there’s been such a spike in anti-Asian violence across the country. At the same time, Asian American women are super visible because of what is considered an aesthetic privilege, while they’re also being evacuated under this language. We think of oppression as something embodied—as it can often be— but it is also about erasure, a kind of violence that’s harder to talk about because it’s not as visible.

You’ve said that you view ornamentalism as a form of survival; can you expand on that?

I think part of the problem with naming something as a stereotype is that in naming it, oftentimes there’s a kind of assumption that we know it only too well: “This thing again. Terrible. We know it. Let’s turn away from it.” And I think when we do that, we fail to see all kinds of alternative possibilities for agency and what other kinds of survival might be at stake. And so my approach is I don’t want to simply decry objectification. I want to first acknowledge it. I want to acknowledge its profound philosophic and historic material history and imaginative history. But then I want to go on to ask what happens to the person that is actually still living as a person underneath that objectification. So I think what we need is something in between—a much more nuanced and expansive look at what constitutes surviving. If the Asiatic woman has lived for thousands of years under the terms of this objectification, how do we think about her as actually continuing to have a certain form of ontology?

During your lecture, you said, “We must radically reconsider what is beauty in a broken world, as well as what is human.” Why do you think discussions about aesthetics and beauty are essential to subvert systems of oppression?

They don’t usually go together, right? Aesthetics and politics. But the aesthetic often expresses the political, and it can be a place to undo the political in certain ways. For instance, there are areas in which beauty remains uncontested. That is to say, I can talk about the beauty of a flower, a painting, or a small child, without too many people getting upset. They might not agree, but no one is going to come and yell at me about it. Yet, when it comes to a racialized person, and particularly women, beauty is really fraught. It is something they’re historically excluded from. And our instinct is to correct it by offering a positive stereotype (e.g., “Black is beautiful”), but that doesn’t challenge the fundamental logic. I’m not interested in judging who is or isn’t beautiful. I’m interested in how beauty is a site of value and affirmation and how that gets inflicted differently when it comes to race and gender.

I also think aesthetics—particularly art and literature—have a way of articulating certain things left out in legal or sociological discourses about race. Aesthetics is a language about the ineffable and the contradictory. It makes room for the historical, the imaginative, and the phantasmagoric. What people don’t realize is that race and gender are such complicated phenomenons that straddle the material and immaterial, that we desperately need the realm of art and literature to help with a vocabulary.

*This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Sara Zewde Collaborates with Adjaye Associates on Affordable Housing Redevelopment in Brooklyn

Underutilized land in Brooklyn is slated to become home to hundreds of units of affordable housing surrounded by abundant public green space, and the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Sara Zewde will helm the design.

Zewde and her Harlem-based Studio Zewde will collaborate with Sir David Adjaye and Adjaye Associates to reshape 7.2 acres of the Kingsboro Psychiatric Center campus in East Flatbush, Brooklyn. The redevelopment of such a sizable swath of land is part of New York State’s $1.4-billion Vital Brooklyn initiative. Launched in 2017, the initiative seeks to address inequities in some of Central Brooklyn’s most underserved neighborhoods, offering development plans scaffolded by eight integrated goals: open space and recreation, healthy food, education, economic empowerment, community-based violence prevention, community-based health care, affordable housing, and resiliency.

Zewde and Adjaye’s proposal for Kingsboro—chosen via a design competition—calls for 900 units of affordable and supportive housing as well as senior housing, with a set of apartments reserved for homeownership programs. The proposal also includes two new, state-of-the-art homeless shelters. Responding to Central Brooklyn’s status as one of New York’s most extreme food deserts, Zewde and Adjaye have grounded their proposal with a grocery store, which is expected to serve as a core commercial center. A 7,000-square-foot community hub will include a workforce training center, performance space, fitness facilities, classrooms, an urban farm and greenhouse, and other dedicated community spaces. There will be free WiFi access throughout.

“The redevelopment of a portion of Kingsboro Psychiatric Center will bring more affordable housing to a community that desperately needs it, and the opportunities for healthier and greener living,” says Eric Adams, Brooklyn borough president and Democratic nominee in the 2021 New York City mayoral election. “As someone who has long promoted the need to overhaul our local food system, I am particularly glad to see that this project will include urban farming opportunities to connect people to healthy foods and activities.”

With Zewde and Adjaye spearheading design, the project more broadly will be led by a development team composed of Almat Urban, Breaking Ground, Brooklyn Community Services, the Center for Urban Community Services, Douglaston Development, Jobe Development, and the Velez Organization. Next steps for designers and developers will include community engagement work with local stakeholders and community boards in the coming months. The project is expected to be completed in about four years.

Julie Bargmann (MLA’ 87) wins inaugural Cornelia Hahn Oberlander International Landscape Architecture Prize

The Oberlander Prize, an initiative of The Cultural Landscape Foundation, includes a $100,000 award and two years of public engagement activities focused on the laureate and landscape architecture

The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) has named Julie Bargmann (MLA ’87) the winner of the inaugural Cornelia Hahn Oberlander International Landscape Architecture Prize (Oberlander Prize), a biennial honor that includes a $100,000 award and two years of public engagement activities focused on the laureate’s work and landscape architecture more broadly. The Prize is named for the late landscape architect Cornelia Hahn Oberlander (BLA ’47) and, according to TCLF, is bestowed on a recipient who is “exceptionally talented, creative, courageous, and visionary” and has “a significant body of built work that exemplifies the art of landscape architecture.”

Julie Bargmann (MLA ’87), 2021 Oberlander Prize laureate. Photo ©Barrett Doherty courtesy The Cultural Landscape Foundation

Coming Soon: Harvard Design Magazine #49: Publics questions how public spaces operate in a fragmented social and political environment

Harvard Design Magazine relaunched with March 2021’s Harvard Design Magazine 48: America, an issue that interrogated the essence and the history of the United States. This November, the magazine returns with another timely inquiry, one that has both rigor and curiosity at its center. Harvard Design Magazine 49: Publics questions how public spaces—the physical, the cultural, and the theoretical—operate in a fragmented social and political environment, both in the US and abroad. Guest editors Anita Berrizbeitia and Diane E. Davis convene leading public intellectuals, scholars, and practitioners in architecture, urban planning, landscape design, law, and the social sciences and humanities to investigate design theories and outcomes percolating at the heart of national and global cultural discourse. They ponder the fate of “the public” in a world where xenophobic thinking and challenges to communal responsibility are, as the editors observe, becoming ever more dominant, and in which individualism poses a corrosive challenge to collectivity and unity. This issue integrates theoretical and thematic debates, including over who holds the power to define what is “public,” what roles class, ethnicity, and other identity matrices play in the concept of “the public,” and how the core idea of “a public” may survive—or atrophy—given looming environmental crises and deepening political and economic divisions. Publics enriches this dialogue with spatial and material looks at how the public is constructed and shaped through design projects and cultural production. Berrizbeitia and Davis contribute unique, complementary lenses to this well-timed inquiry. Chair of the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Department of Landscape Architecture, Berrizbeitia has led studios investigating innovative approaches to the conceptualization of public space, especially on sites where urbanism, globalization, and local cultural conditions intersect. Trained as a sociologist, Davis chaired the GSD’s Department of Urban Planning and Design, with research interests covering the relations between urbanization and national development, comparative urban governance, socio-spatial practice in conflict cities, urban violence, and new territorial manifestations of sovereignty. Each has published a wide array of books, journal articles, and other editorial work. Collaborating with Editorial Director Julie Cirelli and Publications Manager Meghan Ryan Sandberg, Berrizbeitia and Davis invited design observers and critics from within the GSD and beyond. The magazine’s introductory essays include contributions from Walter Hood, Sara Zewde, and architectural collaborative Assemble. The heart of Publics applies the immersive editorial structure and spatial rhythm established by its predecessor. In “Sites,” Toni L. Griffin muses on “South Side Land Narratives: The Lost Histories and Hidden Joys of Black Chicago.” “Spaces” offers observations from Frida Escobedo, Ali Madanipour, and others, analyzing what constitutes public space. “Scales” investigates ways in which the concept and shapes of “the public” interact with shared cultural concerns, including environmental justice, public health, and Indigenous land rights. And “Subjects” interrogates the very definition of “public”—especially the people for whom designers shape and create space. Publics concludes with a call-and-response segment, in which contributors including Christopher Hawthorne, Lizabeth Cohen, and others respond to a provocative prompt: “What is the most important public space worth preserving now?” Answers range from city sidewalks to Boston’s Franklin Park, to the Mississippi River Gathering Grounds, to your own backyard. The editorial structure Cirelli introduced with America provides an avenue through which design observers and others can constructively and collaboratively explore complicated issues and themes. Cirelli continues to refine the magazine’s voice, design, and feel, and she explains that the guest-editor model presents an opportunity to infuse fresh and diverse direction and voice in each issue. “By exploring what constitutes a public, Anita and Diane have struck at one of the fundamental questions of our moment: What are our rights, as human bodies on this earth? What belongs to us? What should belong to us, but doesn’t?” says Cirelli. “The scholars and practitioners we’ve invited to explore notions of the public have demonstrated how health, education, housing, access to food and clean water, and the right to advocate for oneself and one’s community all have a common thread. And as we pull that thread, the mechanisms of power and privilege are revealed. ” Harvard Design Magazine is an architecture and design magazine that probes at the reaches of design and its reciprocal influence on contemporary culture and life. Published twice a year and helmed by Editorial Director Julie Cirelli at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, Harvard Design Magazine invites guest editors to consider design through an interdisciplinary lens, resulting in unique perspectives by an international group of architects, designers, students, academics, and artists. For current and back issues, as well as subscription information and stockists, visit the Harvard Design Magazine website.In Inaugural Cycle, REA Fund Supports Diverse Projects United by Pursuit of Equity and Anti-Racism

In spring 2021, the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s Office of Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging introduced the Racial Equity and Anti-Racism Fund (REA Fund), an initiative aimed at raising awareness of how race, racism, and racial injustice affect society—especially by and through design professions—and to promote a culture of anti-racism at the GSD. The inaugural REA Fund projects, ranging from the individual to the institutional, have come to fruition in recent months, illustrating the diversity and depth of inquiry the fund has supported. “The REA Fund has been a vehicle to bring the GSD together,” says Naisha Bradley, Chief Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging Officer at the GSD. “Over this first year we’ve had strong community input and were able to support initiatives from multiple constituencies at the school. Whether it was through one-time initiatives, community-wide programming, or semester-long classes, the REA Fund has created an innovative pathway for us to incorporate anti-racism into our community fabric and help create a GSD where many voices can be heard and all people can thrive.” The fund has sought stakeholders from around the GSD to consider the sorts of programming and dialogue that has been missing, and to suggest solutions. It has also prioritized the need for immediate or accelerated change alongside longer term, ongoing work connecting design and anti-racist practice.Whether it was through one-time initiatives, community-wide programming, or semester-long classes, the REA Fund has created an innovative pathway for us to incorporate anti-racism into our community fabric and help create a GSD where many voices can be heard and all people can thrive.

Naisha Bradley, Chief Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging Officer

Technology as Racial Justice

“Access to technology, like the internet and the devices through which we interact with it, are susceptible to the racial disparities that affect our physical environments and social structures,” says Omotara Oluwafemi (MArch ’22). “In creating digital spaces, we have to begin to reinterpret accessibility and equity as terms that also apply to the virtual realm.” Oluwafemi collaborated with Idael Cárdenas (MArch ’22) to plan the February 22 panel discussion “The Use of Technology in Design as an Avenue Towards Racial Justice,” focusing on digitally driven design narratives, technology, and mechanisms and how these dynamics intersect with questions and matters of race in design. With REA Fund support, organizers convened Michelle Chang and Marisa Parham, as well as two moderators, for conversations around how to ground considerations of equity and community empowerment amid ongoing digital innovation and growth.

“This past year has been especially challenging for BIPOC designers, as a resurgence of white supremacy and police violence negatively affected our most vulnerable communities,” says Cárdenas. “In this heightened atmosphere, Tara and I felt that it was critical to provide a platform where diverse voices can discuss these issues in parallel with how it affects the built environment.”

Through the panel, Chang and Parham observed how the digital universe can be a liberating space, but also one whose effects can vary widely based on each user’s identity. The context of the pandemic and virtual pedagogy threaded the conversation: panelists took up the intersections between technology and narrative, and how means and formats of communication and idea-sharing can shape methods of teaching and designing.

Parham has long positioned technology and digital media as fundamental to the creation of narrative and dialogue. During the panel, she shared her multimedia project “.break .dance”—a “time-based web experience,” she explained—that gathers various stories and voices, presenting them via an unfolding user-interface.

Like other projects and phenomena discussed during the panel, “.break. dance.” demonstrates how BIPOC voices and experiences, so often minimized or overlooked, can find particular resonance in the digital world. “Through technology and digital media, we are able to connect with communities across the globe to empower our local and domestic efforts for equity,” Oluwafemi says. “Digital media has given us access to histories and stories that we are not taught in school. We are able to fill in the gaps in our institutional knowledge, as seen through efforts like [anti-racist design school] Dark Matter University.”

Oluwafemi collaborated with Idael Cárdenas (MArch ’22) to plan the February 22 panel discussion “The Use of Technology in Design as an Avenue Towards Racial Justice,” focusing on digitally driven design narratives, technology, and mechanisms and how these dynamics intersect with questions and matters of race in design. With REA Fund support, organizers convened Michelle Chang and Marisa Parham, as well as two moderators, for conversations around how to ground considerations of equity and community empowerment amid ongoing digital innovation and growth.

“This past year has been especially challenging for BIPOC designers, as a resurgence of white supremacy and police violence negatively affected our most vulnerable communities,” says Cárdenas. “In this heightened atmosphere, Tara and I felt that it was critical to provide a platform where diverse voices can discuss these issues in parallel with how it affects the built environment.”

Through the panel, Chang and Parham observed how the digital universe can be a liberating space, but also one whose effects can vary widely based on each user’s identity. The context of the pandemic and virtual pedagogy threaded the conversation: panelists took up the intersections between technology and narrative, and how means and formats of communication and idea-sharing can shape methods of teaching and designing.

Parham has long positioned technology and digital media as fundamental to the creation of narrative and dialogue. During the panel, she shared her multimedia project “.break .dance”—a “time-based web experience,” she explained—that gathers various stories and voices, presenting them via an unfolding user-interface.

Like other projects and phenomena discussed during the panel, “.break. dance.” demonstrates how BIPOC voices and experiences, so often minimized or overlooked, can find particular resonance in the digital world. “Through technology and digital media, we are able to connect with communities across the globe to empower our local and domestic efforts for equity,” Oluwafemi says. “Digital media has given us access to histories and stories that we are not taught in school. We are able to fill in the gaps in our institutional knowledge, as seen through efforts like [anti-racist design school] Dark Matter University.”

A Moratorium on New Construction to Disrupt the Design Paradigm

Assistant Professor of Urban Design Charlotte Malterre-Barthes has shaped pedagogy and research around urgent aspects of global urbanization, addressing questions of how disadvantaged communities can gain access to political and economic resources as well as to ecological and social justice. Last spring, Malterre-Barthes engaged the REA Fund to organize the April 23 panel discussion “Stop Construction? A Global Moratorium on New Construction” with panelists Arno Brandlhuber, Cynthia Deng, Elif Erez, Noboru Kawagishi, Omar Nagati, Sarah Nichols, Beth Stryker, and Ilze Wolff. Malterre-Barthes moderated a conversation in which designers questioned the role of construction in generating and perpetuating social and ecological injustice, as well as alternative growth models and approaches that eschew construction as a primary force. She notes that suggesting the possibility of a moratorium on new construction was bound to stir debate, especially given that designing and creating new spaces are foundational to the design fields.

Panelists at “Roundtable 01. Stop Construction?” questioned common definitions of architecture and design, as well as assumed models for growth and development.

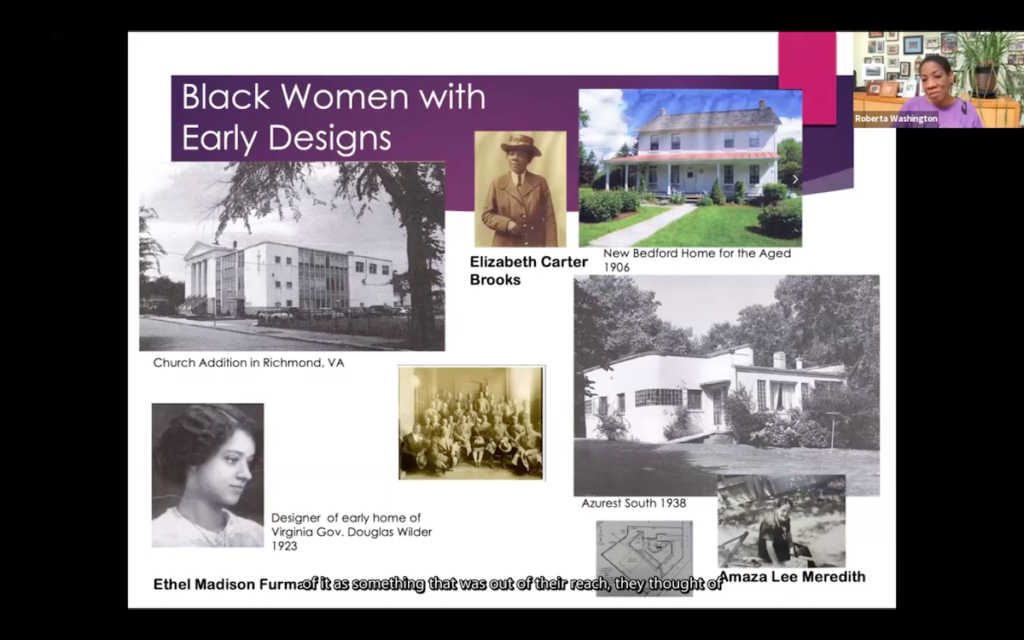

Elevating Design’s “Hidden Figures,” and Finding New Ways of Creating and Sharing Knowledge

As an architect, urbanist, and activist, Hansy Better Barraza has studied the complexities of how identity and design intersect. Following years of research, as well as the cultural tumult that marked 2020, Better Barraza conceptualized the Spring 2021 Harvard GSD seminar “Hidden Figures: The City, Architecture and the Construction of Race and Gender” as a dual opportunity: an effort to reveal designers and communities who have been historically diminished or overlooked, as well as a disruptive moment in which to question how design knowledge and pedagogy—their production and dissemination—may be complicit in such inequities. Better Barraza placed co-creation at the heart of the course’s mission—a value and an act that is fundamental to her ongoing design practice and research. She saw co-creation as an opportunity to challenge the traditional model of professor-to-student knowledge distribution, seeking instead to generate knowledge holistically. Throughout the seminar, Better Barraza encouraged students to engage their own ethnic and geographical identities as touchstones, and to seek connections between the “Hidden Figures” seminar and their concurrent studio work. Collaborative pedagogy, Better Barraza believes, can lead to a fairer and more complete understanding of design’s history.[The REA Fund] requires the GSD community to pause and take stock of where we are now and imagine what could be possible. By distributing resources to faculty, researchers, staff, and students alike, we lower barriers and empower everyone to be a leader in cultivating a GSD for all.

Esther Weathers, Associate Director of Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging

¡…. A La Calle!

Latin GSD’s spring symposium, ¡…a la calle! Art, Design, and Discourse in times of turmoil in Latin(x) America, invited artists, designers, and scholars to present and speculate about the current and future state of Latinx creative practices. Participants discussed critical practices and action models via social agency, art, and design. “The current socio-political instability in Latin American regions and the criminalization of Latinx communities in the US invites us all to find physical and virtual spaces for reflection, action, and solidarity through the lens of art, architecture, and design,” writes Latin GSD. With REA Fund support, Latin GSD invited Latinx leaders in the design fields and other designers to join this event. Speakers included Regina José Galindo, Noemí Segarra Ramírez, Ronald Rael, and Delight Lab.

“The current socio-political instability in Latin American regions and the criminalization of Latinx communities in the US invites us all to find physical and virtual spaces for reflection, action, and solidarity through the lens of art, architecture, and design,” writes Latin GSD. With REA Fund support, Latin GSD invited Latinx leaders in the design fields and other designers to join this event. Speakers included Regina José Galindo, Noemí Segarra Ramírez, Ronald Rael, and Delight Lab.

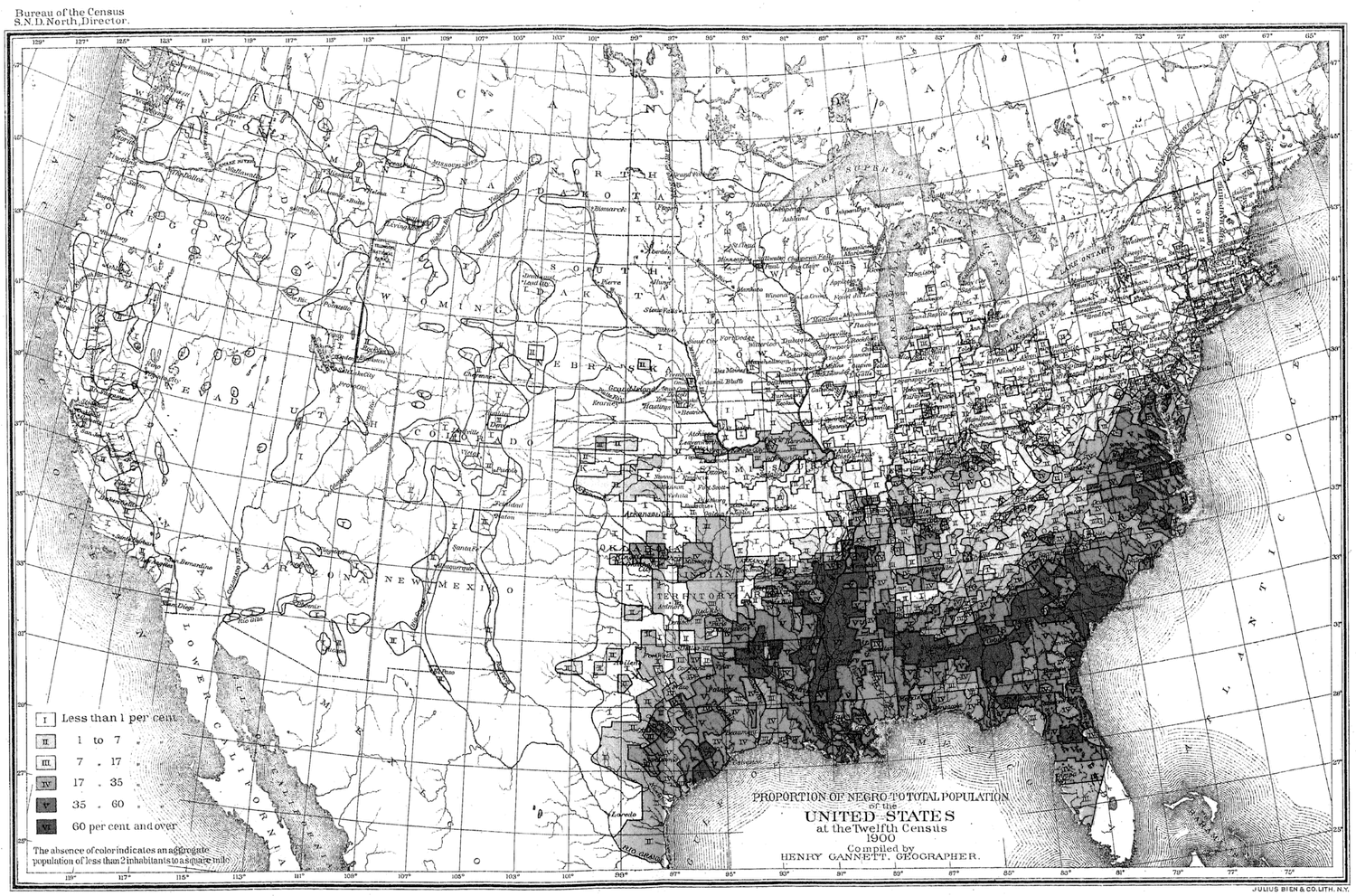

Shifting Power in the Black Belt

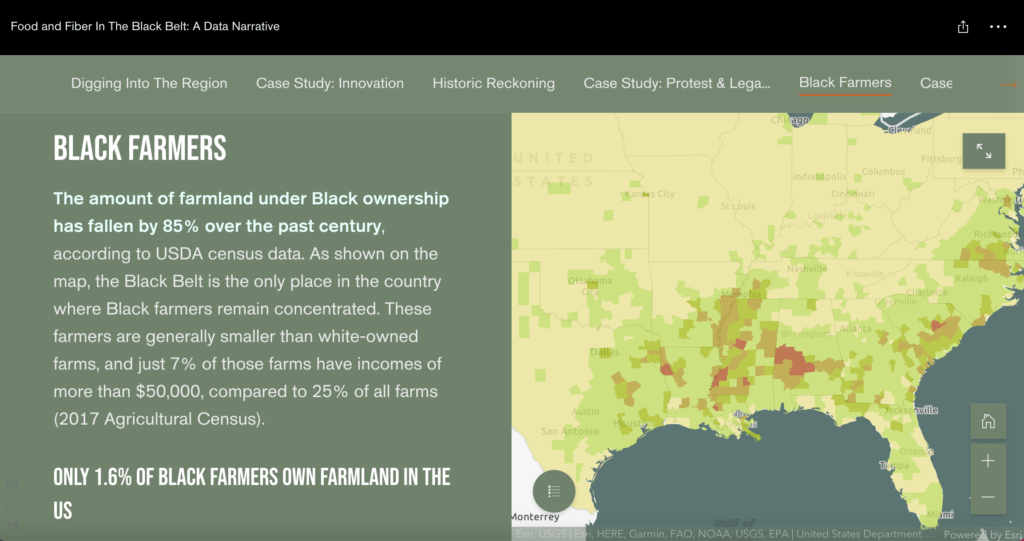

While a lecturer in urban planning and design, Lily Song helped organize CoDesign, an effort to strengthen links between teaching, research, practice, and activism and to foster applied projects within the GSD and collaborative opportunities beyond. The project intrigued 2016 Loeb Fellow Euneika Rogers-Sipp, an artist, activist, and CEO and founder of Atlanta’s Destination Design School of Agricultural Estates (DDSAE). Noting a mutual commitment to promoting anti-racist practice and epistemology throughout design, Rogers-Sipp invited Song to collaborate on a research seminar focused on the so-called Black Belt region—a band of the American South stretching from Virginia to Texas in which plantations and slavery were endemic. A full-service art and community-design school that takes the Black Belt region of Georgia as its campus and canvas, DDSAE has 10 partner-site locations. The school aims to “celebrate and reimagine the profound culture and history of food, farming and hospitality through the creation of a Black Belt Reparations Design Residency and education center that can serve as a replicable model with a national ripple effect.” Song says, “Having studied with Black radical thinkers and activists like Robert Allen and Phil Thompson, who look to the Black Belt as the cradle of American freedom movements and cultural traditions, I received this as a real honor.” Song and Rogers-Sipp’s Spring 2021 field lab arose amid ongoing dialogue over the proposed Green New Deal, a congressional resolution to combat climate change and generate jobs in clean-energy industries. The CoDesign Field Lab research seminar worked to gather, analyze, and illustrate data in order to make a case for the Black Belt region as prime siting for Green New Deal initiatives. Organized into five teams, GSD students mapped out opportunities and assets in the Black Belt region, especially as related to production of food and fiber, energy and waste systems, climate resilience, mobility, and access to other resources. The teams also examined regional stakeholders, decision makers, and resource holders in order to gauge the power dynamics at stake in planning out a Green New Deal. With a focus on reparative planning and design, the goal of the seminar was to seek to compensate for and heal past injustices while establishing fair, constructive approaches for forward progress.

Slide from the storymap “Food and Fiber in The Black Belt: A Data Narrative,” featured on the CoDesign Field Lab website. (2)

Dean Sarah M. Whiting to Receive Bevy Leadership Award for Academic Excellence

Sarah M. Whiting, dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture, is the 2021 recipient of the Bevy Leadership Award for Academic Excellence from the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation. The awards program started in 2014 to highlight the work of contemporary women in the fields of architecture, landscape architecture, engineering, development, and construction. A leadership celebration will take place in New York City on October 6, 2021. Whiting joined the Graduate School of Design as dean in 2019, having previously served as dean of Rice University’s School of Architecture. A graduate of Yale, Princeton, and MIT, Whiting is an expert in architectural theory and urbanism. Her research interests include architecture’s relationship with politics, economics, and society and how the built environment shapes the nature of public life. In addition to her roles at the GSD, Whiting is a design principal and cofounder of WW Architecture. Her writing has been published broadly and she is the founding editor of the book series Point. BWAF honorees are selected for the annual awards from names put forth by the foundation’s constituency. “We are interested in scholarship, professional distinction, journalism, corporate achievement, and impact in the advancement of women in the building industry,” according to the BWAF website. Among the other 2021 recipients is Miriam Harris (MUP ’98), executive vice president at Trinity Place Holdings, who will receive the Innovative Executive award.Zero-Waste Architecture for Climate Resilience: Iman S. Fayyad’s CloudHouse Shade Pavilion

In the months that Iman S. Fayyad, lecturer in architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, spent refining the design and construction of the CloudHouse Shade Pavilion, she met many residents and user groups near the proposed site. Greene-Rose Heritage Park, located in one of the most diverse areas of Cambridge, had very little shade before the pavilion was built. Now, Fayyad says, “People have started to feel that they can spend more time there when it’s hot or raining. . . [it’s] a place of refuge.” The pavilion, developed with the City of Cambridge’s Public Space Lab, was designed by Fayyad (MArch ’16) and built with four student researchers: Rayshad Dorsey, Pietro Mendonça, Jack Raymond, and Audrey Watkins (all MArch ’23). It responds to the Resilient Cambridge Plan by providing temporary respite from the heat and rain, and complements longer-term plans for improving tree canopy coverage across the city. Children at the nearby elementary school, who came to see the pavilion’s construction during recess, have returned over the summer with their parents. Teachers and children, emerging from nearby daycares, use the benches for reading sessions. College students playing volleyball take rest breaks underneath the pavilion. A woman who walks her dog by the park told Fayyad about a sudden rain that led nearby residents to shelter under the pavilion and get to know each other. These stories reflect the pavilion’s intention to celebrate existing usage of the park. From the street, CloudHouse frames the park, and is oriented to receive direct daylight in the early morning and evening. During the day, the interior is fully shaded.

View looking North West. Photo: Sam Balukonis

Variation in module geometry creates double oculus in center. Photo: Sam Balukonis