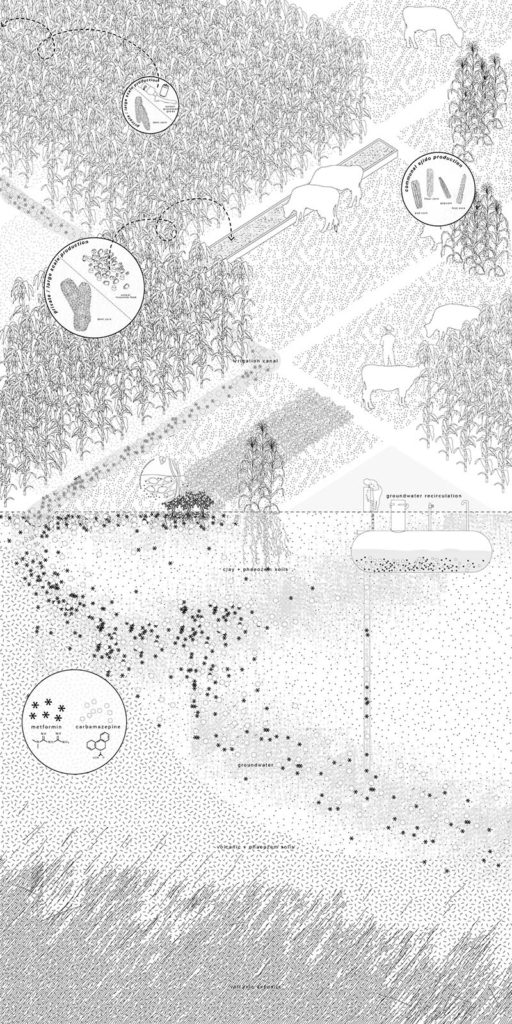

An immense pipe connects Mexico City and the Mezquital Valley. On one side of this 60-kilometer conduit, 20 million people live their lives unaware that each shower, washing cycle, and toilet flush adds to its torrential flow. Every second, 60 thousand liters of raw sewage gushes out of the other end of the pipe and makes its way into the agricultural soil of the arid valley. For more than a hundred years, the nutrient-rich effluent of Mexico City has made the land fertile and productive, despite the smell. Teams of researchers have discovered that the unique volcanic soil of the valley captures organic material, tightly binds heavy metals, and filters biological and chemical toxins from the water—a fortuitous and effective wastewater treatment system.

The balance of city, pipe, and valley seems irreconcilable with contemporary thinking about public health and ecology. Can it be right to dump the mess of an immense metropolis on its hinterlands, to subject a few thousand farmers and laborers to the filth of millions?

But the balance of city, pipe, and valley seems irreconcilable with contemporary thinking about public health and ecology. Can it be right to dump the mess of an immense metropolis on its hinterlands, to subject a few thousand farmers and laborers to the filth of millions? Attitudes have begun to shift, but recent construction of a multibillion-dollar wastewater treatment plant—along with its promises of sanitation, health, and environmental restoration—threatens a delicate balance. Because for all its unpleasantness, the sewage of Mexico City provides huge economic benefits as it delivers nutrients to the farms of the Mezquital Valley. Sending out clean water may seem less offensive to city dwellers, but it offers very little to the farmers, who are already seeing the productivity of their fields decrease.

Recently, three GSD Landscape Architecture faculty won a major prize from the SOM Foundation to study this balance. In their proposal, “The Right to The Sewage: Digesting Mexico City in the Mezquital Valley,” Montserrat Bonvehi-Rosich, Seth Denizen, and David Moreno Mateos will involve GSD students in a multidisciplinary research and design studio “focused on building a holistic understanding of the material connections between the urban and the rural.” Bonvehi-Rosich expresses this goal even more succinctly; she says that the studio will be looking at “both sides of the pipe.” Denizen explains that much of the research on the Mexico City-Mezquital Valley connection has been piecemeal—focused on the sewage treatment problem, the dynamics of soil chemistry, or health issues associated with the use of sewage for agriculture.

The GSD research team and students will broaden perspectives on the situation. Their work will be a call to action to think about “the future of the cycle of water” and to envision “new human/biological relationships” in Mexico City. Always encouraging the students to look at the whole system, Bonvehi-Rosich and Denizen will ask, “How could the city be organized to better prepare its effluence for food production? How could the Mezquital anticipate this?” Students will work with a team of local experts “following the path of water from the moment of extraction in Mexico City until the final stages of the wastewater irrigation system in the fields of Mezquital Valley.” Their goal will be to respond to the system on both sides of the pipe—not merely to deal with wastewater, but to develop strategies and designs that can both change the city and change agriculture in the valley.

The faculty team has already begun orienting students toward the challenges they will encounter when they take on these issues this fall. Bonhevi’s fall 2019 seminar, “The Landscape We Eat,” explored “the relationship between food systems and their geomorphology, climate, infrastructure, time, and culture.” Mateos’s “Ecosystem Restoration” course this semester is studying “biodiversity and ecosystem functionality.” And Denizen’s current seminar, “Thinking through Soil,” is looking specifically at the Mexico City-Mezquital Valley complex to emphasize that “urbanization is always a process of soil formation.” Bonvehi-Rosich and Denizen emphasize that through GSD students’ work in these and other courses, they are well-prepared to address the situation in Mexico broadly—its hydrology, agriculture, and public health—because they are already deeply involved in systems thinking.

While the extraordinary volume of Mexico City’s effluence and the unique soil conditions of the Mezquital Valley frame this project, the challenges of wastewater disposal are global. Denizen points out that “today, three out of four cities in the developing world use untreated wastewater to irrigate agricultural land.” The world is watching what happens in the Mezquital; its success is crucial. Accordingly, Bonvehi-Rosich, Denizen, and Mateos assert that “a basic premise of the studio will be that the world cannot afford for urban wastewater reuse to fail.”